Summary

First published in Danish in: Periskop. Forum for kunsthistorisk debat, 4, 1995, pp. 43-63

Article

During the early twentieth century Kristian Zahrtmann (1843-1917) executed a series of history paintings featuring the nude male body or grand women from history.1 Several of these works were met with the disapproval of the contemporary art critics.2 At that point Zahrtmann was among the most established figures in the Danish art world, cofounder of Den Frie Udstilling, teacher at and cofounder of Kunstnernes Studieskole, and the focal point of the artists’ colony founded by him in Civita d’Antino east of Rome. His scandalous pictures brought into play notions of sexual inversion in representations of eroticized male communities and a theatrical rendition of femininity.

In order to understand the homosexual presence in art and art criticism at the turn-of-the-century I shall first consider its emergence in Denmark during the later nineteenth century as a modern category, tied to an identity with its own psychology and even pathology. The term persona deeming his artistic identity marks a cultural phenomenon, which he and others actively produced in different verbal and visual discourses. It is in relation to these that I shall consider different notions of sexual inversion. Art criticism will be playing a significant part when considering the responses the images triggered at the time of their creation. The analyses of his late paintings shall be introduced by some general considerations regarding his project as an artist, since his later work works, even though outré, operate with notions of style and content that were present in his earlier production.

II

Several factor contributed to the emergence of the invert in Northern Europe during the second part of the nineteenth century. With the growing industrialization came an increasing visible male prostitution emerging from the working classes. This contributed to creating a broader awareness of the existence of sexuality between men. In Copenhagen the first same-sex subculture with the possibility of anonymous sexual contacts emerged in the 1860s. For the bourgeois society, which set respectability among its chief virtues, the male invert became a scapegoat because of his presumed unbridled promiscuity, he being perceived as a threat to the family and a subversion of the military.

Through a study of criminal cases against inverts in nineteenth-century Denmark the historian Wilhelm von Rosen demonstrates how homosexuality went from being a relatively unknown phenomenon to a public concern that was persecuted systematically.3 This culminated in The Great Morality Scandal (Den store Sædelighedssag) in 1906-07 with interrogations and juridical persecutions of homosexuals. The case was followed by a number of public meetings against these people throughout the country.4 This was the background against which the homosexual emerged as a type. From being a relatively unknown and peripheral figure who performed sinful acts against nature the male homosexual was constructed as a character with a particular psychology and even anatomy, a third sex that shared the characteristics of the opposite gender, hence the term “invert”.

Unlike the intolerance of public opinion, the medical doctors of the period often took a different point of view, and at times almost symbiotic relationships developed between doctors and homosexuals. The latter encountered in the former an authority that could explain and justify their existence while the former were strengthened in their professional competence. The doctors defined the invert as a person with innate qualities that normally belonged to the opposite sex. Those qualities were tied to inherited neurasthenia and a weakening of the nervous system reinforced by masturbation at an early age. Typically the doctors rejected the theory regarding the choice of same sex-partner as the result of excessive refinement and a depraved longing for new kinds of pleasures.5 Homosexuals carried a stigma, and society, according to the doctors, ought not to burden them more than absolutely necessary. The medical professionals became spokesmen for the legalization of sexual intercourse between men, an advanced and sophisticated point of view for the time. In this vein Chief Psychiatrist Knud Pontoppidan lectured on perverse sexuality in defense of a 39-year old grocer, who had gotten into trouble with the law after having touched a young man in an unseemly way in the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen.6 In his elucidation of perverse sexuality Pontoppidan concluded that the accused could not be seen as responsible for his actions, because they were the result of his inherited degeneration. That the grocer had an insane aunt only supported Pontoppidan’s theory. He also concluded that while the body of the pervert male developed normally then his mind revealed traces of softness and effeminacy, whereas the pervert woman would have a decisive character and a tendency toward emancipation.7 In this narrative the personality of the invert emerged as a perversion of bourgeois gender roles. Social standing became part of the stereotype regarding the male invert. He was seen to belong to the middle and upper classes, hence the notion of his cultured and/or decadent being. He also became a politically important character in the attempts of the politicized working classes in attacking the political right. A series of defaming articles, published in the workers’ newspaper Socialdemokraten in 1885, attacked the rightwing party Højre and its newspaper Avisen by “revealing” a number of sex offenders in these circles. To Socialdemokraten this was a token of the moral decline of the upper classes.8 Male prostitutes came from the working class and typically did not identify with the homosexual role, which could have been a dangerous social transgression.9 The gradual emergence of the invert in Denmark during the last decades of the nineteenth century meant that he became part of a broader public consciousness. During the romantic area of the early nineteenth century, friendship between men could find expression in hugging, kissing, holding hands, and the exchange of highly emotional letters. The later period took a suspicious stand to such friendships and expressions of men’s mutual affection as potential symptoms of perverse sexuality, to be observed and controlled.10

An example of the change in public attitude is exemplified by the Student Organization (Studenterforeningen) of the University of Copenhagen. At the annual carnival of the organization men would dress up in women’s clothes, a tradition rooted in the first part of the nineteenth century. During the carnival of 1876, however, the prerequisite was made that students, who intended to cross-dress, had to report this in advance.11 sThat same winter rumors began to flourish of sex between the members of the Student Organization. The demand that cross-dressing be reported in advance of the party could be seen as an attempt at policing potential dangers of same-sex sexuality. This was the first time in Danish history that effeminacy and illicit sexuality between men were connected.12

Med til den mandlige kontrærseksuelles konstitution som udslag af hans kvindelige disponering hørte desuden kunstneriske evner, et højt kultiveret væsen, sarte nerver og en sans for sirlige boligindretninger.

