Summary

From happy mediocrity to doom and gloom – that is the result of not sticking to one’s last, according to the moral of the tale of a cobbler who wins the lottery. This essay looks at C.W. Eckersberg and J.F. Clemens’ six-print graphic series The Lottery Ticket (‘Lotterisedlen’), which was published in 1815-1816. The print series and original sketches provide insight into the economic conditions of the period, the scourge of the lottery, and the controversy surrounding the Jewish population of Copenhagen in 1813, which ended in physical violence in 1819-1820.

Articles

C.W. Eckersberg (1783-1853) was still a student at the art academy in 1808 when he made the six drawings about the cobbler and the lottery ticket.1 He had come to Copenhagen from Southern Jutland in 1803, and had won both minor and major silver medals, as well as the minor gold medal in the competitions held regularly by the academy. He won all three in 1805, qualifying him to compete for the main gold medal. This was key, because it granted him access to a travel stipend, which would give the young artist the opportunity to complete his studies by visiting the antique masterpieces of Rome.

The competition for the main gold medal was not held every year, but in 1807 Eckersberg tried his luck – and failed.2 In 1808 there was no competition, so Eckersberg channelled his energies elsewhere, dividing his time between studying the historical subjects that would prepare him for the gold medal competition, and the more popular, genre paintings that put food on the table.3 During the previous year he had embarked on a collaboration with the engraver Gerhard Ludvig Lahde (1765-1833), resulting in the publication of graphic prints depicting current events like the fire at Copenhagen cathedral during the 1807 Battle of Copenhagen.4 After this Eckersberg was involved in the production of the series Danske Klædedragter depicting folk costumes from throughout Denmark by Lahde and the Swiss artist Johannes Senn (1780-1861).

Graphic series like these could reach a wide audience and provide a good source of income. Eckersberg was aiming to be a history painter, but did not turn his nose up at such popular, everyday motifs, even though they were a long way from the historical, mythological and religious subjects preferred in academic circles. They made it possible for him to earn a living, so the collaboration with Lahde continued, and he also started to work with the engraver Johann Friderich Clemens (1749-1831). Clemens became an important figure in Eckersberg’s life, and the young artist often came to the older engraver for advice on professional matters as well as personal issues, like Eckersberg’s divorce from his first wife. Later they were professorial colleagues at the art academy, and Eckersberg painted Clemens’ portrait in 1824.5

The Cobbler and the Lottery Ticket

Eckersberg drew the originals for The Lottery Ticket in 1808, the year between the academy competitions. They are pen and pencil washes painted in shades of brown and grey with some contours and lines highlighted in pen and ink. With the exception of the first, all the prints are dated and signed ‘E inv. [invenit] 1808’ in the lower left-hand corner. But Clemens did not start to make etchings of the series until 1815, so they languished in his drawer for quite some time. Eckersberg presumably either sold or gave the drawings to Clemens, since they were in the engraver’s possession when he died.6 In the meantime, Eckersberg had won the academy’s main gold medal in 1809, and was able to travel abroad in 1810.7 He was therefore in Rome when Clemens started working on the series. In a letter dated January 1815, Clemens writes that he has started working on the story of the lottery ticket. Eckersberg writes a reply to his friend and mentor saying: ‘It gladdens me that the lottery drawings are among your current works, but there are, perhaps, a good deal of corrections to be made, especially in the design, et cetera.’8

Clemens then writes to say that he anticipates a high level of interest in the series, and explains what he intends to do technically: “[…] all who see the drawings express a strong desire to own them. I am working with eau-forte, using the burin combined with aquatint, and the changes are minimal.”9 In May 1815 Eckersberg was still concerned about the quality of the drawings:

It gratifies me that the good Mr Clemens is well employed with work on the Lottery Ticket and in anticipation of healthy returns. I would, perhaps, have wished that I myself could have improved each of the drawings in advance, not, you understand, in their composition, but in the sketching, line, perspective and such, which I may have overlooked in my fervour at the time. It strikes me that the nature of the content of these prints is far from uninteresting, in addition to which, I consider them to be among the most successful works I have done.10

There were, however, no major changes: the drawings and etchings are almost identical. Clemens did not correct the anatomical mistakes the still unpractised Eckersberg did in fact make. The cobbler’s wife’s ear, for example, has slipped down her cheek in the first drawing, and this obvious beginner’s mistake has not been corrected in the etching. There is, in fact, only one major difference between the originals and the finished prints, but it is a significant one. On which more later. First, a summary of the story told in the prints.

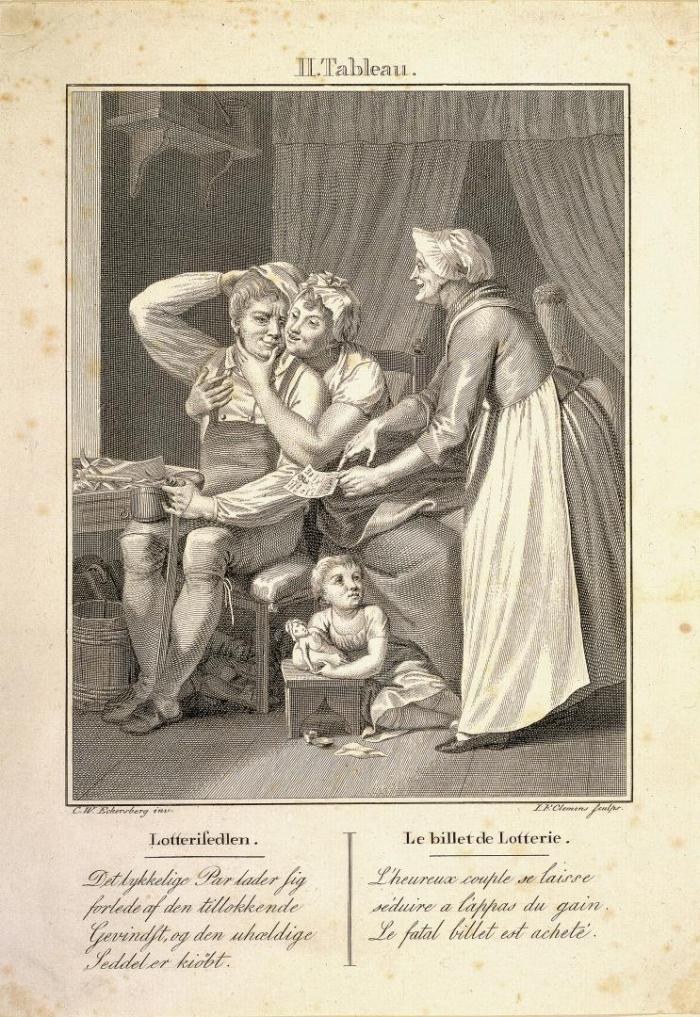

In the first image [fig.1] we see how a simple life with wife and child is full of happiness by the fireplace in the cobbler’s home. They live a humble but honest life.

