Summary

The article analyses a series of artistic works whose theme is the norns, a group of goddesses in Norse mythology, seeking to identify a link between this theme and nationalist and political idealisations about Denmark’s mythical past. The research makes use of drawings, etchings and paintings by Johannes Wiedewelt, C.W. Eckersberg, Herman Ernst Freund and J.L. Lund, encompassing a period that extends from 1780-1850.

Articles

My paper investigates the representations of norns in Danish art, choosing a specific historical period extending from the first representation in 1780s until 1850. A few decades later, there was a decline in National Romanticism in the reception of Nordic themes.1 As the main theoretical foundations for the study of images, I rely on studies from the realm of cultural history, especially those of Peter Burke. In such an approach, I seek to understand the fundamental social context in which a particular visual culture was created. Given that the images provide access to contemporary views of a given social world, they then need a series of contexts (cultural, political, material and artistic) in order to be understood.2 As an analysis methodology, I have chosen John Harvey’s considerations about visual culture, about understanding tradition and the intrinsic characteristics of the artefacts, their materiality and their situation.3

As my main theoretical support for the theme of artistic reception I follow the idea that the popularity of Norse mythology in visual arts was due to its connection with ideals of national cultures and the political situation of each Scandinavian country at that time, as defined by Norwegian art historian Knut Ljøgodt.4 The main investigative endeavour is to ponder on the involvement of nationalism in Danish artistic production: in particular, the theme of the norns. How were norns portrayed in Danish art, and how are they related to symbols, themes or motifs linked to ideologies or national sentiments by the Danes?

The norns and the beginning of Nordic reception in Denmark

Norse mythology was an important source of inspiration for several Danish artists. As a direct product of the so-called Nordic Renaissance,5 a great interest in the ancient Norse peoples – their material culture, their sagas and myths – was aroused. The oldest representation of norns in Danish art was executed by Danish sculptor Johannes Wiedewelt (1730–1802) in the 1780s. The norns are a group of supernatural beings with an extremely variable nature depending on the source. Nevertheless, they are also subjected to stereotyped interpretations.6 Wiedewelt’s Norner is part of a set of illustrations made for the opera Balders Død, by the Danish poet Johannes Ewald (1743-1781), based on Saxo Grammaticus’s work Gesta Danorum. It is a direct product of the Nordic Renaissance.7

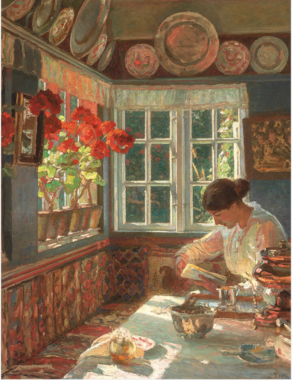

The drawing [Fig. 1] represents the norns Urd, Verdandi and Skuld. The three are in front of a small fountain, in whose waters two swans swim. Urd dips her hand in the waters of a large pot, while Verdandi is supported by a large block of stone and Skuld, turning her back on us, waters the Yggdrasil tree. The details of this scene were directly influenced by Snorri Sturluson’s Edda, which in Wiedewelt’s time was available in French, English and German through the books (1756–70) of Paul Henri Mallet. In the drawing, the only norn whose face we can contemplate is Urd’s (the past); her breasts are also visible. Using allegorical language, Wiedewelt defines the present (Verdandi) and the future (Skuld) as uncertain, while the past remains the true nourishing force for the Danish nation. Especially with Urd’s breasts in plain sight.8

The garb of the norns is based on peasant models, reflecting the artist’s effort to reconstruct a more Nordic reference for the characters of Norse Mythology, distancing himself from the neo-classicist model of moirai and parcai. Even so, Wiedewelt included two vases with Greco-Roman shapes, this being an example of how the Nordic motifs of this period incorporated traditional symbols from the classical tradition to convey the content of the myths.9 From a general point of view, the libretto of the opera Balders Død illustrated here by Wiedewelt was based on the archaeological information available to the artist in his own day: alongside the runic inscriptions, Sámi drums and megaliths, the characters portrayed also bear anachronistic costumes from the Renaissance and Baroque; in addition to this, the image has a certain fantastical and imaginary charge.

