Summary

In 1935 Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen curated the International Art Exhibition Cubism = Surrealism at Den frie Udstillingsbygning in Copenhagen. Based on studies in archives the article discuss the significance of the exhibition and the status of surrealism with an approach founded in social history of art and reception history.

Articles

For in this subconscious realm, all our urges work without being cowed by those hostile surroundings that affect our outward actions, so that in our conduct we are hampered by the morality of the moment and by our upbringing as a whole, whereby our conscious actions can very easily become conservative . We dare not do anything other than what we happen to be used to.1

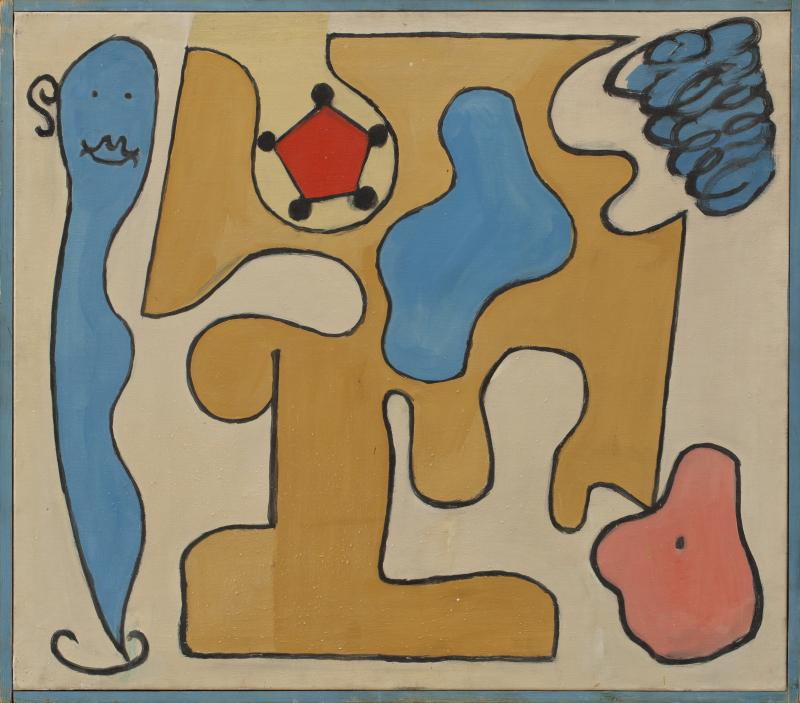

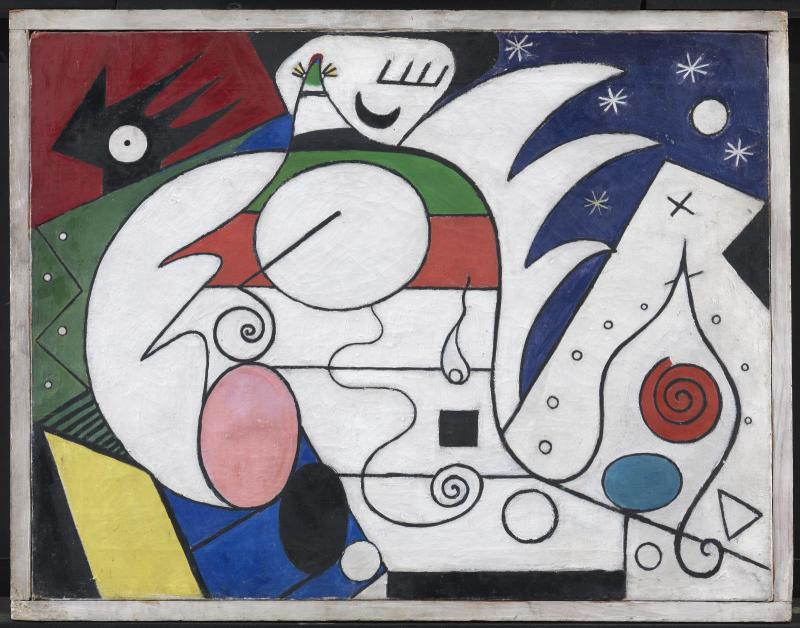

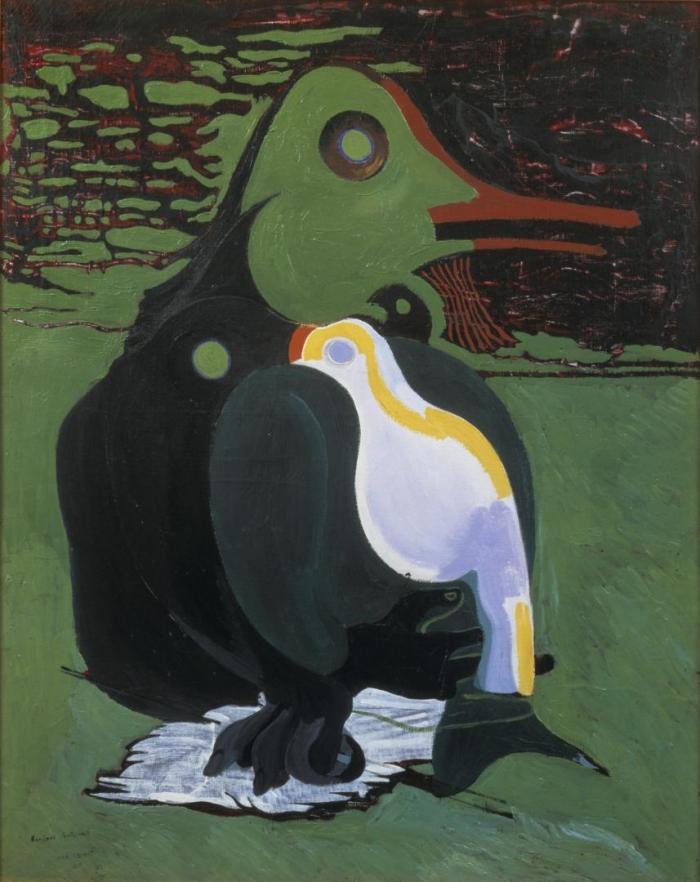

This article will shed light on Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen’s (1909–57) Surrealist endeavours in the 1930s, which, in addition to his well-known oeuvre of paintings, also comprised curatorial work on exhibitions, commissions for public art, collages, drawings, prints and a range of written works including poems, articles and various texts, some with an educational aim, others more akin to manifestos and entries on art theory. The focal point of the article is a study of Bjerke Petersen’s Surrealist art theory illuminated through comparative analyses of the groundbreaking exhibition International kunstudstilling kubisme=surrealisme (International Art Exhibition Cubism = Surrealism), which he arranged in Den frie Udstillingsbygning in Copenhagen in 1935. At kubisme=surrealisme, visitors could become acquainted with works by world-famous artists such as Jean Arp (1886–1966), René Magritte (1898–1967), Salvador Dalí (1904–89), Max Ernst (1891–1976), Alberto Giacometti (1901–66), Man Ray (1890–1976), Joan Miró (1893–1983), Yves Tanguy (1900–55) and Paul Klee (1879–1940). Bjerke Petersen had received tuition from the latter in 1930–31 as a student at the Bauhaus school in Dessau. The exhibition was an event on an international scale in its own time, as is apparent from the small exhibition catalogue that accompanied kubisme=surrealisme: the contributions included one by the ‘father’ of Surrealism himself, André Breton (1896–1966). Bjerke Petersen’s own catalogue text informs us that this was the first international Surrealist exhibition in Scandinavia, demonstrating that in the 1930s, Den frie Udstillingsbygning continued to form the setting of some of the most important events on the era’s art scene.2 With this article, I will apply an approach founded in the social history of art, contributing new and important insights into the relationship between Den frie Udstilling and the avant-garde movements in general, while also considering the specific significance of the kubisme=surrealisme exhibition for the further development of Surrealism in Denmark.