III

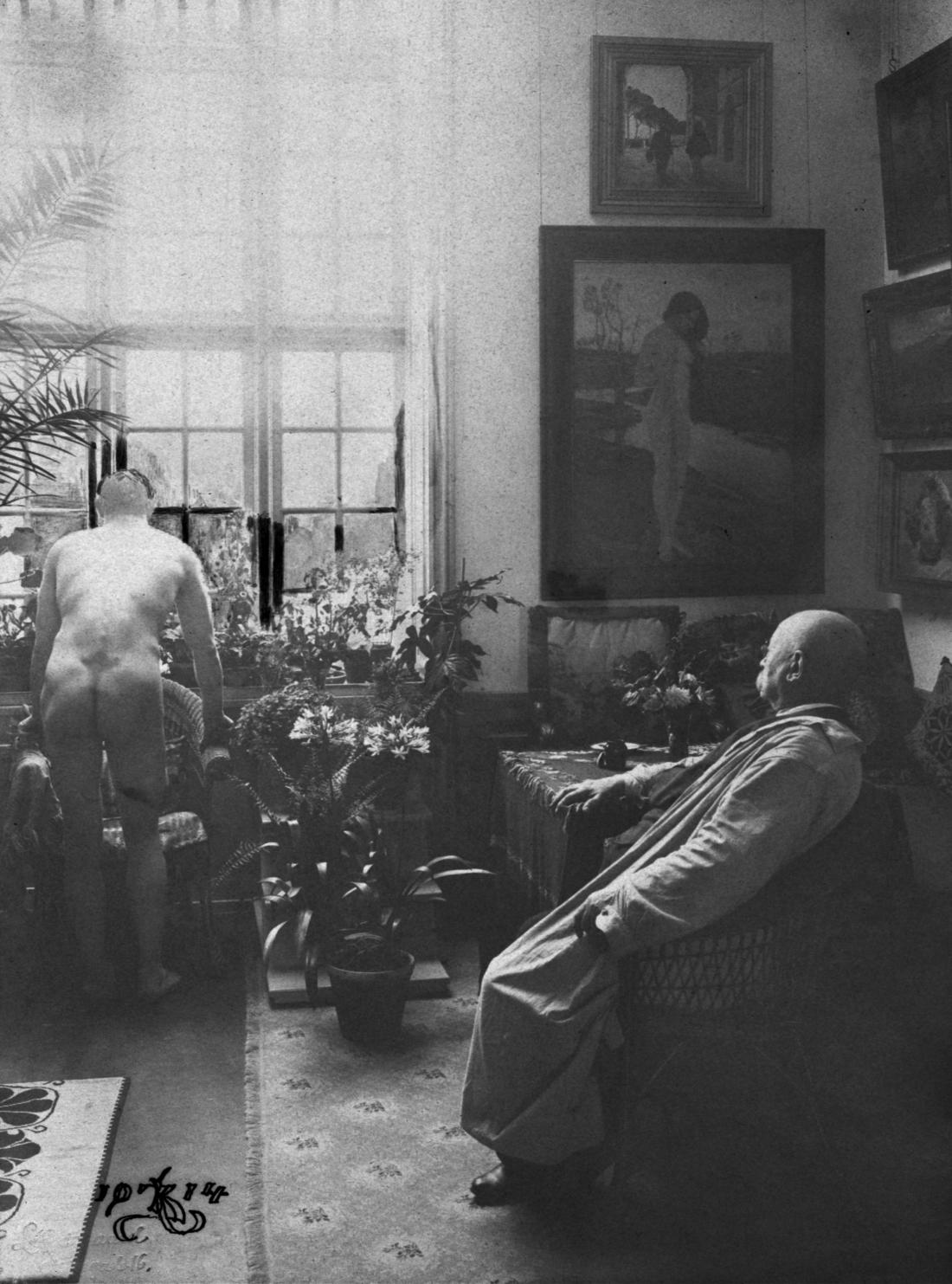

In his later years Kristian Zahrtmann became somewhat of a media figure. In newspaper appearances he can be seen to embody several of the cultural patterns that had come to be identified with the invert gentleman, to whose feminine disposition belonged artistic skills, a highly cultured being, delicate nerves, and a flair for dapper interiors.13 The newspaper interviews both testify to Zahrtmann’s internalization of the homosexual role and the desire of journalists to represent him in this light. The interviews took place in his fabulous studio where he received guests in the Casa d’Antino, built for him on Fuglebakken, Frederiksberg, where he settled in 1912. The journalists typically described the interior with its paintings, smaller sculptures, many plants, eighteenth-century wool embroideries from Bornholm, oriental carpets, and two screens. Of these one was in rococo style inserted with photographs and the other showed Sienese pageboys, embroidered by Zahrtmann’s mother according to his designs.14 The journalist characterized him as the chatty, gracious, elderly bachelor, offering his guests oranges. The artists often let himself be photographed in the studio, at times wearing a rove and skullcap. The photographs he also used for Christmas cards and thank-you notes.

