Summary

The article addresses the artist Anna Syberg (1870-1914) with particular focus on her approach to art as a ‘space of becoming’; one in which an artistic and aesthetic here and now comes into being. The article examines how the idea of becoming can be followed through an analysis of Anna Syberg’s watercolours and her approach to working as an artist. This is done partly by taking a closer look at her reception on the art scene of the time, partly by analysing why and how Anna Syberg worked with flowers and plants as a motif. The analysis highlights how the sketch and sketch-like elements can be seen as an essential part of Anna Syberg’s enduring way of experimenting with the aesthetic expressive power of the work of art.

Articles

As a painter of flowers, Mrs Anna Syberg is a superior artist. A flickering, merry abundance of splendid colour infuses the walls she fills at the exhibition. Her treatment of her ephemeral models brims with gentle love of form, colour and line. She possesses a happy ability to capture the beauty of the here and now, even after scrupulous observations of almost botanical, scientific thoroughness.1

This description of Anna Syberg (1870-1914) is taken from an exhibition review written in 1912 by journalist and author Fritz Magnussen. In speaking of “the beauty of the here and now”, Magnussen paves the way for a very central approach to Anna Syberg’s works: His brief and precise description poignantly sums up how Anna Syberg finds, in flowers and plants, a range of subject matter made up of “ephemeral models”, of organic growth that is ever developing and in motion – from seed and root to shoot and sprout, from bud to leaf and flower. As he points out, Anna Syberg sees her models as more than botanical phenomena to be represented with scientific accuracy. She depicts their immediate presence, the beauty of the plants’ fleeting and vibrant here and now; in Anna Syberg’s works they are in a state of becoming even while they also simply are. This applies not only to plants, but resonates with us as an existential fundamental condition of all living things.2

Taking the quote from 1912 as its point of departure, this article aims at examining how the beauty of the here and now – or the beauty of the moment, as it will be referred to in this context – can be observed in Anna Syberg’s watercolours as well as in her overall way of working as an artist.3 The article examines how Anna Syberg’s approach to art can be seen as a ‘space of becoming’; a place where an artistic and aesthetic here and now comes into being. The concept of becoming can be seen as a process of creation, as something coming into existence and being formed. In this article, becoming will constitute a framework of understanding conceptualised and exemplified by the analysis. The concept will be unfolded by, on the one hand, looking more closely at the reception of Anna Syberg as a participant on the art scene of the time. This will outline an understanding of how Anna Syberg made a career as an artist, how she, so to speak, came into being as an artist. On the other hand, the analysis will unfold why and how Anna Syberg worked with flowers and plants as subject matter, in particular how the sketch and the ‘unfinished’ – that which is still in a state of becoming – can be seen as an essential part of Anna Syberg’s approach to experimenting with the work’s aesthetic expressive power.

The article thus arises from the questions of how Anna Syberg’s works were described and perceived in her own day? And how can the idea of becoming pave the way for a new understanding of Anna Syberg’s watercolours?

A new perspective on Anna Syberg

In 2020, Faaborg Museum presented the research-based special exhibition Anna Syberg – The Beauty of the Moment (20 June – 8 November 2020). The purpose of the project was to take a fresh look at Anna Syberg’s works, for example by shedding light on her use of a sketch-like aesthetic as a deliberate technique and on Vitalist currents in her work; the latter being a perspective not previously linked to Anna Syberg’s work, yet often highlighted in other Funen Painters.4 In relatively recent times, the museum has created various exhibitions, books and catalogues that have addressed the artist’s oeuvre; an exhibition in 1984 and its accompanying exhibition booklet focused on her watercolour technique, and in 1994 the museum outlined the course of Anna Syberg’s life and the circumstances of her work in a book written by art historian Lise Funder based on the extensive collection of surviving letters and photos.5 Overall, there has been a predominant focus on illuminating Anna Syberg’s works through an emphasis on the biographical narrative of her life and her relationship with the other Funen Painters. The exhibition and research project conducted in 2020, from which this article also springs, aimed to reassess the reading of Anna Syberg through close analyses of her works, demonstrating how a modern outlook on images and art is fundamental to her practice. The objective found expression in, for example, the publication’s research-based article “Udkast til liv – Om Anna Sybergs akvareller” (Drafts for life – Anna Syberg’s watercolours) where art historian Rune Gade analysed the sketch-like qualities of the artist’s watercolours, the way her subjects were arranged and how Anna Syberg’s depiction of plant life connects to the realm of the real. In his analysis, he pointed out that Anna Syberg’s watercolours can be seen as being influenced by French Impressionism’s favouring of the immediacy of the sketch, its energy and vibrancy.6 When comparing her work with flower painting up through history, Anna Syberg’s watercolours can be seen as significant contributions to a renewal of the genre; they are depictions of life, liberated from the genre’s traditional use of illusionism, allegory and memento mori. Gade writes: “Anna Syberg treated her floral subjects with a distinctly modern sensibility and an idiosyncratic ability to convey, through the medium of watercolour, the subtle but uncontrollable vitality of flowers and plants.”7 Another point also highlighted in Gade’s text concerns how flower painting was historically inscribed in an academic ranking of art genres where flower painting was not only consigned to the lowest rung of the hierarchy but also associated with the female gender and thus further devalued.8 From the end of the century until the beginning of the twentieth century, these classic genres and their status were undergoing processes of change and dissolution. In the generation before Anna Syberg, several artists – both men and women – had worked extensively with flowers as their subject matter regardless of the prevailing academic ideals, with examples including the French artists Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) and Claude Monet (1840-1926), who enjoyed great acclaim for their treatment of the flower as artistic subject matter. Their practices and those of other artists influenced the general perception of flower painting, especially in French art and art theory. But to what extent did this genre hierarchy prevail on the Danish art scene, and what significance did it – and the question of the artist’s gender – have around the turn of the century?