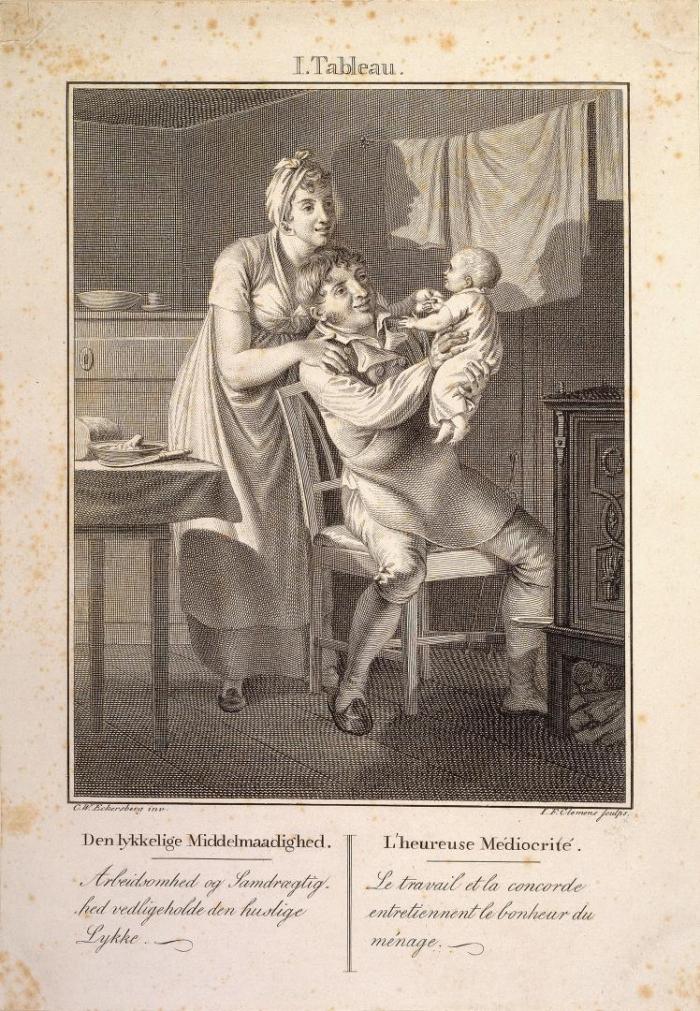

In the next scene [fig.2] the cobbler’s wife cajoles him into buying a lottery ticket from the old woman (a lottery agent) selling them. He scratches the back of his head, and his eyes reflect daydreams of a life other than the one he lives by his last. His daughter, who is now old enough to play with dolls, is an innocent bystander.

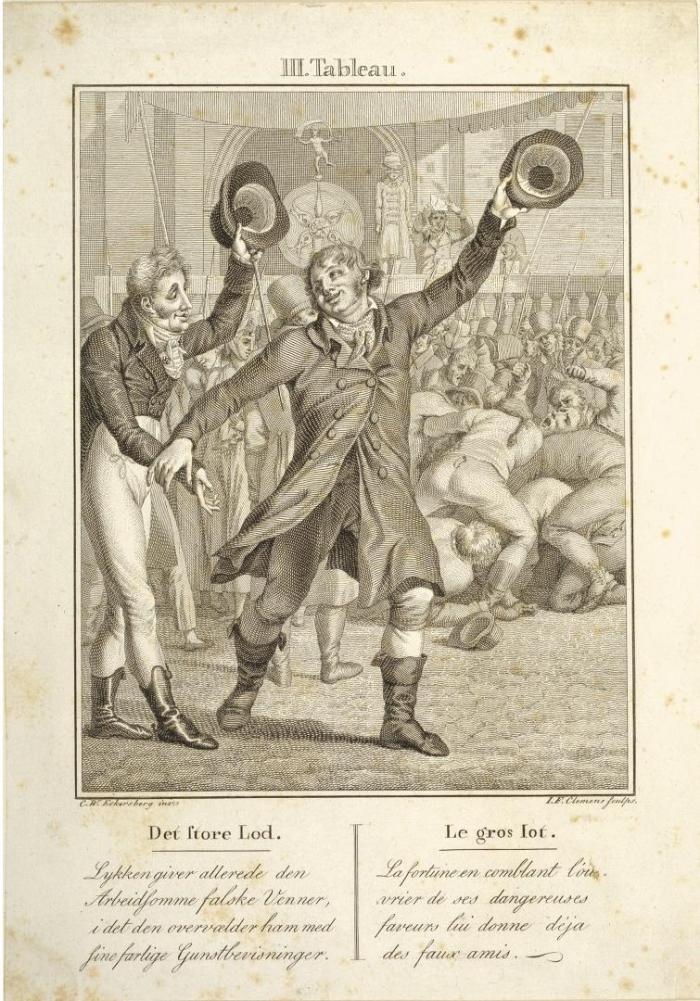

He has a winning ticket! The cobbler waves his hat enthusiastically as his number is called out in the background of the third scene. [fig.3] The goddess of fortune balances on top of the lottery drum. A blindfolded child from an orphanage fishes the tickets out of the drum – a lottery tradition in Copenhagen, but also abroad.11 A group of men scramble to grab the tickets thrown as alms to those who could not afford to play the lottery. An overly jovial man stands ready to advise lucky winners with no previous experience of wealth. The text at the bottom refers to false friends.