The depiction of the norns was part of Wiedewelt’s recent status. In the 1770s, the artist designed Frederik V´s funerary chapel in Roskilde Cathedral, which for him would serve to immortalise the glories of national rulers, in addition to carrying out various works that highlighted the patriotism of the ancient Nordic heroes.10 The adoption of a peasant look for the norns, moving (partly) away from classicist references, gave the characters the customs and traditions of a Denmark closer to their time, thus creating a first reference for a nationalist sentiment which was still taking its first steps in Europe. Within the Danish patriotic conceptions of the eighteenth century, the peasant figure represented something backward; they were considered superstitious and lazy (‘the Others’ within the nation), while the nobility spoke foreign languages and had a cosmopolitan outlook.11 By adopting a peasant look for the norns, Wiedewelt turned things around, anticipating the Romantic nationalist idea that it was among the people (the peasant) that the soul of the nation was truly found: the national character. A few years after this illustration, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) would defend the idea that the traditions, language and clothing of the peasants reflected a cultural continuity from antiquity to the present day and were manifestations of the national character.12

In addition to the garments, a specific detail of the design seems to confirm this conception: the triple knot in Skuld’s hair follows the same pattern constant in images of Valkyries and female supernatural beings, preserved in monuments such as The Hunnestad Monument (DR 284, currently in Lund) and known since the book Monumenta Danica (1643) by the Danish antiquarian Ole Worm (1588–1654). In this regard, the knot formed by the joining of hair above Urd’s naked breasts is also significant, being an allusion to a state of natural freedom and also anticipating the creation of the peasant as a cultural hero by nineteenth-century Scandinavian intellectuals.13

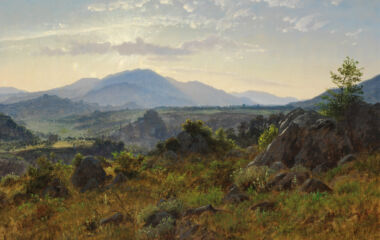

In 1817 norns are once again represented in Danish art, but not as a main or central theme. They appear in the background of the painting Baldr´s death [Fig. 2], by Danish painter C. W. Eckersberg (1783–1853).14 While the main gods appear in the foreground, clad in bright colours and seen under a lot of light, the norns are in the shadows, next to the Yggdrasil tree. They appear in simple and very dark clothes, almost like peasant women, at the outskirts of the events taking place in the foreground, their faces low and sad. Urd points her finger in the direction of Skuld. Verdandi holds a large shield in her hands, ornamented with the sun, moon and two stars.

Eckersberg ended up creating a very personal interpretation of the norns. In the absence of a defined pattern for representing them, he may have known Wiedewelt’s previous drawing and then chosen to depict them in peasant dress. His depictions also moves away from classical tradition in other ways, opting out of any symbolism associated with weaving or differences in age. The detail of the shield associated with the norns does not exist in any medieval or modern literary source.15 Eckersberg inscribes celestial bodies on this object, perhaps to give a more cosmic sense or a cosmic power to these entities, facilitating their role as agents of the destiny (in his interpretation) of the god Balder. At the same time, we perceive some echo of the cosmic and divine power of the norns instituted by N.F.S. Grundtvig in Nordens Mytologi – eller en udsigt over Eddalæren (1808).16

The shield and celestial bodies are also unrelated to Balder’s death as described in the two literary sources used by Eckersberg for his painting: the Prose Edda and Adam Oehlenschläger’s Baldur hin gode (1807).17 Contrary to old interpretations asserting that the painting is predominantly neoclassical, Nora Hansson interpreted it as a classicist only in regards to the formalism of light, its colours and contours, particularly as it also illustrates a blend of equipment and clothing from various historical periods.18 In the painting as a whole, the norns represent the conception that destiny is inevitable, offering no escape. And the detail of the three figures by the Yggdrasil, with mountains in the background, inserts the painting in an effectively mythological landscape.19