In this article, the analysis of the artist’s reception history is elaborated upon by including reviews of Anna Syberg’s exhibitions. They are relevant here because they show how the gendered value assessments of the genre hierarchy still informed the Danish daily press and its coverage of art aimed at the general newspaper reader. At the same time, the approach serves to highlight how contemporary observers would, despite such embedded structural gender discrimination, in several cases appreciate and see Anna Syberg’s watercolours as distinctive works of art, describing them as “alive”.9 The following analyses will delve deeper into Anna Syberg’s use of sketch-like elements. The article will thereby contribute to a nuanced understanding of her original use of the technical and aesthetic traits and devices specific to watercolour.

The early reception

From 1898 to 1910, Anna Syberg exhibited at the juried Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition every year. She returned in 1913, which would be the last exhibition she attended before she died in 1914. When she made her debut at the 1898 Spring Exhibition, she received attention in an art review of the exhibition, which was divided into sections by genre. Flower painting was addressed as a separate category:

It would appear that painting flowers is falling out of fashion altogether. Pictures of the garden’s abundant splendour cut and picturesquely arranged are neither as numerous nor as good as before. Of course, there are exceptions. Harald Holm, who clearly does not consider the painting of flowers below the dignity of menfolk, is probably the one who makes the most of the subject in his magnificent ‘Yellow Chrysanthemum’, ‘Asters’ and ‘Begonia’, all of which are strikingly fresh and full in their colouring. Holm has an especial knack for making reds and yellows appear with great impact. Peculiar are the two flower pictures – watercolour drawings – by Anna Syberg. They were sold immediately. Presumably the painter is married to the painter Syberg, who exhibits at Den frie Udstilling, for there is an overly conspicuous resemblance between the two artists’ technique, crisp, fine lines and thin, clear colours, for this resemblance to be due to pure chance.10

To a present-day reader, this quote is an excellent example of how flower painting was, in a Danish context, still deeply inscribed in a gendered genre hierarchy where painting flowers was associated with femininity. What is more, Anna Syberg’s works are compared and contrasted to her husband’s, which was also the case in other reviews.11 When pointing out the relationship between the two, critics would either praise Anna Syberg for her special way of portraying the beauty of flowers, as distinct from Fritz Syberg,12 or her achievements would be played down, seen as imitations and undeservedly put in the shadow of her famous husband.13