Den Frie Udstillingsbygning – House of the Avant-gardes

In 1891, J.F. Willumsen (1863–1958) and a number of other young artists, including Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916), Johan Rohde (1856–1935), Agnes Slott-Møller (1862–1937) and Harald Slott-Møller (1864–1937) founded Den frie Udstilling (The Independent/Free Exhibition) in opposition to the juried Spring Exhibition at Charlottenborg, which the young artists perceived as a reactionary, academic and conservative institution. The debut of Den frie Udstilling took place on 26 March 1891 at Kleis Kunsthandel, a gallery located in Vesterbrogade in Copenhagen, a week before the annual Spring Exhibition at Charlottenborg was scheduled to take place. At the time, the timing was in itself considered a provocative act of protest on the part of the Den frie Udstilling: being an academic and authoritative cultural body, Charlottenborg was generally expected to take the lead in presenting the topical artists of the time to the general public. In this sense, Den frie Udstilling can usefully be compared to the Salon des Refusés, which, as the reader will no doubt be aware, had been established back in 1863 as a collective protest in opposition to the officially sanctioned art on display at the Paris Salon. Building on this point, Bente Scavenius has succinctly described Den frie Udstilling’s debut as a Succès de Scandale, and as I will go on to show, this designation can be extended to include many of the later exhibitions that took place at the movement’s own venue, Den frie Udstillingsbygning, and that this holds true right up to the time around World War II.3 Even in its first decades, Den frie Udstlling showed exhibition by modernist artists considered outré at the time, including the Symbolist Max Klinger (1857–1920) and post-Impressionist painters such as Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Edvard Munch (1863–1944) and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890).4

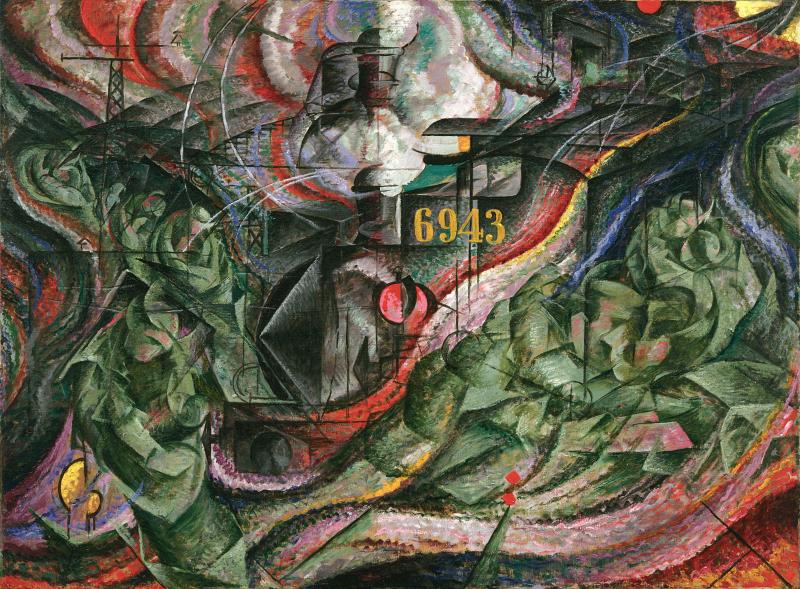

On 11 July 1912 at 2 p.m., Herwarth Walden (1878–1941), founder of the gallery and magazine Der Sturm in Berlin, opened the doors to the first avant-garde exhibition in Denmark. Walden’s exhibition also took place in the Den frie Udstillingsbygning, inviting visitors to view works by prominent Italian Futurists such as Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) [fig. 1], Carlo Carrà (1881–1966), Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), Luigio Russolo (1885–1947) and Gino Severini (1883–1966). However, it should be emphasised that the Futurist exhibition at Den frie was part of a larger international travelling exhibition concept, as the Futurists had had their debut five months previously with an exhibition at the Parisian gallery Bernheim-Jeune. Following this, the exhibition was shown, albeit in different versions, in London, Berlin, Brussels, Hamburg and Copenhagen, and subsequently went on to visit The Hague, Cologne and Munich.5

A headline run in prominent Danish newspaper Politiken on 11 July 1912 testifies to how this was a much discussed and sensational event even before it opened in Copenhagen. It said: ‘Europe’s Great Sensation: Today at 2 o’clock, Futurism takes over Den frie Udstilling’.6 In his memoirs, published posthumously in 1976, the Expressionist artist and member of Die Brücke Emil Nolde (1867–1956) has described how the Futurists spread their extreme opinions through European culture like a storm carrying a breath of fresh air:

‘Like a storm, all the Italian Futurists descended on Berlin and filled the halls with their pictures. They used a type of propaganda never seen before. One evening, they visited my studio, Marinetti and Boccioni, clad in tuxedos, vividly and energetically reaffirming how fantastic and new my prints and pictures were. Their idea – to smash up all the old Italian works of art and burn them in order to bring in gusts of fresh air and create a need for a new art – I have not forgotten, and long afterwards Marinetti’s books and exciting manifestos came flying to us’.7

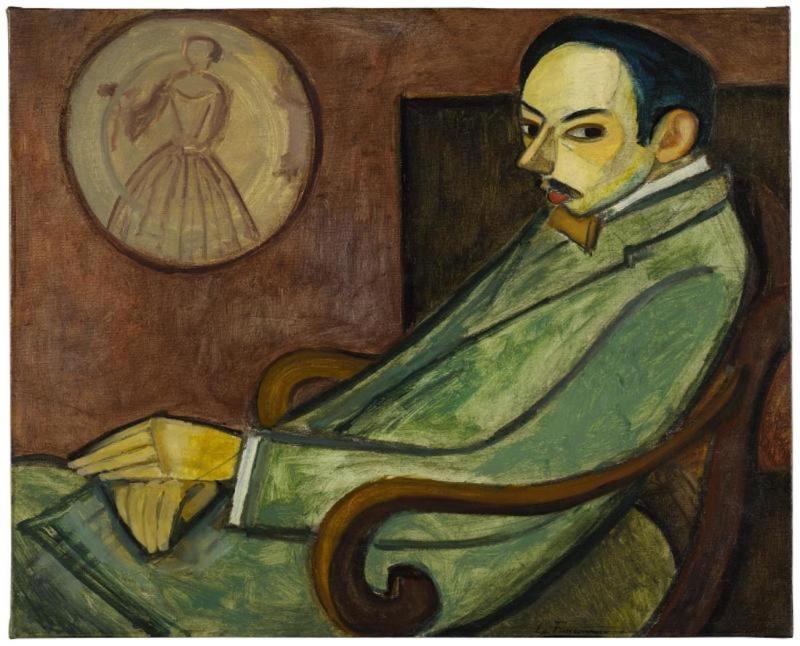

The year after the Futurist exhibition had been launched at Den Frie, Walden returned to Copenhagen, this time to present the exhibition Expressionister og Kubister (Expressionists and Cubists) [fig. 2], a title subtly reminiscent of that of Bjerke Petersen’s kubisme=surrealisme show twenty years later.