A number of reasons can be listed for why Zahrtmann could become so popular in the press during a time, when public sentiment against male homosexuality was on the rise. If he was sexually active he kept it secretly, and he was not involved in any of the same-sex scandals of his day. His eccentricity as a private individual did therefor not offend. It became moreover a topos in the in the press that he loved his mother very much and that in her he recognized the character of Leonora Christina, the daughter of King Christian IV, whom he painted throughout his career. The press eagerly supported the cult around Laura Pauline Zahrtmann, who resided in Rønne, Bornholm. Zahrtmann’s publicized maternal affections accommodated a bourgeois understanding of the family, for which homosexuality was seen as a threat.15 Zahrtmann’s love of his mother offered an acceptable explanation for his unmarried state, which because of the historical emergence of the invert could be potentially suspicious. Another version of why he remained unmarried the writer Th. Lind offered in Almanaken in 1913:

He [Zahrtmann] does not know what enemies are. That is, unless one considers his feelings toward the opposite sex. In this light one can interpret a remark he once is supposed to have made when asked by one of his friends why he never married. ‘A couple of sons I would like to have but I do not care for a wife.’ Even though one shouldn’t always take Zahrtmann literally this still might be his honest opinion. It is possible that women are not clever enough for him […]16

The explanation for the painter’s unmarried state proposed by Lind amounts to little more than chauvinism. His insistence that only women’s presumed inferior intelligence was the reason for why Zahrtmann remained unmarried reveals the conclusion the writer deliberately was avoiding.

Androgyny, which became an integral part of discourse on same-sex sexuality during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, made its appearance in Zahrtmann’s self-representations and in others’ characterizations of him. In this respect the painter internalized the role defended for him by the medical doctors. An example is Julius Paulsen’s (1860-1940) Group Portrait of Artists from 1903.17 The artists are seated except for Zahrtmann, standing and attending to Julius Paulsen’s wife, who winds yarn held by Zahrtmann. Throughout his life Zahrtmann had extensive correspondence with friends, family, and colleagues, including the spouses of his male colleagues.18 As suggested by Paulsen’s painting, Zahrtmann’s relationship to women could be seen as marked by an intimacy familiar from friendships among women. It would be mistaken, though, in Zahrtmann’s relationship to women to see sympathy for the early women’s movement. Even as Zahrtmann’s “femininity” by his contemporaries could be perceived as unnatural it still operated within the prevalent paradigms of gender roles.

Other expressions of Zahrtmann’s “androgyny” include two occasions of festive cross-dressing. The first took place at the masquerade held in the residence of Count C. E. Frijs in the winter 1900-01on the occasion of the eightieth birthday of the artist Lorenz Frølich. Zahrtmann wore a Greek women’s costume with a large chicken head in expression of “Platonic misogyny.”19 At the ball held on 4 April 1903 by his students on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday, Zahrtmann wore the costume of a woman from Civita d’Antino.20Even as these instances of cross-dressing had their roots in the carnivals held by the student organization as part of male communal bonding, at the turn of the twentieth century such behavior had become suspicious as potential signs of homosexuality.

At different levels social nobility was connected to sexual inversion, Zahrtmann being no exception. Being from a middleclass background, there were members of the nobility in his extended family. In a written memory from his childhood printed in Tilskueren in 1913, Zahrtmann could tell how he had thrown a flower bouquet that landed in the lap of Countess Danner, who visited Rønne together with King Frederick VII on 8 September 1856.21His fondness of young noblemen became proverbial. Walter Schwartz wrote about this in Politiken in 1943:

People teased him with his fondness for counts, and in a letter he defends his position: I care for counts […] it is meant that they are born into greater freedom than many others, and if one does well to them one does well to many.22

In several of Zahrtmann’s later self-portraits he faces the beholder wearing skullcap while leaning his head slightly backward, creating an “aristocratic” effect of pathos and self-importance. These features reappear in Wilhelm Hammershøi’s portrait of the artist wearing pincers of 1889 (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), which seems to have provided the model for the portrait drawing that accompanied many of the articles published about the painter. To Zahrtmann ideas of aristocracy held different potentials. As Schwartz pointed out in Politiken, nobility held the possibility of spiritual development. Notions of aristocracy were integral to the persona of many artists during the nineteenth and twentieth century. The artist-bohemian with his claims to semi-aristocratic autonomy could become a figure of fascination to the bourgeoisie. This was also the case with Zahrtmann, who in his appearance accommodated many of the notions that defined the male invert but who also found acceptance with his bourgeois views and sober behavior. Finally, aristocracy could be tied to sexual inversion because the elite status of the aristocrat could be associated with an elevation above the accepted norms. It was the art critics who felt that Zahrtmann crossed the line for what was acceptable in a series of paintings, which in highly original ways aimed to inscribe the eroticized male body and the transgression of gender norms within classical educational ideals. In the art criticism reappears a number of the themes known from Zahrtmann’s status as a public celebrity and beloved eccentric, though here the themes were launched in an attack against his alleged indiscretion.

IV

Zahrtmann’s contemporaries did not write much about his late history paintings. They were generally unpopular among the critics, who found them to be ungraspable, and the writers’ indignation seems to have hindered a less biased art criticism. This took place in the years when his paintings otherwise were sold for increasingly large sums. I shall argue that Zahrtmann operated from the same assumptions about visual expression in his later paintings as was the case with his production pre-1900, and I shall attempt to reconstruct his intentions in his late works by studying the criticism of his works, spanning his entire career, and his own statements about art.

The key concept in Zahrtmann’s oeuvre is classicism, a striving for continuity with the past, and a desire to create novelty from inside of tradition. Notions of classicism appear in three different ways in his works: 1) In the choice of subject matter; 2) In history paintings that per definition demanded the audience’s familiarity with the textual sources; 3) At the level of pictorial style.