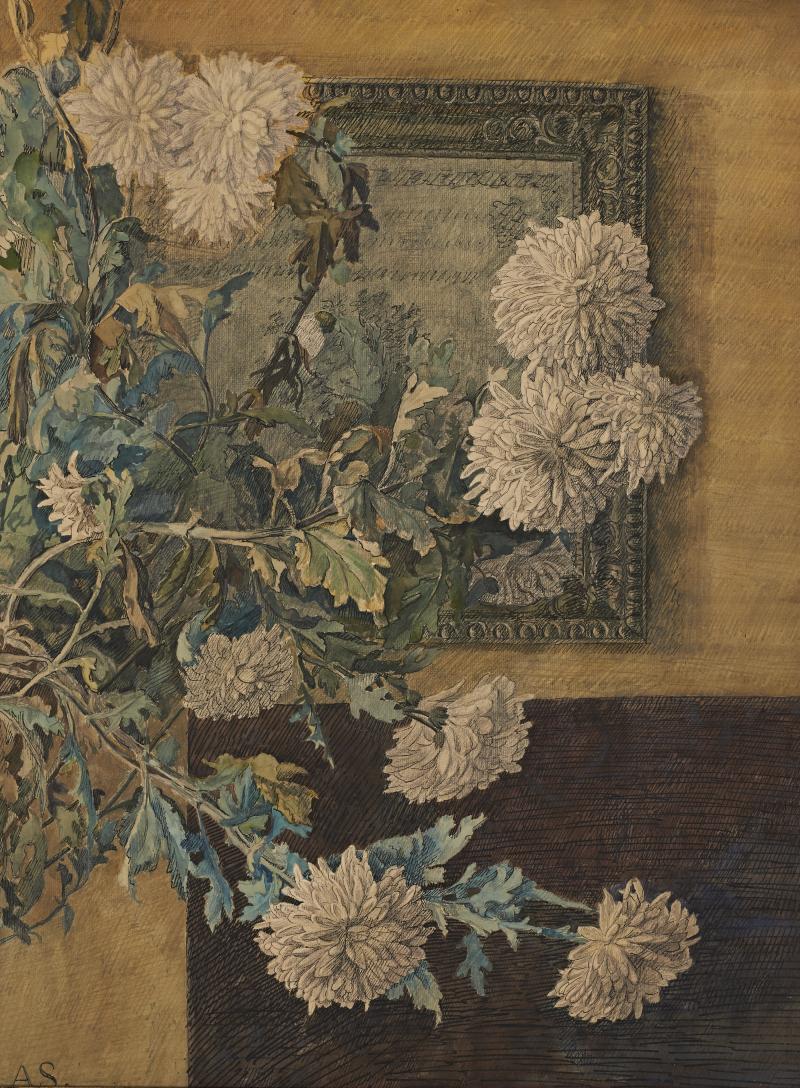

At the Spring Exhibition in 1898, Anna Syberg sold two watercolours: Chrysanthemum, 1898 [fig.1] and Crocus, Hyacinths and Tulips, 1898 [fig.2] to the art collector Heinrich Hirschsprung, who later founded The Hirschsprung Collection in Copenhagen. That same year, she also received DKK 100 from a grant (‘The Exhibition Fund’s Study Subsidy’) awarded by the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Thus, 1898 was the year in which Anna Syberg entered the public sphere as an artist, distinguished by official recognition from the art academy’s grant committee and by her sale of works to a prominent art collector.

A distinctive trait of the two works sold at the exhibition concerns Anna Syberg’s approach to cropping her chosen subjects. Chrysanthemum, 1898, is an interior scene in which a chrysanthemum plant grows organically into the image. Entering from the left, the plant takes over the pictorial space with large flower heads extending into the space, dominating and blotting out the background, which forms a stark contrast to the soft movement of the living organism: It is constructed out of two angular rectangular shapes, one of which is a picture frame containing an image that remains indistinct. The main motif of the image is this unruly growth of the plant. The same approach is evident in Anna Syberg’s Interior with Chrysanthemum from 1905 [fig.3]: Here, too, the plant forms a border zone between an external world, in this case accentuated by the windowsill along which the plant grows, and an interior space, a living room interior taken over by the plant. The second work sold to Hirschsprung was Crocus, Hyacinths and Tulips, 1898, which shows an array of the flowers mentioned in the title: Two hyacinth flowers grow in a pot, while a multitude of mixed flower bulbs have sprouted and bloom from a series of plant boxes, the rectangular shapes creating intersecting lines in the pictorial space. A glimpse of soft curtains and a flowerpot indicate a window setting, hinting at the interior in which the plants are placed, but nothing in this pictorial space can be seen and grasped in its entirety: Pots and plant boxes are cut off, and the plants grow upwards and into each other, cropped by Anna Syberg’s orchestration of the subject on paper.

Such dynamic croppings, which are also found in watercolours such as Wild Roses, 1898 [fig.4], Grapes in a Greenhouse, 1903 [fig.5], Cactus from the Hothouse of the Botanical Gardens, 1908 [fig.6] and Lemons, Pisa, 1913 [fig.7], are a recurring trait in Anna Syberg’s works. It was noted in reviews, too, for example in 1915: “What distinguishes her particularly is the innate sense for the picturesque with which she places flowers in the space so that they fill it, deepen it, live with it […]”.14 Throughout her artistic endeavours, Anna Syberg alternated between plein-air painting, where she found and painted her flowers in nature, and the more classic arrangements of potted plants and cut flowers in vases. Traditionally, arrangements of the kind used in flower painting have been considered still lifes or nature morte, but with Anna Syberg’s modern approach, something more akin to the imperfect, wild nature of outdoor life is incorporated in domestic arrangements, making the houseplants and bouquets seem particularly alive in their indoor settings. The description of how Anna Syberg’s flowers fill, deepen and live in the space and with the space is in line with the French art critic Théophile Thoré’s (1807-1869) critique of the French term nature morte: “There is no such thing as dead nature!” he wrote back in 1860.15 In his article, he emphasised how flower painting should not be seen as a representation of death, but as a depiction of the flowers’ constant movement and their connection with all that lives:

Flowers are not ‘nature morte’. There is no such thing as a ‘nature morte’. Everything is alive and moves, everything breathes in and exhales, everything is in a constant state of metamorphosis. Everything takes or gives something around itself, altering its surroundings as well as itself with irresistible persistence. Everything communicates with everything else and participates in the unity of life.16

Unfashionable flower painting becomes modern art

Over the years, Anna Syberg’s contributions to the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibitions received very little publicity. Not until 1912 and again at her death in 1914, as well in connection with the memorial exhibition arranged in 1915, did the art critics consider her work in any great detail.

In 1912, Anna Syberg lived in Pisa with her family but took part in an exhibition at Den Frie in Copenhagen alongside Alhed Larsen (1872-1927), Christine Swane (1876-1960), Cathrine Svendsen Engel (1877-1949), Karen Meisner-Jensen (1873-1958) and Olga Meisner-Jensen (1877-1949).17 The press dubbed the exhibition “Six Women Artists or The Funen Girls”, even though neither Karen Meisner-Jensen nor Olga Meisner-Jensen were residents of Funen. The show received considerable coverage in the newspapers:

The exhibition encompasses no less than 286 paintings, studies and watercolours, offering a full and lively impression of the stout energy and indisputable talent with which the distaff side of ‘the Funen School’ assert their place next to its men. The exhibition, which will hold particular allure for all who adore flowers, deserves to be richly visited.18

Several reviewers noted that Anna Syberg had long “enjoyed a deserved reputation” for her works presented at the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition,19 and she was praised as a flower painter: “[…] indeed, I think I may claim without exaggeration that among all living Danish artists, she is the one who most beautifully knows how to reproduce the living, natural grace of flowers.”20

Although comparisons with the male Funen Painters came naturally to the critics, the extensive display of the artists’ works also prompted some to describe traits they regarded as particular to Anna Syberg and the other participants:

In all of them, one discerns some influence from their spouses, brothers, brothers-in-law and friends. Being married to Fritz Syberg, one would imagine Mrs Anna Syberg to be particularly prone to this. However, in the flower pictures that have made her one of the most captivating exhibitors at Charlottenborg, she has shown a commendable courage to commit impressions of beauty to the canvas. […] They all have talent, a talent that would yield even richer fruit if they dared to give in to the urge for beauty that reveals itself time and time again.21

In this review, Anna Syberg’s watercolours are praised and assessed on the basis of a concept of beauty that values the naturalistic and detailed representation of reality and the immediate, natural and picturesque beauty of the flowers. At the time, this perception of beauty was being challenged by a new and modern outlook on art, one which reviewers saw amplified in the watercolours Anna Syberg created while in Pisa in the years 1911 to 1913. She exhibited a selection of these works at Den Frie at the 1912 exhibition, her technique very clearly revealing her efforts to offer up modern renditions of interiors and flowers as subject matter, for example in From the Living Room in Pisam Carisima, 1911 [fig.8], which was – as a case in point – criticised for moving away from the conventionally beautiful. As one reviewer stated in Nationaltidende:

In one particular picture, she [Anna Syberg, ed.] has further distanced herself from what seemed to her conventional, employing a manner also occurring in one of the other painters, Mrs Swane [Christine Swane, ed.], one which might be termed ‘the worn manner’ insofar as the colour seems to have been scraped off, revealing the canvas in stripes and peeling flakes. The procedure seems quite pointless.22