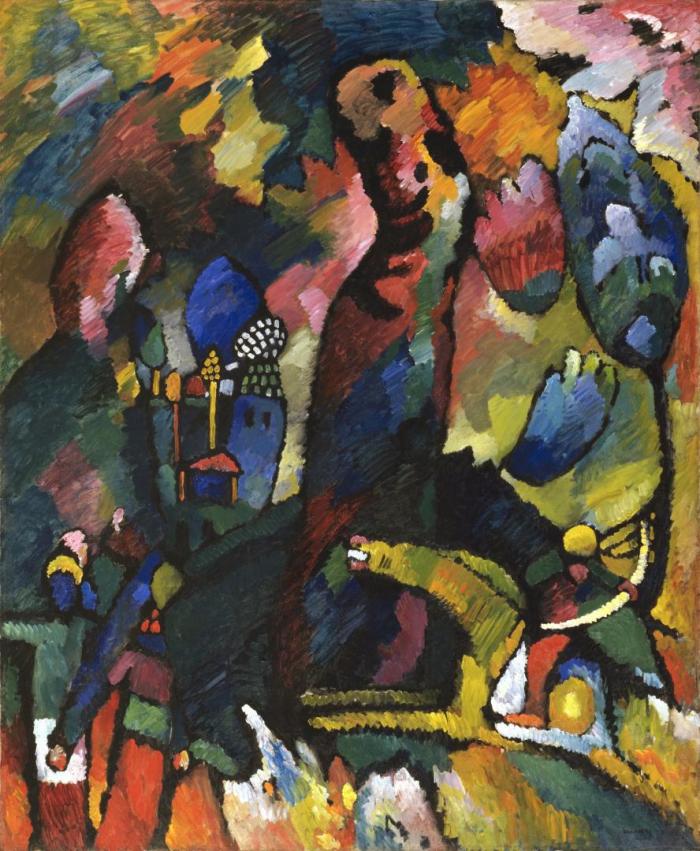

What is interesting in this context is that at this early stage, Walden managed to present Danish audiences to artists such as Klee and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) [fig. 3]; that is, artists whom the Surrealist Bjerke Petersen would not be tutored by until his time at the Bauhaus school in 1930–31.8 While several art historians, including Lennart Gottlieb and Hanne Abildgaard, have pointed out that Walden’s exhibitions did not seem to palpably influence the Danish artists of the time, such as Jais Nielsen (1885–1961), William Scharff (1886–1959) and Vilhelm Lundstrøm (1893–1950), it nevertheless seems reasonable to assume that these exhibitions, aimed at instigating revolution in the arts, had a much stronger influence on the subsequent generations of actual avant-garde artists, not least on Surrealists such as Bjerke Petersen.9 In any case, the Danish Surrealist artist Wilhelm Freddie (1909–95) was among those who praised the Futurist Severini. After a sale of the collection of art collector and patron Christian Tetzen-Lund (1852–1936) – the auction took place at Den Frie in 1925 – many of the works were bought by professor of pathology Oluf Thomsen (1878–1940), a close colleague of Freddie’s father and also known for a treatise written in defence of the young artists who had been perceived as morbid and diseased by the bacteriologist Carl Julius Salomonsen (1847–1924) and his eclectic theory of dysmorphism.10

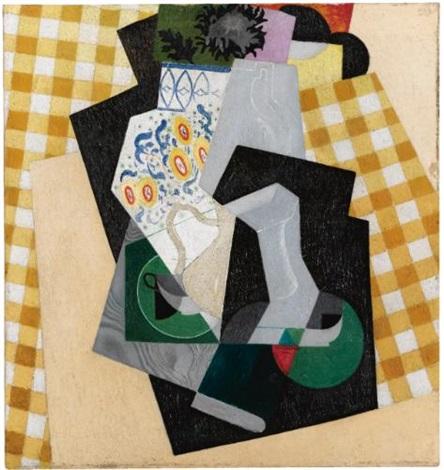

In connection with Thomsen’s investment, the young Freddie had been charged with bringing the paintings bought at the auction to the professor’s villa in Juliane Maries Vej. He brought them there on a handcart, including Severini’s Nature Morte – Hommage á Flaubert from 1916 [fig. 4].

‘Freddie would often tell the story of how Oluf Thomsen asked him if he liked the paintings, to which he replied, “I think that picture by Severini is quite wonderful”. “Would you like to borrow it?” “Yes, please!”. And so Severini’s painting would adorn Freddie’s room “for many, many years”.’11

When Surrealism came to Denmark

In 1924, the same year that Carl Julius Salomonsen died, the author André Breton launched his Surrealist manifesto. Back in 1920 he had already, in collaboration with the activist and poet Phillipe Soupault (1897–1990), developed the idea of automatic writing; a theory that would prove to be one of the most important prerequisites and fundamental principles of the Surrealist movement. In his manifesto (1924), Breton presented a very clear definition of Surrealism, which he described as:

‘Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern’.12

Early Surrealists such as Breton, Louis Aragon (1897–1982), Soupault and Paul Éluard (1895–1952) sought, based on the theories of unconscious urges put forward by psychoanalysis, to create an entirely new language and an utterly free, unfettered way of life, all as part of a much more wide-ranging process of social revolution and upheaval. Later, painters such as André Masson (1896–1987) and Max Ernst developed the frottage technique and other ways of implementing the idea of automatism in a visual arts programme.13 By working in this manner, the Surrealists wanted to create a new reality in which the inner worlds of dreams and the subconscious interacted with the rational external world order, transcending it to enter a kind of super-sensory ‘super-reality’. Bjerke Petersen took this mode of thought to heart when, in his little book about his own drawings, Mindernes Virksomhed (The Activities of Memories) from 1935, he proclaimed that:

‘This young man [Bjerke Petersen] experienced what is about to reveal itself on the sheets that follow. it came to him partly as reality, partly as dreams. in the course of time, dream and reality merged in a series of images accompanied by a few, fragmented words’.14

In other words, the Surrealists’ mission was not solely concerned with creating new images. Rather, it was about redirecting society’s reality, driven by ideas of function and utility, towards a new kind of freedom, unshackled from all and any capitalist, imperialist and bourgeois doctrines and morality. In the second issue of Bjerke Petersen’s magazine Konkretion from 1935, Wilhelm Freddie – expressing views entirely in line with those of Bjerke Petersen, Breton, Soupault and many of the other Surrealists – favoured the reality of subconscious urges over the rational and restrictive external reality perceived by the senses. Bjerke Petersen and Freddie were among the few Surrealists in Denmark who shared the idea that subjective dreams, uncontrolled sexual and animal drives, anarchism and mental impulses were to serve as the basis for building the ideal society and the most universal and truthful art.15 In this sense, the Surrealists took a radical point of departure, one which involved political revolutions. As such, one of the main challenges was – as Bjerke Petersen realised back in 1937 – the question of how to maintain the revolutionary impetus of Surrealism. To Bjerke Petersen’s mind, the main issue was a matter of not letting Surrealism be exploited, amputated, surrender to or become absorbed in capitalist society, with all its commodification and mercantile outlook on the function of art. As Bjerke Petersen wrote in Surrealismens billedverden (The Imagery of Surrealism):

