Summary

Hans Smidth (1839–1917) rarely dated his paintings, and the present article examines the specific challenge this poses for a subsequent dating of his art. The objective is partly to create a more secure basis for the assessment of Smidth’s artistic development, but also to add greater nuance to the hitherto rather one-sided narrative describing Smidth as an introverted artist who was little affected by external influences. The lack of dates has contributed to anchoring the mystery associated with Smidth’s position in Danish art.

Articles

‘Hans Smidth’s art was a peculiar blend of the old-fashioned and the modern, of tradition and personality’.1 Johannes E. Hohlenberg’s (1881–1960) eulogy to the artist Hans Ludvig Smidth (1839-1917), who passed away on 5 May 1917, was just one of many that sought to briefly outline the artist’s place and significance in Danish art. Hohlenberg’s words can be said to sum up the challenge faced by the scholars of posterity struggling to pinpoint Smidth’s place within Danish art history. Smidth enjoyed recognition in his own day, but in art history he nevertheless remained a ‘peculiar blend’ of several of the artistic movements dominant during his lifetime. He created his art during times of change and turmoil where the echoes of National Romanticism still reverberated even as new, modern modes of expression struck new chords. What is more, Smidth only rarely dated his works, which may have added to the difficulties in identifying his position in Danish art history.

Smidth has not previously been the subject of scholarly research, and in-depth material about the artist is scarce – especially if one wants information of a recent date. The most important separate treatments of Smidth are Jørgen Sthyr’s (1905–1978) Malerier af Hans Smidth from 1933 and Hans Edvard Nørregård-Nielsen’s (b. 1945) Hans Smidth 1839–1917, which was published in 1989. Smidth is featured in several of the major reference works about the period’s art in Denmark, but this material serves only to shore up the narrative about an artist who has been difficult to place within art history and its definitions of styles and periods. He is described as a ‘solitary figure […] in his life and in his art’2, as an artist who ‘went his own way’3 and as a ‘loner’4 to mention just a few examples that describe the artist as standing outside of an established art history framework. Even during Smidth’s own lifetime, in 1915, Carl V. Petersen describes him as ‘one of the quietest and most subdued of characters; known personally only by very few, even among his fellow artists’,5 opointing out that Smidth’s worth and importance in Danish painting ‘is as yet far from fully understood and asserted’.6 One of the aspects that have not been fully addressed before concerns the processes of exchange that took place between Smidth and his own time. This mutual relationship has only rarely been accorded any importance, being largely overlooked in favour of a narrative about an artist who worked alone and did not draw inspiration from others. Investigating this issue in relation to the article’s focus on dating seems obviously relevant, as the widespread perception of Smidth as a loner is partly linked to the lack of a proper overview of his development as an artist, which is why Smidth is often interpreted as being out of step with his own time.

Methodological reflections on chronological homelessness and the problem of chronology

Smidth is richly represented in Danish museum collections, which own approximately 254 works by him.7 This should be compared up against the fact that the artist is believed to have produced approximately 1,000 works in total.8 While he signed almost everything he did, he only rarely dated his works. The challenge of dating Smidth’s art has been pointed out for many years now, and indeed Nørregård-Nielsen notes that ‘a chronology would not pin down Smidth’s paintings as if they were butterflies, but it would establish an overview that would more clearly show what Smidth was capable of, what he wanted, and what he actually achieved’.9 The objective of this article is to explore the possibilities of establishing a chrolonology of Smidth’s works and, in doing so, to investigate how the issue of chronology can contribute to a broader understanding of Smidth. It will also involve methodological considerations concerning the dating of his undated material. This will be addressed through a biographical and chronological review of Smidth’s life and development as an artist, as exemplified through various works of art, including two of Museum Salling’s undated paintings by Smidth [figs. 8, 28]. A chronology will create a better starting point for establishing his position in relation to his own day and will contribute to a more nuanced image of him as an artist.

Only very few paintings by Smidth can be dated with certainty, with the year of their creation entered on the work itself. In museum records, many of the other, undated paintings have had to settle for very wide date brackets, often extending across all of the artist’s active years from approximately 1860 to 1917. Hence, using the works where the dating is certain as chronological pointers in a timeline of the artist’s work would seem an obvious choice. However, this approach can do no more than to create a tentative overview of Smidth’s artistic development, sources of inspiration and choice of subject matter.

The exhibition catalogues from the annual juried salons at Charlottenborg, where Smidth exhibited from 1867 to 1917, can further assist in dating some of the artist’s works. Although only very few of the exhibition catalogues state the dimensions of the works, the titles can in some cases be helpful. From here on in, the work becomes more difficult as we venture into increasingly unknown territories; even early scholars such as Sthyr address the problems inherent in seeking to date Smidth’s work on the basis of the artist’s working methods, not least because Smidth would reuse older sketches and subjects: ‘This approach, combined with the fact that his drawings are almost never dated, makes an accurate chronological classification impossible’.10 However, Sthyr also goes on to say that it is possible to identify certain groupings within the oeuvre that can help establish a dating of the works. Similarly, Knud Voss (1929–1991) notes that Smidth’s technique and brushstrokes can help date his works as his brushstrokes become looser and his application of paint grows increasingly pastose as the years go by.11 One of the challenges with this kind of stylistic analysis of Smidth’s works is that it may appear to be infused by a teleological interpretation where his development is seen to be consistent with an overall movement from a traditional mode of expression to a modern, Impressionistic style. However, as I will demonstrate in this article, Smidth’s evolution does not seem to be solely and consistently progressive in nature, which renders attempts to establish a linear chronology more difficult: Smidth repeatedly returned to the same subjects throughout his life.

Art in times of change and turmoil

Hans Smidth was fifteen years old when, in 1854, he moved from Kerteminde to Skive with his family, a move prompted by the fact that his father, Edvard Philip Smidth (1807–1878), had been made town and county bailiff there the year before. This relocation is described as a ‘journey that sealed his fate’12 in Carl V. Petersen’s (1868–1938) biography from 1915, which is based on interviews with Smidth. Even though the young Smidth did not seem to evince any particular interest in art at that time, the landscapes of Jutland, its people and customs, the extensive Alheden moors with its expanses of heather would all win a prominent place in his art a few years later. Having graduated from Viborg Katedralskole in 1858, Smidth set out for Copenhagen to study medicine alongside his older brother. His brief stint as a medical student would prove very important in relation to Smidth’s incipient interest in art, as he would draw sketches of some of the patients during his shifts at Frederiks Hospital. What is more, a fellow student at medical school introduced Smidth to his younger brother, Theodor Philipsen (1840–1920). This happened around the time when, in 1861, Smidth decided to abandon his medical training and apply for admission to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts instead. Smidth’s decision was crucially important in prompting the young Philipsen, who was studying agriculture at the time, to do the same. Among other things, the two budding artists spent five weeks of the summer of 1862 with the Smidth family in Skive.