1) Zahrtmann operated within the academic hierarchy of genres. He executed narrative paintings based on European and in particular Danish history, Greek and Norse mythology, and the Bible, and he painted portraits of wealthy burghers, genre paintings with motifs from the Danish countryside or Italian farm workers, landscapes, and flower scenes. These genres were rooted in the tradition of academy professor C. W. Eckersberg (1783-1853) and propagated by such artists as Wilhelm Marstrand (1810-73) and Carl Bloch (1834-90).23 Marstrand had been Zahrtmann’s instructor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, from where he graduated in 1868. Zahrtmann’s Danish genre motifs, picturing life in the country as simple and unchangeable, continued a tradition from the mid-nineteenth century exemplified by Frederik Vermehren (1823-1910), also one of Zahrtmann’s teachers from the academy, Christen Dalsgaard (1824-1907), Julius Exner (1825-1910), and Bloch. Zahrtmann’s rural interiors show predominantly women in keeping with middleclass notions of the proper sphere of women. The poor Italian farmworkers in his art, practically always cheerful, he pictured as being in harmony with a simple lifestyle. The Italian scenes, however, include erotic elements absent from his contemporary Danish motifs, whereby the Italians emerge as differently motivated by their passions. The pictures reveal projections of the Copenhagen bourgeoisie regarding the Mediterranean world in contrast to their own respectability, creating a Northern European identity through the Italian Other. Such ideas appear in the works of earlier Danish genre paintings with Italian subjects. In Marstrand’s Scene from an Osteria of 1849 (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen) the beholder is invited to join the bench next to the two swarthy, young women, but the situation is ambiguous because not only must the beholder beware of the dog underneath the table, which already has noticed her/his presence, but also guard the sleeping matron seated on the bench next to the young women. In her clenched right fist she is ominously holding a raised knife.24 IIn Bloch’s variation on Marstrand’s painting, Scene from a Roman Osteria, 1866 (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), the attraction and danger exemplified by the women is no longer split in two groups as in Marstrand’s painting (young women on the one hand and dog and matron on the other) but is now entirely embodied by the young Italian women. Their flirtatious gazes reveal an awareness of the danger they present, exemplified by the feisty young man seated at their table, who has turned to the beholder with a fork in his clenched fist. The black cat on the left can be seen as comment on the double nature of the women (a motif already introduced by Albert Küchler [1803-86]). The clothing of the women with their transparent ruffles and blousing skirts displaces and fetishizes the sexual fascination that they hold.

Zahrtmann’s Three Girls Carrying Lime of 1883 (DS 541) continues the fantasy of the accessibility of the Italian women, even if for nothing else than innocent flirt [fig.1]. Their hilarity combined with the fact that none of them are looking in the direction of the beholder implies awareness of being watched by a (male) spectator. In Italian Farmers of 1903 (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm) the woman with downturned gaze lifts her dress to the sides so as not to step on it while descending the steps on the sloping, mountainous terrain. Meanwhile a man in the background with his arms crossed is staring at her. The painting thematizes the act of gazing as gendered male and libidinous while the beheld object remains passive and female.25 Italy at the turn of the century was one of the places to where Northern-European men from the middle and upper classes traveled to seek out male prostitutes. The painter’s popular Italian genre scenes do not leave any traces of this reality.26

Zahrtmann’s oeuvre offers different types of Italian subjects, including views over cities and landscapes seen from the hotels where he stayed. In these scenes he often let the foreground be constituted by the terrace where he presumably executed the paintings. He thereby marked his identity as a Nordic tourist in Italy, which always was implicit in his genre scenes. These paintings, primarily aimed at Copenhagen audiences, staged the social and cultural identity of the beholder defined through difference from the Italian farmworkers.