‘Regrettably, if a revolutionary movement grows weak and immoral and sinks back into what it previously saw as something to be opposed, one rarely hears any regrets about what it loses in doing so’.16

While Surrealism later became a counter-revolutionary movement as Surrealist art was gradually reduced to a commodity fetish on the international art market does not alter the fact that it was originally developed, by Bjerke Petersen and others, out of a desire to overthrow and reorganise the values of the established bourgeois society. Like many of the other avant-garde movements that emerged at a rapid pace in the early twentieth century, such as Futurism, Vorticism, Cubism, Expressionism, Constructivism, Suprematism, neo-Plasticism and Dadaism, Surrealism was an international movement built on a strong, shared utopian dream and will to bring about revolution. The agenda of Surrealism and its slogans of ultimate freedom for the masses gave it great artistic and cultural impact in many European countries as well as the United States as far back as the early 1930s – and one of the artists who became extremely important for the spread of Surrealism in the Scandinavian countries was, as has already been mentioned, Bjerke Petersen. In a text called ‘Art and the Revolution’ from 1935, Bjerke Petersen demonstrated a political forcefulness similar to that of the other international Surrealists when, based on a thesis of binary construction, he pointed out that: ‘Today, as always, the world has only one valuable opportunity available to it: revolution, and only one enemy: conservatism – every human being belongs to one of these two movements’.17

At the beginning of 1934, Bjerke Petersen had, in collaboration with Ejler Bille (1910–2004) and Richard Mortensen (1910–93), founded the first Danish Surrealist-oriented avant-garde association, Linien. It should be emphasised, however, that Linien was partly an abstract-Surrealist journal, partly an exhibition forum for the young artists Bille, Mortensen, Bjerke Petersen, Hans Øllgaard (1911–69) and Henry Heerup (1907–93). Accordingly, the first-ever Linien magazine acted partly as a political art journal, partly as an exhibition catalogue for the group’s now-famous – and infamous –debut exhibition opening at Charlottenborg on 17 January 1934. Here, audiences could view no less than 167 abstract-Surrealist works of art. These were greeted with harsh criticism, exemplified by a headline from Berlingske Aftenavis which read, in an untranslatable Danish pun, ‘Children’s pranks and scribbles: linien pokes fun at us at Charlottenborg’.18 Such unfavourable receptions notwithstanding, the event proved a succés de scandale, as Linien achieved attracted no less than 2500 visitors and extensive newspaper coverage during the few weeks the exhibition lasted (the exhibition closed on 31 January 1934).19 Music by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) was played at the venue, and during the exhibition run Heerup would perambulate inner-city Copenhagen while wearing a toilet seat around the neck, bearing the message ‘visit the linien exhibition at Charlottenborg’.20 When Linien was established, a few Danish artists besides the main initiators had already experimented with creating art based on the ideological tenets of Surrealism. Artists such as Osvald Salomonsen (Eugène de Sala) (1899–1987), Heerup, Franciska Clausen (1899–1986), Øllgaard, Bille, Sonja Ferlov Mancoba (1911–84), Mortensen, Freddie and Gustaf Munch-Petersen (1912–38 ), who painted pictures in addition to being a writer, initially all had one thing in common: regardless of their exact intentions, they experimented with creating works while entering into a dialogue with Breton’s theoretical prescriptions.

Strongly influenced by his teachers Klee and Kandinsky, Bjerke Petersen published the book Symboler i abstrakt kunst (Symbols in abstract art) in 1933. Bjerke Petersen’s book is clearly inspired by the Bauhaus books that Klee and Kandinsky had previously published, such as Pädagogisches Skizzenbuch and Punkt und Linie zur Fläche. Beitrag zur Analyze der malerischen Elemente – books of which Bjerke Petersen had gained thorough first-hand knowledge during his time at the school where they were compulsory reading. But at the same time, Symboler i abstrakt kunst is a theoretical and very independent book that engages in a conversation with Surrealism, for example when Bjerke Petersen points out that Cubism had gradually been transformed into both abstract art and Surrealism – a point which would, two years later, find renewed articulation in the title of the exhibition kubisme = surrealisme. In Symboler i abstrakt kunst, the author further asserts that those kinds of symbols that may be called ‘moments of recognition’ should actually be characterised as Surreal.21

