Summary

Like a colossal, Black mermaid surfacing from an imaginary Black Atlantis, I Am Queen Mary expands the cultural boundaries of the nation-state of Denmark and Danish artistic tradition by insisting that Denmark belongs to the history of the Middle Passage.

Articles

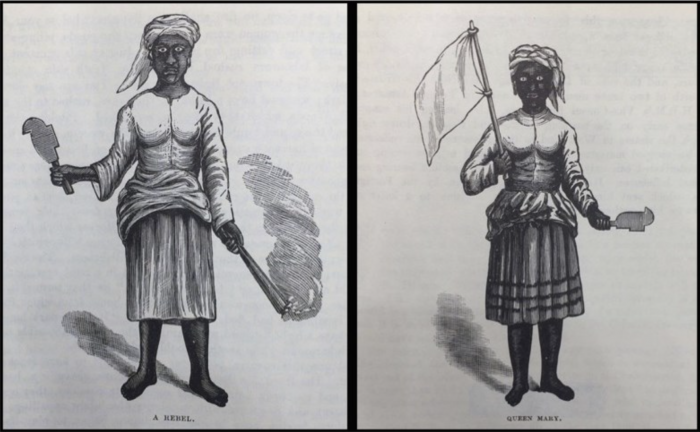

On the same harbor front where the iconic sculpture by Edvard Eriksen (1876-1959) of Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid poses on a rock for tourists, reigns another mythical sea creature. She has surfaced not from a fairytale but from the currents of Afrofuturism, emerging from the underwater underside of the transatlantic slave system as an aquatic cyborg that speaks truth to Danish history. Printed in polystyrene and sprayed with bronze-colored paint, the twenty-three-feet tall statue represents the historic figure of Queen Mary, a Black migrant laborer who worked in St. Croix, one of the three islands that comprised the Danish West Indies [fig.1]. Enthroned in a wicker chair, Queen Mary holds a cane bill and a flaming torch, attributes that allude to the indentured labor conditions in Danish sugar plantations and the 1878 revolt against those circumstances, which Queen Mary co-organized with three other women.

The sculpture was created to commemorate the centennial of the sale of the Danish West Indies to the United States in 1917. The product of a collaboration between Virgin Island artist La Vaughn Belle and Danish-Caribbean artist Jeannette Ehlers, it disrupts the conventional contemporary Danish narrative of equality, tolerance, and welfare. The artists were not commissioned to create I Am Queen Mary: the statue is an uninvited intervention, which, in their own words, claims public space to transform the narrative around colonial histories “by centering the stories and agency of those who were brought to the Danish West Indies.”1 By including and conceptualizing Denmark in relation to the Black diaspora and the Middle Passage, the statue writes Denmark into a history it otherwise distances itself from. But more than offering a “corrective” to Danish history, the statue is a celebration of the legacies of Black resistance on which it builds its conceptual, political, and visual foundation.2

This article situates the statue within this complex traffic of quotations rooted in an imagined Black history and future. Such references include the peacock throne, the title “I Am …”, the use of corals in the plinth, and Queen Mary’s head fabric.3 The article also examines engagements with the sculpture’s iconography in the Danish press, which often denounced the statue as derivative of classicizing representation, thus denying it extensive critical analysis.4 For comparison, the article also presents the statue’s reception in the Virgin Islands. This article builds on pre-existing literature to unfold the statue’s affinity to a large web of Black artistic practices across the Atlantic and is particularly indebted to scholars and art historians Mathias Danbolt, Michael Wilson, and Nina Cramer.5

Foam and Funds

The centennial anniversary of the sale and transfer of the Danish West Indies from Denmark to the United States on the 31st of March, 2017, was commemorated by a range of exhibitions, symposiums, and celebrations in Denmark and the Virgin Islands. As part of the remembrance ceremonies, researcher at Roskilde University, Denmark, Helle Stenum proposed the project, “Warehouse to Warehouse,” that entailed exhibitions at colonial warehouses in Copenhagen and in St. Croix.6 The project included simultaneous displays in both locations with commissioned artworks by Belle and Ehlers. While Stenum’s initial plan failed due to lack of funding, the project proposal initiated a collaboration between Belle and Ehlers. The aim of the germinating artistic partnership was twofold: first, to make visible the enslaved and indentured labor on which Danish wealth and built environment is founded, and secondly, to connect various Black resistance movements and center them on the figure of Queen Mary.

Born in Antigua in 1842, Mary Leticia Thomas migrated to St. Croix to seek work in Danish sugar plantations. Signifying her role as a community leader, Thomas was given the title “Queen” when she co-organized and led the 1878 labor revolt in St. Croix, an uprising against the contractual servitude that bound workers to the plantations after the abolition of slavery in 1848.7 The insurrection, later known as “Fireburn” due to the extensive burning of plantations and the city of Frederiksted, was not an unknown event to the Danish public at the time; it was widely covered in the international and Danish press and also discussed in the Danish parliament.8 Following the insurgencies, Queen Mary was prosecuted; along with numerous other participants including the three fellow “Queens,” Axeline Elizabeth Salomon, Mathilde McBean, and Susanna Abrahamson, Queen Mary was sent to Denmark to be incarcerated in Christianshavn’s Women’s Prison in Copenhagen. Their sentences were later commuted, and they returned to St. Croix.