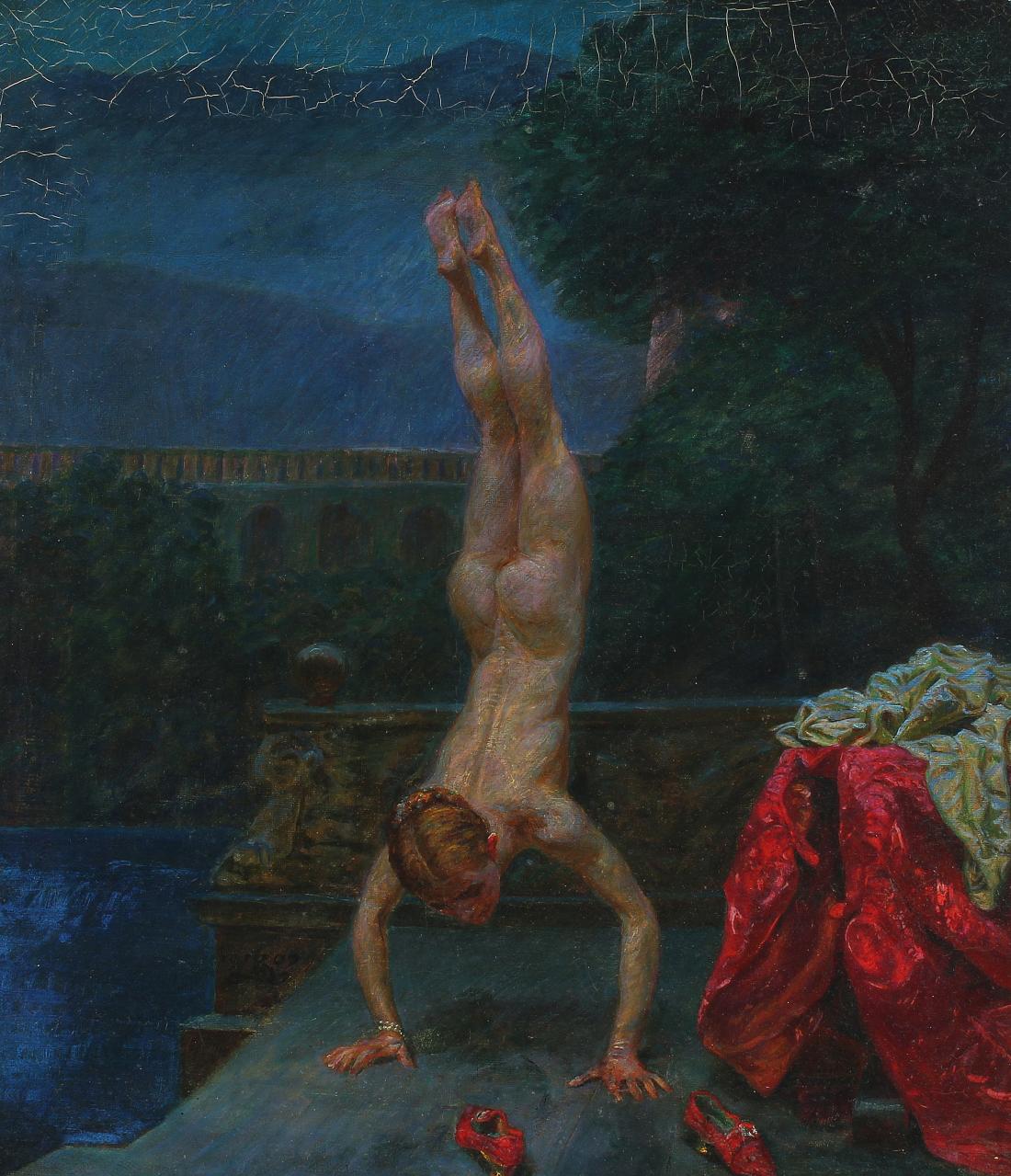

2) As a history painter Zahrtmann saw it as his task to renew and elevate the inherited art form, and he stands as one of its last exponents of importance in Danish painting. Even as he radically redefined history painting he still preserved the inherited wisdom of the genre: The inclusion of an entire narrative in a single scene. When in his later years his contemporaries had such difficulties understanding these works it was not just a result of history painting becoming rapidly outmoded. The difficulties offered by his works primarily stemmed from his attempts at innovation within the genre. He chose scenes never painted before and narratives that only rarely had been deployed by artists. Moreover, he cared little about implying what had come before and would happen after the depicted moment. In this respect his history paintings were deliberately elitist. Moreover, the artist’s intentions with his subjects were not obvious. Even though he early on was criticized for choosing ungraspable scenes he continued to paint relatively unknown stories, or he interpreted the scenes in difficult ways. Such tendencies in his art culminated late in his career in a painting like Susanna at Her Bath, 1907 (DS 989) [fig.2], where the shorthaired Old Testament heroine is doing a handstand and the two elders are nowhere to be seen.27 The painting was perceived partly as a joke and partly with indignation, especially when it became known that he had used a male model. The change of the pose displaced the voyeuristic interest from the woman’s breasts to the male model’s buttocks.

Writing in Siena on August 10, 1876 to his colleague Pietro Krohn (1840-1905), Zahrtmann commented on his painting of Samson (DS 415) (present whereabouts unknown). The work originally included the figure of Delilah, but the artist later decided to fragment the work. The youthful Samson with a golden ribbon in his hair sits naked with a cluster of grapes, on which he nibbles, held like a fig leaf. Zahrtmann explained that the work embodied the entire story of Samson as a young man pure of spirit, who throughout his life was faithful to his ideals and religion, but who repeatedly let himself be seduced by the opposite sex.28 Furthermore, in Samson the artist found parallels to King Christian II (r. 1513-23). A common denominator for many of Zahrtmann’s paintings was the pursuit of an ideal. Despite the sad fate of such characters as King Christian IV’s daughter Leonora Christina (1621-98), Samson, and Job, they were faithful to their ideals, which were strengthened in the process.29

Zahrtmann attempted to innovate history painting by making it intimate. He did so by interpreting the historical motifs in the light of genre painting, deploying few figures in an interior while emphasizing the protagonists’ psychology and emotions.30 The tendency towards the intimate in the paintings facilitated the representation of bourgeois virtues in the great figures from history. In this vein the art historian Karl Madsen described Zahrtmann’s history paintings as producing an effect as if the artist himself had been present when the scenes originally took place. By claiming that Zahrtmann was able to set himself in a heartfelt relationship to history, Madsen mobilized the artist in his attack on contemporary history painting as practiced by the academicians for the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg. These paintings he considered to capture only empty pomp and splendor.31

3) In his correspondence Zahrtmann often commented on the artists whom he considered exemplary. Writing to the historian J. L. Heiberg in 1914 he listed in the following order the artists one had to admire: Raphael, Titian, Rembrandt, Correggio, Phidias, Thorvaldsen, and Marstrand.32 Elsewhere he bestowed praise on Carl Bloch.33 Significantly Zahrtmann only mentioned older artists. Constructing a genealogy, he defined himself as the latest branch of the Western, artistic tradition. In his history paintings from the nineteenth century he accommodated pictorial style to the represented historical moment. The paintings with Leonora Christina quotes the Dutch baroque such as Pieter de Hooch regarding interiors and costumes while chiaroscuro and brushwork is indebted to Rembrandt.34 In another Baroque subject, the rejected sketch for the banquet hall of the University of Copenhagen, Students Leave to Defend Copenhagen in 1658 of 1888 (DS 620) [fig.3], the pictorial echoes are from Frans Hals.35 In the scenes from the court of Frederik VII it is the painting of the rococo that he alludes to with the frieze-like compositions and the light color with turquois, rose, and gold. This linked Zahrtmann to broader historicist trends in European painting.