What the reviewer mistakenly calls canvas is in fact the paper that Anna Syberg chose to work with in Pisa.23 The type is coarser in its surface structure than usual, and she uses watercolour paints applied predominantly in dry strokes, letting the white, rough texture of the paper shine through notably. In the work, the clear colours flicker against the whiteness of the paper, which will, in watercolours, necessarily stand out as the brightest points in the image. The paper acts partly as a highlight that accentuates and shapes the play of light in the surface of the objects, such as in the vase on the table in the living room, partly as a way for light to penetrate the image and create a tactile sense of the light’s atmospheric presence in the room. The paper also plays a prominent role in works such as Wisteria. Pisa, 1912 [fig.9]: Here, Anna Syberg uses the white surface of the paper to build up the sense of form and space. In the picture, cut branches taken from a flowering wisteria are loosely arranged in a white clay jug. Clusters of blue flowers fall heavily, yet are depicted with effervescent lightness in a variety of rapid, watery brushstrokes of blue. In some places the colour is rendered more intense, and especially around the opening of the jug some of the individual flower clusters are more clearly outlined as the artist has used black ink to outline the contours of the flower petals. To the right, a multitude of flowers gradually fades out because the colours have been applied with a brush mixed with increasing quantities of water. The flowers dissolve as the blue pigment is increasingly diluted, causing parts of them to instead appear as paper-white silhouettes against the solid brownish painted background – a distinctive approach that Anna Syberg also used in her very early works, and which will be elaborated upon in the following sections.

The year after the exhibition at Den Frie, Anna Syberg chose to also submit and exhibit From the Living Room in Pisam Carisima, 1911 at the Danish Artists’ Autumn Exhibition in 1913. Here the picture was once again highlighted in a review of the exhibition, and this time her painting technique was compared to canvas embroidery:

Left is the extraordinarily talented Anna Syberg with her delicate, lightly executed watercolours; incidentally, in her ‘Living Room Picture in Piza’ she has reached such levels of frugality of colour that the result seems restless, almost reminiscent of a piece of canvas embroidery only just begun, its colours and patterns hinted at in a thin thread – and finally Christine Swane, whom we would recommend looking to Anna Syberg to learn a love of nature and an earnestness in the study of the substance and colour of flowers, to avoid any further outcries of bewilderment from the beholder: ‘is this supposed to be flowers?’24

Here Anna Syberg’s experimental watercolour technique is explained through a comparison with handicrafts, a realm also considered a distinctively female sphere at the time and one that ranked below the standards of fine art. In this sense, the assessment can be said to involve a devaluation of the work or perhaps rather a blindness to its modern mode of expression. Yet at the same time, Syberg is highlighted as an example to be emulated, unlike Christine Swane, who in the same breath was criticised for her modern and abstract approach to flower painting. Paradoxically, the reviews alternate between praising Anna Syberg for adhering to a conventional understanding of beauty and criticising her for challenging that very same outlook in her work with different painting techniques and formal approaches in her treatment of watercolour as a medium very different from oil painting.

Choosing the life of an artist

Several art critics and writers on art proclaimed Anna Syberg the best flower painter of her day, for example in connection with her death in 1914 and the memorial exhibition at Kunstforeningen in Copenhagen in 1915:

Her sudden death last summer was a great loss for Danish art. It may be reasonably said that among the few women painters of our time who have had the urge and courage to cultivate the depiction of flowers as a specialty, there are none who equal her in terms of earnest feeling, naturalness of expression and deft, assured mastery of the difficult technique of watercolour. Indeed, there are none whose manner of painting resemble hers.25

The idea of courage offers a useful starting point for understanding why Anna Syberg engaged with flower painting, an art genre subjected to rather dismissive treatment in contemporary art criticism. Why did Anna Syberg choose watercolour as her primary medium and flower painting as her genre? How did working with these aspects constitute an artistic space she could define and renew?

We know very little about how Anna Syberg saw her own works and her endeavours as an artist. Still, the surviving source material and letters allow us to form some insight into how she viewed life as an artist. She grew up in a home that became a cultural and social gathering place for several of Faaborg’s young artists, the Funen Painters, including her brother Peter Hansen and the house painter apprentice Fritz Syberg, who worked for her father, Syrak Hansen, and whom she married in 1894. Syrak Hansen was a prominent and recognised master painter and decorator, giving Anna Syberg direct access to learning the art of decorative painting. From 1892 to 1894 she worked at The Royal Porcelain Factory in Copenhagen where she painted the factory’s popular floral designs onto porcelain.26 In the time leading up to their wedding in 1894, Anna Syberg wrote letters to Fritz Syberg in which she expressed her ideas about the life they were to live together:

I want to go hunting with you when we get married and are to live our lives in the wilderness; don’t you think I’ll be able to learn to fire a gun? You have made me a little scared of the gun, but I’m not afraid of the boat, I’ll certainly learn to manoeuvre that. I have thought about what fun it would be to go on a long trip in one’s boat, sailing from town to town for eight days or so, taking on provisions once in a while, and cooking over a primus stove.27

These ideas are informed by a distinct yearning for freedom, and in several regards Anna Syberg broke away from the roles traditionally assigned to women at the time. She wanted to acquire skills far removed from the housewife’s usual responsibilities, instead being associated with basic survival; hunting, being in nature and not least being free to set off when the opportunity arose.