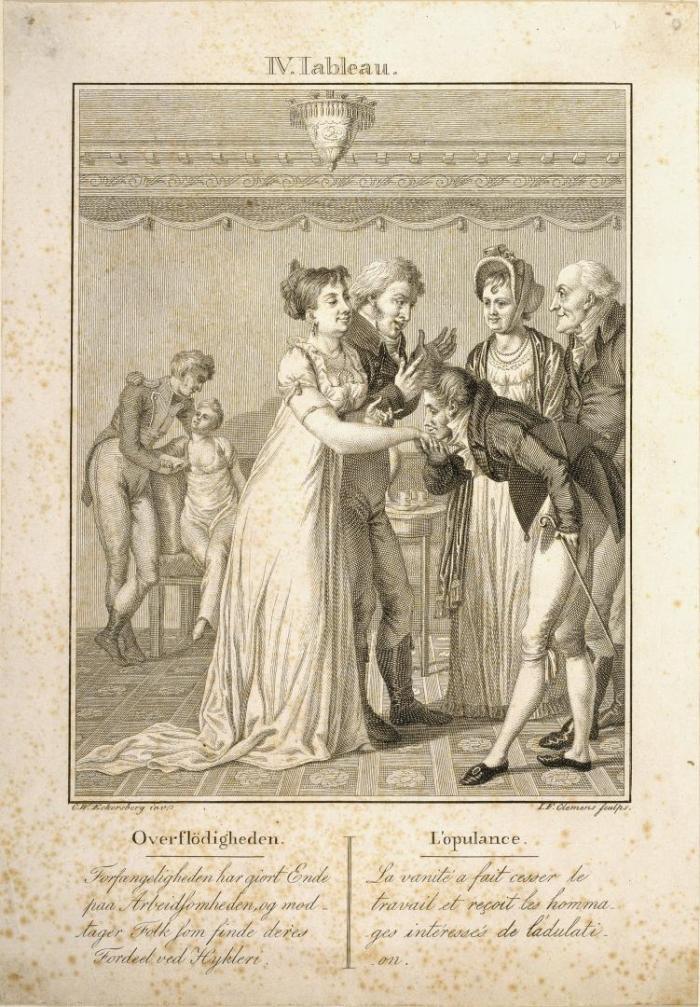

The cobbler spends his fortune in no time. In the fourth scene [fig.4] we see the cobbler and his wife at a society gathering where hands are kissed and people flirt under crystal chandeliers. The cobbler’s wife is wearing a dress with a plentiful train and an enormous necklace.

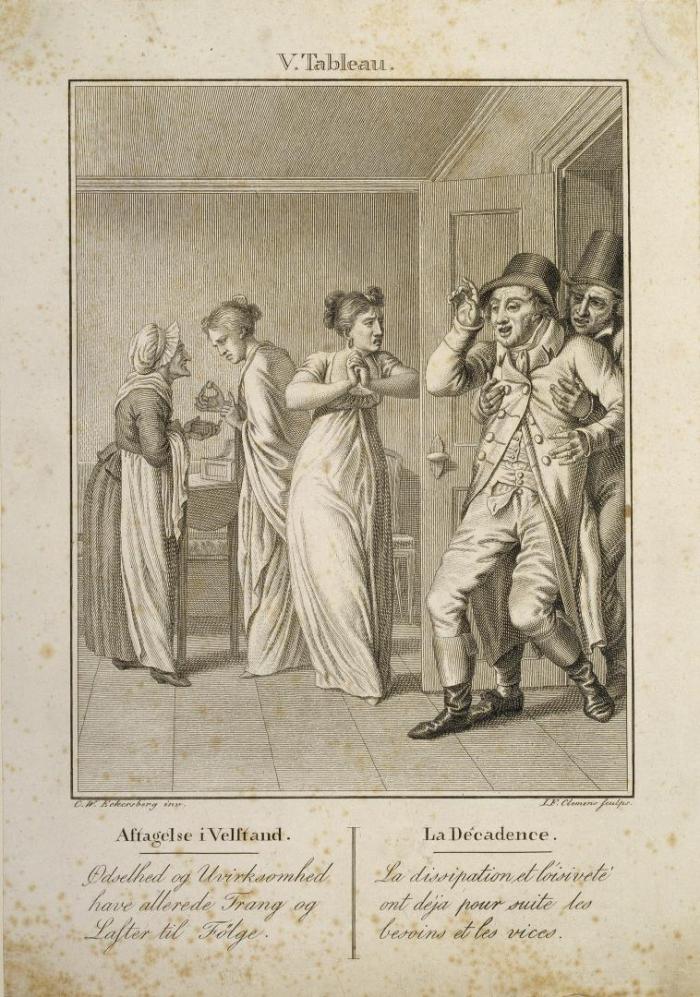

Their happiness and winnings cannot, of course, last forever, and the imprudent cobbler, having forgotten how to work for a living, takes to drink. In the fifth scene [fig.5] he comes home drunk and dishevelled, and his wife and now adult daughter have to pawn their jewellery.

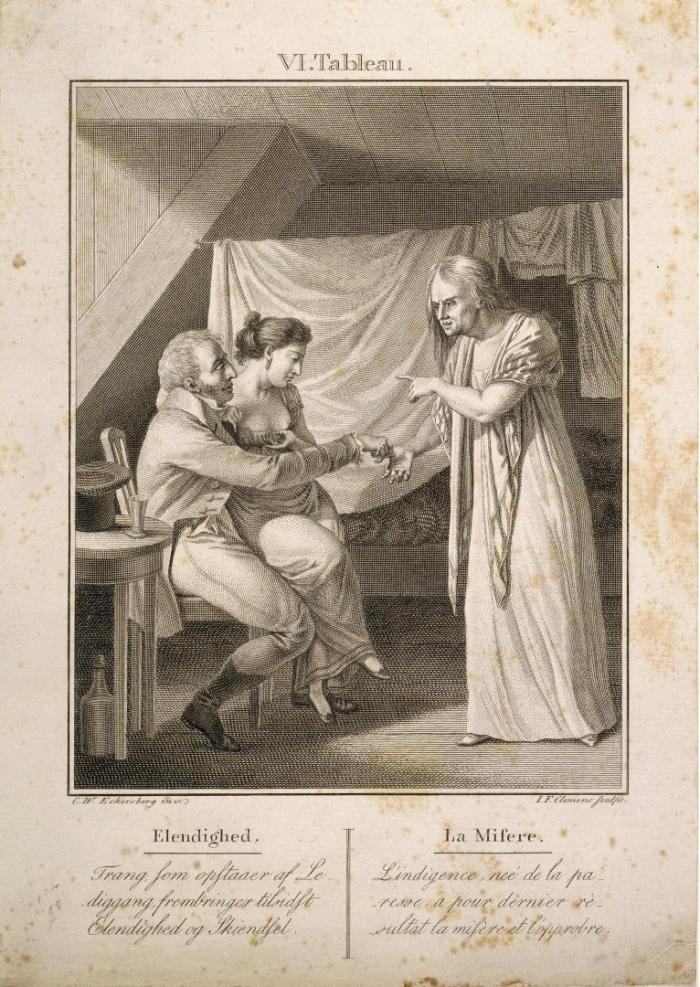

In the last scene everything has gone to rack and ruin. [fig.6] The cobbler is gone, and since the jewellery is also long gone his wife has to sell her daughter’s charms to strange men in a rundown garret. This marks the end of the downward spiral for the previously hard-working cobbler and his family.12

On a Winning Streak?