The norns in the Copenhagen Mythological contest

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a series of political and social events caused Denmark to undergo a new wave of national sentiment in which mythology became the major theme in the revaluation of the Nordic past. Several writers published various poems and books in which the ancient gods were associated with an idealised outlook on Denmark, the main examples being N.F.S. Grundtvig’s Nordens mytologi (1808) and Nordiske Digte (1807) and Adam Oehlenschläger´s Nordens Guder (1819). The Danish artists strove to create works with a mythological theme, but at the same time several critics questioned the fact that medieval sources did not provide any type of reference or information relevant to their images. In 1801, Oehlenschläger argued that Danish art should use Nordic themes instead of Greek mythology, as they stimulate people’s love for their homeland.20

Between 1812 and 1821 the so-called Mythologie-Striden (The Mythology Dispute) occurred, giving rise to two opposing groups: for or against the Norse theme in Danish art.21 In an 1812 dissertation, the theologian Jens Møller defended the use of ancient Norse themes, stating that it stimulated love for the nation. In the years that followed, these discussions came to occupy The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts,22 and in in 1819 and 1828, Finnur Magnússon was hired as an instructor in mythology and Nordic literature for art students.23 Torkel Baden (secretary of the Academy of Fine Arts) refuted Jens Møller’s ideas, stating that the Nordic themes were deformed and useless, unlike classical mythology, which was sublime, ideal and cultured.24 The painter C. F. Høyer followed the same train of thought, asserting that classical and Christian motifs should prevail in Danish art.25

