Summary

From the mid-1870s to the early 1890s, Joakim Skovgaard (1856–1933) and a number of other Danish artists set out for Paris to study at the Atelier Bonnat and view the art exhibited in the city. This article aims to promote renewed awareness and appreciation of the impact that Atelier Bonnat’s teachings and the Paris scene had on the artistic development of Danish painters, placing emphasis on some of the first students at Atelier Bonnat, particularly Joakim Skovgaard.

Article

From the mid-1870s to the early 1890s, Danish art saw new developments associated with the artistic advances taking place in France, particularly Paris. Joakim Skovgaard (1856–1933) and a range of other Danish artists set out for the French capital to view the art exhibited there – and, importantly, to study at the private art schools in the city. Several of these artists studied under the same French painter, Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), at his Atelier Bonnat.1While the artists themselves stated that their time in France had a great impact on their evolution as artists, very little research has been conducted on the effect of their training under Bonnat. Indeed, sources regarding this subject are few and far between.2 Drawing on the artists’ own accounts of their times in Paris, this article aims to promote a new understanding of the importance of their training at the Atelier Bonnat and its impact on this special chapter of Danish art history. The article explores the effect of the Danish artists’ time in Paris, placing emphasis on the first pupils at the Atelier Bonnat, especially Skovgaard.

Pandering to French fancies

Up through the 1870s, the young Danish artists had grown increasingly critical of the teaching provided at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. The instruction was characterised by a national focus and a resistance to outside influences. The years 1876–77 saw the launch of a discussion about Danish versus French art when the painter Vilhelm Groth (1842–99) published a brief treatise entitled ‘Dansk Kunst i Forhold til Udlandets’ (Danish Art in relation to Foreign Art)3. At that point he had just returned from Paris, where he spent much of 1872–73 and became preoccupied with the Barbizon School’s new methods of painting, involving broad brushstrokes and spatulas. In reply to Groth’s treatise, the painter Vilhelm Kyhn (1819–1903) published a pamphlet lambasting such ‘pandering to French fancies’4, referring to the use of this new technique that some young painters had picked up, inspired by French role models. Groth in turn wrote a reply to Kyhn, defending the new developments and inspiration from abroad.5Making his retort in 1877, Kyhn continued to advocate upholding a distinctive national feel and style in Danish art, warning against the introduction of foreign ‘dogmas and maxims’ that were not beneficial. Groth defended the artists’ inspiration from France by pointing out how C.W. Eckersberg (1783-1853), widely regarded as the father and foundation of Danish art, had himself gone to Paris and studied under Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). However, Kyhn countered by arguing that Eckersberg did not bring any French influences back with him from Paris to Denmark; rather, Paris caused him to reassert and reinforce his distinctive individual, national traits.6

The 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris became a turning point which truly made the Danish art scene realise that their resistance towards the wider world had to come to an end, and that a little pandering to French fancies offered a way of promoting new developments within Danish art.7 The Danish art exhibition at the Paris world’s fair, orchestrated by Pietro Krohn (1840–1905) presented artists of the Eckersberg school, including several works by P.C. Skovgaard, Wilhelm Marstrand, Godtfred Rump, Christen Dalsgaard and Carl Bloch. It also included a few works by the younger generation, represented here by P.S. Krøyer, Kristian Zahrtmann, Otto Bache and August Jerndorff.8 However, the French art critics had few words of praise for the National Romantic vein of Danish art presented at the show. The acclaimed critic Charles Blanc (1813-1882) stated that Denmark might well have artists, but it had no art. Another critic, Victor Cherbuliez, said: ‘Ce qui distingue surtout les peintres du Danemark, c’est que leur pinceau est toujours propre, il l’est même trop, il est propret, et la nature n’est jamais proprette’.9 Such harsh assessments served to fan the flames of the smouldering critique already being voiced by several of the younger artists, who believed that artists had to open their doors to outside influences in order to reinvigorate domestic traditions with a blast of fresh air.

The older professionals within the field remained unconvinced. In 1879, art historian Julius Lange (1838–96), who had travelled to Paris to see the Exposition Universelle in 1878 and stayed for a few months, gave a lecture at the Kunstforeningen in Copenhagen, headlined ‘Our Art and Art from Abroad’. Here he said,‘The best thing our painters […] could possibly do is to stay at home and not think about anything other than home, preferably forgetting as much as possible that people in other places have a different kind of art, even if that art may be, in many respects, better than their own. […] Rest assured that nothing is held in less esteem in Paris than art which pursues the French ways halfway without ever fully catching up with it’.”10 Lange still believed, then, that Danish artists should stick to their national last and not entertain hopes of winning recognition either at home or in Paris by trying to learn to paint like the French. In 1882, Janus la Cour (1837–1909) included the following statement in a letter to Sigurd Müller; ‘The painter’s own view of nature should decide his way of painting. The Parisian summer coat, with its thick colours and clumsy brushwork, which is now being bought by so many in Paris, is not, to my mind, fit for the weather found in every country’.11 Still, such injunctions fell on stony ground among the younger Danish artists, who only grew even more avidly interested in studying in Paris after 1878.12

The development prompted critique and concern at the academy. One of its professors, Frederik Vermehren (1823–1910, professor 1873–1910), also set out for Paris in 1878 to see the world’s fair. Like Kyhn and Lange, Vermehren championed the value of clearly seeing the national aspects of artists from different countries, urging them to abstain from imitating the national characteristic of others and maintain their own distinctive features.13 While in Paris, Vermehren met with one of the Danish artists who had not stayed home, but instead set out for Paris with the express intention of studying art there, and who was to become Léon Bonnat’s first Danish pupil: Laurits Tuxen (1852–1927). Sigurd Schultz described their meeting in these terms:‘Here half a century’s academic tradition in Denmark met the forerunners of a new age – encountering the emerging competition that was increasingly luring our students away from the Academy, subverting the younger artists’ sympathy for the institution’.14

Forerunners of a new age

The young Danish artists felt that the instruction provided at the Copenhagen art academy was outdated, sensing that new inspiration had to be obtained from schools abroad. Accordingly, Paris became the main destination for young artists wishing to pursue further studies. Some, like Karl Madsen (1855–1938), applied to enrol at the French Academy of Art, but of course this required the ability to speak French.15 The vast majority of Danes instead applied to the various private art schools in Paris, where academically trained painters taught pupils. Many of these schools were based on the academic model from Paris and Copenhagen, but a few took an alternative approach, advocating a different outlook on art. Among these alternative schools, Léon Bonnat’s school was one of the most renowned alongside the schools of Thomas Couture and Charles Gleyre.16 It should be noted that even though the Danish artists believed themselves to be studying under the leading French artists, today neither Bonnat, Couture nor Gleyre are considered among the most pioneering French artists of the time. As Schultz writes, ‘These teachers did not belong among those who would forever stand as trailblazers, the innovators of new developments, but as far as the Danish painters are concerned, they did eventually, in the fullness of time, once again bring the Danes into the fold of European technique’.17 The distinction of being main forerunners now belongs to the Impressionists, whose works were also seen by several of the Danish artists during their time in Paris.