Both the number lottery and state lottery were popular at a time when Denmark’s economy had hit rock bottom and many people were looking for quick gains.13 The Napoleonic wars had been an economic disaster for the state of Denmark, which came close to bankruptcy in 1813. Inflation soared, and the inevitable currency reform that followed left many in serious difficulties (events that have often – mistakenly – been described as state bankruptcy). In the foreword to the currency reform bill, Frederik VI wrote:

Since the legal tender of the nation has been shaken to its very foundations, we have taken it upon us to create the order and stability necessary for a lasting and secure fundament […] the common good demands sacrifices by each and every one of us. The hardships incurred by such sudden and all-encompassing change can only be seen as contributions in the interests of the fatherland.14

The king’s appeal to understanding from his subjects was not strictly necessary: as an absolute monarch he could do as he wished, and the reform was, after all, a necessary measure in heavily turbulent times. At a more modest level, lotteries contributed to the empty state coffers, since the profit generated fell to the state to pay for poor relief and the national debt. Despite which, the lotteries met harsh criticism because the money they raised caused so much hardship, including desolation and ludomania. In 1800 one critic told the tale of a poor mother who undressed her child at the lottery office and swapped its clothes for a lottery ticket – inevitably not a winning one.15 Whilst this might have been an over-dramatic anecdote, it expressed some of the concerns caused by Denmark’s lotteries, and how desperate people were to take a chance. Many gambled more than they could afford. The number lottery was particularly problematic, because the tickets were so cheap that it was open to just about everyone.16 This is also the reason it was eventually abolished, although not until much later in 1851.17

A Danish ballad from 1802 makes fun of a man – also a cobbler – who dreams he has the winning lottery numbers at night, but wakes to bitter disappointment.18 Like the anecdote about the child’s clothes exchanged for a lottery ticket, the ballad shows how widespread playing the lottery was, and how many people paid with their own money to make fools of themselves. The dreaming cobbler is so sure of winning that he asks his wife to throw out all their old, shabby furniture while he is at the lottery. As a result, when he is carried home after fainting at the loss of all his money, it is not only the winnings he has lost, but also all his household furniture.

J.F. Clemens’ biographer, J.C. Fick, notes that the idea for The Lottery Ticket similarly came from verse, in a poem allegedly penned by Oluf Olufsen Bagge (1780-1836).19 Bagge was a close friend of Eckersberg, and a student of Clemens. The poem was originally to have been printed with the etchings, but in the end a more prosaic, explanatory text was printed in Danish and French under each etching.

Eckersberg’s work was among the critical voices, but whereas ballads like that mentioned above simply pointed the finger of scorn, Eckersberg’s mission was more fundamental. He problematizes the very raison d’être of the lottery (at least, from the lottery player’s rather than the agent’s perspective) by showing that the chance of winning and suddenly being propelled from the honest class of artisans to the upper classes removes people from where they belong, as a result of which they perish. Since the tale ends with prostitution, not only is the cobbler’s family ruined, but morality at large suffers too. The cobbler in the ballad is the object of ridicule, but Eckersberg’s family is destroyed by being unlucky enough to win. Even though their rise and fall might have some entertainment value, the moral of the tale is unmistakable.

It was a subject that obviously interested Eckersberg. He also painted other lottery scenes, including one depicting the grimaces of a winner and a loser. [fig.7] Perhaps most interesting here is the gentleman with the lorgnette spotting the winner in the crowd. This elegant dandy has a counterpart in the third print of The Lottery Ticket, where the cobbler has won. A swindler immediately approaches the newly prosperous fool with advice: the outcome of the encounter is easy to predict.

Eckersberg may have had a highly personal reason for his interest in the lottery. In records of the divorce from his first wife Christine Rebekka Hyssing, it emerges that she had a penchant for playing the lottery. After Eckersberg’s departure for Paris, she ran into serious difficulties, stealing a silver-studded pipe and letting her apartment to two tenants simultaneously, despite the fact that only one of them could live there.20 During the divorce proceedings she told the authorities that she had meant no harm, indicating that she needed money to play the lottery. Eckersberg was apparently aware of this while still living in Copenhagen:

[D]uring the time we lived together, he did not attempt to curtail this compulsion of mine. He, like myself, cherished the hope that I would one day be able to develop a more fortunate constitution. That, during his absence, I pursued it, can only be excused by my being left entirely to my own devices, pursuing this proclivity without restraint in the hope of meeting good fortune, by which I would be in a position to reward my husband’s love and ensure him a more clement future. This was not to be my fate. My compulsion to play the lottery has brought misery to others than myself.21

Eckersberg drew The Lottery Ticket in 1808 before he left for Paris, and before Christine Rebekka had stolen and committed fraud to finance her gambling. Her statement, however, more than intimates that her compulsion was evident as early as 1808, and that Eckersberg was aware of it. He thus had the problems caused by the lottery at close quarters when he made the work, and was able to draw on his own personal experience.

The Disappearance of the Jew

Only one of Clemens’ etchings is different to Eckersberg’s original. The fifth print shows the cobbler’s wife trying to pawn her jewellery to an old woman, whereas in Eckersberg’s original drawing the pawnbroker is a caricatured, Jewish figure. [fig.8] The Jew in the drawing is represented using stereotypical features with a long history: a crooked nose, full beard and sneering grin. He is also so short that the cobbler’s wife has to bend over to negotiate with him. His clothing, however, would not distinguish him to any major extent from his Christian contemporaries. His coat and boots are just like the cobbler’s. As a Jew, he is wearing his hat indoors, just like the cobbler and his assistant, who arrive drunk and forget to remove their hats. All three are thus depicted as lacking manners. The hat the pawnbroker is wearing also has nothing Jewish about it. He is wearing a bicorne, the hat worn by Napoleon in the same way as Napoleon wore it, with the tips pointing to the sides rather than the back and front.