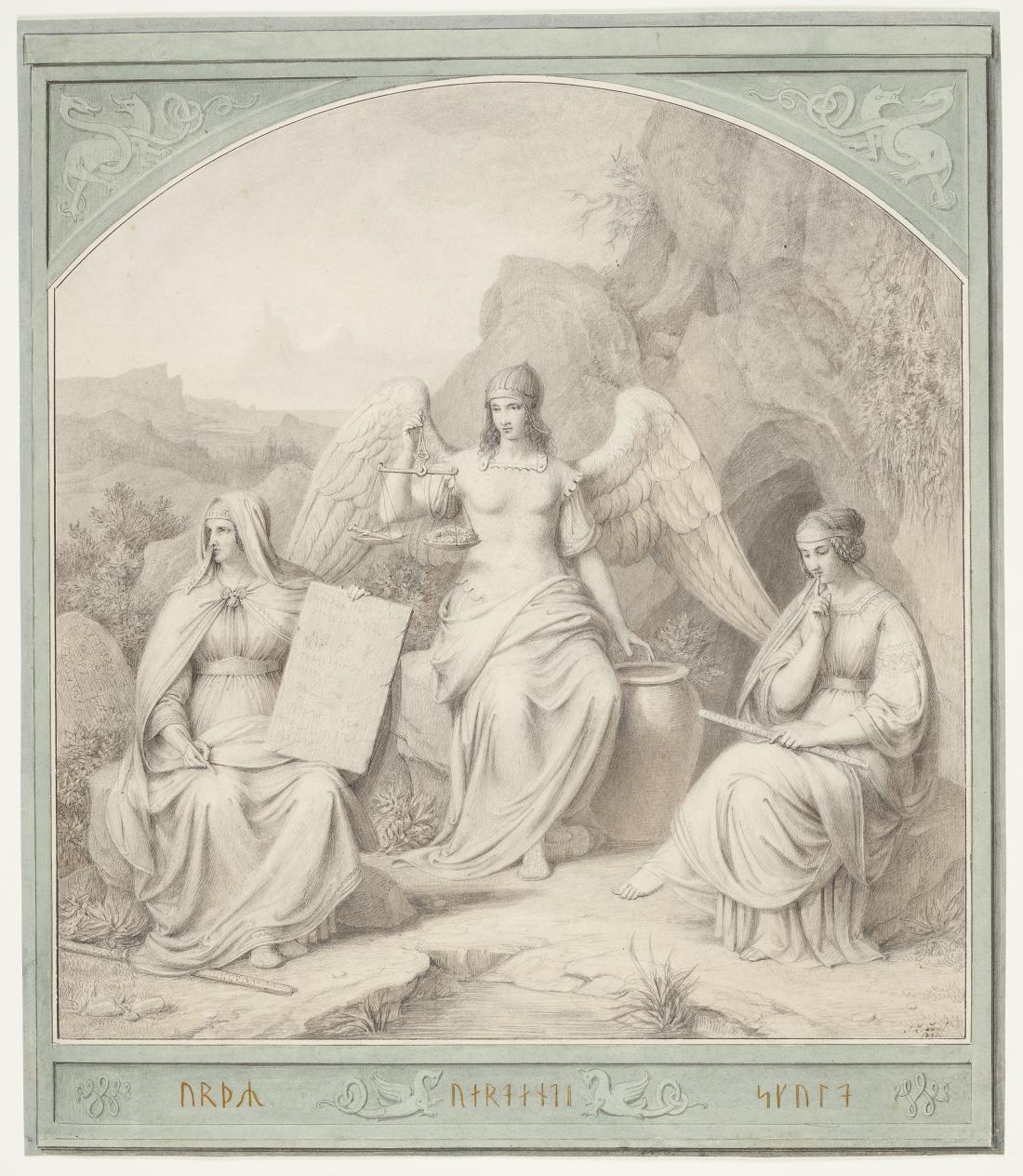

In 1820, Danish prince Christian Frederik asked the eminent sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen to speak publicly in favour of Norse mythology; however, no such thing ever came to happen.26 That same year, the idea of launching an artistic competition with a Nordic theme was fostered and sponsored by Jonas Collin and Johan Bülow.27 An advertisement was published in several Copenhagen newspapers on 21 May 1821 and the contest was promoted by Det skandinaviske Litteraturselskab (Scandinavian Literature Society), remaining open until 1 May 1822. The awards involved sums of money and were divided into three categories: Sketches for paintings; relief compositions, and drawings of individual figures. All proposals were to address themes of Norse mythology and would be judged by Jonas Collin, historian Peter Erasmus Müller, writer Adam Oehlenschläger, architect C. F. Hansen and painters Christian August Lorentzen, C. W. Eckersberg and architect G. F. Hetsch. The winners in the drawings category were J.L. Lund with Balder og Mimer hos nornerne28 (first place) and Andreas Ludvig Koop with Volas spådom (second place), while Hermann Freund received the first prize for his relief (bozetti)29 [Fig. 4], for the same theme as Lund.30

Lund and Freund’s norns share the same structure, despite appearing in different contexts. I have been unable to ascertain who made the first version of the subject or did the original outlines. Even so, we know that the two artists were friends. We suspect that Freund carried out the original design, as he was personally invited by the competition’s patron and even received books from him as inspiration.31 Freund’s award-winning relief is currently at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, while the National Gallery of Denmark keeps the reproduction for this sculpture by Søren Henrik Petersen in 1822 [Fig. 3].

These works feature three sets of characters: a group of valkyries, the norns and two gods, Mimir and Balder. The three valkyries (Gudur, Totha and Skuld) are located on the far left, clad in animal skins and carrying shields and axes. They reflect Germanic patterns with wild and aggressive tones, unlike the other five characters, all markedly classic in nature. Verdandi (Varanda) and Balder are almost completely naked, with hair and features fitting the Greek model. Urd is seated and facing to the left, while Skuld is at the opposite side and Verdandi is standing in the middle of the group. Urd writes on a tablet – matching a description from Vǫluspá, accessible via the Danish translations of the time.32

Verdandi supports one foot on an overturned and overflowing water jar – another idea that may have been taken from Snorri’s Edda and its description of how the norns watered the cosmic tree daily. In turn, the act of the gods Mimir33 and Balder consulting the norns, the detail of Skuld’s wings and her position with her fingers on her lip was taken from Oehlenschläger’s Nordens Guder, published just three years before this image.34 Freund also added wings for Verdandi and, moreover, positioned her in a central and imposing way, including a detail that did not exist in the Edda but appears in Oehlenschläger’s book: a set of scales in her hand.35 This equipment also does not occur in representations of the parcai and moirai in European art. So it is possible that Oehlenschläger and Freund merged two other iconic traditions: the statues of the Nike goddesses of the Greeks with the Lady Justice of the Romans.