The shift in perception reflects how this period was not only a time of new departures in Danish art, but in French art too. The so-called Salon style of painting with its fine brush strokes and smoothed-out surfaces was challenged first by the Barbizon school with its dark scenes from the forests of Fontainebleau, then by the Realists’ depictions of common workers, depicting people from lower social strata than had hitherto been the norm, and then by the Impressionists’ dissolution of their chosen subject into flickering lights and colours. In France, too, discussions raged: about painting techniques, styles, and what could and could not be accepted at the annual Salon. The Danish artists landed right in the middle of the French debate with the discussions taking place in their native Denmark still ringing at the back of their minds, reflecting the rapid developments seen within the realm of art in both countries.

Although Bonnat is no longer considered a pioneer on the art front today, he nevertheless presented the Danish artists with new techniques of drawing and painting, new styles and a new working method compared to the teachings they knew from home. Sigurd Schultz wrote, ‘This does not mean that Bonnat was singled out for particular pilgrimage. Bonnat came to exert great influence because at that time, he enjoyed a high reputation as a teacher throughout Paris because he himself had contributed to the cause of sophisticated Naturalism […]. Rather, the object of pilgrimage was Paris and French art in general, and many private art schools benefited from the growing numbers of Danish visitors’.18 Bonnat taught the Danish painters about valeur painting, meaning the technique of modulating tones of single colours, and they were affected by the influence from Spanish Baroque art which infused Bonnat’s own works. During the decade in which Laurits Tuxen was the first Danish pupil in 1875 until Vilhelm Tilly (1860–1935) became the eighteenth and final Danish pupil at the Atelier Bonnat in 1885, the French art scene saw major and important new developments. The Danish artists incorporated these changes into their works and brought the new trends back home from Paris.

Who was Léon Bonnat?

Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) was born in Bayonne in the French Basque Country. He trained at a private art school in Paris under the Romantic painter Léon Cogniet (1794–1880) and attended the École des Beaux-Arts for anatomy and perspective classes. As a young man, Bonnat lived in Madrid between 1846 and 1853, where he was inspired by Spanish Baroque masters Diego Velazquez and José de Ribera. Having unsuccessfully competed for French art’s most prestigious award, the Prix de Rome, in 1857, he abandoned the official competitions and established himself as a portrait painter – with great success. He painted a large number of portraits of prominent Frenchmen, including three French presidents.19 While Bonnat was classically trained, the Spanish influence gave his paintings a more realistic feel than the French, academic ideal.

Bonnat practiced what was known as valeur painting, which differed from the academic tonal painting practiced at the École des Beaux-Arts. Tonal painting put particular emphasis on mid-tones, smoothing out all transitions in both shape and colour and making them soft, while valeur painting emphasised the contrast between dark and light tones. Bonnat employed such contrasts in a Baroque-inspired clairobscur manner featuring brightly-lit figures against dark backgrounds. He advocated that, as a painter, one should not lose oneself in individual detail, but make sure that the tonal values, ranging from light to dark, supported the overall effect of the image. This did not mean that one should not paint details, simply that the image should not become subordinate to the details. Bonnat’s practice also differed somewhat from the academic tradition in terms of colour. In order to achieve luminous and saturated colours, Bonnat used a dark background to highlight his figures’ colours. He only mixed his colours loosely on the canvas – a step on the road to the painterly effect that the Impressionists fully embraced in their pictures. But unlike the Impressionists, Bonnat kept to a very limited colour palette.20

In a long letter to art historian Julius Lange, Tuxen described how different Bonnat’s approach to painting was compared to what Tuxen had been taught back home in Copenhagen. He explained the concept of ‘valeur’ in these terms, It simply means that one must shape the entire figure and the whole image with the same care as the individual form […] in other words, if one observes the right values of light, one gives one’s image form and shape; otherwise it becomes flat […] This in turn has a strong impact on the colour; which is driven up to quite a different level of strength […] in practical terms, this is achieved by only blending one’s colours quite loosely, thereby giving rise to the “vibrant” quality; if one does not, the results will be grey and heavy’.21 While valeur painting was not as revolutionary as Impressionism, it nevertheless offered an entirely new and eye-opening approach to painting for the Danish artists studying under Bonnat.

The first Danish pupils of Bonnat

Léon Bonnat opened his private art school, Atelier Bonnat, in 1866.22 As has already been touched upon, Tuxen became the first Danish pupil at Atelier Bonnat in 1875.Tuxen attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen from 1868 to 1872, but Otto Bache (1839-1927) recommended that he study in Paris instead. Having sold his debut painting at the Charlottenborg salon, he spent the proceeds on travelling to the English coast. However, his stay there proved dull, so when he was offered the opportunity of free passage on a freighter docking on the French coast of St. Malo, he crossed the channel and alighted on the shores of France. St. Malo was a favourite resort for Parisians, but also a much-loved haunt for artists. Tuxen met a group of French artists who recommended that he go to Paris. One of these artists, Gaston Renault (1851–1931), was a pupil of Léon Bonnat. He urged Tuxen to apply to study under Alexandre Cabanel (1823–89), a professor at the French Academy of Fine Arts and a recognised representative of the Salon style of painting, and, if no place was available there, then to seek out Bonnat’s school.23 Tuxen heeded the call. He first applied to become a pupil of Cabanel, but when it proved impossible for him to enrol there, he went to Bonnat instead; at the time it was also said that he would probably soon be appointed professor.24