After their wedding, Anna and Fritz Syberg settled in a rented house in Svanninge near Faaborg. Here they set up a life orchestrated to facilitate the freedom to travel as well as a family life with a growing number of children. They did not strive for material abundance, but to keep a frugal, financially undemanding household that gave them the freedom to simply be, enjoy life and work as artists.28

According to Anna Syberg, finances should not be an obstacle to having an artistic career, a view she expressed in a letter to the friend, painter and art writer Ernst Goldschmidt (1879-1959):

How in the name of Heaven can poverty prevent you from painting? Surely it ought to force you to do so? As long as you have 10 øre for oatmeal, you have four hours at your disposal until hunger strikes again, and you can use that time to generate new value to pay for another meal. If you cannot afford a model, then paint without a model, but paint something, paint something bad if you cannot paint well, but do not be parsimonious with your talent.29

The statement suggests an idealised view of bohemian lifestyles, and it should be mentioned that Anna Syberg came from a middle-class background bolstered up by the social and financial security of a family network, unlike her husband Fritz Syberg, who grew up in poor conditions and whose mother died in a workhouse in Faaborg. Anna Syberg’s letters from her youth contain several examples of a few lines describing how money has had a certain impact on the household, but that this would not be allowed to prevent them from enjoying life and choosing a career as artists with all that this entailed in terms of fluctuating income.30

Having servants to help with the household and caring for the children was a financial priority for the Syberg family. During a summer stay in Sweden, Båxhult in 1900, Anna Syberg did the watercolour The Children’s Nurse, 1900 [fig.10], one of the few figure scenes known from Anna Syberg’s hand. At first glance, the work oscillates between being a drawing and a watercolour. The subject chosen is the nanny with a small child on her lap, rendered in detail on paper in pencil. Offsetting two secondary colours against each other – orange and green – the nanny’s orange-golden hair has been coloured in, as has the upper part of her green dress; the child’s eyes have been coloured blue. The figures are the main subject, and yet they recede partly into the background because Anna Syberg has, in her application of watercolour, focused on the table and its central arrangement of blue flowers in a large brownish-orange pot. On the right side of the paper are smears of excess colour wiped from the artist’s brush and a quick sketch of the child seen from the side. Like the child on the lap, this child is also shown in motion, its movements emphasised by the quickly and loosely outlined little legs and arms. On the left side are traces of watery drips from the brush. Both sides emphasise the sketch-like qualities of the work, and both sides were retained as part of the work when it was framed.

A recurring narrative underpinning art history’s reception of Anna Syberg’s works asserts that in several of her works she displayed uncertainty in her execution31 or that, being a mother and housewife, she was regularly interrupted by children and domestic obligations, meaning that her position as a woman limited her opportunities for artistic expression – an assumption that in part still prevails today as a framework of interpretation.32 Anna Syberg’s artistic work would most often have taken place in brief, intense pockets of time rather than over the course of an entire working day, with the possible exception of the times spent in Copenhagen where she found a workspace in the city’s greenhouses while Fritz Syberg took care of the home and the children.33 But if Anna Syberg’s work with watercolour was about capturing and depicting the presence of the moment, such interruptions were not necessarily obstacles to her artistic project. This holds true of her depictions of the vibrancy of fleeting plant and flower motifs – their here and now – and of her few figure scenes, such as The Children’s Nurse, which precisely captures and accentuates an everyday moment in which the child has briefly sat in its nanny’s lap. Seen from this perspective, interruptions and sporadic work hours become a fundamental condition imbued with a rewarding and positive driving force, one in which the circumstances of life have become an amplifying aspect of a deliberately sought-out mode of artistic expression.