Later, in 1826, Freund would include norns in the most ambitious Nordic project in Danish art, the Ragnarök Frieze [Fig. 5] executed for Christiansborg Palace. A part of the panel was installed in 1827. With Freund’s death in 1840, the remainder of the frieze was completed by Hermann Wilhelm Bissen (1798-1868) between 1841 and 1842; however, the ensemble was destroyed by a fire in 1884. The panel now survives only through copies. Freund kept the three Norns in almost the same position and holding the same objects, but they now bore a look more Egyptian than Greek: instead of hair tied or loose, their heads are encircled by bands that fall behind the ears. Despite the changes, the meaning of the motif is perpetuated: Urd is the historical past (the record), Verdandi is the present figured by justice and equity, while Skuld represents the uncertainty of future (previously with her finger on her mouth and looking to the right; now with her chin in her hand and facing left).

The norns in the works of J.L. Lund

A drawing by Lund, Balder og Mimer hos nornerne36 , known from a reproduction [Fig. 6], suggests influences from Freund’s award-winning relief, albeit with modifications.37

Lund leaves only Verdandi with wings, and the scales are passed into Skuld’s hands. Urd is no longer writing, but just holding the sign, this time covered in runes. This time, it is Verdandi who touches her lips with her finger, while Skuld wears armour of the Lorica type – here Lund brings her closer to a homonymous valkyrie, Skuld, a recurring character in the Eddic sources. Overall, the scene is much more Nordic than Freund’s image: the women’s clothing consists of long dresses, capes and brooches, in keeping with ancient Denmark, and Mimir and Balder wear traditional costumes too. The latter has no beard (as in Freund), but rather than Greek hair, he has a face much closer to the face traditionally associated with Christ. Lund used other strategies to bring this landscape closer to the Nordic world. First, he inserted a runestone to the left side of the norns, and two ornate vases to the right. In the background of the scene, on a small slope, is the Yggdrasil tree with the Bifrost rainbow coming out of its crown. At the base of the tree is a megalithic circle of ten stones.

The runestone in the illustration was based on dozens of monuments found throughout Denmark, featured in several antiquarian publications since Ole Worm. One side is covered in serpentining ornaments, while the others bear runic inscriptions. In the early nineteenth century, literature and art still made use of runes according to a Romantic ideal stemming from antiquarian studies, a scenario that began to change after the 1830s.38 In Lund, the runestone and the runes in Urd’s hands serve to reinforce the feeling that the past was rich in wisdom and knowledge, just as the megalithic circle around the cosmic tree reinforces a symbolism of antiquity and unity of the gods.

In 1836. Lund created another depiction of the norns [Fig. 7], this time omitting Mimir and Balder. Virtually the same scene and its elements are preserved (the megaliths, the tree and rainbow, and the runestone), albeit with some small details changed: Skuld is no longer armoured and wears a garland of flowers on her head, making the scene much lighter and more feminine in tone. Her scales carry a dagger and a wreath39, symbolising the balance between war and peace among men in the future.40

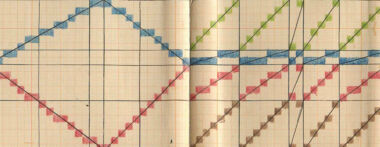

Lund continues to explore the theme of norns in a study from 1842 [Fig. 8] and in the painting De tre norner from 1844 [Fig. 9]. Both share the same structure, differing only in the use of colours and some minor details.41 The painting has painted side frames, depicting beasts and snakes on the upper part (a common motif in rune stones) as well as the name of the three norns written in Danish-style runes (the younger futhark).42 Each female character boasts a strong and vibrant colour (purple, red and green), all contrasting with each other. Such contrast is characteristic of the Nazarene movement with which Lund was associated, referring to the patterns of the Italian Renaissance.43 Here all parts of the image were executed with precision and balance of the elements. There is no difference between nature and the three female beings; all have a strong symbolic charge: the fountain in the foreground, the cave44 on the left and the Yggdrasil tree to the right.