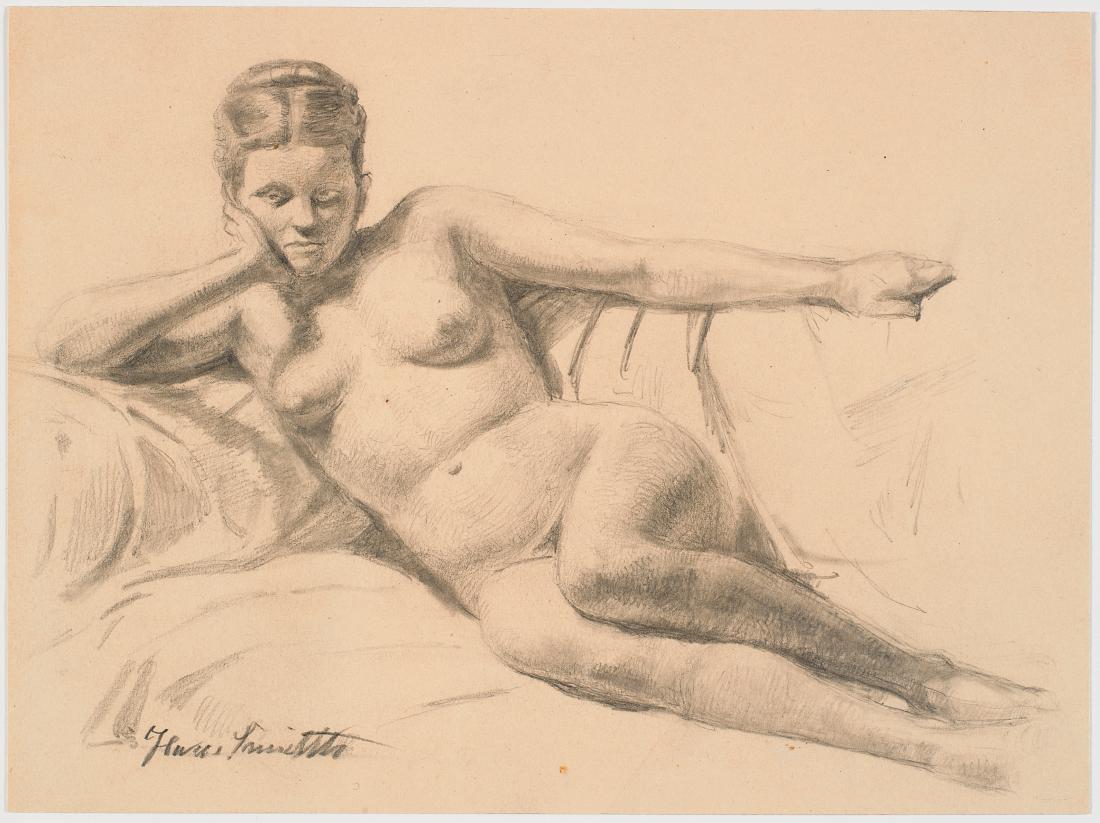

At the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Smidth was taught by several of the pre-eminent artists of the day who had their roots in the so-called Golden Age13 of Danish art, including Niels Simonsen (1807–85), Wilhelm Marstrand (1810–73) and Jørgen Roed (1808–88). The Royal Collection of Graphic Art contains some model studies of nudes presumably done during Smidth’s time at the Academy’s model school in 1864, testifying to his classical schooling. [fig.1] Besides Philipsen, Smidth’s fellow students include Edvard Petersen (1841–1911), and they all attended the Academy during a period characterised by a break away from the traditional structures imposed on art since the Golden Age, a framework which was now the subject of a gradual revolt.14

After 1850 period, Danish art saw an increasing focus on folk scenes, genre painting and moralising tales, all of which were based on an outlook on Danish national art advocated by the influential art historian Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870). However, two groups wanted to pursue different directions, causing a clash between two camps. On one side stood the so-called ‘Høyenians’, also known as ‘The Blonde Ones’, who supported Høyen and a national-liberal political point of departure. On the other side were ‘the Europeans’, also known as ‘The Brown Ones’, a designation used for those artists who were in opposition to Høyen and adopted an international outlook, embracing artistic expressions from outside.15 Nørregård-Nielsen proclaims Smidth to be a ‘confused observer’16 in the battle between the two groupings, a position which does not appear to represent a deliberate choice on the part of the artist. Several artists of the day did not necessarily allow themselves to be defined by this grouping, but have been pigeonholed by art historians of posterity; however, this does not seem to apply to Smidth. In terms of form and subject matter alike, Smidth’s aesthetic has a kinship with the national vein of art, where folk scenes and landscapes are among the favourite themes, but the moralising and idealising narratives about Denmark and nationhood generally associated with the style do not appear in Smidth. What is more, throughout his career Smidth exhibited an open-minded approach to new modes of expressions and subjects generally associated with the so-called ‘Europeans’. When considering Smidth’s art in the contexts of the two groupings, it cannot be conclusively assigned to either camp, a fact which has rendered Smidth’s position difficult to pin down within an art history that has been greatly infused by this particular division. Hence, Smidth has been allocated to the interesting, albeit diffuse, category of ‘loners’.

On his own. Back in Skive

In the years 1864–65, Smidth did military service alongside his friend and fellow artist Philipsen, but whereas Philipsen took part in the Battle of Sankelmark and left the army having attained the rank of lieutenant, Smidth never saw war and was sent home as a sub-corporal. This less-than-illustrious military career was followed by several unfortunate events for Smidth. In 1866, he had to abandon his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts and return to his parents in Skive; the family was in financial difficulties and his elder brother had died of tuberculosis.