Sketch-like elements

Some have seen the sketch-like aspect of Anna Syberg’s works to mean that they were not worked through, that they never progressed from the sketch stage to become finished works.34 The media of drawing and watercolour were often used to sketch out ideas or as reference materials to assist a further processing of the subject matter, for example in the form of an oil painting. Seen from this perspective, the sketch plays an important role, but primarily during the initial and preparatory phase of the work and as part of a process of creation that was to culminate in the final work of art.35 During the second half of the nineteenth century, the general outlook on the sketch began to change; sketches were no longer used only as studies and for preparation but as works of art in their own right.36 Indeed, Anna Syberg’s watercolours are not preliminary studies for other works, and given that the sketch element appears throughout Anna Syberg’s oeuvre, it may also be seen as a device deliberately used by the artist – a distinctive visual quality to her watercolours as independent, finished works in line with a new conception of art. Seen from this perspective, Anna Syberg’s use of sketch-like qualities can be regarded as an important artistic approach that extends across form, technique and meaning. In one of her earliest known watercolours, Hyacinths from 1894 [fig.11], three hyacinths stand in a row, shooting up from nothing – a space marked only by a horizontal line, a fold in the paper indicating the point of origin of the plants. Leaf growth and flowers are outlined in pencil. Colour has been subsequently applied in shades of green and blue, while the white flowers are given form by lines done in pencil on the white paper. The background is only partially indicated by layered washes of colour; the pictorial space remains abstract. The plants appear as if having risen out of nothing; a moment of protruding growth taking over an undefined space. In pencil, Anna Syberg has added a note on the right-hand side of the paper: “My first attempt at watercolour”. With this pencilled-in inscription, the hyacinths are connected with a specific time: A moment in 1894 in which Anna Syberg articulates her artistic action in words, pinpoints a moment in time from which she now works with watercolour. Given that Anna Syberg did in fact work with watercolour prior to this, the sentence cannot be regarded as a historical testimony to an artistic career beginning precisely with this work.37 However, the inscription does highlight a deliberate action, a moment of heightened awareness of working with watercolour; of painting and being an artist on the basis of a medium used as a vehicle for attempts, for experimentation, for an exploratory approach to art. Fourteen years later, Anna Syberg tried to sell the work, and her letter to the art dealer Martin Arnbak in Copenhagen in 1908 testifies to her awareness of the art market of which she was part:

Mr Art Dealer Arnbak! Unfortunately, I do not believe I have anything to suit the connoisseur at the moment, but I might be able to produce something in the course of some eight to fourteen days as I happen to find myself in the ‘mood’ for exactly that sort of thing. I have some old watercolours lying around, which I also send to you: My first attempt at watercolour, for example; do you not think the connoisseur might go for that? Respectfully, Anna Syberg.38

The watercolour was acquired for Faaborg Museum in 1915 in connection with the major memorial exhibition held in honour of Anna Syberg at Kunstforeningen in Copenhagen. Photographs taken at the museum in 1921 show the work hung in the bay dedicated to the museum’s collection of her watercolours [fig.12]. The photos also show The Children’s Nurse, as well as the watercolour Campanula from 1910 [fig.13], which, like Hyacinths, was part of the acquisition made in 1915. As in Hyacinths, the slender campanula also emerges out of nothing. Bearing distinctive blue, bell-shaped flowers, the plant reaches out across the paper. The flower is partially painted in washes of watercolour, outlined in strokes of brown, green, blue and ochre. The shape is partly marked out by soft but defining pencil lines that elongate and support the painted brushstrokes and transparent layers of colour. A background is indicated by fields painted in watery washes. The brown colours create a sense of space in the image, shaping parts of the flower, enclosing flower buds that, as in the case of Wisteria. Pisa, form white paper silhouettes reminiscent of fleeting, transient shadows, almost hovering in time and space. The watercolour is executed to perfection in terms of technique and image composition, while the imperfect sketch-like qualities introduce contrasting notes that create movement and life in the scene: In a manner of speaking, the growth of the plant remains unfinished, unlimited, in a state of continuous unfolding in so far as the depiction itself seems unfinished due to its sketch-like nature. The flower’s will to live, its becoming, can be said to resonate in the creation of the image itself due to the inherent qualities and impact of the sketch.39 In that sense, it is not the plant, the campanula, that constitutes the subject of the painting, but its movement and continued growth.

As a medium and technique, watercolour differs greatly from oil painting, partly by relying on the untouched, blank paper to act as highlights, and partly due to the transparent quality of the washes of colour. In an oil painting, the canvas and any pencil sketch outlined upon it disappears under its many layers of thick, saturated paint, while changes can be made and flaws amended by any number of overpaintings the artist might wish to do. By working with watercolour, where corrections cannot be done through overpainting, Anna Syberg exploits the medium’s potential to produce an immediate and undisguised here and now insofar as all parts of the work’s creation – its becoming – remain visible; the pencil drawing, the colour washes and, in several works, a contour line drawn with black ink. The growth of the plants and their own stages of becoming as living organisms are thus accentuated by the distinctive openness and transparent nature of the watercolour and the drawn line. As art historian Norman Bryson points out in his article about the distinctive quality of drawing compared to painting:

If painting presents Being, the drawn line presents Becoming. Line gives you the image together with the whole history of its becoming-image. However definitive, perfect, unalterable the drawn line may be, each of its lines – even the last line that was drawn – is permanently open to the present of a time that is always unfolding; even that final line, the line that closed the image, is in itself open to a present that bars the act of closure. There is a final line, but the time of closing the image into a product, in the past tense, over and done with – that time of finally ending the image never fully arrives.40

Like the drawing, Anna Syberg’s watercolours contain this unfinished connection with time. In Anna Syberg’s works, such temporality is an essential part of the experience of the work; the first brushstroke and the last are present at the same time. As our eye slides across the image, the work vibrates between pencil drawing and the pictorial qualities of the watercolour, between beginning and end, between past and present. Attention is drawn to this temporal aspect and thus also to a conscious experience of time and presence, an exchange between work and viewer in the moment of observation.41

With the sketch-like element, Anna Syberg thus experiments with the aesthetic expressive power of her work and with the viewer’s ability to empathise in a refined balancing act poised between the unfinished and the perfectly done.