While several organizations, public and private, supported the artistic project including the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces, the Municipality of Copenhagen, Beckett-Fonden, the WOW Factory, TG Technology, and 3D Printhuset, the project raised far from sufficient money to mold the sculpture in time for the 2017 centennial, and the production of the statue was delayed by one year. Further, lack of funds prevented the artists from casting the statue in the intended material of bronze. I Am Queen Mary is therefore printed in polystyrene foam and sprayed with bronze-colored paint. The troublesome and continuous efforts to fund the statue suggest that Danish colonialism and the statue itself present a challenge to common Danish history narratives. While Thomas long has held a significant cultural position appearing in historical narratives in the Virgin Islands, she has remained unknown to the present-day Danish general public. Only recently has her political organization been given attention, largely due to the artistic, intellectual, and emotional labor of the artists. By choosing Queen Mary as their protagonist, Belle and Ehlers underscore the politics of Danish history and representation.

The funding trajectory of I Am Queen Mary stands in stark contrast to Danish artist John Kørner’s bronze statue of Victor Waldemar Cornelins [fig. 2], which was sponsored by Statens Kunstfond, the public art agency, and the city council of Nakskov, Denmark. Kørner’s sculpture represents the historic figure of Cornelins (1898-1985), who was born in the Danish colony St. Croix and under “unclear circumstances” taken to Denmark to be displayed with his sister in the Tivoli Gardens in 1905. Following Tivoli’s human exhibition of Black people, Cornelins settled in Denmark and became a school teacher and deputy headmaster in Nakskov.9 Claimed as a local celebrity, Cornelins is cast as an example of “successful” assimilation. The biographies of Queen Mary and Cornelins significantly diverge from one another and so do the visual languages with which they are represented: while Kørner deploys a realist visual language, I Am Queen Mary is saturated with symbols and iconographic references to Black artistic and political movements. In contrast to the case of Kørner’s statue, which is permanently displayed by Nakskov train station, no public institution has yet agreed to house I Am Queen Mary. She is an unbidden revolutionary with no commission and funds that unsettles more than reinforces the conventional history of Denmark. In April of 2019, the Copenhagen city council allocated limited funds to investigate the possibility of incorporating the statue into the Copenhagen cityscape.10 As announced on the website of the statue, the artists hope to cast two versions in bronze to be placed in both Denmark and the Virgin Islands, yet the project suffers from insufficient funds.11 For now, the artists seek permission from the Copenhagen city council on an annual basis to continue the display of the foam statue.

Press coverage and analyses of the statue often fail to include the difficulties of realizing I Am Queen Mary and the criticisms it incited among the Danish audiences. Indeed, several Danish news articles and opinion pieces attest to a prevalent white and racist fear sparked by the sight of a Black leader.12 Seemingly, parts of the Danish public are as shocked by Queen Mary’s strategies of resistance as by the conditions that she fought against, accusing the statue of legitimizing violence as a political instrument. Other public reactions, Danish as well as international, include applauding welcomes of the statue as a symbol of Denmark’s liberal history-writing. For instance, the center-left French newspaper, Le Monde, praised the statue as a public Danish recognition of and tribute to the Black Queen, thus focusing on today’s supposed Danish progressiveness.13 However, without exposing the political reluctance towards the statue and the fact that I Am Queen Mary is an intervention into the public sphere, a liberal picture of Danish history writing is conveyed and continued. If the ideological and financial obstacles the artists faced and still are facing are eschewed, the statue risks co-optation into the presentist narrative of progressiveness that in fact excludes or mutes the history of slavery and colonialism.14

Blackness in the Plaster Cast Collection and Copenhagen Harbour

I Am Queen Mary has been noted for its institutional critique of museum and gallery spaces: the statue is located outside the Danish National Gallery’s plaster cast collection of classical and Renaissance reproductions, a collection that since 1984 has been housed in the former West Indies Warehouse.15 Since I Am Queen Mary is intentionally juxtaposed with a bronze replica of Michelangelo’s sculpture David, the sculpture is often read as a successor to classicizing sculptural representation [fig. 3].16

Indeed, the statue appropriates the visual language of statuary and monumentality: placed on a high plinth, Queen Mary is seated on a throne like a reigning monarch, holding a torch, an attribute that evokes other female figures such as Frederic Bartholdi’s late nineteenth-century designs Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia [fig. 4] and Statue of Liberty.

Across the political spectrum, Danish newspaper reviews interpret I Am Queen Mary in continuity of European monuments.17 Rather than recognizing the subversive potential of the sculpture’s appropriation of such visual language, reviewers conclude that the statue lacks iconographic innovation.18 While the statue’s mimicry of European tradition echoes a feminist practice of replicating and thereby subverting the language of the oppressor, the statue is often reduced to a simplistic copy of the classical tradition, for instance, denounced as a poor replica of the National Mall’s presidential statues.19 Such readings ignore the statue’s poignant critique of the very means of representation that it is accused of blindly copying. While art historian Nina Cramer, who worked closely with the artists, has illuminated the sculpture’s attempt to contribute to a Black diasporic aesthetic, the press rarely cited or took into account her writing.20

Printed in foam, indeed unintentionally, I Am Queen Mary presents a monument that not only intervenes in history and disrupts the civilizational monopoly of the West; the statue also defies the classical hierarchy of materials, and further, as Danbolt and Wilson argue, questions the inherent permanence often prescribed to Western monuments.21 The failed fund raising that resulted in a foam sculpture underlines the challenges of recounting the story of Queen Mary in a Danish context.