This is to say that Smidth returned to Skive without having completed any degree, neither medicine nor art, and having no glorious stories of war to tell. After returning home, he would set out on solitary walks with his paintbox, affording him ample opportunities to immerse himself in his art on his own. The walks took him far and wide in Salling, to Fur and Fjend Herred but also out to the lime mines in Daugbjerg and Mønsted, the Karup Å river and further out towards the Alheden moors and the Herning region. Later in his long life he also travelled further north towards Himmerland, Vendsyssel, and after the family got a holiday cottage at Ry, this area too entered his sketchbooks and canvases. His fascination with the fjord, the great stretches of heathland and the lives of the common folk gave him enough subjects to last him a lifetime.

The four or five years that Smidth spent at the art academy provided him with valuable artistic foundations, but he still struggled with issues of technique and his choice of subject matter. Among the early works done soon after leaving the academy, we find some interior scenes, a theme that would continue to occupy him throughout his life. The painting Interor. Fjends Shire [fig.2] from the Hirschsprung Collection is an excellent example of how Smidth was primarily influenced by the Danish movement of National Romantic painting in his young years. Echoes of the artists Frederik Vermehren (1823–1910) and in particular Christen Dalsgaard (1924–1907) are clearly evident; the latter shared the same geographical starting point as Smidth, namely Skive. Dalsgaard, who was born and raised on the estate of Krabbesholm, enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1841, so it is doubtful that the two artists ever got to know each other. Even so, there is something to be gained by comparing and contrasting the two artists, who in many ways addressed similar subject matter in their portrayals of everyday life in Jutland. Dalsgaard is widely considered one of the most important representatives of Danish National Romantic genre painting and was a great supporter of Høyen. Narrative content is a foundational element of Dalsgaard’s paintings, often emphasised by long and descriptive titles that underpin the emotional and tragic tales. [fig.3]

Smidth’s painting of the living room from Fjends Shire has the same level of detail, meticulous execution and colour scheme that characterises Dalsgaard. What is more, national symbols have a prominent place in Smidt’s composition, too. However, certain differences are well worth noting as well. Dalsgaard’s picturesque details take their point of departure in anecdotal narratives, in the peasants, their clothing and, not least, in psychological characterisation.17 Smidth, on the other hand, tends more towards taking his starting point in the formal qualities of the subject, such as the room, the light and the colours. The painting of the Fjends interior shows how, right from an early point of his career, Smidth let the paintings speak for themselves as paintings rather than as narratives. The woman in the painting is positioned quite undramatically inside the room. Even though she has been portrayed in some detail, she nevertheless appears to be of secondary importance: the light flowing in through some unseen window in the workshop beyond is imbued with greater vibrancy and life than the woman. The secondary nature of the woman is borne out by closer study of how her headgear was painted. Here we find obvious pentimento, revealing that Smidth did not intend the woman to have this pose in the original composition.

Along with a growing interest in and cultivation of light, the passage of years also saw the introduction of freer brushstrokes that are not found in the paintings from the early years back in the 1860s. The painting of the living room is among the rare fully-finished works from the period that have been painted on canvas. After the artist’s return to Skive, the majority of his works were painted on cardboard sized with glue as he could not afford canvas. Thus, the choice of support helps us date the artist’s earlier works. However, this is also the reason why early works by the artist’s hand are rare; the glue used to treat the cardboard eventually caused it to crack, making the subject simply crumble away.18 Nevertheless, the lightweight, inexpensive materials had the advantage of enabling the artist to go on long walks, painting studies right in front of his chosen subject matter – such as the small work on cardboard known as At Skive Fjord. View towards Staarup [fig.4], which can also be reasonably presumed to date from the 1860s.

Folk scenes and a calm attentiveness

In 1867, Smidth had two of his paintings accepted for display at the annual juried Charlottenborg exhibition; he went on to exhibit there every year until his death in 1917. The annual exhibition appears to form a mainstay in his work, increasing his motivation to create new works and improve his artistic skill. He is taught by Vilhelm Kyhn (1819–1903) in 1870–71 at the so-called ‘Cave Academy’ (Huleakademi) alongside a range of other young artists that included Harald Foss (1843–1922), Godfred Christensen (1845–1928), Vilhelm Groth (1842–1899) and Anton Thiele (1838–1902). Around this time he begins to spend his winters in Copenhagen, but continues to paint and live in the Skive region in summer. However, Smidth struggles with his own insecurities in the company of fellow artists; in 1875 he writes a letter to Edvard Petersen, describing how is he seized by a sense of ‘[…] dejection prompted by my less fortunate works and the resulting anxiety about presenting myself as an artist […] There is this lack of confidence and boldness that has always bothered me when out in society’.19 Despite his insecurities, Smidth decides to take part in a competition in 1875, specifically for the Neuhauen Award. The assignment set for the participants was ‘Driving Home the Geese’. In a letter to Petersen dated October 1874, Smidth describes working with geese as his subject:

I am now resolved on how I want the goose painting to look […] I am working hard on the geese; I have had one in the garden for some time and am considering getting some more […] but o! they are difficult creatures to manage.20

Smidth did not win the main prize for his goose painting, but still managed to win extra commendation and reward for his work. What is more, he created a wealth of sketches and studies of geese that secured this bird a place in Smidth’s painting throughout the rest of his career. Geese are among the many motifs revived in 1879, specifically in the paintings Flocks of Geese being Herded through Ry [fig.5] as well as Landscape with Geese, Cows and Milk Churns [fig.28], which will be addressed later in this article.

One may reasonably presume that from this point on, Smidth relied exclusively on his sketches of geese made during this period, or that he continued to draw after stuffed models. However, the story goes that his stuffed specimens were in such poor condition that they spoiled, went rotten and gave him typhus.21

In 1877 he once again took part in the competition for the Neuhausen Award; this time the assignment was for ‘A Folk Scene’. In another letter to Petersen he once again expresses his concerns about working with figure painting as he had ‘neglected figures in favour of making some mediocre landscape studies’.22 Even so, we may assume that this work was instrumental in prompting him to carry out several figure studies in Jutland and Funen; subject which, like the geese, are revisited in several paintings in subsequent years. The folk scene A Stranger Asking for Directions at a Moorland Farm [fig.6] from 1877 wins Smidth the Neuhausen Award. Even though the artist does inject a greater sense of dynamism and movement into his paintings in the 1870s, the award-winning painting can come across as somewhat rigid in structure and dry in its colour scheme. Smidth’s portrayals of the distinctive people of Jutland, and not least their habitat, depict an era that is coming to a close. The moorland farm seen in the painting is Glattrup Gård from Skive, which was even at that time a farm that had been passed down through generations. The style of the painting has been compared to works the National Romantics Dalsgaard, Roed and Jørgen Sonne (1801–1890).23