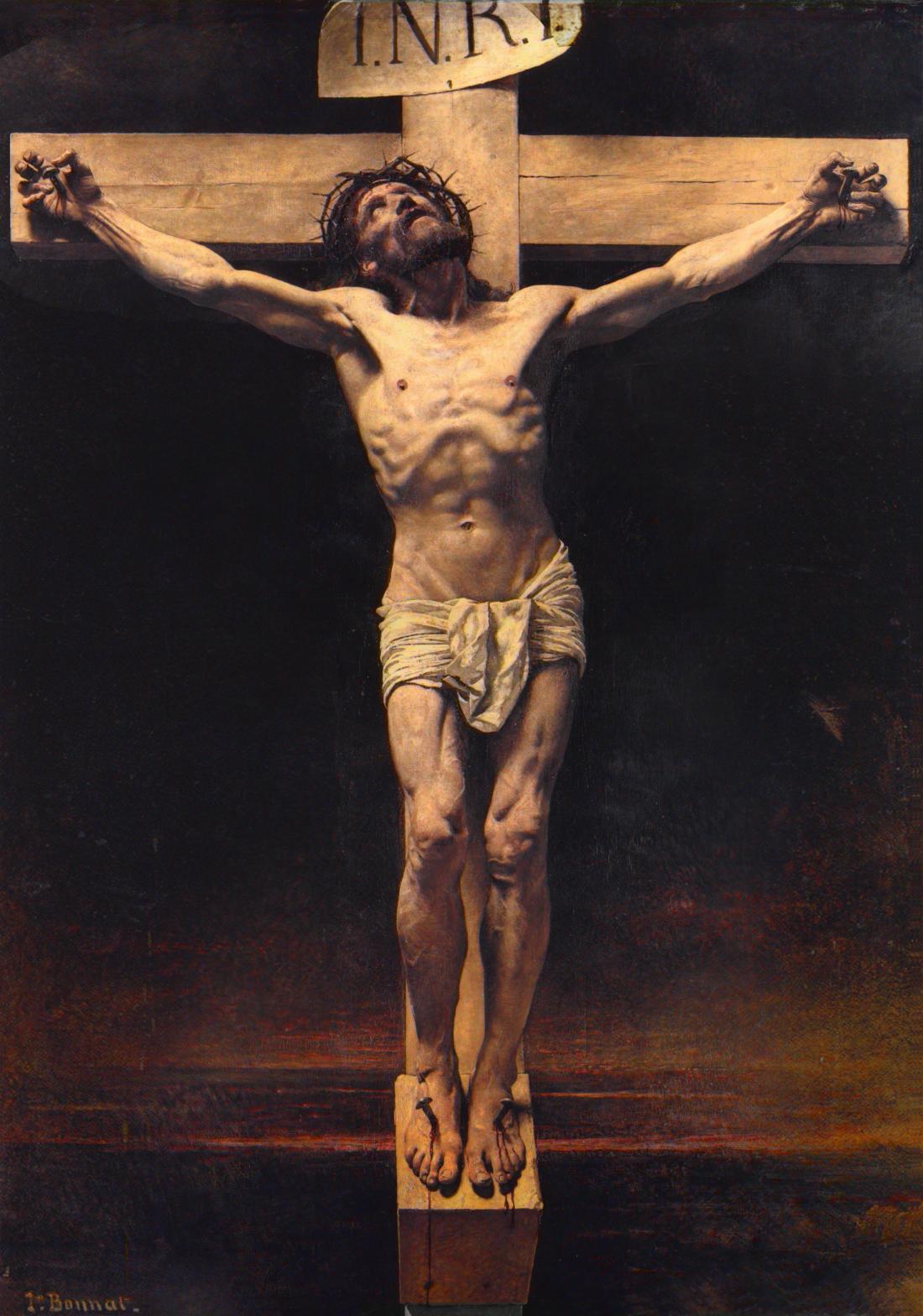

The aforementioned letter from Tuxen to Lange provides a first-hand impression of how Bonnat’s approach to teaching differed from the academy instruction provided in Denmark. Tuxen states,‘What Bonnat demands is a powerful, characterful and true representation of what is before one’s eye; Beauty must come that way, not through any compromise. In so doing you learn to observe nature directly, making you more likely to obtain an independent view of it. By contrast, while I attended the Academy, I would still entertain doubts as to whether the line of that model was good enough as it was, or whether it could be improved’.25 Here, Tuxen emphasises how Bonnat encouraged a realistic approach in his teaching. The model’s appearance was not to be embellished or beautified, the lines of their bodies were not to be improved, but depicted as true to life as possible. Bonnat was known for such direct representation of nature. In fact, one painting he did of Christ crucified [fig. 2] was perceived as so realistic that Bonnat was accused of using a corpse as a model.26

The correspondence of the Danish artists makes it clear that during their studies in Paris they particularly wished to improve their technical skills. The French school was known for its high level and rigorous discipline as regards drawing and painting techniques alike. And technical proficiency was precisely what Bonnat’s second Danish student, Theodor Philipsen (1840–1920), sought during his time there in 1875–76. Philipsen first enrolled in evening classes that focused on drawing, and later went on to take painting classes during the day. In a letter home, he wrote:‘In the evening I draw at a studio run by the skilled portrait painter Bonnat. Tuxen also attends classes there during the day […] I need to develop my drawing and Bonnat keeps good models and corrects us strictly, but is quite pleased with me, yet especially so with Tuxen, he is causing quite a stir with his great progress’.27

Carl Locher (1851–1915) became Bonnat’s third Danish pupil; he too attended classes there in 1875–76 and returned again in 1878 and 1879. Upon his return to Denmark in 1876–77 he met with P.S. Krøyer (1851–1909) and told him of his time in Paris. Krøyer showed Locher his most recent paintings, including a scene from Hornbæk Morning at Hornbæk, the Fishermen Returning (The Hirschsprung Collection, 1875) which had received great praise when exhibited at Charlottenborg in 1876. Locher was, however, critical of Krøyer’s pictures, which he thought ‘thin and insubstantial’ in their manner of painting.28 Shortly afterwards, Krøyer set out for Paris, where he met up with Tuxen, and soon Krøyer too was a pupil of Bonnat. Writing about this, Krøyer said,‘I lack simplicity, grandeur, unity in my light and shadow (“trop des petites choses”, says Bonnat every time). Indeed, I regard this as the main difference between the teachings here and at home, that here one still speaks of simplicity, grandeur, unity, working with the large planes and the great masses of light and shadow; back home, there is a propensity towards getting rather too preoccupied with the individual forms […] I lack much in that regard, and so I believe that I may learn much from attending painting school here’.29

Tuxen and Krøyer in particular have written a great deal about what it was like to be a pupil under Bonnat, how the teaching was conducted and what they learned from their French master; including the things they struggled with. They also wrote home to explain Bonnat’s approach. Krøyer wrote to Mrs Hirschsprung,‘For now, I am speaking specifically of the teaching. When you draw a contour here, the objective is not so much to draw the form in every little fine detail, but first and foremost to capture the totality, the overall line, the proportions and joining of the limbs, the build as a whole, and one may even focus so much on this that one neglects the detail. Which is also, tellingly, reflected in the fact that we only have six times 3 to 4 hours to do each figure. And this is a recurring trait of the whole of his teaching, including when painting: building one’s figure, one’s head in its major planes and proportions, its great masses of light and shadow, and subordinating the detail to the whole, to simplicity, but in doing so great solidity is also required. Next, thickness and light are required of the colour, and all mannerisms, ‘Chic’, sleight of hand is utterly despised’.30 Explaining to family and friends how Bonnat taught them a new way of working with light, plane and form, of working with tonal values, was obviously incumbent on the artists as they sought to justify having taken the almost treacherous step of travelling to Paris to educate themselves. During his second stay with Bonnat, Tuxen wrote, ‘That Krøyer’s art won in fullness and scope during this period of study is beyond dispute, as is the fact that for my part I achieved an understanding of many things that would not have gotten through in my time at the Academy’.31 Bonnat not only taught the young Danish artists valeur painting, which was new and unfamiliar to them; he also showed them a new way of teaching and instructing. In a letter to Vermehren, Krøyer described Bonnat in these terms: ‘he may be the most serious and one of the very best teachers in France; he knows how to truly open his pupils’ eyes and imbue them with energy and zest. […] I have never known any instruction more serious or solid’.32 Bonnat’s gifts as a teacher and his way of teaching and correcting his pupils would have a great impact on the Danish artists.