Napoleon ratified the emancipation of French Jews brought about by the revolution in 1791, and wherever he went the conditions of Jews improved, especially with the repeal of the ghetto laws that had forced Jews to live in specific areas and stay indoors at night.22 When the Austrian emperor Franz I (1768-1835) asked his ambassador in France, Prince Klemens von Metternich (1773-1859) to report on the situation in 1806, Metternich told him that the Jews saw Napoleon as a messiah who had come to free them at last.23 It is possible that by wearing his hat in the style of Napoleon, the pawnbroker was paying tribute to this messiah of the Jews. On the other hand, this kind of hat was not uncommon, so it could also simply have been part of his everyday clothing. For centuries Jews had been forced to wear special garments or badges, so when possible, as in Copenhagen, more assimilated Jews avoided wearing them. Satirists soon latched onto this, and in Austria, for example, Jews were caricatured as trying to blend in with their Christian compatriots by wearing lederhosen.24

As mentioned above, Eckersberg was in Rome when Clemens started working on the series, so it is unlikely that he drew a new original for Clemens after deciding to change the figure. The old woman who replaced the Jew is the same as the lottery agent from the previous drawing, just inverted. This provided a basis for the revised engraving, but why did Clemens make such a major adjustment when no other changes were made to Eckersberg’s original?

The Jewish Literary Feud

An explanation of the change can be found in a heated controversy about Judaism and Denmark’s Jewish citizens that emerged between Eckersberg drawing his originals in 1808, and Clemens’ making the etchings in 1815. The controversy has been dubbed the ‘Jewish Literary Feud’ and took place in 1813. This was the same year the state of Denmark almost went bankrupt, and in the face of the desperation caused by economic turbulence and the general pressure Denmark was under internationally, people were looking for scapegoats.

The starting signal was the poet Thomas Thaarup’s (1749-1821) publication of his translation of the German Friedrich Buchholz’s heavily anti-Semitic book Moses und Jesus from 1803.25 Thaarup added insult to injury in his long foreword, where using even stronger terms than Buchholz he expounded on the alleged untrustworthiness of Jews. The foreword includes insults like depicting Jews as idle: “Eating his bread by the sweat of his brow, something applauded by other nations, is a curse for the Jew. A land of milk and honey and lazy days in the shade of the fig tree are apparently more to his liking.”26Thaarup also questions the patriotism of Danish Jews, asking whether their primary loyalty is to ‘the Jewish Nation’ rather than the state of Denmark:

This is reliant, in my opinion, on proving that the peculiar religious principles to be found in their tomes have been rejected by the nation today, are no longer studied in their schools, are no longer preached in their synagogues, and can no longer be traced in the writings of more philosophical writers today. Here I speak of the idea of a national god who solely loves the nation of Jews, the promise of world domination based on the subjugation and ruination of all nations, and the exemption from fulfilling ordinary moral duties for non-Jews, the consequence of which is a hostile disposition against all those they call Gojim, Nochrim and Accum; that in culture they stand alongside other enlightened citizens and follow in their footsteps; that in learning, crafts and trades they, like other citizens, promote the prosperity of the state, and in times of war, like them, defend it. This, I fear, will prove difficult to prove to our satisfaction. On the contrary, it appears that self-interest, cruelty and indolence have been this Nation’s distinguishing features since its very origins.27

During this period of war and crisis, patriotism was probably more in focus than at other times. Frederik VI (1768-1839) had shown himself to be entirely open-minded in his attitude to Jewish immigrants, who prospered in the Danish capital as a result.28 This peaceful coexistence was threatened by Thaarup, who apparently considered himself an expert on patriotism, having penned the inscription for the Liberty Column in Copenhagen in 1797. His attack on Jews was not slow to provoke a reaction, and numerous Jewish and Christian debaters rushed into print.29

The lawyer Johan Hendrich Bärens (1761-1813) was a key opponent, but died suddenly in the midst of the debate in July 1813. Bärens had been a tireless advocate for education and the poor, something symbolised by him choosing to be buried in a paupers’ grave. Although not a Jew himself, he was also active in a society established to secure the admission of Jewish youth to Danish crafts and trades. In his pamphlet Tillæg til Moses og Jesus (‘An Addendum to Moses and Jesus’) he attacks Thaarup’s points directly:

Both Moses and Jesus and the preface of the translator mislead the masses instead of enlightening them, causes hate and contempt of Jews, pitches citizen against citizen, and indirectly indicts the government. […] furthermore, the Jews of Copenhagen, numbering some 2,400 with wives and children, are too few to warrant attention, and fulfil their moral duties as well as Christians […] in learning, crafts and trade they do as much, if not more, for the community of citizens as Christian tradesmen […] likewise in times of war they have defended the city and fatherland […] their endeavour is to win the respect of Christians.30

This feud drew attention to discrimination against Jews, and in 1814 they achieved civil rights on almost the same terms as other Danes. The feud was without doubt the impetus the king needed to take this necessary step for an enlightened absolute monarch. Napoleon’s emancipation policy had already proven an example to improve the conditions of Jews for most of Europe, including powerful Prussia and tsarist Russia, partly to avoid the emigration of wealthy Jews to enemy France.31 Frederik VI thus had plenty of role models, something also apparent in a letter to the king from Prime Minister F.J. Kaas (1758-1827), who had drawn up the decree as early as 1807: “The change in the conditions of the Jews in France attracted my attention; I believed it necessary as far as possible to anticipate the effect of the results on Denmark by giving the Jews a more established civic status in the State.”32

With the Jewish Literary Feud in mind, it becomes clearer why Eckersberg and Clemens abandoned the caricatured figure of the Jew in 1815. Now that the battle lines had been drawn up by Thaarup and his opponents, they risked falling into the camp of the anti-Semites: the ridicule of Jews continued to flourish at the Royal Theatre, for example, for decades to come.33 But Eckersberg and Clemens did not feel at home on this side of the conflict, in addition to which it would have been bad for business. Since making the original drawings, Eckersberg had also met Mendel Levin Nathanson (1780-1868) through Clemens. Nathanson was an influential Jewish patron of the arts,34 giving Eckersberg another reason not to publish anti-Semitic caricatures.

Later Eckersberg painted portraits of key Jewish figures, including the head master Gedalia Moses (1753-1844), the merchant Joseph Raphael (who died in 1837), and Nathanson and family.35 The wealthy, Jewish bourgeoisie needed an artist who, with a little help and advise from the older and wiser Clemens, had avoided what could have proven to be a serious failure of judgement businesswise.