While some public figures such as Henrik Holm, curator at the National Gallery of Denmark, argue that the statue attempts to broaden the scope of Danish history by allowing differences to exist, art historians and art reviewers generally struggle to engage thoroughly with the artists’ ambition of inserting Denmark into a Black diasporic aesthetic.22 The Danish public aversion to unpacking the aesthetics of I Am Queen Mary is part of a long tradition of denying Black visual practice rigorous analysis: Black art has been denied visual analysis for decades in the field of art history. Thus, Danish journalists and scholars contribute to a pattern of denigrating Black visual practice as derivative and imitative, refusing to acknowledge originality in Black art, holding I Am Queen Mary beholden to arbitrary standards of “authenticity.”23

The artists’ chosen location for the statue by the warehouse not only unsettles the established art historical canon but also critiques the continuous injustice committed within and by the built environment of port infrastructure, a criticism that connects colonial harbor canals with present-day marginalization.24 Located on the harbor front of Toldbodgade 40, Queen Mary faces the Øresund, the sound through which the ships of the Danish West India Company sailed to reach the Copenhagen docks and unload Caribbean commodities such as sugar and rum. The canals house Nordatlantens Brygge, the North Atlantic House, a brick warehouse that stored goods from the Danish colonies of Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. Further down the canal is Børsen, the Danish Stock Exchange, which is ornamented with a sculpture of Neptune, Roman god of the sea.25 Today, the waterfront is undergoing rapid gentrification: to list a few examples, until 2017, a former colonial warehouse housed the well-known Danish restaurant NOMA; in 2005, Operaen på Holmen, the Danish opera, was erected on the island of Dokøen; the island of Papirøen, or Christiansholm, is in the process of being converted into private housing. The chosen location of the statue’s historic intervention thus underlines that urbanscapes are entangled with colonial and imperial practices as well as contemporary exclusion of poor people from the city center.