In his later works Zahrtmann instead introduced a “mixed” style that preserved the theatricality of his earlier historical subjects. The theatrical to Zahrtmann meant in a very literal sense that which was like theater. For instance, his paintings have the character of a single moment taken from a longer dramatic narrative with the protagonists performing in such ways that the beholder might read action, emotion, and character through gesture and expression. Further theatrical devices in Zahrtmann’s art include the rear walls, which typically are placed relatively close to the foreground and parallel to the picture plane, like a backdrop in a theater. Finally there are few scenes he painted from theater plays (Shakespeare and Henrik Ibsen).36 The theatrical in Zahrtmann’s art can also be seen in connection with contemporary educational ideals that included the attendance of theatrical performances. As a teacher Zahrtmann tried to inculcate his students the importance of going to the theater as part of their spiritual development. He was opposed to French painting (most likely Impressionism), which he felt sacrificed everything for the effect of unity. The resulting loss of detail in turn led to a loss of the pictorial subject’s readability and thereby its theatrical effect.37 With Impressionism’s dissolving of stable form in the rendition of colored light in constant flux, the unambiguous spatial definition of objects was deliberately weakened. Avoiding the dissolving atmospheres of French painting, the painter turned to other means of communicating the pictorial subject and engaging the spectator. For this purpose he explored the theatricality of the regional tradition, of Marstrand and Bloch.

Zahrtmann distanced himself from French art in favor of a more classical experience of form while utilizing baroque painterly techniques with generous use of impasto. Still, his deployment of complimentary colors such as yellow lights and purple shadows reveals his awareness of Impressionism.38 Zahrtmann’s color would increasingly develop a luminous, jewel-like effect while his last works, atomizing the elements of color, are reminiscent of Expressionism.39 To Zahrtmann classical form had a spiritual potential in the ability to represent universal qualities. Against this approach to art stood the contemporary “spiritless” realism and Impressionism.40Constantin Hansen (1804-80), one of Zahrtmann’s artistic models, expressed in 1863 his artistic ideals in writing, which might be attributed to Zahrtmann as well. With veiled reference to modern French painting Hansen had the following to say about photographic illusionism in relation to painting:

The delicate movement of line, the delicate play of light and shadow, and the mutual relationship between these are the means whereby the characteristic, the beautiful, and the soulful become visible. This the uneducated eye only unconsciously feels. This is exactly what art captures from the world of movement and grabs hold of, not like a photographic mirror but as a harmonious and rounded whole, which has come into being through consideration and perception, understanding and selection […] It is not by way of a stereoscopic disappointment that art takes us into the world of beauty. The artistic illusion will only awake the beholder’s curiosity. Just as little as a drawing or copper engraving makes claim to illusionism so is the case with painting and sculpture.41

Constantin Hansen also believed that painting and sculpture served the same purpose, the enrichment of the spirit and the revelation of the ideal in the visible world. He emphasized that art had to balance equal parts realism and idealism, even in a portrait. When only the first was present the result would be spiritless and photographic, and if only the second was present the outcome would be mannered and devoid of character.42 The art theoretical themes that Zahrtmann can be seen to have shared with his older colleague include figure painting as the foremost goal, the distancing from a “soulless” photographic realism, and a belief in the ability of classical form to convey spiritual content beyond the visible.

The art historian Wilhelm Wanscher compared the later Zahrtmann with Symbolists such as Harald Slott-Møller (1864-1937) and J. F. Willumsen (1863-1958). Wanscher saw these painters as exponents of an anti-naturalistic classicism or “stylism” (stilisme).43 As a proponent of the classical ideal in modern art, Wanscher in his review of Forårsudstillingen [the annual exhibition hosted by the Art Academy of Copenhagen] in 1904 identified in works by H. Slott-Møller and Zahrtmann a return to an eternal ideal, which had been ousted with the arrival of naturalism.44

I shall consider Zahrtmann’s A Roman Stucco Worker of 1886 (DS 577) as a metaphor of his artistic project [fig.4]. The relief being copied by the Roman artist, seen against the light source from behind, is Thorvaldsen’s Dance of the Muses on Mount Helicon.45 The stucco worker can be seen as a figure of the painter, whose activity resembles a painter handling a brush in front of a canvas. This connection is enhanced in the more painterly second version with broader and more marked brush strokes, which Zahrtmann executed the following year (The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen). In the stucco worker’s act of copying, the classical tradition is repeated in the artist’s presence. By letting a Roman artist copy a Danish neoclassical relief with its imitation of ancient form, Italian, Danish, and Greek traditions connect across time in the present moment of the painterly act. Sculpture is inscribed in the painterly tradition as Zahrtmann draws coloristic inspiration from the white plaster.46