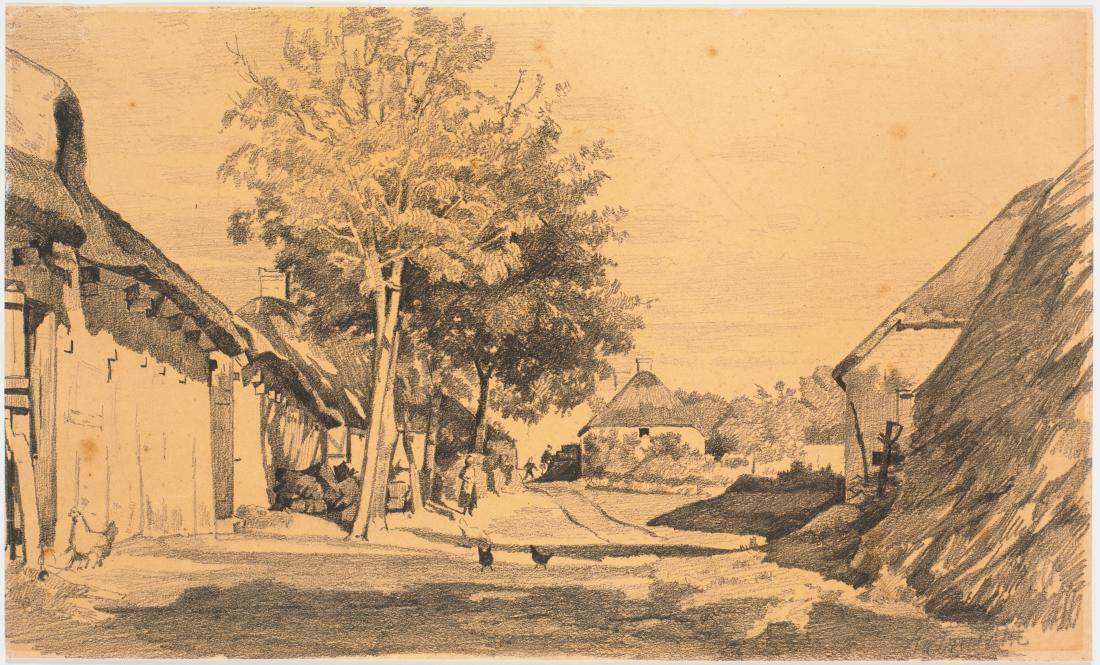

he narrative in Smidth’s painting is clear and made even more explicit in a – for him – unusually descriptive title: we see the stranger on horseback getting directions from the farmer pointing with the tip of his pipe. The painting’s composition seems to be a kind of template for other paintings of his, such as the depiction of geese being herded through Ry [fig.5]; there are certain similarities in the placing of the horizon line and the location and heft of the buildings. In addition, Smidth uses a special approach to perspective, one which is repeated in several of his paintings during this period as well as in subsequent works: a road winding its way into the picture. The distinctive thing about this approach is that Smidth places himself, and thus the viewer, in the middle of the road and in the centre of the scenario, just as is the case in other paintings such as the scene with the geese, the drawing Village Road in Sunlight [fig.7] and the painting Peasants in their Sunday Best on their way Home from Church [fig.8]. The latter painting also brings to mind the older National Romantics, Roed, Dalsgaard and Sonne, with their almost ethnographic portrayal of the lives of common folk, capturing a time that was fast disappearing.

Dating Peasants in their Sunday Best on their way Home from Church

The painting Peasants in their Sunday Best on their way Home from Church [fig.8] is among the many undated paintings by Smidth. However, several factors suggest that the painting can be dated to the late 1870s. During this period the artist had a special interest in folk scenes and figure studies, as described above. What is more, the title of the painting has a certain kinship with a title stated in the catalogue of the annual Forårsudstilling (Spring Salon) at Charlottenborg in 1878: En Søndag-Eftermiddag i Efteraaret. Folk gaae fra Kirke. Motivet fra Vestjylland – meaning Sunday Afternoon, Autumn. People Returning Home from Church. A West Jutland Scene.

The Charlottenborg exhibitions were popular and an important place to see the very latest art. The 1878 spring salon was visited by Anna Brøndum, who would go on to become Anna Ancher (1859–1935), prompting her to write an enthusiastic account to her cousin Martha in a letter describing how this particular painting by Smidth had made an impression on her:

[…] then there is a truly excellent painting by Smi[d]th, you know the one, I believe he won the award last year; it is Peasants Walking Home from Church, they look like people from up where Uncle Martin used to live, at Torslev, and they are such excellently depicted peasants, their dress and their characters are so accurate and true; o! I should like to own that.24

There is much to suggest that the young Anna Ancher’s enthusiasm about the painting found expression in more than just a letter. Later that same year she herself paints a painting of an older married couple from Skagen on their way home from church. [fig.9] It also turns out that Anna Ancher’s dream of owning the painting she described would come partially true later: the collection at Michael og Anna Ancher’s house in Skagen includes five paintings by Smidth, one of which is a figure study of a Woman Heading Home from Church. [fig.10]

The figure in this small painting has a striking resemblance to one of the women clad in in green in the larger painting of peasants returning from church, although her headgear has been changed from a scarf to a more sophisticated hat. Something similar applies in Seven Figure Studies Mounted on Canvas [fig.11], dated at around the 1870s, from the Hirschsprung Collection, where the study of the woman in the blue-black dress also appears in the large painting. The figure study of the man in the top hat appears in reverse in the background of the large painting, and the figure study of the young, short-haired girl in the long dress might conceivably be the girl found in the painting A Stranger Asking his Way at a Farm on the Moors. [fig.6] Based on this, it seems reasonable to set the date of the creation of Peasants in their Sunday Best on their way Home from Church at circa 1878. The appearance of the figures depicted also bears out such a dating. The sideburns and distinctive beards seen in the painting are in keeping with 1870s fashions, and the top hat was the most popular hat type at the time. The women’s dress and silhouette are also typical of the period, opting for a fuller profile all the way around the body rather than just at the rear as had previously been the fashion.25 We should however, still be aware of the caveat that dating a painting solely on the basis of the peasant’s dress and hairstyles would not necessarily be accurate given that Smidth would often return to old sketches and figure studies several years after he originally did them.

The painting Peasants in their Sunday Best on their way Home from Church can also be regarded as a key to a hitherto unexplored relationship between Smidth and the Anchers.