The teaching at Bonnat

Bonnat’s studio attracted an international crowd of male pupils. Danes were not alone in filling the seats: Swedes, Norwegians, Finns, Americans, Spaniards, even Japanese artists33 flocked to his premises at Boulevard de Clichy, where the teaching was conducted in Tuxen’s, Krøyer’s and Skovgaard’s day. When Joakim Skovgaard enrolled as a pupil of Bonnat in December 1880, he had this to say about his fellow students: ‘By the way, the people studying there are very beautiful, most are Americans, I believe; I think there are around sixty of us all in all (or thereabouts), of which perhaps fifteen are French; at present there are no Germans’.34 Like the other private schools, Bonnat’s studio had a ‘massier’ – a pupil whom Bonnat had entrusted to handle money and practical matters and, if necessary, stand in for Bonnat. The massier received the pupils’ payment for models, rent and firewood.35 While the massier was at the top of the hierarchy, the most recent arrival, ‘le nouveau’, was at the bottom rung of the ladder; one of the newcomer’s duties was to keep the stove fed with coal during winter. In a letter home to his aunt, Skovgaard described his experience of being ‘le nouveau’ and the rituals associated with the position:

‘Well, I attend classes at Bonnat’s. On Monday I made my first entrance in trembling trepidation, for I must tell you that sometimes Le nouveau may be made more of a laughing stock than Le Nouveau would like, and one almost always has to get up on the model’s plinth and sing to the entire assembly, something which I, being such a shy fellow, should not like at all. However, as yet I have gotten off lightly; all I have needed to do is to tend to the stove, meaning that I must feed it coal when it is burning low; today I even had to start over because the fire had gone out, but my friend Didriksen had told the pupils that there was one more nouveau than I (he had arrived two minutes later than me) and so he had to look after the stove for the rest of the day. It is also customary that the nouveau is asked to give ‘bienvenue’, which comes to 20 francs, and if you do not give it, you risk all sorts of things happening. When I went there on my second day, some of the pupils came to me, and one asked me if I understood any French, a little I said, and he asked if I would offer bienvenue, I immediately gave it, and in reply he said that I understood French very well’.36

The teaching consisted exclusively of life classes where pupils would draw or paint after a live model. Painting classes took place during the day, drawing classes at night. Bonnat was by no means present all the time – according to Tuxen he would visit the studio twice a week in the mornings and once a week in the evening.37 Despite the master’s absence, work was done with great intensity and discipline. In a letter to Danish art historian Julius Lange, Tuxen said, You learned to work at a pace unknown in Denmark. […] The four hours of work in the morning were so efficient that the three periods of rest allowed for the model, each of them ten minutes in length, were added to the session, which would thus last from half past seven ‘till noon in the summer, from eight to half past two in winter. Lunch is a hurried affair, taken at a cheap restaurant in the neighbourhood, and in the afternoon hours the pupils would work after their own model until dark. Finally, there was Evening Class from seven to ten. In other words, approx. eleven hours daily’.38 Skovgaard, who attended Bonnat’s school from November 1880 to February 1881, also wrote about his daily routine, which began a little later than Tuxen described it. Nor did Skovgaard attend the evening classes:

‘I get up at a quarter to seven, then have a hot chocolate on my way to the studio, where I arrive around nine; there is quite some way to go, first I must cross the Seine, past the Opera and Bld Clichy, and then a little further yet; I work there until noon, after which I go with Didriksen to eat until one o’clock; then I paint for as long as I can see, upon which I amble homewards again, sometimes I visit Skredsvig, mostly I limit myself to strolling among the shops and getting tempted, but I usually reach home at half past five […] Other than that, now that I attend classes at Bonnat, nothing much happens in my life, one day is very much like the other, I have no time to take in the sights at all’.39

Skovgaard wrote nothing about how Bonnat corrected his work, but Tuxen reported how Bonnat criticised him for not representing the character of the model, getting lost in details instead of keeping the totality of his picture in mind: ‘I remember the first evening he came; “C’est mauvais, pas du tout le caractère du modèle, trop de petites choses – qui est ca”, and looked up at me, standing sheepishly behind him. You must fill in the paper – from here and to there’.40

Another difference between what the Danes had learnt at the Copenhagen academy and what Bonnat taught his pupils concerned the outlines or contours of the figures. Tuxen reported how, ‘According to the directions received back home, I kept the shadow transparent and painted with a dark contour between figure and background. “C’est mauvais, dans la nature il n’y a pas de Contours”’.41 Krøyer too felt the sting of Bonnat’s criticism. Tuxen relates, ‘Krøyer is getting a curing at Bonnat’s studio, much like the one I myself have been subjected to. Bonnat complains about our ingrained frailties, namely a lack of finesse in the colour, as well as a pettiness of form, and Krøyer was much startled one day when Bonnat said that his study looked like a stage set’.42 Initially, Bonnat’s critique might well have seemed harsh to the Danish pupils who arrived in Paris as fully-fledged graduates of their native academy, but his corrections were not just negative. In a letter to his parents written shortly before Christmas 1875, Tuxen states, ‘He [Bonnat] has a strange gift for opening one’s eyes to what is truly at stake in drawing and painting. He corrects in a manner similar to Marstrand, and, like him, he has the ability to make one want to get cracking’.43

Tuxen offered extensive descriptions of the new ways of working he learnt at Bonnat and how they differed from the academic tradition he knew from Denmark. While he had initially had reservations about French art and the French manner of painting, he was gradually convinced that studying in Paris was not hazardous at all, but rather very rewarding. ‘As far as French art is concerned, I have recently taken on a very different view of it than I had before, as indeed I have on painting as a whole. Back home we believe ourselves to be so very honest and true to nature in our representation, but this is as nothing compared to what one is here; the kind of study and imitation of Nature required here we have no inkling of; […] I believe that those who consider it dangerous for young artists to study abroad are much mistaken’.44 Skovgaard, the least loquacious of the three artists, and also the one who spent the shortest period of time studying under Bonnat, wrote, ‘I do not believe that time [with Bonnat] wasted, and in spite of all the evil rumours abounding about this institution, I thrived there’.45

From these descriptions of Tuxen’s, Krøyer’s and Skovgaard’s experiences of the teaching conducted at Bonnat’s, we form the clear impression that the differences in teaching methods and technical approaches came as quite a shock to the Danish artists. Yet we also get the clear impression that scales fell from their eyes at Bonnat’s, revealing to them a whole new way of seeing, drawing and painting, and that their time at Bonnat’s school was extremely instructive for them. However, the Atelier Bonnat was not alone in opening the eyes of Danish artists, making them see art in new ways – they also ventured out to see the art exhibited in Paris.