The norn Urd is in front of a cave, here symbolising the past. Conveying a very determined attitude, she is the only one with a vigorous look. Verdandi is in front of the fountain, symbolising the actions that can be judged in the present (by the scales), while Skuld remains seated with Yggdrasil behind her silhouette. Here the cosmic tree takes on cosmic significance related to the future. Compared to his 1822 drawing [fig. 6], here the harmony and natural balance of the three norns imbues the painting with a much greater sense of time and destiny.

In this painting, Lund has chosen to hybridise his previous illustrations by incorporating certain elements from Hermann Freund’s relief: Urd writing on the blackboard; Verdandi with wings and carrying scales; Skuld holding a staff. Between one norn and another, he inserted an ornamented vase. One of the transformations involved placing Verdandi in the central position, almost upright and carrying the scales: these had already been inserted in the works of by Freund and Lund in 1822 and now once again become the main focal point of the image. Lund preserves the runic wooden staff, but here it is almost shaped like a sword,45 perhaps an allusion to the valkyrie Skuld. The order of the norns was inspired by the conception of time and age, with Urd presented with a veil and cape (the oldest), Verdandi with braids and a spiral diadem (middle age) and Skuld, the youngest, with a diadem and simpler braids. As for the general meaning of the painting, scholar Anna Schram Vejlby has observed that its figures exhibit far more symbolic than realistic attitudes, their gestures and gaze communicating a sense of reflection and eternity.46

The Destiny of a Nation

A central question remains: Why were the norns chosen as a central theme in Freund and Lund’s two award-winning works? The first answer may lie in Oehlenschläger’s book. While in the Eddas the norns appear as shadowy figures, in quick and fragmented descriptions, in Nordens Guder they became an important part of the XIV canto (Iduns Frelse), being connected not only with the liberation of Idunn, but with the fate of all the gods and the universe. Oehlenschläger was inspired by Snorri Sturluson’s quick comment that in the Urd fountain the gods met in council, turning the norns into advisors to characters such as the valkyries (included by Freund in his relief), as well as Bragi, Mimir and Balder. Nordens Guder was a product of Danish Romanticism, in which the Nordic characters had Homeric characteristics and languages.47 Thus, the classicist filtering of the norns is not only a choice of the sculptor, but a reception (Freund) of the reception (Oehlenschläger) of Norse myths.

But the question is still, why – among so many gods and mythical scenes in Oehlenschläger’s book Nordens Guder – did Freund and Lund choose norns as the central theme?48 I have to once again emphasise that until that moment the norns had never before been main motifs in works of art and it is with the Copenhagen contest that they gain notoriety.49 Out of a total of thirty chapters in Oehlenschläger’s book, thirteen deal directly with the god Thor – the most important deity in the artistic reception of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; Loki appears in five cantos titles; Odin is quoted in almost every corner.

The scene of the three norns gathered to receive the gods Mimir and Balder becomes an allegory of Danish national culture for both Freund and Lund [Fig. 4 and Fig. 6]. With Denmark going through territorial problems and international conflicts, in addition to recent economic troubles, the socio-political context of this time sought to find ways of overcoming such troubles and also of building identities for the new moment. While Oehlenschläger saw mythical times as a heroic model,50 Freund and Lund chose the norns as a model based on their power over time – they regulated men; the gods bowed to them, making them true symbols of destiny.51 Nothing could be better suited to representing a mythical past for the country at that time.

On the left side of Freund’s relief [Fig. 4], imposing, heavily armed valkyries symbolise death, battle and victory, following the standards in force in Romantic art.52 They also became personifications of war, especially poignant in the context of the military humiliations suffered during and after the Napoleonic wars. Accordingly, they become nationalist allegories in the early nineteenth century.53 Freund’s three valkyries were initially inspired by Snorri Sturluson (Gudur, Rotha, Skuld) but featured much more Germanic elements (bear pelts) than the mail-clad warriors in the Sandberg painting Valkyrior ridande till strid, 1820, commissioned by Sweden King Karl XIV Johan. Along with this more militarised aspect, Mimir and Balder reinforce the other ideal notions about the nation.54 Mimir represents wisdom – he carries a vase, representing his connection to the roots of Yggdrasil. And Balder represents Christ and the new religion in the Nordic world.55 Thus, in Freund’s relief, the norns balance a mythical time poised between political-military power and religious wisdom, indispensable for a model of nationalist identity in the first half of the nineteenth century.