Thus, the sketch-like feel constitutes a prominent device in her work, as does the repetition of certain subjects. In selected scenes of roses, flowering apple branches, bugloss and stocks, repetition can be seen as a way of exploring different stages of expression inherent in the same subject. In 1912, Anna Syberg painted two watercolours of stocks in Pisa, employing compositions where the plants are located in the same place; the broad, vigorous stem grows up from the lower right-hand corner of the paper; staked and tied up, the plant stretches upwards to unfold in a profuse abundance of flowers and leaves. In one watercolour [fig.14], the plant is surrounded by shades of brown, red and blue. The flowers are accentuated against the darker background. In the foreground, several contours are outlined in black ink, and among the many green leaves the black line creates depth by highlighting parts of the leaves. The second watercolour [fig.15] dates from the same year. Less saturated in colour, it shares the same character as the watercolour Wisteria. Pisa, 1912. Here, too, clusters of flowers fade out into a background that is only lightly coloured, imbued with limited perspective depth. Likewise, a few flowers and leaves have been outlined in pen, but the ink lines are less prominent, taking on a sketch-like effect of their own. The repetition shifts the focus away from the subject matter as meaning-making, instead focusing on how the subject opens itself up towards working with matters formal, methodological and technical.42 In the case of Anna Syberg, these aspects concern how sketch and watercolour techniques can be used to create a powerful, aesthetic now.

The spaces of becoming

Anna Syberg built herself a life as an artist based on modern ideals of freedom, working on her art concurrently with building a family of seven children with her husband, Fritz Syberg. In her works, she insisted on trying out and experimenting with watercolour as a medium and with flower painting as a genre.

Being a woman and working as an artist took courage, and if we follow the critics’ way of thinking, it also required courage to pick up an underrated genre and using it as a vehicle for securing one’s artistic breakthrough. By positioning herself so consistently within the flower genre, Anna Syberg did not compete with genres still favoured in her time: large figure scenes and landscapes done in oil. Instead, she worked around the conventionally prestigious and male-dominated genres. As an artist, Anna Syberg thus placed herself within a broader movement in European art where hierarchies were growing increasingly blurred, as were the divides and relative status between sketch and finished work. In other words, Anna Syberg’s full focus on the lower-ranking genre of flower painting enabled her to conquer it, renew it and use it to create and define a space for her own practice and for her artistic endeavours to depict becomings, vitality and the beauty of the moment. Whether this also applied to other women artists of the period might be usefully examined in a broader analysis of women artists’ choice of media and practice, which often resided in the borderlands between crafts and the classic formats of fine art.43

As will be apparent from the quotes selected above, the contemporary reception of Anna Syberg’s works occupied a territory where a conventional concept of beauty inscribed in a long tradition of flower painters intersected with a more modern and formal approach to watercolour painting that focused on materiality, colours and technique, aesthetic devices and the process of becoming-image. In doing so, she had a kinship with the next generation of painters, such as Christine Swane and Harald Giersing, who were also associated with the circle of Funen Painters through family ties, and who now stand as central artists within Danish modernism. Examining such connections to modernism would be obviously relevant, as would exploring how the vitalistic element of becoming, as conceptualised in Anna Syberg’s works, can be seen in the broader context of Vitalism in art during the period around 1890 to 1940.44

Taking the idea of the here and now as an overall approach to Anna Syberg’s works and artistic practice, illuminating the creation and becoming of this now on several levels, paves the way for an understanding of how Anna Syberg’s opportunities for working with her art and forging a life as an artist while also being a woman and a mother influenced her approach to creating a distinctive artistic mode of expression. Anna Syberg’s works remind us of how the circumstances in which we live and the life that surrounds us at all times is a co-creative force that influences what we do – and the beauty it is possible to create in the moment. This holds true in the creation of Anna Syberg’s works – their becoming – but is also an inherent trait embedded in the subject matter where the process of becoming constitutes an aesthetic statement that remains vibrantly alive and present for us today.