Looking at art in Paris

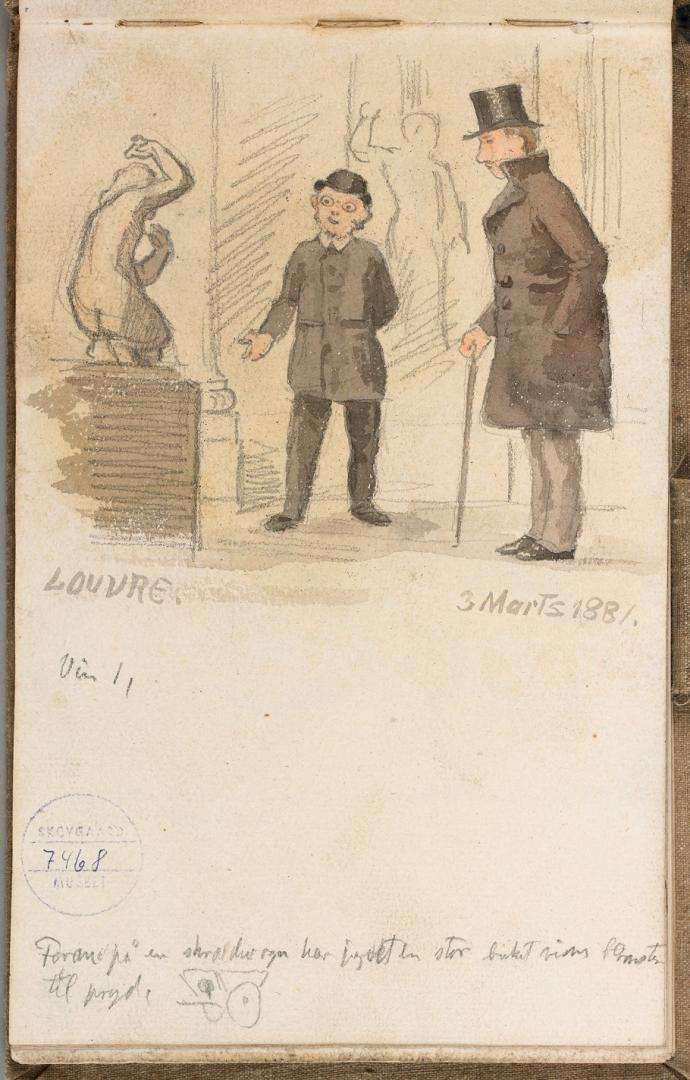

For the Danish artists, part of the attraction of Paris was the opportunities it afforded for viewing the art displayed at the city’s museums, salons, world’s fairs and art dealers. Their interest extended to older as well as newer art. Joakim Skovgaard wrote home to his family, describing several visits to the Louvre alongside with his friend Ludvig Kabell (1853–1902) [fig. 3] and noting the works that particularly captured his attention. In a letter to his aunt Vilhelmine, he wrote:

‘saw Egyptian antiquities, Greek vases and the like, and then some paintings which, at a passing glance, made little impression on me, although there were, by the way, a few Velasques [Velazquez, sic.] which were interesting, but today I have seen better pieces by him. […] we began with Greek sculpture, and it wasn’t long before we saw venus from melos at the end of a long hall, we rushed there and were not disappointed, only I might wish the walls were a little darker in order for her to emerge all the more strongly, (from the front, she stands up against a dark red curtain) and from the left she faces a window which greatly disrupts the effect’.46

To his sister Susette he wrote:

‘From Venus of Melos, which I mentioned in aunt Vilhemine’s letter, we passed through halls of Greek statues up to the paintings, where we soon ended up in the salle carré, where I found myself for the first time in the company of Raphael, Titian, Corregio [Correggio, sic.] and Heaven knows what else. We went on, and in a big room with some old-fashioned trifles we met Amor Hansen [according to Skovgaard a painter of architecture who, despite his name, looked nothing like Cupid], a fortuitous meeting, he put his painting things aside (he is painting a picture from the halls up there) and showed us around among all the delights, o! for Rembrandt’s slaughtered ox, some portraits by Titian, for example the one known as “the man with the glove”; and many things that are better left until I am better acquainted with them. […] Well, back to the Louvre to acquaint ourselves with the French paintings. In order to get to them we had to pass through a department with plenty of ship models and Chinese artefacts, all of which were tremendously amusing, but it was the paintings, yes there were two by Rosseau [Rousseau, sic.], one of them voila, strangely composed, not a lot of nature, perhaps it will grow on me though, nous verrons, yellow flickering air, deep green foreground trees (not so very deep though) the rest with some reddish glow all over; there were also two Delaroches, of which King Edward’s sons interested me greatly. But we had to use our guide too and so we rushed to the Luxembourgh, where I saw Hannoteaux’s frogs, but I shall say more about those to Niels; there was also Coreau [Corot, sic.] or however his name is spelled, I probably got the other names wrong too, and Deaubigny [Daubigny, sic.], but his grape harvest that la Cour has asked me to look at I must take a further look at, not that it isn’t close enough to the eyes, in fact one cannot get a proper distance to look at it, and it needs distance just as much as it needs better light. One thing I believe to have grasped here and that is that the French do not paint quite as I envisioned, they look more like the old Italians and Dutch than I thought’.47

Tuxen related that Bonnat would often send his students to the Louvre to study and copy Rembrandt and Ribera; painters who cultivated the strong contrast between light and darkness, clairobscur, that Bonnat also practiced.48 Tuxen wrote about these visits to the Louvre: ‘Philipsen and I spent some wonderful hours together at the Louvre; feasting on masterpieces of the world from all times, drawing, sculpture, painting; becoming initiated into the highest achievements of mankind. And then, at the same time, working on developing whatever gifts nature may have bestowed upon us. Here was something to strive for’.49 Krøyer too studied the collections at the Louvre, writing to Mrs Hirschsprung, ‘The collections here are wondrous and peerless, and I study them with great pleasure. […] At present, I am copying a picture by Rembrandt at the Louvre’.50

In addition to the older art at the Louvre, there was also the new art on display at the annual Salon exhibition in spring and at the Luxembourg Museum. In a letter to his sister in Denmark, Skovgaard wrote, ‘At the earliest opportunity, I must go to the Luxembourgh, for to me the modern French paintings still form something of a mishmash, or rather a salad of different things, for they are not the same’.51

In a letter to Mrs Hirschsprung, Krøyer described his experience of the Salon,‘When you see the salon for the first time you would hardly think yourself placed within such a solid art school, but the things that are good also derive benefit from this, for example Regnault’s “General Prim” at Luxembourg, Breton’s and Millet’s pictures, etc., etc. But one has to invest oneself somewhat in it all, to properly acquaint oneself with the whole unfamiliar way of working. The first day at the Salon I thought that almost everything there was mere daubs, I thought that everything was topsy-turvy, I felt half sick, but every day I discovered more good things; and I see more and more’.52

Skovgaard and Krøyer appear to have had similar experiences: the large exhibitions, such as the Salon, which could easily accommodate over a thousand paintings, or the Luxembourg, both of them showcasing new French art, were overwhelming and difficult to take in all at once. Viewing and digesting these displays required time. Krøyer wrote home to Professor Vermehren, describing his first impressions of the new French art, which seemed to him unfinished compared to the style he was used to seeing at home:

‘One of the things that first struck me when I arrived in Paris and saw French art was that it wasn’t “finished”. Many of the excellent pictures to which my attention was directed I actually found to be only sketches, in other cases I would find a single thing, admittedly the main subject of the picture – finished to a high degree, with the rest only indicated – I did not understand why the artists did not “finish their work”. – I then came to Bonnat and started working there. There I found the same unfinished quality. Yet at the same time I was amazed to see that they worked far harder and longer to ultimately achieve this – in my opinion – unfinishedness, this sketch-like appearance than I, who almost always finished my work, and often long before the others had reached their goal. I looked at my work, I looked at the others’. I actually thought mine was better, finding the others’ work coarse and rough. Nevertheless, I saw that my studies were grey, flat, without light and, especially, that they quite fell apart when compared to the French, and while theirs stood out clearly in great, simple luminous colours, mine were restless with all their many little colours, their bluish-grey mid-tones, their brown shadows, their predominant lacquer colours. […] But eventually it dawned on me, and I worked with all my might to grasp it. But it was very difficult and now I never “finish”’. 53

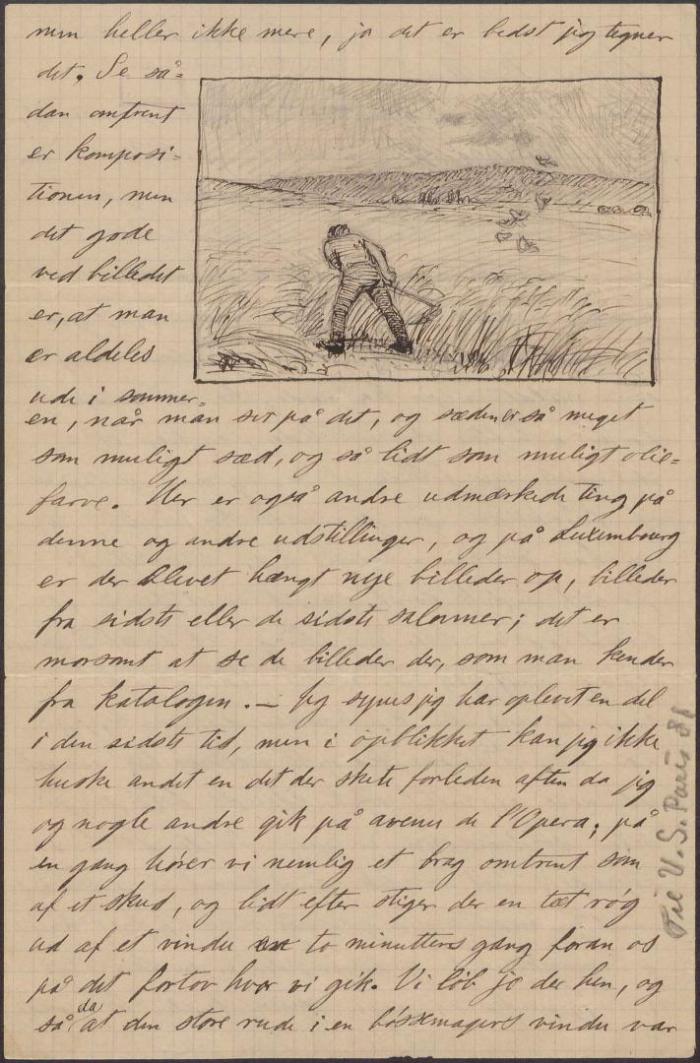

Krøyer learns that this seemingly unfinished character has other qualities, with luminous colours and a sense of unity or coherence connecting the various elements of the composition. Skovgaard also writes about this lack of finish in a painting by Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884) compared to a painting by Jules Breton (1827-1906):

‘There is a picture here in a small exhibition, it is by Bastien Lepage, and I am entirely enchanted by it, it is, to put it briefly, the best painted cornfield I have ever seen. Breton’s ‘blessing of the wheat’ may be a more carefully finished and perfect picture, but the cornfield itself is more perfect in Lepage. It is nothing more than a cornfield with a man mowing it in fine semi-translucent overcast weather, there is a line of woodland in the background and some butterflies in the foreground, but no more, well, it is better that I draw it. [fig. 4] Now, the composition is just about like this, but the excellent thing about the picture is that you are utterly transported out into summer when you look at it, and the corn is as much corn as possible, and as little oil paint as possible. [fig. 5] There are also other excellent things at this and other exhibitions, and at the Luxembourg new pictures have been hung, pictures from the last or previous salons; it is great fun to see the pictures that you know from the catalogues’.54

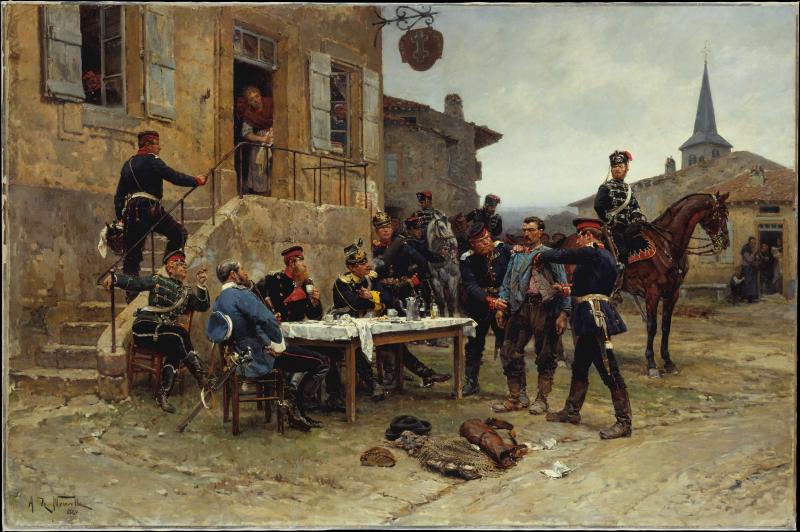

Skovgaard also offered an in-depth description of two battle scenes by Alphonse de Neuville (1836-1885), which he saw at the art dealer Goupil. Both depicted dramatic scenes from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, which France had lost:

‘The other day I went once again to see Goupil’s pictures, there were good things on display that day; what caught my eye the most were two war pictures by Neuville, the one [fig. 6] depicted a French labourer or whatever he happened to be, who had been seized by the Prussians, two soldiers held him and examined his pockets, some officers sat around a table laden with food, the rest of the figures had less to say, even though the French girl looking out of the door was not quite an incidental trifle. But you should have seen how harshly those Prussians were painted, so fiercely and hostilely characterised, while the simple Frenchman cut a noble figure between them. The second picture showed a battle in a city, the French being much overcome, the glints of a few shots dart forth from the windows, but the calm masses of Prussians in the background clearly show that they consider the real fighting over. In the foreground is part of a cemetery that has been occupied by the French, but most of them have fallen or been wounded and lie scattered here and there, a larger heap in front of the gate which they have sought to keep closed against the enemy, but which is being burst apart by the foe, the Prussians crashing in and toppling the few Frenchmen still living onto their dead comrades. In one corner are three or four wounded Frenchmen, they are among the best parts of the picture, especially the youngest, yes, I think I have seen his character every day in the streets, but then this applies to all of them. The reclining wounded are excellent too, one of them lying with a bloody handkerchief covering his nose, I think he might almost be the best and the most terrible all at once. By best, I mean the best characterised, the best painted, you understand. But let us turn to gentler moods. There was a most enchanting little spring scene by Daubigne [Daubigny, sic.], yes, it was that sort of thing, nothing but a path leading up to a house that could be glimpsed behind the trees, and some flowering fruit trees along it, but it was spring, cloudy, humid, all gentleness and verdant lushness. Finally, there was a Millet, painted as clumsily as he could, and then some, but it was a summer’s afternoon and sunshine. The subject was a flock of sheep having descended upon some bushes they encountered on their way, they are rather alike arrayed like that, but there is much of the nature of sheep expressed here; it all brings to mind so vividly what one might come across in the countryside in Denmark on any given day’.55