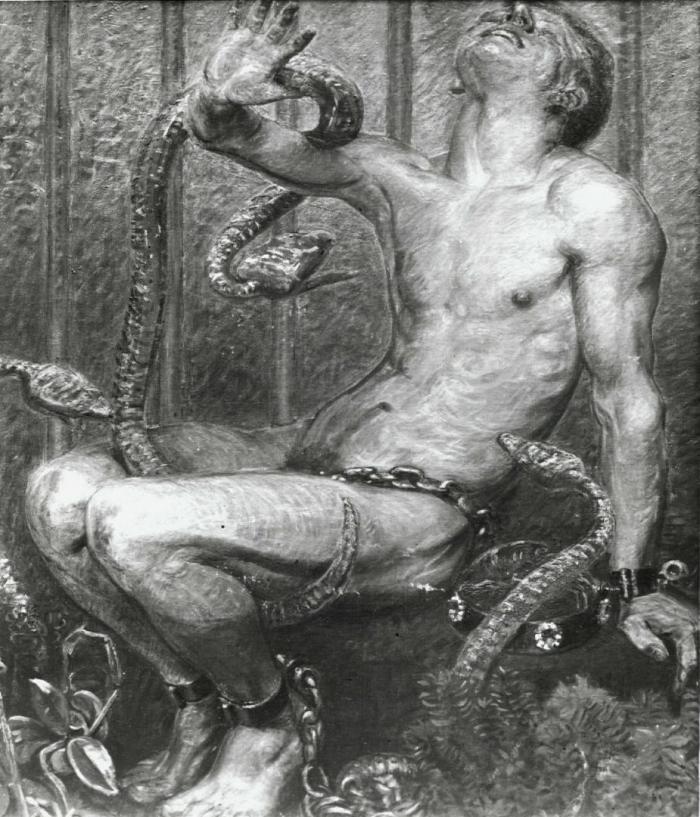

Not only through stylistic imitation did Zahrtmann aim at making historical ideals present. He also staged great historical characters in the present. This took place in the series of cross-references between individual works. In this light his Prometheus of 1904 (DS 943) appears on the walls inside several of his other paintings [fig.5]. The painting was the first of a series of nude males, which Zahrtmann painted in the twentieth century. The subject connotes European cultural heritage and classical educational ideals, and it has such predecessors in Danish painting as Bloch’s monumental Liberation of Prometheus of 1864 and the murals with the legend of Prometheus by Constantin Hansen in the Vestibule of the University of Copenhagen, 1845-47. After having stolen fire from the gods to give it to his own creation man, the titan Prometheus is chained to the Caucasian rock. In Zahrtmann’s painting Prometheus is lifting his right arm to avoid the attack from the eagle, which has come to take his liver. With an expression of resignation he bends his head while placing his left hand against his chest.47 The punished titan was a common image of the artist, and in 1917 Zahrtmann executed a self-portrait (DS 1189) with the painting in the background [fig.6]. As the artist lifts his left arm towards his chest (his right arm if the work was executed with the use of a mirror) he repeats Prometheus’s gesture.48 Prometheus marks a new phase in Zahrtmann’s art in which the male nude would play a leading part. The realistic rendering of bodies, recognizable as having been painted after models, fits into the artist’s idea of renewing tradition and making it present, the male nude to the artist being a carrier of cultural traditions rooted in ancient Greece.

Leonora Christina and Dina Vinhoffvers of 1910 (DS 1030) (present whereabouts unknown) shows Vinhoffvers attempting to warn the king’s daughter of her impending imprisonment, which, however, she accepts. On the left can be seen one of Zahrtmann’s own statuettes, Leonora Christina Leaving Prison, like a prophecy of what is to come. The seated Leonora Christina is holding a painting, as if she were contemplating it at the moment she was interrupted. On the back wall hangs Zahrtmann’s Prometheus, whose fate is then linked to the sufferings of Leonora Christina as a result of her faithfulness to her husband Corfitz Ulfeldt, who committed treason. In Leonora Christina and Dina Vinhoffvers the contemplation of art becomes part of an educational process, shaping the subject towards an ideal.

The theatrical in the late history paintings allowed Zahrtmann to draw connections between different chronological and geographical spheres in the expression of a shared ideal. In this light the paintings can be recognized as having been staged in Zahrtmann’s studio, the protagonists posing in costume with occasional modern hairstyles, as if the historical ideal reemerged in the presence. In this context one can see the painter’s abandonment of the eclectic deployment of styles relating to the represented historical moment in his pre-1900 oeuvre. It is as if the painter came to realize that the existence of past ideals in the presence could better be communicated in a style that contained a plurality of past pictorial idioms. With this he could set forth all historical subjects. His late style paid homage to a multiplicity of past artistic styles, emphasizing their cohesion.

The attempt to picture the continued presence of an ideal across history was already present in his earlier history paintings, which some critics thought ineffective because of anachronistic details and the repetition of elements from his previous production, undermining the historical illusion. An informative example of his deployment of anachronisms in his later production is the The Prodigal Son of 1909 (DS 1017) [fig.7]. The son, who has wasted his inheritance and apparently lost all his clothes, is united with his white-bearded father in a tender embrace while the disapproving brother on the right holding a waterpipe watches them. The room is recognizable as Zahrtmann’s studio in Amaliegade with the embroidered screen with the pageboys on the left and a mask of Leonora Christina on the table, which is covered with a wool carpet from Bornholm. The Egyptian relief on the table together with the costumes and waterpipe connote the Orient. Behind the relief can be seen a large painting in one of Zahrtmann’s characteristic gilt frames in a fantastic version of Danish renaissance style. At the extreme right one recognizes yet a statuette representing Leonora Christina Leaving Prison. The Orientalist flair of the rich ornament and detail connote the biblical setting and, characteristic of the late history paintings, the setting is recognizable as Zahrtmann’s studio, where all historical periods are enacted. Even as the painting is startling in the highly unusual combination of nude and dressed men inside a boudoir-like interior, it quotes two prototypes from Danish art. Zahrtmann thereby shows himself as the innovator working within a tradition of Danish painting art, centered on figure painting. The sources are Wilhelm Marstrand’s two versions of the Return of the Prodigal Son, taking place inside a contemporary Jewish home, and Holger and Jørgen Roed’s same subject, where the visibly moved fader at the entrance to his home approaches the nude, crouching son.49

V

The late paintings centered on the male body set forth a homosocial sphere. In order to approach this aspect of Zahrtmann’s art I shall examine some of the meanings attributed to male communities at the turn of the twentieth century. Elaine Showalter among others have pointed out that the rising women’s movement and the attempts by women at entering traditionally male institutions such as universities were by many men considered a threat to society at large.50