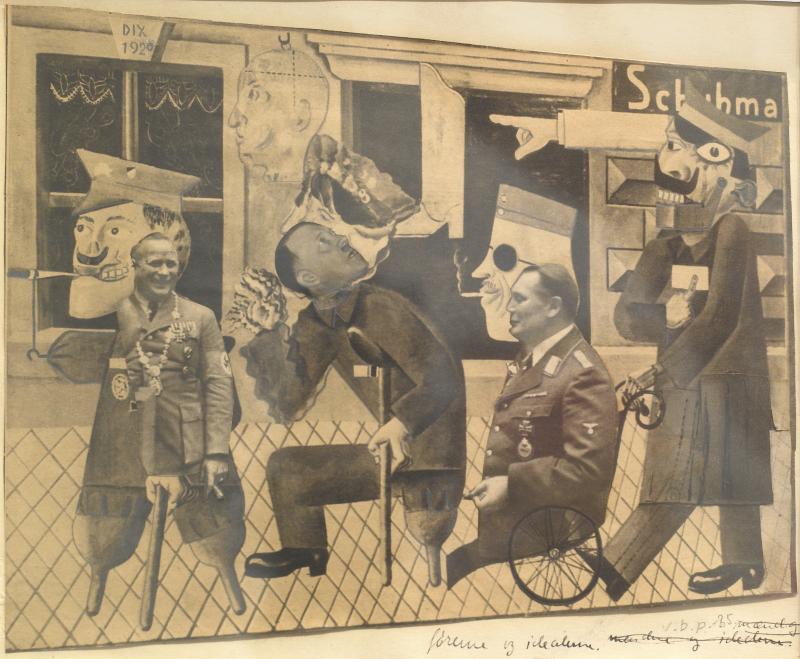

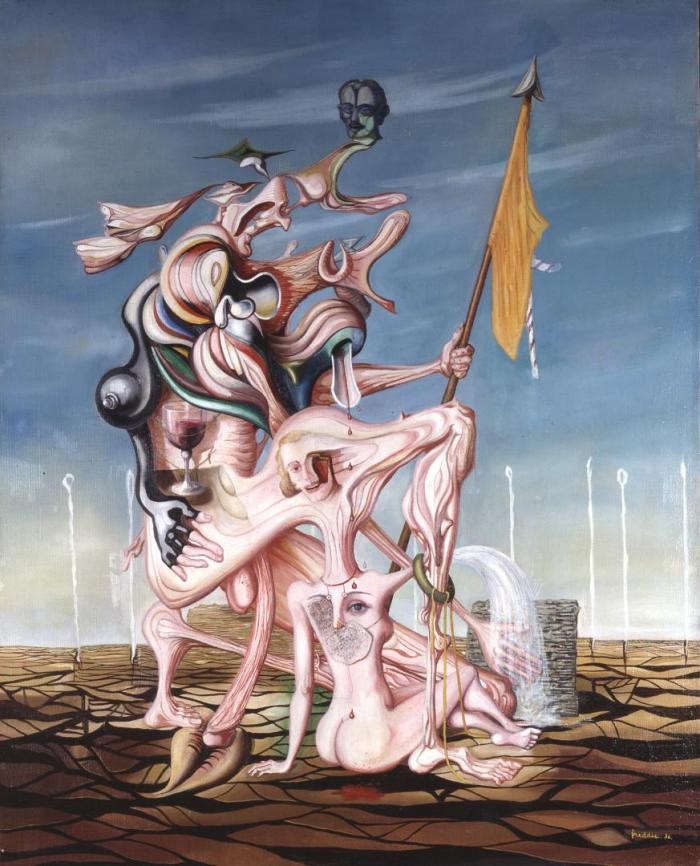

In 1954, Asger Jorn (1914–73) returned to the duality found in Bjerke Petersen’s view of Surrealism and abstraction as two sides of the same coin, a trait which Jorn explicitly described as the book’s real strength. This led to Jorn wanting to publish Symboler i abstrakt kunst in French and as part of the Cobra Library series, although this plan never reached fruition.22 Jorn also sprang from the soil of Surrealism, a trait which manifested itself in his intensive work with automatism and spontaneous-abstract works – endeavours which Jorn continued throughout his artistic career. In 1937–39, Jorn worked with Surrealist drawings and collages intended to serve as illustrations to the writer Jens August Schade’s (1903–78) short novel Kommodetyven (The Thief of the Chest of Drawers). The fact that these small works by Jorn are reminiscent of Bjerke Petersen’s collages from about the same period – including The Ideals Visiting the Exhibition Entartete Kunst from 1935; a work that Bjerke Petersen based on a montage by Otto Dix (1891–1969) shown at the first Dada exhibition in Berlin in 1920 – supports the thesis that Jorn never gave up the idea of initiating a close collaboration with Bjerke Petersen. Jorn’s enduring interest in Surrealism is also reflected in the fact that he bought Freddie’s Verdenskrigens Faldne (The Fallen of the World War) from 1936 for his museum in Silkeborg [fig. 6].23

Several of the works exhibited at Charlottenborg by the Linien artists had titles that referenced Breton’s and Sigmund Freud’s (1856-1939) emphasis on ideas associated with psychology and the spontaneous. For example, Bjerke Petersen exhibited a painting called Befrugtning (Fertilisation) done in 1933 [fig. 7], while Mortensen showed his series Erotikkens Mystik a-j (The Mysteries of the Erotic a–j) from 1933 [fig. 8], and Bille presented Befrugtning på grænsen mellem det gode og det onde (Fertilisation on the Brink between Good and Evil) from 1933 [fig. 9].24

However, Linien would prove short-lived as a homogeneous and collectivist association: in the very same year the group was founded, two incompatible and divergent theoretical positions emerged. This applies not only within the Linien group itself, but to the development of Surrealism in Denmark in general. In other words, what is traditionally described as ‘the rift within Linien’ embedded itself as theoretical, artistic, stylistic and political differences within the genealogy of Surrealism, and so the rift presents Surrealism as a far more complex and multifaceted movement than is often assumed.25

The internal feud in Linien was primarily prompted by the fact that in October 1934, Bjerke Petersen published the book Surrealismen (Surrealism) as the first in a series sharing the common name Liniens bibliothek (The Linien Library). The book was launched while Bille and Mortensen were on holiday together in Sweden, which is to say that it was published on behalf of Linien, but without the two co-editors Bille and Mortensen’s approval of the final manuscript. Bjerke Petersen’s Surrealismen is a controversial and theoretical book. In it, Bjerke Petersen – employing a staccato-like style, completely devoid of any capital letters – argued how the Surrealists should, like so many other revolutionary avant-garde artists, undermine the institutions, abolish the notion of the artist as genius, negate the artwork as object and thus paradoxically distance themselves from art in the sense of an intellectual and autonomous work. In other words, art was to merge with and disappear into everyday and social life, because, as Bjerke Petersen emphasised:

‘surrealism strives for a mode and form of expression that can be used by and appeal to as many people as possible, it uses psychic automatism. surrealism wishes to strip humanity of any notion of artist and talent by increasingly suppressing conscious intellectualism in the creative work. thus, the new world of images, which sets free restrained and restricted impulses and forces, could become the natural form of expression of every human being, presupposing only an absolute capacity for experience based on devotion and belief: art is dead. – life is strengthened’.26

At the time the book was published, neither Mortensen nor Bille held the same revolutionary views as Bjerke Petersen, who was keenly interested in the theories on orgasm proposed by the radical left-wing psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) and Breton’s paradigmatic manifestos urging a revolution. The complete volte-face that Mortensen and Bille apparently made in rejecting the book probably also came as a surprise to Bjerke Petersen, since Mortensen had, earlier that same year, sent a long letter to Bjerke Petersen demonstrating that at the beginning of Linien’s lifetime he too had been in possession of a strong revolutionary impulse. From the letter, which is dated 27 June 1934, it appears that Mortensen adopted a position very reminiscent of the theories of sexual liberation that Bjerke Petersen later presented and argued in favour of in Surrealismen. As Mortensen pointed out:

‘The surface-oriented functional painting has [emphasised] done its duty. We are now in possession of excellent technique and knowledge of modes of expression now we must overwhelm the world with images. there must be piles of art everywhere. not only exclusive (the other way, we end up as jesuses in jerusalem) we want to sally forth and make embroidery patterns in festive anal-sadistic ornaments for delicious peasant girl bodies and lie in their arms.

I live here in home-mission circles where all life and all celebrations and all ornamentation have been stopped. [Words crossed out] here they are so far down in the womb, they live practically before their birth so that they know neither ural anal oral nor any other form of life.

our lives must be all celebrations. the phenomenon of the celebration itself [emphasised] interests me a great deal and we must get those competent to do so to make a campaign for new symbolic holidays and ceremonies that reflect the depths of life and in which we can all participate’.27

Strong influenced by Reich and Breton, Bjerke Petersen’s book also warmly advocated the cultivation of free sexual drives of any kind, a rejection of all rationality governed by reason, and the upgrading of various anarchist manifestations with especial focus on the child’s unrestricted rights. It is no coincidence that Bjerke Petersen created numerous public works of art and decorations aimed primarily at children and teachers: according to the Bauhaus school’s precepts, art should – somewhat paradoxically – possess utilitarian and didactic social value. Corresponding views can also be found in Mortensen’s thinking, as is apparent from the above-mentioned letter:

‘of course, P.H. will be sorely disappointed when we enter the scene with psychic-materialist functionalism. we want to add decoration to the façades of all houses. (they have always had that.) but now they must be more splendid than ever, and rest assured that here we strike at something so fundamental to the human mind that in a few years’ time we have a wave of people with us. – it will be a huge mess in the beginning everyone will think that now the bourgeois sensibilities are winning’.28

In 1930, Bjerke Petersen created murals for the Birkerød State School [fig. 10], where he himself had been a pupil alongside Mortensen and Bille, and also created art for Højdevangen’s School on Amager [fig. 11]. Bjerke Petersen sent an application regarding his work at Højdevangen’s School to the New Carlsberg Foundation in 1930, meaning that the foundation deliberately chose to support a clearly ‘revolutionary’ project. He worked on these murals for a long period of time, extending from 1932 to 1939, thereby preceding, by five years, other similar projects such as Mortensen’s now-lost art for the kindergarten Husum Børnehus and the art created for Sophus Bagger’s (1848–1943) kindergarten in Hjortøgade in the Østerbro district of Copenhagen, done by Asger Jorn and several other artists from the Høst group, including Carl-Henning Pedersen (1913–2007), Ejler Bille, Richard Winther (1926–2007), Else Alfelt (1910–74) and Egill Jacobsen.