Generally speaking, the Danish artists had the greatest veneration for painters such as Bastien-Lepage, Breton and Millet, but were less concerned with those painters whose works were even more overwhelming and incomprehensible to the Danes: the Impressionists. Krøyer wrote to Vermehren about the sheer range of expression found within French art:

‘Here we find so many being respected and held in high regard simultaneously: a Puvis de Chavannes, a Henner and a Bastien Lepage, a Daubigny, a Bonnat and a Guillemet: the greatest masters of art, indeed even the Impressionists, a movement that would be nipped in the bud back home if it were allowed to germinate at all, and yet it has exercised a great deal of good influence and even been of major significance even if it does prompt a Danish Heart to outrage, scorn or even faintness’.56

Tuxen and Philipsen also saw the Impressionists during their time in Paris. In his memoirs, Tuxen wrote: ‘Together, we studied an exhibition of this movement [Impressionism], which took place in the Rue Lafayellette; Claude Monet’s experiments with the optical make-up of colour, Sisley’s fresh and fragrant landscapes and Caillebotte’s solid feel for nature. Figures like Degas and Bastien Lepage also took part in the exhibition’.57 In a letter home, Skovgaard stated that, ‘There is an Impressionist exhibition on here now, but I have not seen it yet, I look forward to it, I expect it to be madder than I can even imagine’.58 The Impressionist exhibitions59 took place at a time when several Danish artists studied at Bonnat’s school, but it appears that this particular movement, which was to make such a lasting imprint on art history, was so ‘mad’ in their eyes that they struggled to relate to it. It certainly left very few traces in the artists’ writings from their time in Paris compared to their extensive reports from the Louvre, the Musée du Luxembourg and the Salons.

Creating art in Paris

So what sort of works did Skovgaard and some of the other Danish pupils create while in Paris? The collections at Danish museums house some of the model studies they painted at the school itself [fig. 7 and 8]. Model studies by Krøyer and Skovgaard clearly show how they both employed strong contrasts between light and shadow on the bodies. It is also worth noting how the light serves to sculpt and model the forms of the body, accentuating the plasticity. Here we recognise the artist’s descriptions of Bonnat’s emphasis on light, plane, surface and form.

Bonnat encouraged both Krøyer and Tuxen to paint a classic nude composition to be submitted to the Salon. Tuxen did Susanna and the Elders (1879) [fig. 9]. This is not the version that Tuxen painted for the Salon, but a later repetition of the theme by the artist’s own hand. Krøyer painted Daphnis and Chloé (1878-79) [fig. 10]. Both paintings show the influence of French Salon art in the smooth, naked bodies, the classical poses. Indeed, both pictures were accepted by the Salon, so Tuxen and Krøyer passed the test, proving that they could deliver the style the French wanted to see in their juried exhibition. However, Bonnat concluded that both Danish painters had a greater gift for folk scenes than for nudes.60

Krøyer and Tuxen would both go on to work with open-air folk scenes at the Skagen Colony back in Denmark, but they also painted en plein air on the French west coast. Krøyer had visited St. Malo back in 1877, and in 1879 he set out for Brittany on the Atlantic coast of France, where he painted a number of scenes of local life. He initially stayed in Pont Aven along with a group of artists, and they subsequently travelled out to the coast at Concarneau.61 Here he painted a picture of women working at a sardine curing and packing factory [fig. 11]. Their white bonnets shine out brightly in the dark interior, while a few rays of sunlight find their way inside through openings in the roof and a single window in the background. As in the artist’s nude model pictures, the contrast between light and shadow is very pronounced, and the dark basic tenor testifies to Bonnat’s influence on Krøyer’s work. This painting too was accepted by the Salon, where several critics lavished much praise upon the young Danish painter.62

Skovgaard had painted a scene depicting sheep shearing on Lolland back in 1878, a few years prior to his departure for Paris [fig. 12]. While Skovgaard was in Paris, Heinrich Hirschsprung commissioned another version of the subject. Skovgaard embarked on a new rendition of the scene in the spring of 1881, but under the influence of all the new things he had learned at Bonnat, he changed the picture. The grey clouds in the sky were now painted with looser, wider brushstrokes, while the grass in the foreground has thicker, coarser stalks. Whereas the first edition has a brighter, clearer light, the French version of the painting is permeated by a more obviously overcast feel [fig. 13]. When Skovgaard sent the painting home to Denmark, his brother Niels Skovgaard responded critically, asking his brother this question in a letter, ‘Why do you dance to the tune of the French?’.63 Joakim replied that, ‘The French have many notes in their tunes, and among those some are pure and beautiful, and I should like to dance to them (why else would I be here); mine is but a poor dance, I know, but I hope that I might learn the steps better’.64 However, he also told Hirschsprung that he would change the picture if it failed to please. However, the patron appears to have taken kindly to the painting. In 1895 the two versions of the sheepshearing scene were exhibited alongside one another at Kunstforeningen, prompting Karl Madsen to state that Skovgaard had used ‘banal Paris tricks’ for the 1881 version.65

Regarding the effect of Skovgaard’s time studying under Bonnat in Paris, Schultz wrote, ‘there was a sudden change in Skovgaard’s technique – from the pointed brush and the thin oils to the broad, thick French treatment with undiluted paints straight from the tube and devoid of neat brushwork in the handling. Like other young Danes, Skovgaard also learned to employ hard, rather unnuanced daylight’. 66

When Skovgaard sets out for Italy and Greece in 1883, staying in Greece until 1885, the lessons learnt in Paris suddenly face competition from new impulses, and even shortly after his stay in Paris it can be difficult to discern any immediate traces of Bonnat’s influence in Skovgaard’s art. Still, Schultz nevertheless felt that:

‘As a result of the move towards the monumental and decorative that Joakim Skovgaard pursued, there has been little inclination to study his development in a purely painterly sense, but there can be no doubt that Bonnat’s school had a decisive and liberating impact on him […] It can be traced later in his treatment of the effects of light in interiors with daylight falling in from outside. Likewise, the distinct movement, the one-sided, decoratively excellent expression of movement in his figure studies and his treatment of their form as a single, coherent, plastic mass may perhaps also be traced back to the impulses of Bonnat’s teaching, no matter how independent Skovgaard’s renditions of figures may appear. After all, movement and the unity of form were among the things to which Bonnat sought to open his pupils’ eyes. Joakim Skovgaard and Viggo Pedersen are characteristic examples of the shift in painting methods and techniques that spread rapidly in Danish art around 1880. It eradicated the last remnants of the old craftmanship traditions of painting that had survived at the Academy for a hundred years’.67