In his 1937 book Jydske Folkelivsmalere (Folk Scene Painters of Jutland, 1937), Johannes V. Jensen (1873–1950) notes that Smidth’s portrait is nowhere to be found in the Brøndum Dining Room in Skagen, even though it boasts a very extensive array of painters of the generation.26 However, there is nothing to suggest that Smidth went all the way up to Denmark’s northernmost point to paint; it is more likely that their relationship is rooted in Amalievej on Frederiksberg, where Smidth and the Anchers both spent the winter months from the 1890s onwards; he in no. 3, they in no. 6.27 This may explain how Anna Ancher had the opportunity to acquire paintings by the artist who had so fascinated her as a young woman.

Another point of connection between Smidth and Anna Ancher also merits attention here: they share the common trait of both having had close ties to their chosen subject matter and the environments they portrayed. They knew them well from the inside. Ancher, the only Skagen painter to have been born and raised in Skagen, had a special relationship with and in-depth knowledge of the local people, the countryside and daily life.28 Similarly, Smidth was not a merely a spectator to the lives of the peasants of the heather-clad moors, nor did he observe them from a distance as exotic creatures. On his walks he stayed with the peasants and took part in their Spartan lives, lodging in the farmhand’s chambers and sharing their meals. Despite being described as a quiet and introverted person, he nevertheless won the confidence of the peasants. It is likely that his useful knowledge from his years at medical school was a point in his favour in social interactions among a rural population living far away from any doctors. Smidth painted the people as they were, eschewing any anecdotal stories so that his portrayals never devolved into ‘tourist sentimentality’ or ‘mawkish depictions of life among the common folk’, as Haavard Rostrup (1907–1986) concludes.29

‘Art at First Hand’ – an eye for real life

The sense of a genuine connection with his subject matter is a characteristic feature of Smidth’s work, and one can observe how this empathy only grew even more acute as the years went by and the artist’s realistic style matured. We cannot know whether Smidth deliberately adhered to Herman Bang’s (1857–1912) advice from his 1879 manifesto ‘Realisme og Realister’ (Realism and Realists), but the writer’s description is a very apt match for the artist’s approach to his circle of subject matter:

One must observe life […] One must know the society one wished to depict as well as a botanist knows the district in which he lives and moves […] And to obtain such familiarity, the writer must step out into the throng.30

In the same section, Bang pointed out that reality is ‘far richer’ than the imagination, thereby eloquently expressing the Realist movement’s relationship with verisimilitude and issuing a call to get involved in life.

Realism is, alongside Naturalism and Impressionism, the dominant movements in late nineteenth-century art. All three styles share a focus on personal, first-hand experience. Following the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, where Denmark’s contribution of National Romantic artists from the Høyen circle came across as hopelessly old-fashioned among the French Impressionists, Julius Lange (1838–1896) put the new outlook on art into words in 1879:

What we require is this: Art experienced at first hand, expressions of what has been personally seen and felt; we demand realness in art and will not settle for dead masks whose only claim to justification is that they supposedly depict something Great and Good.31

Lange replaced his former professor, Høyen, as the most influential art historian in Denmark. Indeed, the idea of art ‘at first hand’ can be traced back to an injunction made by Høyen in 1844, urging artists to ‘familiarise themselves with the lives of the common folk in their comings and goings’.32 Whereas Høyen advocated the choice of specifically national subject matter, Lange turned his direction to the evolution of art in a European perspective. Narrow conceptions about ‘king and country’ receded in favour of a reality infused by new political and social conditions, paving the way for new subjects and new modes of artistic expression.

There is a general problem with the definition of Realism and Naturalism, as the terms are often used synonymously. Both styles depict reality without imposing any romanticising layers. But whereas Realism strives for a depiction of reality based in a particular attitude or message, Naturalism aims for a more objective imitation of nature.33 This also gives Naturalism a greater kinship with the immediacy of Impressionism. Smidth’s paintings contain elements of all three directions. Smidth is most often described in connection with the Realist movement in Danish art – for example, Hornung does so in his 1993 book on Realism, but he also notes that: ‘One might hesitate to call Hans Smidth a Realist at all were it not for the fact that he portrayed the rural common folk of Jutland in as down-to-earth and direct manner as [L.A.] Ring depicted their Zealand counterparts’.34 Nørregård-Nielsen does, however, dwell particularly on Smidth’s reserved, subjective approach: ‘Hans Smidth painted what he saw; I am not saying that he did so without emotion, far from it, but his paintings contain neither any elegy for what is fading away, nor any rejection of the coming thing’.35 The diffuse relationship between the subjective and the objective in Smidth’s art contributes to the difficulty in pinpointing and pigeonholing his style. The commitment and involvement evident in his depictions of Jutland landscapes, peasants, poor people, gypsies and people from other strata of society is an important factor governing why he has primarily been associated with Realism.

Exploring new subjects

Smidth’s new outlook on reality becomes particularly prominent in the late 1880s.36 In 1887 Smidth paints one of his more daring and distinctive works, Travellers in a Third-Class Compartment [fig.12]. The painting has a sketch-like feel, yet is both signed and dated. The brushwork is a marked contrast to his early works from the 1860s, which were more detailed and fully finished. The choice of subject matter testifies to Smidth’s awareness of the more modern world, but also to his penchant for the depiction of individual characters. Several scholars have compared the piece to the French artist Honoré Daumier’s (1808–79) painting on the same subject from circa 1862–64 [fig.13].37 To Smidth, the idea of going abroad held little allure,38 and we do not know whether he was aware of Daumier and his art. Even so, the similarities are worth mentioning as French art appears to have influenced Smidth’s works in the late 1880s.