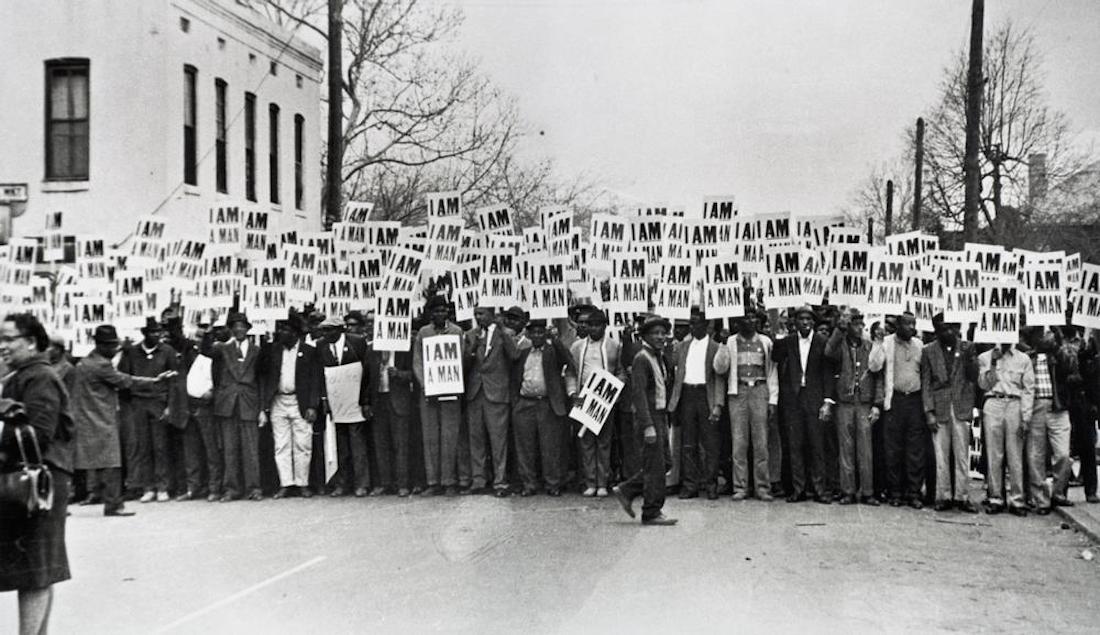

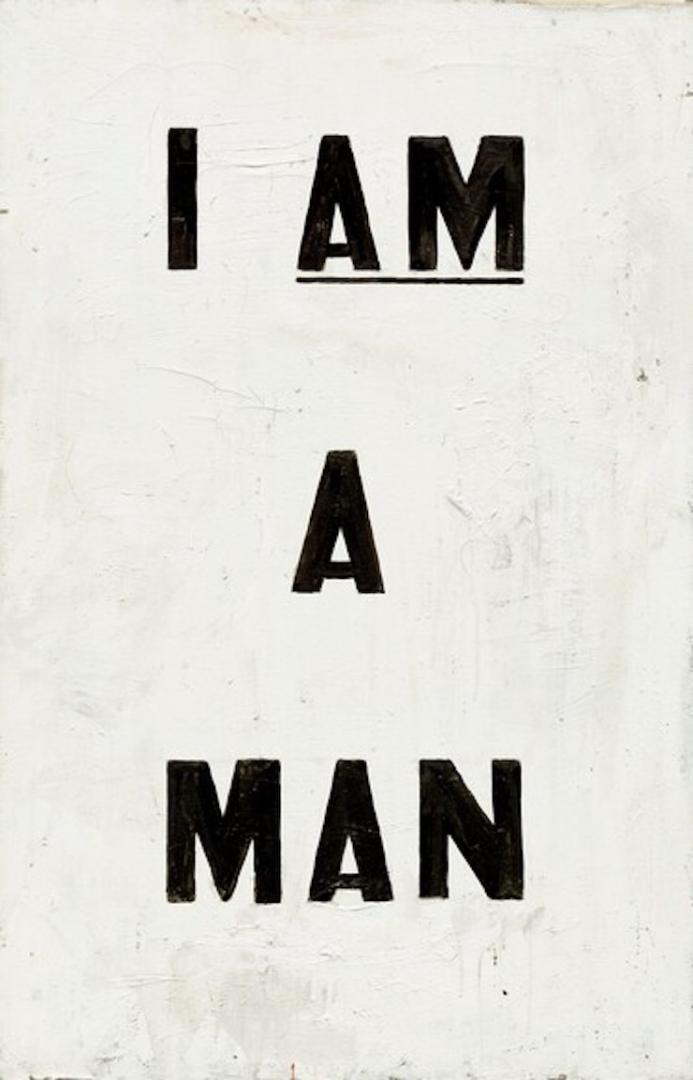

I Am Queen Mary represents a laborer: Queen Mary holds up her attributes – a cane bill and torch – that like her bare feet are symbols that allude to the conditions of working in sugar cane plantations and the coercive labor contracts that she rebelled against. Belle and Ehlers highlight the title’s genealogy of Black laborers’ protests: the title cites the placards from the 1968 Memphis Tennessee sanitation workers’ strike that read, “I Am A Man” [fig. 5].26 By referencing this historic fight for Black workers’ rights, the artists weave together Caribbean anti-colonial resistance in the nineteenth century and American civil rights movements in the 1960s. Further, they inscribe themselves in a long history of Black artistic practice: Glenn Ligon’s placard, Untitled (I AM A MAN) (1988), which also echoes the workers’ strike protest boards, highlights the continuous denial of Black people’s humanity, for instance by referring to Black men as “boy” instead of “man” [fig. 6]. Another instance of “I Am …” is Nathaniel Donnett’s placard How Can You Love Me and Hate Me At the Same Time? (2011), which reads, “I AM A MEME,” a comment on the historic and present reduction of Blackness – and Black suffering – to entertainment [fig. 7].27

As such, the statue’s title engages in a dialogue across time, space, and regimes of oppression. Indeed, the long-term history of Black resistance against racial violence was underlined at the unveiling of I Am Queen Mary when Black Lives Matter-Denmark led a march from the former women’s prison where the Queens had been incarcerated to the statue’s location at the harbor front.

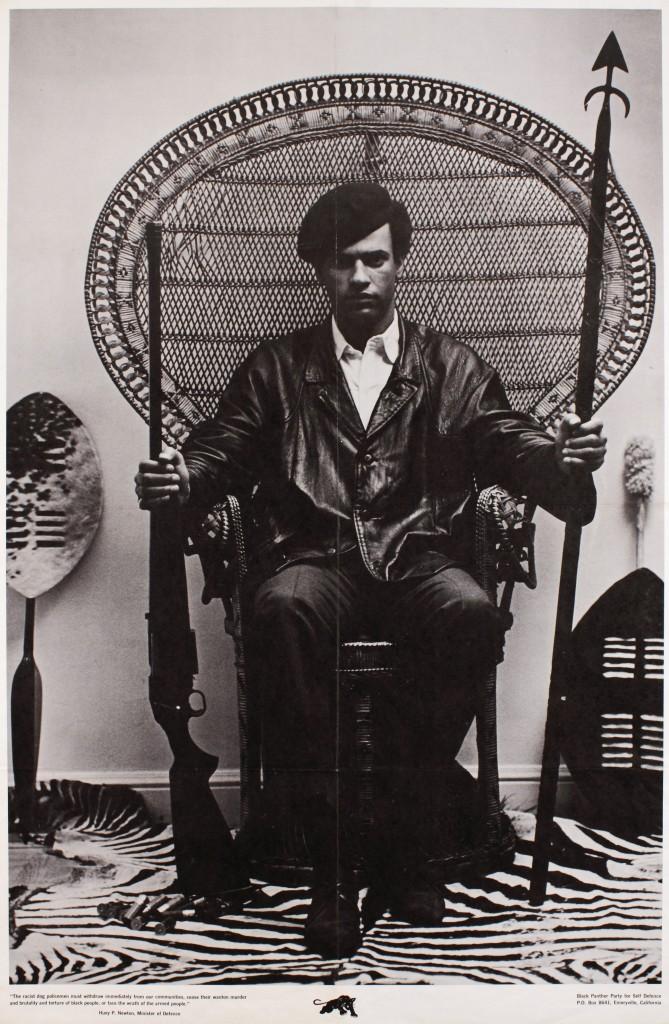

The artists underline the iconographic similarity between artist Blair Stapp’s widely circulated portrait, Huey Newton Seated in Wicker Chair (1967) [fig. 8].28 Enthroned in a peacock chair like Queen Mary, Huey Newton, Minister of Defense of the Black Panther Party, is holding a spear in the one hand and a rifle in the other, flanked by shields, waiting for “the end of violence against Black people,” as stated in the portrait’s lower left corner. The zebra skin rug on which Newton is seated alludes to Pan-Africanism, the idea and movement that aims at fostering solidarity among diasporic Black communities and strengthening ties between the Black diaspora and Black peoples in the African continent.