Finally, it is also possible that Clemens knew the lawyer J.H. Bärens, an advocate for Jews in Denmark, personally. Bärens’ mother, Magdalene Margrethe Bärens (née Schäffer, 1737-1808), was accepted as a student at the Royal Academy of the Arts in 1779, and became its first female member in 1780.36 Clemens was accepted in 1778, and cannot have avoided being aware of the presence of this remarkable woman at the academy. As well as being a lawyer, her son J.H. Bärens was also artistically gifted, passionately interested in art, and on at least one occasion reviewed the gold medal exhibition at the Royal Academy.37 It is therefore likely that Clemens knew Bärens and was aware of his clear position in the Jewish Literary Feud, which would have made publishing a caricature like Eckersberg’s distinctly uncomfortable.

The Jewish Literary Feud had a violent sequel in 1819-20, when Jewish shops and homes in Copenhagen were attacked. The pogroms had started in Würzburg on August 3rd 1819, after which they spread throughout Germany, to Prague, Krakow, Vienna, Graz, Copenhagen and all the way to Helsinki. On Saturday September 4th a mob started to smash the windows of the merchants Raphael and Jacobsen. Pawnshops were looted, and Jews were attacked and beaten.38 The rioters demanded that Jews be banished from the city, and the Copenhagen police underestimated the seriousness of the situation to such a catastrophic extent that after several days of rioting the king had to summon the military.39 During the following months there were minor episodes, including the windows of Nathanson’s shop being shattered, but the incidents were rapidly contained.40 On the king’s birthday in January 1820, a bill dubbing him ‘King of the Jews’ was posted on the city walls, and at a subsequent Shrovetide celebration in Frederiksberg it was noted with outrage that a Danish Shrovetide barrel, traditionally battered until it fell apart, was decorated as a Jew.41 The Jewish Literary Feud of 1813 can thus be seen as a prelude to the anti-Semitic violence of five years later.

English Role Models

The final prints of The Lottery Ticket have explanatory captions in Danish and French, showing that Clemens and Eckersberg were hoping for an international audience, and with good reason. Moralistic series like The Lottery Ticket were popular and circulated throughout Europe. The English artist William Hogarth (1697-1764) was a strong source of inspiration for Eckersberg and Clemens, publishing series with the same, moralistic humour, like A Harlot’s Progress (1732) depicting the moral corruption of a young woman, and A Rake’s Progress (1735) depicting the road to ruin of an equally naïve heir. In 1808 Eckersberg had also painted a series entitled En falden piges historie (‘The Tale of a Fallen Girl’), which was engraved by G.L. Lahde in 1811. With its theme of prostitution, the series would appear to have been directly inspired by A Harlot’s Progress.42 Both series follow a beautiful, innocent, young woman, who due to falling on hard times and her own carelessness ends up in the hands of unscrupulous procurers and lascivious men.43 In Hogarth’s series, the main character dies of syphilis. Eckersberg’s version was less harsh yet no less tragic, with the girl ending as an ageing beggar.

An article in the weekly newspaper Nyeste Skilderie af Kjøbenhavn (‘The Latest Pictures of Copenhagen’) in 1817 shows that Hogarth’s popular prints were well known in Denmark. In an essay with the title ‘The Imitation of Real Lives on Stage’ his satire is used as an example, albeit in a text about theatre rather than art.44 Graphic prints were affordable and easy to distribute, and therefore also reached collectors in Denmark. Clemens had many of Hogarth’s prints in his collection when he died, including the wedding scene from A Rake’s Progress, five out of six of the prints in Mariage à la mode, the twelve print series Industry and Idleness (which like The Lottery Ticket moralises on indolence), as well as single prints of Beer Street and Gin Lane.45 He was doubtlessly familiar with a lot more of Hogarth’s work, not least from living in London for three years from 1792-95.