In this context, art served as a propagator of myths that contained significant symbols for the political context,56 but in order to understand the significance of norns in Danish art, we first have to understand the multiple variations prevalent in the notions of nationality and nationalism at this time. For Denmark, there were three main contexts: patriotism, literary nationalism and political nationalism, in addition to a tolerant form (nationality) and a more aggressive one (nationalism).57 In the 1820s, several of these positions bled into each other. After the Battle of Copenhagen (1807) and the loss of Norway (1814), artists and writers sought an identity for the nation, based on a historical, mythical and literary past. Ancient Norse myths were an ideal solution, especially after the Nordic Renaissance, providing models of behaviour, virtue and ideals for the new nation’s project and its inhabitants. While these myths served a pan-Scandinavian purpose, they were used with regional intentions, as we can see in the preface to the translation of the Poetic Edda by Magnussen in 1821:

Thus, we get know the true national spirit on which our life and existence is founded – and then we realise that the three main peoples, generally called Nordic (Danish, Swedish and Norwegian) were originally brothers, spoke the same language and shared the same faith (…) As such, they belong to the older Danish language (…) Our oldest literary memorial I, as the reader will be aware, the so-called elder Edda, insofar as it contains the oldest national poems and legends of our people (…)58

In this context, the mythological competition of 1822, inspired by prince Christian Frederik and sponsored by Jonas Collin, united the artistic and political intentions associated with the idealisation of the nation’s mythical past. And the two main prize winners, both depicting the theme of norns, were inspired by Oehlenschläger’s perception of these female beings controlling the fate of gods and men. Thus, norns became the ideal embodiment of a mythical identity for Denmark: they incorporated a symbolism from the past, a celebration of the present and hope and triumph for the future. The norns were the subject of the main relief of the Ragnarök frieze and, just like Lund’s collection of historical religious paintings, were executed for the Christiansborg palace under the initial sponsorship of Frederik VI in 1827. This king’s government was authoritarian and reactionary, abandoning the liberal ideas of his time as a prince. The new reform of the Christiansborg Palace, completed in 1828, maintained a government policy based on the existing order of society and an ideological wish to base the future nation on its past.59 To put it in other words: a country with a national culture based on ancient myths and history.

Conclusion

Norns, like Norse myths in general, were rediscovered by Danish art in the late eighteenth century. Concerning the written sources that underpin the art, the earlier pictures (by the artists Wiedewelt, Eckersberg, Lund and Freund) draw heavily on Vǫluspá (stanzas 19–20) as well as Snorri’s Edda version. Representations of norns were very closely associated with the notions of culture and identity prevalent at the time and their aesthetic variation was a direct product of the lack of a standardised iconography of myths, allowing room for interpretations and artistic license on the part of the artists. Such representations were also given further impetus by writers like Oehlenschläger and Grundtvig and their nationalist interpretations of medieval sources and canonical patterns followed by European art regarding moirai and parcai. Just as medieval myths were themselves quite flexible,60 their reception in modern art varied a great deal, too.

The norns are just a small facet of Norse reception in Danish art. Other themes have been much more frequently portrayed, such as Odin, Thor, the valkyries, the goddesses Freja and Frigg, Ragnarök, among others. We are still waiting for more detailed studies regarding Norse deities, as well as for an analysis that is able to compare and contrast Denmark’s artistic production with that of other Scandinavian countries during the nineteenth century, especially Sweden and Norway. We hope this article can contribute to such interest, helping to unveil that past, which is deeply interconnected with art, myth and history.

I am grateful to Karen Bek-Pedersen for reading the original text and sending her valuable suggestions; Anna Schram, William R. Rix, Lise P. Andersen, Rikke L. Christensen, Thomas Lederballe, Camilla Cadell, Per Larsson, Benedikte Brincker and Nora Hansson for sending information and bibliographies; Vitor Menini, Victor Sampaio and Pablo Miranda for revising the text.