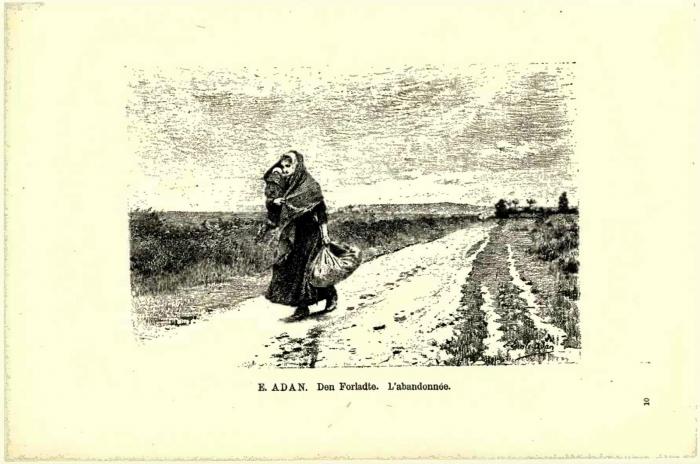

It seems reasonable to assume that Smidth was made familiar with such new art through fellow artists and friends Philipsen and Petersen, who drew inspiration from a trip abroad to France in 1875: Philipsen was particularly fascinated with Impressionism, while Petersen found inspiration in French Realism for his depictions of street life in the city. Also noteworthy in this connection is ‘The French Art Exhibition’ held in Copenhagen in 1888, a show that particularly presented Realist art. While no reports exist to conclusively ascertain whether Schmidt ever saw this exhibition, there is a kinship between one of his paintings and Louis-Émile Adan’s (1839-1937) L’abandonnée, which was on display at the Danish exhibition and is illustrated in the exhibition catalogue [fig.14].

Smidth’s undated painting Traveller Carrying her Child , [fig.15] depicts a woman in more or less the same pose and wearing clothes of the same kind as the figure in Adan’s work. With this painting, Schmidt portraits a person from a rung of society that had hitherto not been a popular motif in Danish art.

A similarly barren landscape and long, empty path also appears in in Smidth’s 1913 painting, School Children on the Moors [fig.16], which also shares a compositional kinship with Adan’s painting. While we have no documentation proving that Smidth saw the French exhibition, it is very likely that he saw the exhibition catalogue and its illustration of Adan’s painting. Smidth’s undated painting of the ‘gypsy’/traveller woman can be estimated to have been painted just after 1888 or in the 1890s, where Smidth was particularly interested in this subject. At the time, gypsies – in Danish ‘Taterne’, a term used partly for the nomadic Roma people, partly for ‘Travellers’, often denoting (transient) beggars and workers within less palatable field such as night soil men, knackers, etc. – were considered a radical choice of subject matter in art.

Yet once again, we find that a firm dating based on the choice of subject is rendered difficult: Schmidt returns to the gypsy/‘Tater’ theme in a paining exhibited at the 1915 Charlottenborg exhibition; it is listed under the title Natmandsbryllup. Kæpkastning (A Wedding among Travellers. Throwing Sticks). The painting The Glazier on the Heath [fig.17], dated at around 1890, also portrays a ‘Traveller’. The composition, the human figure and their gaze, the moors and the dog in the right-hand side might also testify to inspiration from Vermehren’s A Jutland Shepherd on the Moors [fig.18]. The definition of ‘Tatere’ in Denmark remains rather unclair. Some believe the term to apply to itinerant peoples from abroad such as the Roma, while others also included indigenous Danes of no fixed abode – ‘Travellers’, also known as ‘rascals’. It seems likely that Smidth identifies easily with such wandering outsiders, and indeed his depictions of ‘Tater’ people convey no sense of reserve or aloofness.

Smidth projects a similar sense of empathy and identification when creating illustrations for the well-known Danish writer Steen Steensen Blicher’s (1782–1848) short stories in the 1890s. Blicher wandered the Jutland moors generations prior to Smidth, so in many ways the artist was ideally suited to heed Blicher’s call for a ‘Dutch brush’ to depict ‘this dismal scene’39 in Pennekas Draller’s Gypsy Dance from 1894. [fig.19]

Smidth’s portrayals are described as being ‘just as genuinely Jutlandish in Body and Soul as Blicher’s text required’.40 Smidth is believed to have acquired what Blicher called a ‘Dutch brush’ by drawing inspiration from the Dutch painter Aert van der Neer (1603–77), specifically from his dark images of moonlit landscapes and of fires in towns and villages at night. Smidth would have been able to see such paintings at The Royal Collection of Paintings in Copenhagen. [fig.20] It would appear that Smidth also referred to this source of inspiration in his later paintings of fires, a motif to which he returned repeatedly from 1910 until his death. Here the artist’s interest in colours and light find expression in new ways through dark colours and a strong chiaroscuro effect. The painting A Farm on Fire [fig.21] conveys a strong sense of the hardships of life as the peasants sit in their bullock cart, quietly observing a ferocious fire lighting up the dark sky.

When working on the illustrations for Blicher’s short stories, Smidth must have come across Blicher’s description of the moors as a difficult subject with its wide, empty vistas where ‘there is no raised thing to serve as a landmark’.41 Up until this point, the moors have acted as the backdrop of Smidth’s Jutland scenes, but in the 1890s he accepts the challenge of depicting the moors themselves in all their simplicity. [fig.22] In many ways, this is a daring and complicated choice of subject matter, and one in which Smidth successfully demonstrates the merit and value of undramatic, quiet painting at an early stage in Danish art. The calm serenity resting over these landscapes where light and colours come together to form a totality42 has echoes of the stillness found in Smidth’s paintings of interiors. His observations of his chosen subject matter not only testify to a close and intimate relationship with his surroundings, but also to an interestingly down-to-earth approach that makes even his rare imaginary motifs seem believable, like scenes experienced at first hand.

Complex figure compositions: Slave wars and market scenes

Smidth’s moorland landscapes can be very simple, but he was able to match their simplicity with an equal complexity in other compositions. In many ways, the 1890s saw Smidth working with more challenging subjects, ranging from the aforementioned ‘Travellers’ and Blicher’s short stories to the Jutland Slave Wars and market scenes. For an artist who usually let himself be inspired by his own day and age and by everyday life in the country, picking up on historical subjects from decades ago is hardly an obvious choice. Nevertheless, several paintings from around 1894–95 see Smidth selecting ‘The Jutland Slave War’ as subject matter for dramatic scenes, for example in A Lookout Post. [fig.23]

The Jutland Slave War took place in 1848, except that it was not in fact a war, but rather what one might term ‘fake news’, to use a contemporary phrase. It involved a rapidly spreading story claiming that prisoners escaping from hard labour had broken out of Rendsborg and were marauding up through Jutland, causing peasants to band together out of fear, brandishing home-made weapons. In fact, however, there were no escaping slaves, so one may reasonably assume that Smidth indulged a humorous aspect to his nature with these dramatic and tragic-comic scenes. Even so, one senses the peasants’ grim seriousness in the paintings. Hornung notes that Smidth’s take on history painting and his choice of the ‘Slave War’ motif is a ‘suitably quietly and uneventful theme for Hans Smidth’.43 As far as Smidth was concerned, his main motivation for painting this motif may have rested on a fascination with figure studies and with the peasant’s costume and uniform, giving the work the feel of a genre painting.