Similarly, Queen Mary’s headscarf not only echoes laborers’ historic use of cotton headwraps in plantations, but also references the Pan-African cotton head fabric that symbolizes working class affiliation and membership of a global community of Black people.29 Further, the headwrap, the position of Queen Mary’s bare feet, and the attempt to create a colossal monument of a Black woman echo imageries of ancient Egyptian pharaohs.30 By deploying such language of monarchical royalty, the statue alludes to Afrocentric history writing that reclaims Egypt as the cradle of African culture from Western monopoly. Finally, both the title “Queen” and Thomas’ royal representation evokes the notion of a Black Virgin Mary or Queen of Heaven. As such, I Am Queen Mary suggests an affinity to the religious and political movement of Rastafarianism that interprets the biblical exiled people as the Black diaspora and envisions the biblical return as the “homecoming” of Black people to the “motherland” of Africa, more specifically Ethiopia, after exile in slavery.

Birthed from the Ocean

In rewriting the history of Queen Mary and Danish colonialism, Belle and Ehlers faced an archival dead end. In response to this impossibility of knowing the past, the artists employed a collage of references to Black future fantasies in which “homecoming” and humanity are possible. I Am Queen Mary manifests the tension between the inevitable failure of any attempt to represent Queen Mary and the necessity of recounting history. This understanding of history as something that escapes both accuracy and fiction is akin to Saidiya Hartman’s concept of “critical fabulation.”31 Her historical method addresses the boundaries of the archive and the limits of knowing the past: the search for correctives is an impossible quest. The historian’s desire to recount a “true” history ultimately leads to the fetishization of violence and “marginalized voices.”32 Where the possibility of knowing ends, fantasy begins: with its numerous references to Black cultural practices of reconstruction and resistance, I Am Queen Mary offers a speculative representation welded by fragmented historic traces and Black fantasies, thus attempting to modify history while concerned with the limits of historic retrieval, a task that ultimately risks committing further violence by narration.33

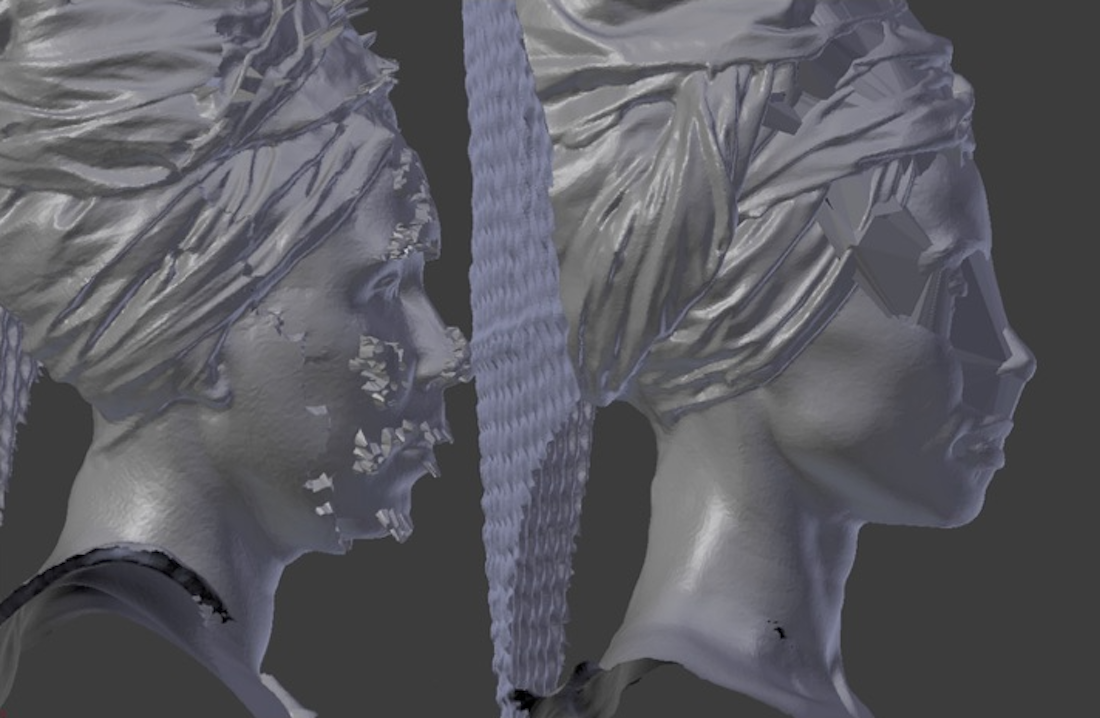

Ehlers states in an interview that her practice is part of a larger movement that transcends national histories: Queen Mary is the symbol of an expanded self that stretches between Copenhagen waterfront’s immediate time and space.34 In line with this effort, Belle underlines that I Am Queen Mary challenges Denmark’s collective memory by being “a hybrid of our bodies, nations, and narratives,” a statement that is repeated in the plinth’s plaque.35 Indeed, I Am Queen Mary is a hybrid that includes a collective of Black women: the left and right sides of Queen Mary’s body are asymmetrically modelled on Ehlers’ and Belle’s bodies; the statue’s facial features are digitally modelled as a fusion of the artists’ features [figs. 9, 10]. As the artists themselves notes, I Am Queen Mary is a “futuristic woman.”36