In Surrealismen, Bjerke Petersen also spoke warmly in favour of the elimination of any cult of personality, just as he, as expressed in the quote above, did not see Surrealism as an actual art movement, but rather as a socio-political and revolutionary successor to art. The ultimate goal of art thus became its own dissolution, a point on which Bjerke Petersen was entirely in line with Breton, foreshadowing the goals later expressed by the International Situationists and, thus, by the author, film director and theorist Guy Debord (1931–94) and Jorn regarding the elimination of art in the acting community; ideas which were persistently repeated from 1957 until the Situationist group’s final dissolution in 1972.

In Reich, whom Bjerke Petersen read diligently, one also encounters theories about how the subjugated proletariat can set itself free from the domination of capital power through a natural emancipation of what Reich perceives as a true and healthy sexual drive in the individual.

‘The relative psychic tameness of the mass – it must also seem incomprehensible to the insightful capitalist – must among other things also be added to the account of the relatively unbound genius, because its satisfaction deprives the sadistic tendencies of their energy […] But when brutality awakens in an individual from the mass it is far more primitive and negligent than the brutality of the landowning class, because the façade of the veiling cultivation is lacking’.29

It was this drive towards revolution and willingness to use violence that Mortensen and Bille could not agree with. The manifesto-like form of agitation used in Surrealismen thus resulted in Bjerke Petersen’s immediate expulsion from the circle which would, from this point on, define the profile of Linien and its new Surrealist programme. For example, Bjerke Petersen had put forward the following description of Surrealism in an unpublished manuscript from 1934 in which he, in contrast to Bille and Mortensen, described it as a form of anti-art:

‘Surrealism is not an art form or art movement, but an outlook on life of a highly revolutionary nature, as we absolutely distance ourselves from sexual restraints of any kind, from all snobbery and admiration pertaining to individual persons, whether Hitler or Lenin, from any class division, from all coercion in general and finally, in a narrower sense within the visual arts, from all imitation and portrayal of persons, instead proclaiming our goal to be man’s freest expression, recognising only the direct personal experience of every thing’.30

After the rift in 1934, two specific directions were outlined for Surrealism, as is made explicit in no. 7 of the Linien magazine, published on 20 November 1934. An article headlined ‘linien distances itself from Bjerke Petersen’s book: Surrealisme’ clearly shows how Mortensen and Bille felt a need to assert themselves as representing one of two incompatible camps. They particularly distanced themselves from the irrational elements, the aspects driven by primal urges, as is evident from the following excerpt from a text signed ‘The editors of Linien’, meaning Bille and Mortensen: ‘one of the main objections against the book [Surrealismen] concerns its constant focus on the unimpeded dominion of the deeper urges, the unwavering ridiculing of reason in life’.31 They go on to say that ‘towards the end of the book, bj.petersen appears to believe that the proletariat’s revolution should be replaced by a so-called psycho-materialistic one. We can in no way agree with him on this point’.

However, the aforementioned letter sent by Mortensen to Bjerke Petersen earlier that year clearly shows that Mortensen had actually shared several of the views presented in Bjerke Petersen’s book. Furthermore, before the rift, Mortensen had also regarded Dalí as one of the most important Surrealist artists, a situation which would change after the disruption, a point to which I will return later:

“det er sikkert en god ide med et samarbejde situationen er jo nu saadan at vi mere end nogen sinde behøver saglig støtte fra andre sider. den psykoanalytiske underbygning for kunstnerisk skaben er nu noget fundamentalt for intellektuelt skabende. – ligeledes har vi brug for økonomerne. jeg anser dali og ernst for de 2 eneste der for alvor ved hvad de beskæftiger sig med. jeg forstaar godt de andre surrealister tænker sig lidt om. (masson er for øvrigt ikke surrealist han blev højtideligt udstødt af ligaen for et par aar siden).

læs den artikel i minotaure III af dali om “den skrækkelige spiselige skønhed i den moderne arkitekturs stil”. hans brev om erotisk frihed gaar meget videre end vi først havde tænkt. dette at han bortskærer den idealisme kunsten har været ført af de sidste 30 aar og som har [ulæseligt ord] [ulæseligt ord] af det teoretiske arbejde betinger en pludselig rigdom i fantasiens udtryk.”32

From a letter dated 4 November 1934 and sent by Bjerke Petersen to Egon Östlund (1889–1952), who was one of the main initiators of the Halmstad group, it appears that Bjerke Petersen, following Mortensen’s and Bille’s rejection of his book, saw Linien as having been completely dissolved. For as he announced in the letter:

‘i am very sorry to have let you down last thursday, but here is the thing: when i got on the train in Oslo, i bought politiken and found in it a uniquely fierce, personal attack – indeed assault – on me, perpetrated by my two fellow workers – this made me give up the meeting with the halmstad painters, as i realised a complete revolution must take place in our circle’..33

The same letter also states that the exhibition concept regarding ‘Cubism = Surrealism’ had to be reassessed and replanned in a new and different way compared to the original exhibition design used by Linien. In other words, Bjerke Petersen’s kubisme=surrealisme was to replace Linien’s exhibition while establishing a marked and visible distance between the two. This meant that Bjerke Petersen would initially simply and subtly take over working on the exhibition already planned by Linien at Den frie Udstillingsbygning when the group suffered its rift, although it would of course be completely different from the kind of exhibition that Mortensen and Bille would find desirable, being far more geared towards revolution. In a new and marked departure from the first Linien exhibition, Bjerke Petersen placed greater emphasis on the integration of Swedish Surrealism which had consolidated in the Halmstad group, thereby trying to establish a Scandinavian Surrealist alliance and faction akin to the international Surrealism based in Paris: ‘during the autumn of 1935 I hope to be able to arrange a new exhibition [two words underlined] with a partly different format, at which I would very much like [two words underlined] to have the Halmstad painters included’.34

Concretion and Surrealism after the rift in Linien

In 1937, Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen’s father, Carl V. Petersen (1868–1938), who was an art historian and director of the Hirschsprung Collection, wrote an introductory text to the 11th volume in the series Danske Kunstnere (Danish Artists), a themed effort about the leading surrealists in Denmark. The book launched the art of Rita Kern-Larsen (1904–98), Elsa Thoresen (1906–94), Harry Carlson (1891–1968), Freddie and Bjerke Petersen; all artists who represented what now constituted the revolutionary wing of Danish Surrealism. Interestingly, Carl. V. Petersen’s contribution to the book makes no mention whatsoever of the artists who continued in Linien after the parting of the ways in 1934 (Mortensen, Øllgaard, Heerup and Bille), and all the while he greatly highlights those revolutionary and radical aspects of Surrealism from which Bille in particular explicitly distanced himself.35