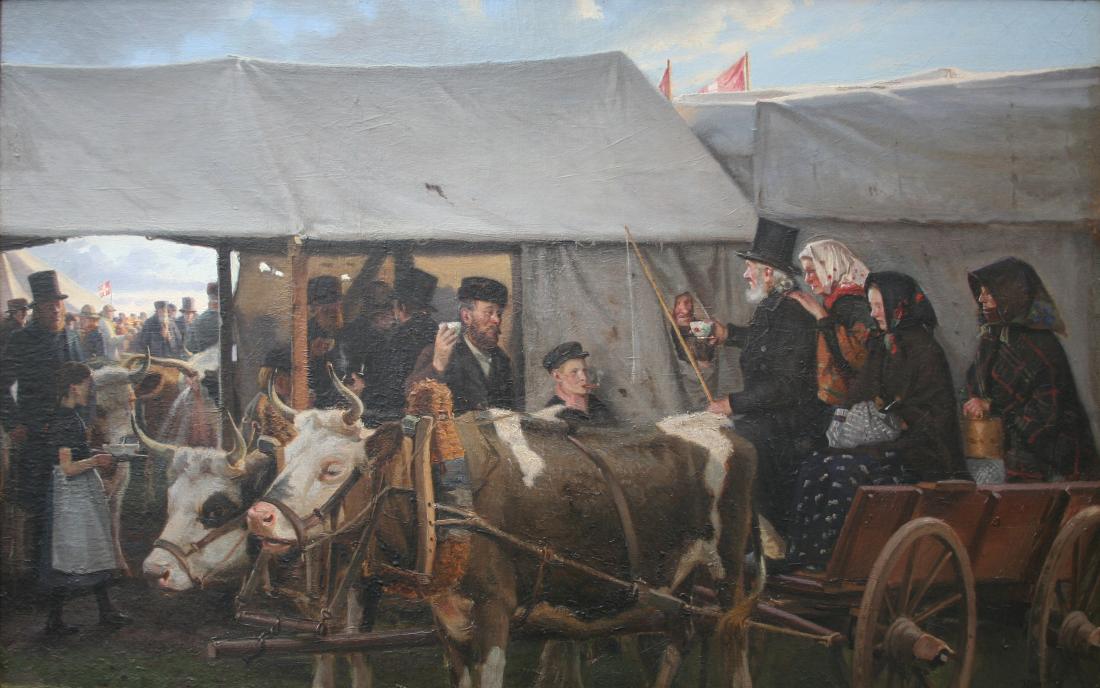

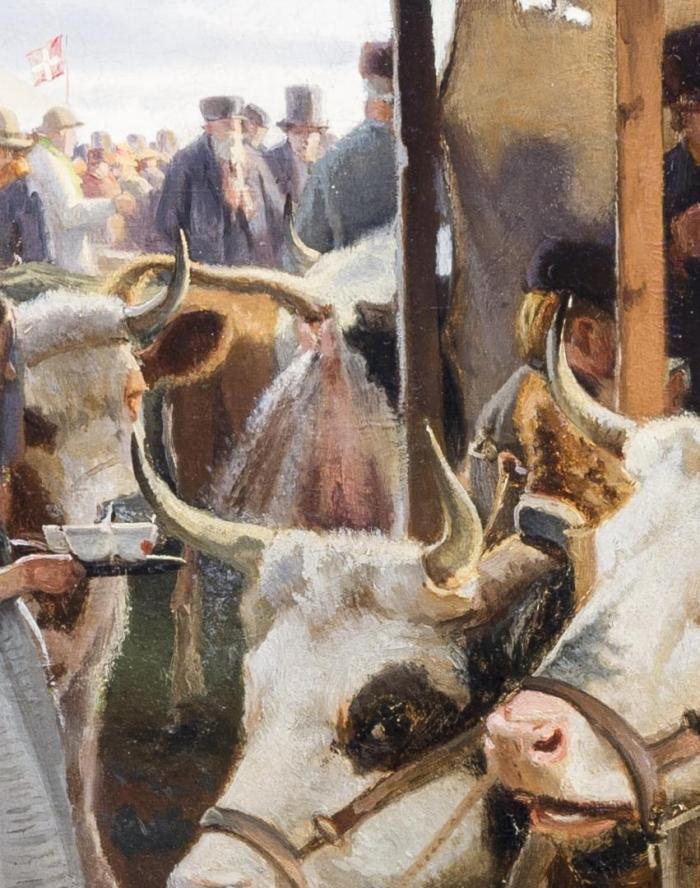

Market days in Jutland gave Smidth ample opportunities for conducting and collecting figure studies, and we know of several drawings and paintings on the theme, including Market Scene [fig.24] from 1894. The market-day atmosphere and the distinctive portrayals of the various human figures are redolent with cultural history, even as they also constitute interesting artistic subject matter.44

The painting shows how Smidth had attained full mastery of drawing and of the various painterly techniques. The picture plane has been fully filled out, and one senses the dynamic qualities of the foreground, middle ground and background alike. The festive atmosphere of the market scene is very palpable and vibrant, and small details continue to reveal themselves on the canvas. The painting is almost like a snapshot of an unfiltered reality. This impression is further accentuated by the cow to the left side in the middle distance [fig.25].

We can only glimpse its hindquarters behind the tent, captured at the very moment it raises its tail to pass water. One senses how Smidth would have painted this scene with a smile playing on his lips. When viewing this painting, any Danish observer will be likely to send a fond thought to Philipsen, who became known as the ‘cow painter’.

The bold choice of including a urinating cow demonstrates how Smidth’s art has conclusively parted ways from the kind of romanticising painting associated with older artists, such as the aforementioned Dalsgaard. Although Smidth retains his down-to-earth qualities, his feet are now firmly planted in a more modern view of art and of life around him. He now certainly engages in ‘art at first hand’, depicting reality as it is, for better and for worse. Alongside the sense of humour and subtlety, there is also an idyllic sheen that should not be mistaken for idealisation. By this point, Smidth’s love for and commitment to his chosen subjects has made him a compelling contemporary artist.