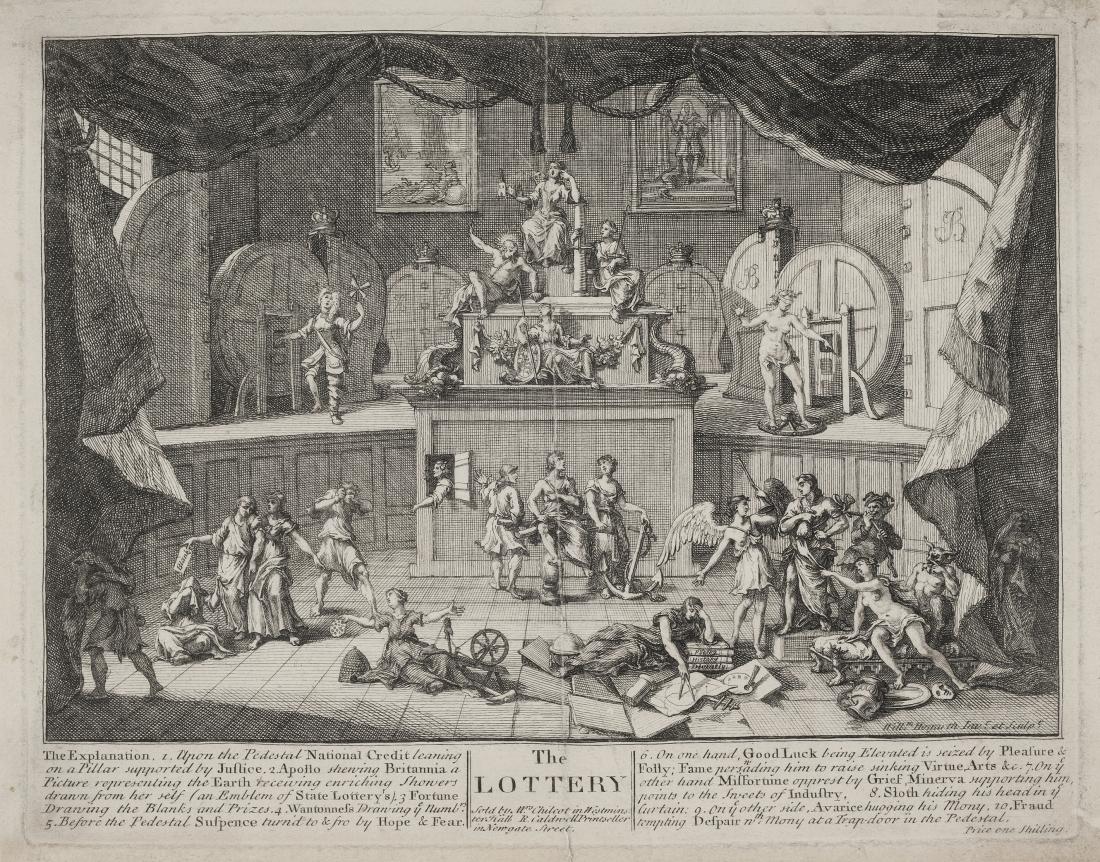

Hogarth also published a critical work on the lottery. [fig.9] The print is not an everyday tale like that of Clemens and Eckersberg, but an allegorical depiction of how the state income generated by the lottery was based on the financial ruin of its citizens, something also implied less directly by Eckersberg. Hogarth explains his allegorical figures in the text under the image, which includes the words “Apollo shewing Britannia a Picture representing the Earth receiving enriching Showers drawn from her self”. The figure of ‘Good luck’ is seen being seduced by ‘Folly’, and ‘Pleasure’ looks askance at the suggestion of ‘Fame’ to spend the winnings virtuously on the arts and sciences. On the other hand, the goddess of wisdom Minerva recommends that ‘Misfortune’ personified turns to the sweet rewards of hard work represented by a thrifty beehive and full honeycomb. ‘Fortune’ also features as it does in Eckersberg’s work, but as a blindfolded figure pulling lottery tickets out of the drum.

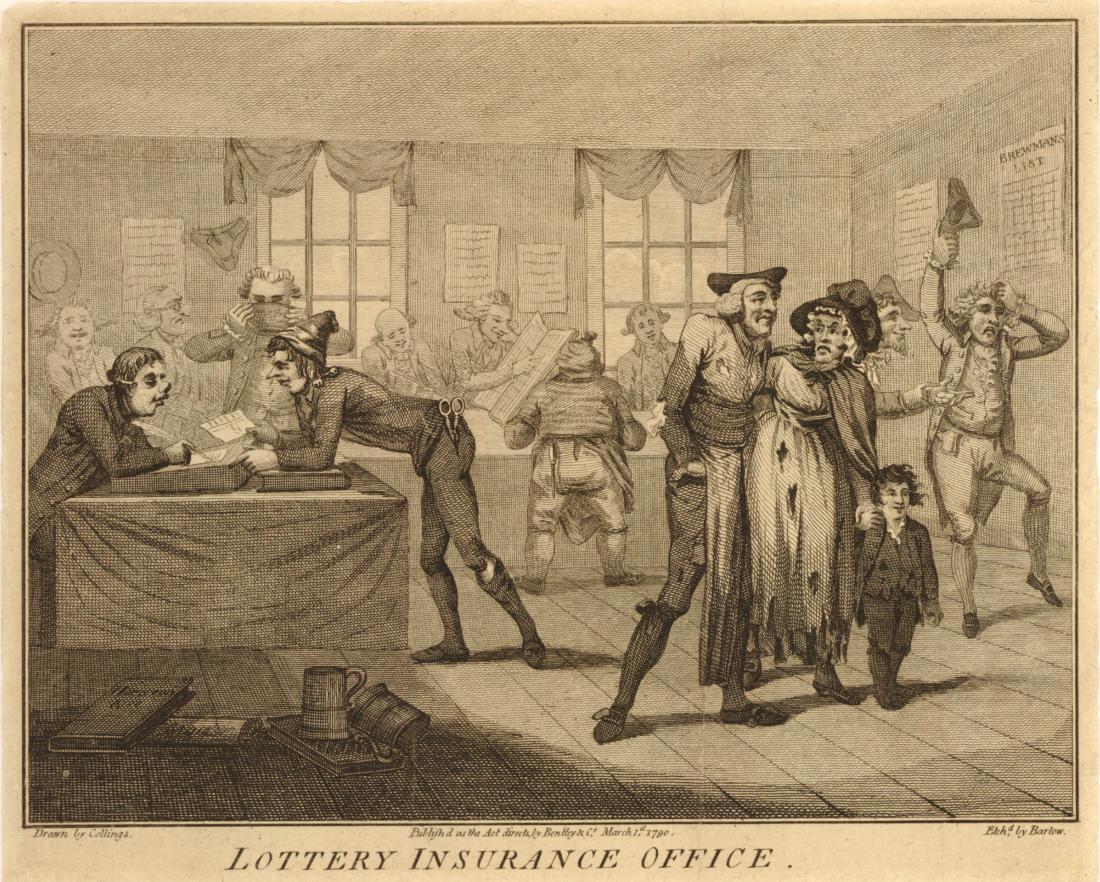

Hogarth was not alone in his criticism of the state lottery. There were numerous satires on the subject in the 1700s and 1800s. In 1790 John Barlow (1759/60- c. 1810) published Samuel Collings’ (active from 1784 until his death in 1795) satirical print Lottery Insurance Office, [fig.10] poking fun at the offices that sold shares in lottery tickets and fake guarantees against losses. Here a disappointed gambler is seen being offered a loan to continue to play the lottery by a ‘wheedling’ Jewish figure.