The statue’s allusions to notions of Afrofuturism present a critique of the idea of Black people not being able to keep up with the pace of high-tech society despite the fact that Black people’s labor historically contributed to technological development and further, that Black bodies served as experimental playfields for this development.37 I Am Queen Mary problematizes the inferior position of Blackness in relation to modernity: conceptually, the statue locates Blackness as a central component to globalization as it developed during the European colonial discovery, conquest, and trade by the end of the fifteenth-century. The statue’s iconography also refers to Afrofuturism: the peacock throne, for instance, appears on the cover of the Afrofuturistic band Funkadelic’s album “Uncle Jam Wants you” (1979) [fig. 11]. While digital futures conventionally are imagined as raceless and bodiless, the statue insists on the Black body as a central component to the future existence, recovery, and healing of the Black diaspora.38

In addition to the artists faces, the statue draws inspiration from a woodcut by the English doctor, Charles E. Taylor, who in 1888 portrayed Thomas as wearing a white headscarf and garments and holding a cane bill and torch, not unlike Belle and Ehlers’s rendition [fig. 12].39 The artists’ decision to rely on and merge their own faces with the doctor’s woodcut evokes the historic European medical desire for and obsession with Black women’s bodies. Perhaps, the most infamous case of such violence was the exhibition of the Khoikhoi woman, Sarah Baartman, who toured with a “freak show” in the UK from 1810-15. Upon Baartman’s death, French scientist Georges Cuvier dissected her “curious” body, which he described as “grotesque.”40 In their recreation of Queen Mary, Belle and Ehlers appropriate the racist “Frankenstein” monstrosity ascribed to Black womanhood.

The “monstrous” hybridization of the bodies suggests a kinship with the “humanimal” aquatic avatars that emerged out of the imaginations of the Atlantic in Black studies. Indeed, the “avatar” is a way of using the body as material for artistic creations to unsettle the objectification and dehumanization of Blackness.41

The Black Atlantis

Famously, The Black Atlantic (1993) by Paul Gilroy presents a theory of culture that highlights the two-way traffic of cultural impulses between motherland and colony; the sea facilitated multiple channels of communication created by the journey across the Middle Passage. Gilroy’s Black Atlantic was absorbed into a Danish context with the collective Kuratorisk Aktion’s conference “Rethinking Nordic Colonialism: A Postcolonial Exhibition Project in Five Acts” (2006) where Gilroy’s contributed with a speech on the Black Atlantic in a Nordic context.42 A conference at Copenhagen University “Denmark and the Black Atlantic” was organized the same year to introduce Gilroy’s framework into research on Danish colonialism. The conference was prompted by Gilroy’s question in The Black Atlantic: “what of Nella Larsen’s relationship with Denmark?”43 Despite this previous engagement with the conceptual framework of the Black Atlantic, Gilroy’s work was generally not applied in Danish analyses to unpack the statue’s multiple layers of meanings.