Breakthrough and artistic recognition

Smidth’s major breakthrough came in 1900 when the Copenhagen-based Kunstforeningen (The Art Society), headed by the artist August Jerndorff (1846–1906), arranged a vast retrospective featuring around 300 studies and drawings by Smidth. Almost all of these works were sold at the exhibition, including several sales to the tobacco manufacturer and art patron Heinrich Hirschsprung; a fact that also had a favourable impact on the subsequent saleability of his art. Smidth is awarded the prestigious Eckersberg Medal in 1905 and 1906, at which point he is further honoured by becoming a member of the Academy’s Plenary Assembly. Such prominent appreciation must have injected the artist with renewed energy and, not least, artistic self-awareness, which would have a conspicuous impact on the dating of Smidth’s works. While dates in the artist’s own hand never became frequent or consistent, one still sees that most of them appear on works created after 1900. His new self-image as a publicly acclaimed artist is also reflected in several self-portraits of the late years, including examples from 1905, 1910 and 1916.45

The painting Curious Bystanders by the Artist’s Tent from 1910 [fig. 26] also suggests an artist who is increasingly self-aware and confident, turning his labours into artistic subject matter in its own right. We are never told whether the tent conceals Smidth or some fellow artist. Be that as it may, the painting does offer insight into a working process that followed him throughout his artistic career; one where his easel and paintbox were steadfast companions on his hikes around the landscapes. Smidth engaged in plein-air painting all his life, but would also work out of doors to amass studies for paintings that were subsequently done at his Copenhagen workshop. As a result, his finished paintings are often pieced together from various studies done out in the open air.

The final years: Old themes and impressions of modern life

The atmospheric Eel Trapping [fig.27] from 1915 is among Smidth’s final paintings.46 As his palette grows lighter and more ethereal, the brush strokes also become wider, applied with a deft and very confident hand; the painting of eel trapping in the Limfjord is a particularly clear example of this mature style. More immediate in nature, this painting technique adds a sense of freshness and presence that gives Smidth’s simpler compositions additional power.

Despite having no date done in the artist’s own hand, it presents little difficulty to place his Landscape with Geese, Cows and Milk Churns [fig.28] among Smidth’s late works. The colour schemes and looser brushstrokes are reminiscent of Philipsen’s Impressionistic paintings from the island of Saltholm from the 1890s. One might say that Smidth’s influence on Philipsen’s decision to become an artist comes back to benefit himself here. Smidth’s artistic development and painting style are not the only factors assisting our dating of the work; the painting also includes several features that anchor it in a specific time – for example, milk churns arrived in Denmark as part of the cooperative movement in the 1880s. Most interesting of all for the purposes of a more accurate dating are the electricity poles on the left side of the painting. The first electricity plants appeared in Denmark in the year 1900, and the first rural plants arrived in 1905.47 The features seen in this landscape scene are unmistakable, enabling us to establish a significantly narrower window for its creation: from 1905 to 1917. The row of poles begins and ends in the middle of the road, meaning that they do not continue out of the picture or further along the road – a point which merits our attention. Obviously, power lines can only conduct electricity if they are connected to a power plant, and the poles in this painting do not appear to be so. Perhaps Smidth captured his scene while work on setting up the electricity poles was underway, or perhaps he added the poles to the landscape without taking into account how they would be positioned in real life.

Life in the countryside remained Smidth’s starting point throughout his career and he lived long enough to see how rural life changed as more modern times, inventions and customs arrived. Nørregaard-Nielsen’s quotation on Smidth’s relationship with his subject matter is relevant here, too: ‘his paintings contain neither any elegy for what is fading away, nor any rejection of the coming thing’.48 Smidth painted life as it unfolded around him with a passionate interest in what he saw, sensed and perceived.

Concluding remarks

Smidth’s death on 5 May 1917 marked the end of a long and unusual life in the service of art, one which had yielded a wealth of works ever since 1860s. However, several of those works have become somewhat homeless in the chronological narrative of the artist’s life, which may be due to the absence of dates done in the artist’s own hand. The purpose of this article has been to explore the challenges involved in dating the artist’s works; challenges that present difficulties for those wishing to apply a chronological and biographical outlook on the artist and his oeuvre.

The act of dating undated material is, of course, associated with a number of reservations. The very broad time brackets that accompany many of Smidth’s works can be seen as expressions of a tentative and cautious approach to the artist’s material, one where the author does not want to rule out any potential dates. In the vast majority of cases, it can be difficult to assign more accurate dates due to a number of issues that have been reviewed in this article, including the fact that Smidth recycled his sketches and remained a close affinity with the same subjects throughout his life. Conversely, Smidth’s artistic development can help us identify and pinpoint differences in technique and stylistic expression which can, in many cases, help place a work early or late in Smidth’s career. However, it should be noted that Smidth’s more frequent dating of his works in his later years may have a correlation with the growing recognition of his art. A chronological and biographical approach makes it possible to place a number of works within a specific period, providing us with narrower time brackets and reaffirming those individual works’ position in Danish art and, not least, in the treatment of Smidth as an artist.

In 1914, the author Johannes V. Jensen offered the following description of Smidth:

Hans Smidth remained ‘undiscovered’ for a long time. While Danish painting underwent more than one crisis during the last 30 to 40 years under the influence of various movements, schools and fashions […],Hans Smidth had the courage to be entirely himself, and, what is even braver, to be so unnoticed, without an audience, without the press, without a career, bolstered only by the quiet satisfaction offered by honest, genuine work. Time has vindicated him.49

The quote demonstrates how Smidth was perceived as a so-called ‘peculiar blend’, as Hohlenberg put it in his eulogy. But the renewal of Smidth’s artistic expression came not only came from within, as described in this article – he was also open to external influences; for example, from his fellow artists and their sources of inspiration, as well as from art he encountered at exhibitions in Copenhagen. External influences on Smidth have not previously been the subject of in-depth study, an omission with may be due to the sparse biographical material available. This lack has shored up the general narrative describing Smidth as a quiet and introverted artist, and the shortage of accurate dating has further anchored the enigmatic aura surrounding him. In spite of his introvert qualities, Smidth nevertheless influenced other artists, including Th. Philipsen and Anna Ancher. In some ways, the enigma surrounding Smidth has also contributed to him having a rather invisible position in Danish art, exacerbated by his indeterminate place between the main camps of Danish nineteenth-century art.

Smidth may have gone his own way on the Jutland moors, but he was not the isolated figure he has been made out to be in much Danish art history writing. He influenced and was influenced by other artists. When considering these relationships, the nuances of his art become even more prominent, and the mystery recedes.