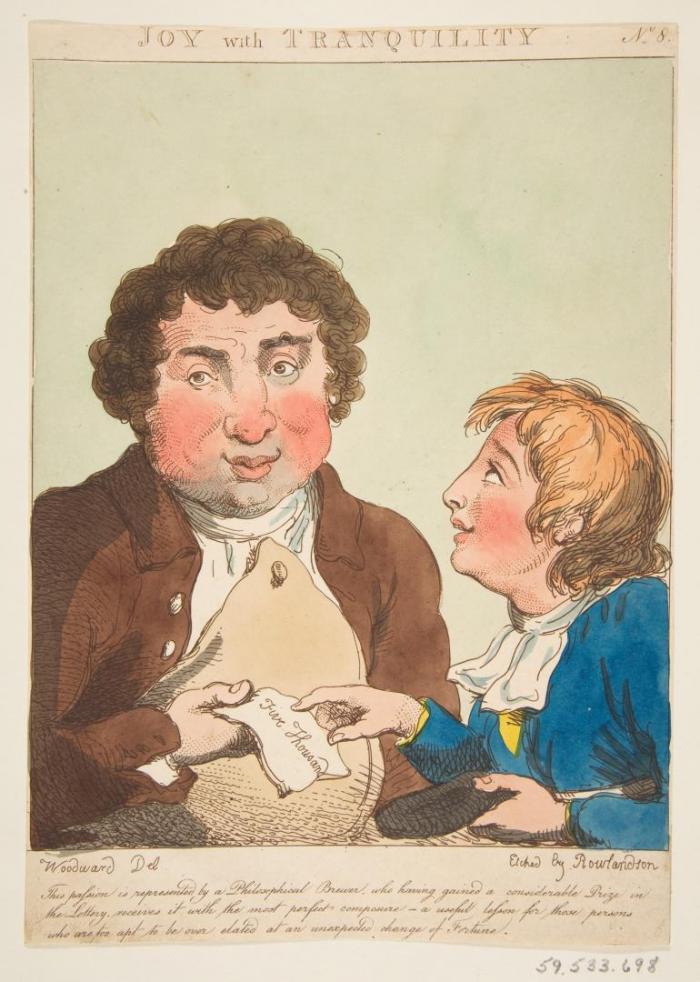

In the series Le Brun Travested, or Caricatures of the Passions from 1800, Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) and George Woodward (c. 1760-1809) ridiculed templates for artists that reproduced facial expressions and emotions. In the print Joy with Tranquillity [fig.11] a philosophically-inclined brewer has had a major win on the lottery, something he accepts with exemplary calm: “a useful lesson for those persons who are too apt to be over elated at an unexpected change of fortune”, as the caption states. Prints like these show the extent to which the lottery was part of everyday life in both England and Denmark, as was criticism of it.

An Unsound Mind in an Unsound Body

It is easy to identify good and evil characters in the works of Eckersberg and his English colleagues. They all operate with the idea that appearance reflects character, a common psychological understanding of the time and an enduring feature of caricatures. Good characters are always beautiful, and evil ones ugly, making it easy for anyone who bought the series to understand the story at once.

The Swiss priest Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) researched this connection, developing the pseudo-scientific system of physiognomy to identify links between character and facial features, claiming, for example, that criminals could be identified by the shape of their ears. In his book Physiognomische Fragmente, he also represented Judas as a stereotypical Jew, elaborating on the link between his crime and his physical appearance.46

Physiognomy was much discussed, and its validity as a scientific discipline was disputed by many. Prominent among them was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), who in The Phenomenology of Mind (1807) was contemptuous of these correlations, arguing instead that any symbols and meaning in nature were of human invention. In terms of content, he wrote, ”[t]he observations offered on this point […] sound just about as sensible as those of the dealer about the rain at the annual fair, and of the housewife at their washing time.”47 Despite such debates, Eckersberg still exploits popular beliefs that inner and outer beauty, like inner and outer ugliness, are related. Such beliefs are apparently something the entertainment industry today continues to play on, and studies have shown that attractive people are paid higher wages and have better positions than their less attractive colleagues.48

Eckersberg uses common perceptions of the relationship between inner character and outer appearance at several points in The Lottery Ticket. The character of the Jewish pawnbroker obviously plays on his grotesque outer appearance mirroring his poor character. The appearance of the cobbler’s wife changes drastically from the first print, where she is attractive – and happy and humble – to the second print, where her face is bloated and ugly as she fantasises about unearned riches and coaxes her husband to buy the fateful ticket. In the last scene, where she is acting as a procuress for her own daughter, she is aged and haggard to the point of being unrecognisable. In a similar manner, the lottery agent is far from a vision of beauty, something attributable to her role of persuading the cobbler to ruin himself: lottery agents were figures of popular disdain.49 Only the young daughter remains beautiful to the end, but then again she has played no part in the unfortunate affair.

Anti-Semitism?

The Lottery Ticket’s simple, easily comprehensible story and the means used to tell it, like the exaggerated links between inner character and outer appearance, also give us a hint as to why Eckersberg initially drew the caricature of the Jew. The question that remains, is whether Eckersberg was anti-Semitic? In today’s Denmark it would be controversial to draw this kind of caricature of a minority with the intention of publishing it, but was this the case in the early 1800s, before the Jewish Literary Feud?

With The Lottery Ticket Eckersberg was in the realm of a popular and unsophisticated genre. He had a broad audience in mind, so the characters in the series had to be instantly recognisable – templates everyone could understand. The cobbler is a naïve, uneducated artisan, the dandy a scheming scrounger, and the daughter an innocent damsel in distress. The pawnbroker also plays his role in the simplest and least ambiguous way: he is ‘the Jew’. At the time the word ‘Jew’ denoted not only those who professed the faith of Judaism, but also pawnbrokers and moneylenders, which is where the confusing Danish term ‘en kristen jøde’ (a Christian Jew) – i.e. a Christian who lent money for interest – came from.50 The word had gathered such widespread negative connotations that in 1813 the Jewish community in Denmark petitioned Frederik VI to no longer be referred to as ‘Jews’. The state authorities accepted the petition, stating that ‘[b]elievers in the Mosaic Faith, who have a civic position in the state administration should, in official issues relating to neither their religion nor its traditions, be designated solely by their position and not by their religion.”51 Subsequently, the words ‘Jew’ and ‘Jewish’ ceased to be used, even in the 1814 decree granting ‘Professors of the Mosaic Faith’ civil rights.52

The Jewish pawnbroker therefore has to be seen as a symbol everyone would recognise so Eckersberg could tell his story as clearly as possible. After 1813 this symbol was laden with far greater political and moral significance, which would have placed Clemens and Eckersberg on the side of the conflict they apparently did not want to be on. Copenhagen did not subsequently experience pogroms as violent as that of 1819, although in 1830 there was tumult surrounding the planting of the foundation stone for a synagogue in the city.53 In his diary Eckersberg wrote that there were disturbances in the street, and that windows had been broken.54

The Lottery Ticket series is among the genre works Eckersberg was interested in during his youth, prior to specialising in history painting, seascapes and portraits. These popular works were a way to make ends meet, but he also found them amusing, and as his correspondence with Clemens shows they were works he was proud of. Eckersberg never lost his fondness for works with a broad appeal. In the 1820s, for example, he painted long prospects that were exhibited in highly popular panoramas, and later in life, in the 1830s, he resumed painting genre pictures in works like En matros tager afsked med sin pige (‘A Sailor Bids his Love Goodbye’).55

Clemens etched several of Eckersberg’s works over the following years, including the more traditional academic genres of portraits and religious paintings. They were professorial colleagues at the Royal Academy from 1818, and their friendship continued until Clemens’ death in 1831. Eckersberg had much to thank Clemens for, both as a friend and mentor. Clemens secured his younger colleague both customers and patrons, and with a minor alteration to a satirical work saved him from a situation which could have been embarrassing and cost Eckersberg connections to the Jewish bourgeoisie. ▢

Translation by Jane Rowley