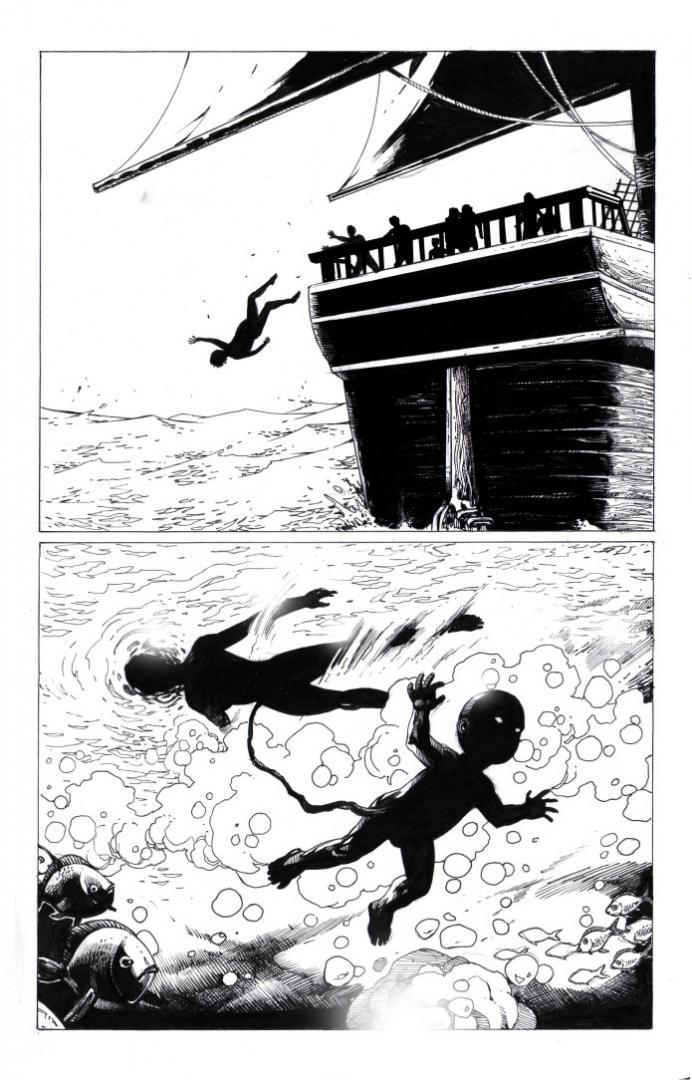

The organizing symbol of Gilroy’s “Black Atlantic” is “the image of ships in motion across the spaces between Europe, America, Africa, and the Caribbean,” ships that assisted in the circulation of ideas and bodies.44 In a constant state of travel, Blackness moves through routes that were initially opened by exploitation, pathways that shaped Black cultural practices and enabled “call-and-response” echoes across the ocean. On the one hand, the Atlantic assisted racial violence and European conquest; on the other hand, it offers a fantasy – a necessity born out of historic elimination – that allows for imagining a different cultural history where the notion of origins is shifted from Europe to the ocean, the space in-between. The fluid and unfixed maritime setting provides a model for conceptualizing mixture and movement through the liquidity of water. The image of the sea insists on a cultural history that “overflow” from the containers of modern nation-states.45 Inscribed by patterns of itinerancy, the ocean holds the potential of reconstructing the history of the Black diaspora otherwise erased on land. Strewn across the bottom of the opaque salt water, lies the traces of slavery – clutters of shipwrecks, bodies, and cargos – that when pieced together speak truth to the violence committed.46

The Atlantic features widely as an artistic imaginary, for instance, echoed in the Detroit techno duo Drexciya, whose music orbits around the speculation of a race of Black sea creatures and heirs to the enslaved people who died at sea. Their album sleeves recount – in text and image – the story of this mythological underworld, a Black Atlantis where amphibious cyborgs dwell [fig. 13]. As such, I Am Queen Mary continues an Afrofuturistic fantasy of an alien environment, be it outer space or the ocean, inhabited by mutated abductees and where time travel is possible.47 The origins myth of Drexciya imagines enslaved people who died at sea resurrecting not as indentured laborers but as strange creatures bred by the sea, as fusions of the sharks that followed the slave ships and the jettisoned pregnant Black bodies.48 I Am Queen Mary is one such example of an impossible and alien reshaping of a lost historic Black subject.49 The statue is an exploration of kinship formation, a kinship that emerges from the Atlantic as a hybrid of the historic figure of Queen Mary, medical drawings, and the artists’ bodies.50

The conceptual centrality of the ocean is reinforced by the statue’s plinth, which is composed of corals. The one and a half ton of corals were initially cut from the Caribbean ocean by enslaved people for the house foundations of colonial officers and plantation owners in the Danish West Indies. The plinth material was sourced from historic houses owned by Belle and shipped across the Atlantic over the course of two and a half months, thus replaying the journey of a slave ship [fig. 14].51 Placed on material harvested from the bottom of the sea, the statue brings into light the constructional foundation of corals that otherwise remain hidden beneath the red colonial brick houses, a symbol of the invisible Black indentured and slave labor that indeed formed the foundation of the metropole’s wealth.52

Reception of Transatlantic Diasporic Imagery

I Am Queen Mary was created partly as an attempt to foster transatlantic solidarity, for instance, by drawing upon Pan-African and Afrocentric references. Indeed, during their three public artist talks in the Virgin Islands, one on each island, Belle and Ehlers received extensive praise from local audiences. In comparison to the Danish press that generally offered hostile misreadings of I Am Queen Mary, Virgin Island audiences compared Belle and Ehlers to Michael Angelo, calling the statue a “masterpiece” and symbol of empowerment.53 The statue inspired audiences to look into family history and use the newly setup online archive “Fireburn Files Network.” Further, I Am Queen Mary started a reflection on who else should be commemorated publicly.54 Locals offered to help raise funds to bring a version of I Am Queen Mary to St Croix, revealing a need and desire to have more monuments of colonial resistance.55 Impressed by its size, the statue sparked emotional reactions and pride in cultural legacy and was welcomed as a long awaited imagery.56

Bringing a similar statue to the Virgin Islands would present a set of challenges. In the Virgin Islands, Fireburn is commemorated already and Queen Mary is integrated into cultural mythology. There would be no need to “push” the Queen into public consciousness and cement her as a historic figure as was the case in Denmark. However, a project in the Virgin Islands would involve an extensive engagement with the Virgin Island community in developing a new iconography of the Queen. As Belle relates, the imagery of Queen Mary is a national icon and using her in a statue would require navigating her pre-existing meanings.57 Indeed, I Am Queen Mary’s appropriation of a pre-existing imagery sparked criticism. The news outlet Virgin Island Consortium noted that the statue was seen as “controversial”: numerous islanders criticized the artists for being “narcissistic” by modelling Queen Mary’s face on their own. Such criticisms also circulated widely on Facebook.58 To some people, the statue was perceived as a historical monument rather than a conceptual sculpture.59

As predicted by Belle, certain critics in the Virgin Islands saw the statue as an appropriation of a local heroine whose meaning was refashioned to be palpable to a Danish white context: the statue appealed to and privileged a Danish audience over a Caribbean one. Rather than building a transatlantic bridge, the sculpture was perceived to establish the dichotomy between “Caribbean” and “Copenhagen.”60 In some cases, Ehlers was perceived as Danish before being Black and the artistic collaboration “Danish” rather than transatlantic. This national positionality raised concern about Denmark once again claiming the islands’ history and “taking” the Queen to Denmark.61