Art historian Troels Andersen has even attributed the generally negative outlook that has, until recently, characterised the reception of Bjerke Petersen’s art to the sundering of Linien. However, Andersen also asserts that one of the reasons for the rift can be found in the way in which Bjerke Petersen’s works were very carefully thought out on a theoretical basis prior to their execution, whereas Mortensen’s and Bille’s arose out of more spontaneous explorations; in fact, the latter had a closer kinship with the later spontaneous-abstract artists associated with the journal Helhesten and the working methods of the artists’ group CoBrA, a fact that has often been downplayed or completely overlooked in scholarly studies.36 At any rate, it seems reasonable to view the falling-out with Linien as the real starting point of Bjerke Petersen’s more politically radical understanding of Surrealism, prompting a stronger connection to Breton and international Surrealism. Bjerke Petersen’s views thus became synonymous with the statements already found in many existing Surrealist programmes. As a Surrealist leaflet from January 1925 put it: ‘We are specialists in Rebellion. There is no means of action that we are not, if necessary, ready to employ […] We say more specifically to the Western world: SURREALISM exists’.37 Or as Breton put it in his preface to kubisme=surrealisme, the objective was still to build a joint, international, revolutionary front against any conformism and exploitation of unlimited freedom:

‘Fate has long since stopped playing games with the idea of Surrealism, and those who were the first to carry the idea aloft continue to see, with great emotion, how the movement follows its difficult, but assured path, no longer just in Paris, but also in Copenhagen as in Barcelona, in London, Brussels, Prague, Belgrade, New York, Buenos Ayres, Tokio, it radiates with all its splendour, with the light of salt, through the works of our friends Erik Olson, Vilh. Bjerke-Petrsen, Eiler Bille, Richard S. Mortensen, who have in the spirit of fraternity encouraged the Surrealist artists in France [to] join them, and the idea thus makes us all the more impatient to be confronted with later works that are always more universal, and which are marked by the desire that inflames the rejuvenated eye of the world’.38

Remarkably, Breton mentions both Mortensen and Bille, indicating that he was unaware of the quarrel that had occurred within Linien. The fact that as late as 1 November 1934, Bjerke Petersen urged Mortensen and Bille to take over the planned Linien exhibition – the show that would eventually become International kunstudstilling kubisme=surrealisme, testifies that initially, Bjerke Petersen did not want to take on the major effort of setting up the exhibition alone.39

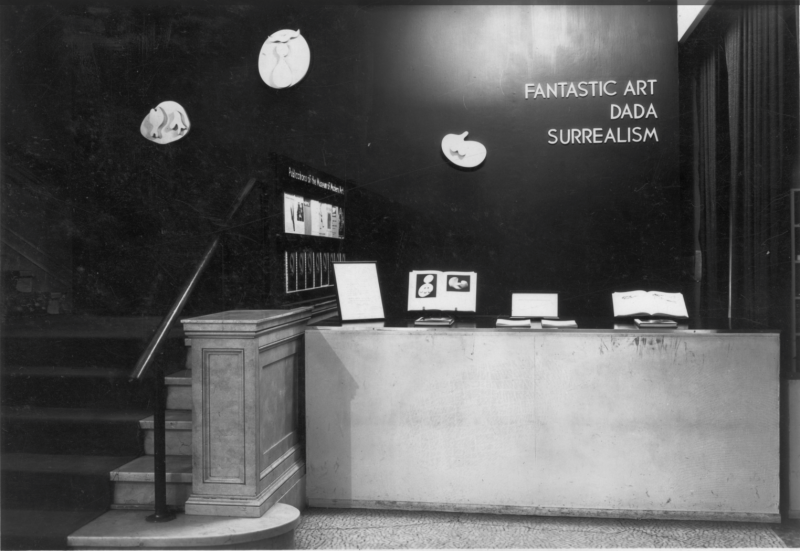

In addition to working on International kunstudstilling kubisme=surrealisme, the year also saw Bjerke Petersen publish the book Mindernes Virksomhed (The Activities of Memories, 1935), a volume consisting of drawings made by himself, as well as the first issue of the journal Konkretion, of which he was also editor. Furthermore, he published two small, albeit significant books about the art of Wilhelm Freddie and the Swedish Surrealist and set designer Erik Olson (1901–86). Thus, the year 1935 should be seen as a watershed moment in the history of Surrealism in Denmark, not least because Bjerke Petersen set out a far more radical direction for Surrealism, understood here as a more avant-garde and politically formative movement than the one represented by Mortensen and Bille. It is also no coincidence that in addition to his work on arranging the exhibition at Den frie Udstillingsbygning in 1935 and the publication of Konkretion, Bjerke Petersen also contributed illustrations and textual material to some of the most important international Surrealist journals, specifically Cahiers d’art and Jeune Europe. In 1936, Bjerke Petersen also took part in the International Surrealist Exhibition in London and in the now famous Fantastic Art – Dada Surrealism [fig. 12] which Alfred Barr (1902–81), the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curated and exhibited at the museum in 1936–37.

In addition to Bjerke Petersen, many of the international Surrealists whom Bjerke Petersen had already presented in his exhibition at Den frie Udstillingsbygning were also featured in the New York exhibition, including Dalí, Magritte, Giacometti, Jean and Sophie Taeuber Arp (1889–1943), Man Ray, Max Ernst, Miró, Tanguy, Klee and Maret Oppenheim (1913–85). In addition to these representatives of Surrealism, all of whom are now internationally recognised, Barr’s exhibition also showed works by Harry Carlsson (1891–1968), Freddie, Rita Kern-Larsen and the Danish-American artist Knud Merrild (1854–1956) as well as several now lesser-known Scandinavian Surrealists, including members of the Halmstad group such as Sven Jonson (1902–81), Stellan Mörner (1896–1979) and Wald. Lorentzen (1899–1984).40 However, Barr’s exhibition included no works by Bille, Mortensen, Øllgaard or Heerup. Viewed in this light, Bjerke Petersen’s artistic and theoretical endeavours can be seen as an integral part of international Surrealism and its goals. The works presented at this level can be said to be a Scandinavian faction of the politically radical international Surrealism movement understood as an avant-garde formation, with Bjerke Petersen, Carlsson and Freddie as its main representatives. The fact that Bjerke Petersen helped to focus on Scandinavian Surrealism as part of a much larger, widely proliferating international avant-garde movement is corroborated by how he, as editor-in-chief of the magazine Konkretion, chose to publish a special themed issue 5–6 in 1936 in which he presented several contributions by Breton, Éluard, Tanguy and Dalí created especially for the journal – meaning that he was able to present new, original texts by some of the most important Surrealists that he had already showcased at his groundbreaking exhibition at Den frie Udstillingsbygning the year before.41

In 1937, Mortensen, Bille and Øllgaard arranged the exhibition Liniens sammenslutning (The Linien Association), also at Den frie Udstillingsbygning. The Linien exhibition came into being because Mortensen, Bille and Øllgaard had approached some of the Surrealist artists in Paris, wanting to show their art at their Copenhagen exhibition. Accordingly, Øllgaard and Bille visited Jean Arp and his wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp, while Richard Mortensen paid Max Ernst a visit in his fourth-floor flat in Rue des Palmes. They went on to buy Bonjour Satanas, 1928 [fig. 13] from Ernst for DKK 300. Furthermore, they paid several visits to Alberto Giacometti, to whom they were introduced by Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, who lived in Paris at the time and knew Giacometti personally.42