Conclusion

Of course, neither Skovgaard’s, Krøyer’s nor Tuxen’s artistic careers can be defined solely by their brief or prolonged stays in Paris and their training at the Atelier Bonnat. But as Karl Madsen wrote in 1888, ‘What Krøyer, Tuxen and the other Parisians taught their fellow artists back home was not technical trickery, but “the great and important matter of making our work more difficult” – […] It is our education, our training towards becoming modern painters that the Parisian travellers have nourished’.68 Indeed, when Skovgaard, Tuxen, Krøyer and the other Danish pupils at Atelier Bonnat set out for Paris, their intention was not simply to learn technical tricks, but to challenge themselves by venturing outside their safe, comfortable surroundings, refusing to simply stick with the accepted wisdom instilled in them by the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts; they wanted to make their work more difficult for themselves by plunging into the deep waters of Paris and learning to swim in an entirely new way, learning a whole new language of art. They brought this new language back to Denmark upon their return, effecting a seminal shift on the Danish art scene. Skovgaard’s share in this transformation is the least well known, partly due to the fact that his time at Bonnat’s school was shorter than Tuxen’s and Krøyer’s, and partly because his correspondence from Paris was aimed at family rather than at professors like Vermehren and patrons like Hirschsprung. Unlike the letters of Krøyer and Tuxen, Skovgaard’s correspondence has not been published before. This article has sought to shed light on Skovgaard’s role as yet another leading Danish artist who sought out Paris and Bonnat, and on the significance this had for his development as an artist during this period.

Appendix: Overview of Danish pupils at Léon Bonnat69

First generation (Atelier Bonnat)

Oct. 1875-summer of 1876, May 1877-Oct. 1878 Laurits Tuxen

Nov. 1875-May 1876 Theodor Philipsen

Nov. 1875-late 1876, 1878-79 Carl Locher

July 1877-82 P.S. Krøyer

1877-78 Bernhard Middelboe

1877-78 Frants Henningsen

1878-79 Hans Nikolaj Hansen

1878-79 Jens Hansen-Aarslev

1879 Christian Zacho

1879-80 Peter Alfred Schou

1879-81 Hans Ole Brasen

1879-81 Joseph Theodor Hansen

1879-80 Carl Rasmussen

1879-80 Niels Wivel

1880-81 Joakim Skovgaard

1880-82 Wilhelm Rosenstand

1881-83 Hans Christian Kofoed

1885 Vilhelm Tilly

Second generation (Atelier de la rue Ampère – Bonnat, Alfred Roll, Puvis)

1887-88 Viggo Pedersen

(Does not attend classes with Bonnat according to Weilbach; only stays in Paris and pont Aven in 1882. Weilbach lists the year as 1881, but the letters in the museum archives date from 1882)

1887-88 Ludvig Kabell

(Is Challons-Lipton mistaken about the dates, or does Kabell return? Weilbach makes no mention of him being a pupil of Bonnat, but according to Joakim Skovgaard’s letters he does study under Bonnat in 1880–81 alongside Skovgaard– meaning that he would have studied at Atelier Bonnat, not at rue Ampère)

Women artists (Académie Trélat – Bonnat, Gérôme, Lepage)

1880-81 Agnes Lunn

1880-81 Bertha Wegmann

Bibliography

Ackermann, Gerald M., ‘Thomas Eakins and his Parisian Masters Gérôme and Bonnat’, in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Tome LXXIII.

Challons-Lipton, Siulolovao, The Scandinavian Pupils of the Atelier Bonnat, 1867-1894, Scandinavian Studies, Volume 6, The Edwin Mellen Press, 2001.

‘Dansk Kunstnerliv i Firserne I-IV’, in Tilskueren 1925, pp. 64-71, 104-09, 348-62, 413-18.

Frederiksen, Finn Termann, Mødested Paris. 1880’ernes avant-garde, Randers Kunstmuseum, 1983.

Groth, Vilhelm, Dansk Kunst i Forhold til Udlandets, København 1876.

Hendriksen, F., En dansk kunstnerkreds fra sidste halvdel af 19. aarhundrede. Bidrag til en Tidsskildring i Breve, Billeder, Oplysninger. Copenhagen 1928.

Bøgh Jensen, Mette; Oelsner, Gertrud (ed.), Tuxen. Farver, friluft og fyrster, Skagens Museum, Fuglsang Kunstmuseum abd Systime, 2014.

Krohn, Mario, Frankrigs og Danmarks Kunstneriske Forbindelse i det 18. Aarhundrede, vols. 1-2, Copenhagen: Henrik Koppels Forlag 1922.

P.S. Krøyer, letters to Frants Henningsen and Bernhard Middelboe, in Kunstbladet 1909, pp. 303–13.

Kyhn, Vilhelm, Dansk Kunst og Kunstudstillingen på Charlottenborg – Nogle Betragtninger af Vilh. Kyhn, Maler. Copenhagen 1876.

Kyhn, Vilhelm, Dansk Kunst. Svar fra V. Kyhn til den ”danske Kunstner”, Copenhagen 1877.

Lange, Julius, Vor Kunst og Udlandets. Copenhagen 1879.

Olsen, Nina Dahlmann, ‘P.C. Skovgaard og hans sønner Joakim og Niels’ relationer til fransk kunst’, in Til og fra Norden. Tyve artikler om nordisk billedkunst og arkitektur, Copenhagen 1999.

Overgaard, Iben (ed.), Joakim Skovgaard, Skovgaard Museet, 2006.

Petersen, Orla, Frans Schwartz, maler og menneske. Odense: Fyns Kunstmuseum, 1990.

Rode, Aksel, Niels Skovgaard, 1943.

Saabye, Marianne, Krøyer – i internationalt lys, Den Hirschsprungske Samling and Skagens Museum, 2011.

Schulz, Sigurd, ‘Danske kunstnere i Paris i tiden mellem restaurationen og den tredje republik’, in Danske i Paris gennem tiderne 1820-1870, vol. 2.1, ed. Franz von Jessen, Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzels Forlag, 1937, pp. 215–336.

Schulz, Sigurd, ‘Danske Kunstnere i Paris under den tredje republik’, in Danske i Paris gennem tiderne 1870-1935, vol. 2.2, ed. Franz von Jessen, Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzels Forlag, 1938, pp. 433–524.

Jørgen Swane and Peter Skovgaard (eds.), Joakim Skovgaards breve til biskop Jørgen Swane og bispinde Magdalene Swane, Viborg 1946.

The Skovgaard Museum letter archives.

Svanholm, Lise, Laurits Tuxen. Europas sidste fyrstemaler, Gyldendal 1990.

Tuxen, Laurits, En Malers Arbejde gennem tredsindstyve Aar, fortalt af ham selv, Copenhagen 1928, pp. 55-84, 237-65.