Indeed, the different sides of the Atlantic present different colonial realities and experiences of Blackness, “revealing African diasporic nuances and disparities, differing access to power and privilege, differing ways to think about Blackness and different needs to respond to because of that positioning, with narrative construction being but one of them.”, as La Vaughn Belle describes it.62 Amid praise and celebration, the attempt to gather complex and heterogenous experiences also revealed misunderstandings and discrepancies – that also surfaced between the artists themselves.63 For example, the dichotomizing of race and nationality points to the asymmetrical relationship between Belle and Ehlers: the funding sources were based in Denmark, which dictated the statue’s eventual location. The structural imbalances embedded in the collaboration was not only financial: the unequal footing also required Belle to move her family to Denmark for extensive periods of time. Further, the importance for Ehlers’ to connect with Blackness in the States partly stems from a specific Afro-Danish experience of a search for imagery of Blackness “outside” Denmark as a result of Danishness being defined as whiteness.64 This quest for Black imagery elsewhere is not necessary present in the Virgin Islands. Belle notes in an interview that she did not fully understand Ehlers’ artworks when she first encountered them: Ehlers’ iconography in her work such as Whip It Good (2015) was perceived as a fetishized and problematic image of Blackness.65 To comprehend Ehlers’ work, Belle had to learn about the specific experience of Afro-Danes, in particular, the public denial of the existence of race and people of color in Denmark. The criticisms reveal the challenges of transferring racial categories from one continent to another, from the US, to the Caribbean, and to Europe. While I Am Queen Mary insists on Blackness in a Danish context, the statue also appeals to an invented collective identity that perhaps homogenizes a multiplicity of Black experiences and histories specific to places.

Conclusion

Belle and Ehlers’ I Am Queen Mary inscribes Blackness into the history of Western civilization, not as a mimicry but as part of and intrinsic to the Euro-American tradition. By appropriating the language of the canon in the context of Black political art, the statue distorts and reforges classicizing iconography to assert itself outside and beyond the canon. I Am Queen Mary charts Denmark on the map of “the Black Atlantic” and submits that the colony and the metropole co-created each other: the Black labor union leader Queen Mary is part of Danish history. Indeed, the Caribbean corals and Black Queen that today appear alien in the Copenhagen cityscape belong to the web of Danish colonial exchange. The sculpture I Am Queen Mary is founded on the maritime, diasporic channels of communication created by colonialism, channels that are undeniable as seen in the Copenhagen canals and harbor area well as the bodies of the artists.

Despite the statue’s numerous references to the long history of Black iconography, this lineage has largely been ignored in the analyses and reviews of the sculpture, an act that has allowed for the statue to be appropriated by the conventional, “progressive” narrative of Danish history or to be rejected as “derivative.” Thus, the absence of critical examination denies the statue its full critical potential. Without investigating the visual quotations of Black artistic practice and the textual statements authored by the artists, the statue remains a frail foam echo of classicizing representation.

The statue is founded on a rich intellectual framework that draws upon ideas of Pan-Africanism, Afrocentric history, Rastafarianism, the civil rights movement, and Afrofuturism as well as scholars from both sides of the Atlantic. Through a complex web of iconographic references, the statue’s recovery of the figure of Queen Mary offers a vision of a collective Black fantasy that is concerned with sustaining Black life and shaping Black futures.66 Like a colossal and Black mermaid finally surfacing from the imaginary Black Atlantic, I Am Queen Mary expands the cultural boundaries of the nation-state of Denmark and Danish artistic tradition by insisting that Denmark belongs to the history of the Middle Passage, a history that Denmark otherwise refuses to recognize itself as part of.

Postscriptum

When I Am Queen Mary was cast not in bronze but foam, artists Jeannette Ehlers and La Vaughn Belle expressed concern about the material’s lack of durability: foam is neither water nor wind resistant. Their worry about the material’s longevity was also a concern about the fragility of the statue’s message. The cheaper material of production posed the risk of rendering the meaning as fragile as foam itself.

In December 2020, I Am Queen Mary lost her head to a storm. Of course, the partial destruction reminds us of an artwork’s impermanence, its existence beyond its physical form, and finally, a long history of iconoclasm. More importantly, in the context of the aftermath of the centennial, the now headless Queen speaks to the political struggle that artists and organizers face in their attempts to denounce Danish history of slavery and the current repercussions of Danish colonial exploitation. The decapitated statue stands as a testimony to the wilful inability to see and act upon the violence caused by an anti-blackness deeply rooted in the history of Danish slavery. Since I Am Queen Mary was perceived as a threat to the current historical and nationalist narrative, the artists did not receive appropriate funds and therefore opted for the cheaper and less durable foam.

The loss of the Queen’s head is also a reminder that Black women artists like Ehlers and Belle suffer not only from financial hardship but also are challenged by institutional strategies of “representation” that turn art into symbols of diversity rather than potent means towards liberation. Still, the act of resistance embodied in the making of the statue persists. As writer Lola Olufemi helps us see, the statue is a dream of a future that cannot be controlled.67

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my colleagues, mentors, and advisors at MIT, in particular, Rachel Hirsch, Elizabeth Fox, and Nasser Rabbat.