Linien’s exhibition at Den Frie in 1937 presents several interesting aspects. In contrast to Bjerke Petersen, Linien combined artists from several different groupings. While they showed works by Surrealists who also appeared in the kubisme=surrealisme exhibition, such as Ernst, Tanguy, Miró, Klee and Jean Arp, they also, unlike Bjerke Petersen, featured works by the early Concrete/abstract artists from the Dutch De Stijl group such as Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) as well as Kandinsky from the Bauhaus school. Also in contrast to the previous show, Linien’s 1937 exhibition did not feature works by those Surrealists whom Bille later defined as ‘entrail artists’ or ‘cadaver Surrealists’, meaning the revolutionary wing rallying around the surrealist magazine Minotaure. Founded by Albert Skira (1904–73) in Paris, Minotaure was published from 1933 to 1939. As has already been mentioned, it contained contributions from the international avant-garde artists from whom Bille distanced himself, such as Magritte, Man Ray and not least Dalí.43 On the back cover of the catalogue of the kubisme=surrealisme exhibition, Bjerke Petersen had placed an advertisement for Minotaure, proclaiming it to be ‘The Leading Art Magazine of our Present Time’. The fact that the Danish Surrealists who were in dialogue with the so-called ‘cadaver Surrealism’ – a direction often referred to as psychographic or photographic Surrealism – were not shown at Linien’s 1937 exhibition is remarkable. This meant that the audience had no opportunity to see works by either Bjerke Petersen, Freddie, Thoresen, Kern Larsen, Eugène de Sala or Erik Ortvad (1917–2008). Considering this issue in the light of reception history, it is interesting to note that it was also these ‘unhealthy’ avant-garde, anarchist and politically radical Danish Surrealists who were not attributed any importance until late in art history, meaning in the 1960s and onwards. A marked contrast to the abstract-symbolic Surrealists with their focus on pure lines, symbols and forms, represented by artists such as Mortensen, Bille, Egill Jacobsen and Heerup, who all achieved far greater commercial success.44

Dalí was richly represented in several issues of Linien’s magazine until the rift in 1934, meaning as long as Bjerke Petersen was part of the editorial staff. In no. 5, Dalí even had one of his highly controversial texts published. Called ‘The New Colours of Spectral Sex Appeal’, it stated that:

‘[…] woman will become spectral through the inarticulation and deformation of her anatomy. ‘the demontral body’ is what is to be achieved and the icy truth of feminine exhibitionism, which will become a highly critical point, allowing for the enjoyment of each piece individually, isolated to be eaten piece by piece, an anatomy clothed in claws’.45

Also interesting is the fact that Bjerke Petersen’s as well as Bille and Mortensen’s exhibitions on Surrealism, which marked out two different overall directions in the development of Surrealism, were shown at Den frie Udstilling just a few years apart, and that both exhibitions saw the participation of local Scandinavian artists who are now either entirely forgotten or have been marginalised in the historical reception of the avant-garde – a fact I have previously pointed out as problematic.46 For example, Bjerke Petersen’s exhibition included several names that are rarely addressed in present-day art history.47 As has been pointed out by art historian Lise Lotte Blom, it is also remarkable that Bille and Mortensen took over the running of the journal and the name Linien after the break-up, while Bjerke Petersen, being a member of Den Frie, was allowed to work entirely autonomously on the exhibition concept that formed the basis of the kubisme=surrealisme exhibition.48

Bjerke Petersen’s kubisme=surrealisme not only featured acclaimed Surrealists such as Man Ray, Magritte, Miró, Tanguy, Klee, Dalí, GAN (Gösta Adrian-Nilsson) (1884–1965), Méret Oppenheim, Max Ernst, Oscar Domingues (1906–57) and Valentine Hugo (1887–1968), but also quite a few minor or even entirely unknown Scandinavian Surrealists such as Halmstad group members Jonson, Lorentzen, Mörner and Axel Olson (1899–1986), Christian Berg and others. Other contributors included the German artist Erni Graumann, Norwegian Surrealist artists (1907–98) and Bjarne Rise (1904–84) and, from Denmark, Rie Nissen (1904–88), Mille Heerup (1911–99), the architect and sculptor Egon Møller Nielsen (1915–53) and Gustaf Munch-Petersen. At Linien’s Surrealism exhibition Liniens sammenslutning in 1937, Bille, Mortensen and Øllgaard presented no works by Freddie, Dalí, Magritte, Oppenheim or Bjerke Petersen. Also in contrast to Bjerke Petersen, they did, however, show works by some of the artists who would subsequently rally around the journal Helhesten and, later yet, the spontaneous-abstract international CoBrA movement, including Asger Oluf Jørgensen (Jorn), Egill Jacobsen, Carl-Henning Pedersen (although he was not featured in the printed catalogue, but only on the vernissage card). Furthermore, Bille and Mortensen had also included works by the naturalistic Funen Painters. The integration of an older landscape tradition engaging in a dialogue with the avant-garde thus permeated Linien’s exhibition, another contrast to Bjerke Petersen’s consistently emancipatory, subversive and politically radical projects. It should be added, however, that Bille probably also had difficulty in appreciating the ‘romantic landscape art’ to the same degree as the efforts which would later characterise the spontaneous-abstract artists’ contribution to Helhesten.49 For as the journalist and art critic Gunnar Jespersen (1922–94) has shown, Bille had, on a guided tour of the Linien exhibition, been bitingly ironic when reporting how the ‘amateur painter’ Knudaage Larsen (1900–79) had outshone the exhibited works by Miró, Klee, Arp , Max Ernst and Tanguy.50

In Alfred Barr’s book Cubism and Abstract Art, first published in 1936, the same year that Bjerke Petersen took part in Barr’s famous Fantastic Art – Dada Surrealism, Barr came up with a theory asserting that one should distinguish between two types of Surrealist painting.51 Barr defined one of these directions as the automatic; the other as dream pictures. Whereas the former is based on absolute spontaneity and unfettered painterly impulses rooted in Cubism and the ideas of Klee and Kandinsky, a group in which he included Surrealists such as Miró, Masson and Arp, the latter direction produced dream images in a ‘realistic’ style with deep roots in Flemish and Italian traditions dating back to sixteenth-century art. This camp included the psychophotographic Surrealists such as Giorgio Chirico (1888–1978) Dalí, Magritte and often Ernst.52 Interestingly, Barr’s theoretical considerations echo the separate directions that the two Danish Surrealist exhibitions at Den Frie can be said to represent. However, it should be emphasised that Barr had no special interest in Scandinavian Surrealism. From a letter to Bjerke Petersen dated 30 September 1936, it is apparent that Barr had only very scant knowledge of the Surrealist art introduced to him by Bjerke Petersen. This is also clear from the fact that in a previous letter, Barr had asked Bjerke Petersen whether Bille painted pictures. To this we may add that Barr has known little about Bjerke Petersen himself, as the letter comes across as a long CV and also contains a wealth of information about Bjerke Petersen’s contact with the other international Surrealists, not least Breton.53

Conclusion

After parting ways with Linien in 1934, Bjerke Petersen embraced the realistic or psychographic tradition – what Bille defined as ‘cadaver Surrealism’. By contrast, Linien’s 1937 exhibition focused on painterly or symbolic Surrealism. Bjerke Petersen is likely to have been influenced by Barr’s theory, as Bjerke Petersen not only took part in the Fantastic Art – Dada Surrealism exhibition, but also wrote several letters to Barr, both before and after his stay in the United States in 1946, testifying to his enduring interest in Barr’s exhibition projects and the unfolding life of Surrealism. Bjerke Petersen’s interest in Surrealism continued even after he himself ‘converted’ to working with nonfigurative Concrete art, a field that would occupy him both theoretically and artistically in the last ten years of his life.