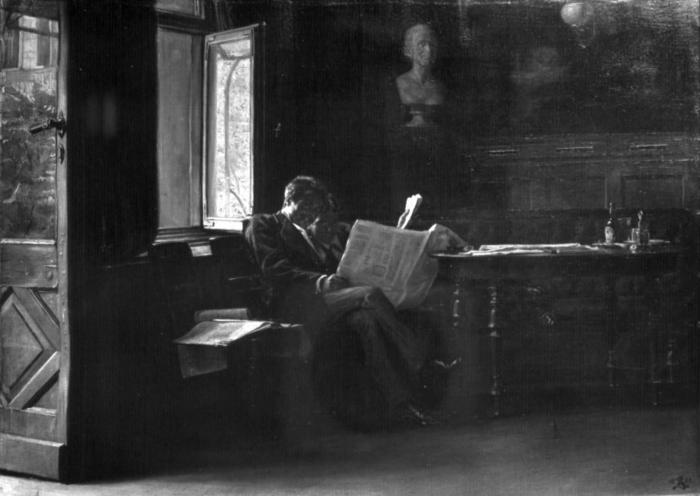

In this respect Zahrtmann seems to have had very traditional views since women did not have entry to his school of painting. One of his earlier works, Scene from the Students’ Association from 1882 (DS 526) [fig.8], show two younger men who in close vicinity grinningly looks up from their newspapers. The table in front of them with beer bottles and papers in relative disorder show manly relaxation and the absence of any “female” sense of order. The scene takes place in the reading room of the Students’ Association’s former location at Gammelholm, where H. W. Bissen’s copy of Thorvaldsen’s bust of H. C. Andersen could be found. In the painting it appears above left.51 DIn 1877 the first two women matriculated at the University of Copenhagen followed by two more in 1880 and again two in 1882. Numerous older students, who thought of the Students’ Association as their second home, were concerned that if women were permitted entry the social atmosphere of the organization would cease.52 Zahrtmann’s painting with the students from 1882 might therefore be seen to position itself in relation to the debated topic of male institutions and women’s rights. The homosocial sphere painted by Zahrtmann had by then become problematic in more than one sense. Not only was there the external “threat” from matriculated women by also the rumors that had flourished few years before Zahrtmann painted the image of sex between men among members of the Students’ Association.

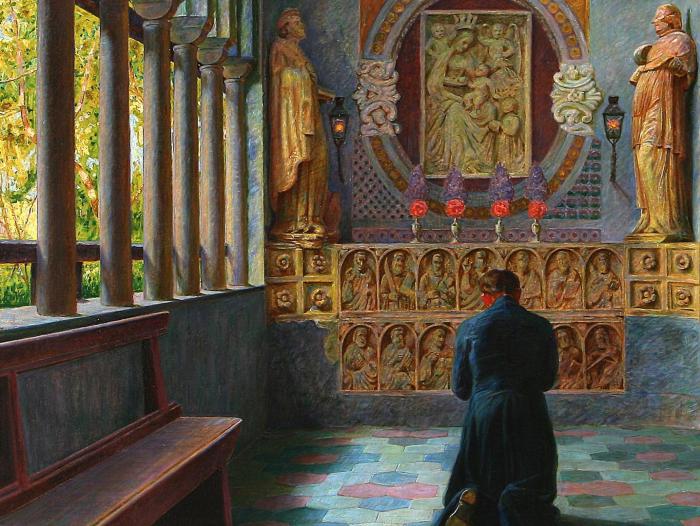

Zahrtmann produced only a single genre painting of a Danish, male homosocial sphere but painted numerous scenes with the chaste, male community of the Italian clergy. The artist was fascinated with the rituals, mysticism, and beauty of Catholicism.53 Often he would picture young priests in the act of praying, reading, or playing music inside a church. These activities may be seen as metaphors of the immersion in art. In the Kneeling Priest, Amalfi Cathedral of 1907 (DS 992) the venerated altar is also a work of art with its stone reliefs [fig.9], and as in A Roman Stucco Worker the back turned figure becomes a repetition of the artist/beholder’s presence in front of the canvas. The representation of the absorption in prayer has much in common with the semi-sacred notion of art as exemplified by the Symbolist Movement.54 The spiritual nature of both prayer and the contemplation of art is emphasized by the fact that the priest’s head is turned downwards. Hence he is not looking with his physical eye.

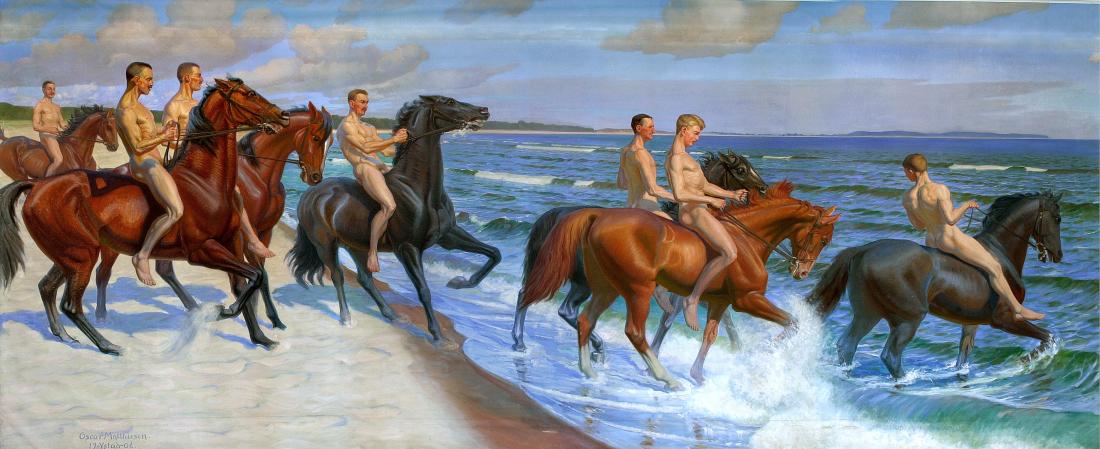

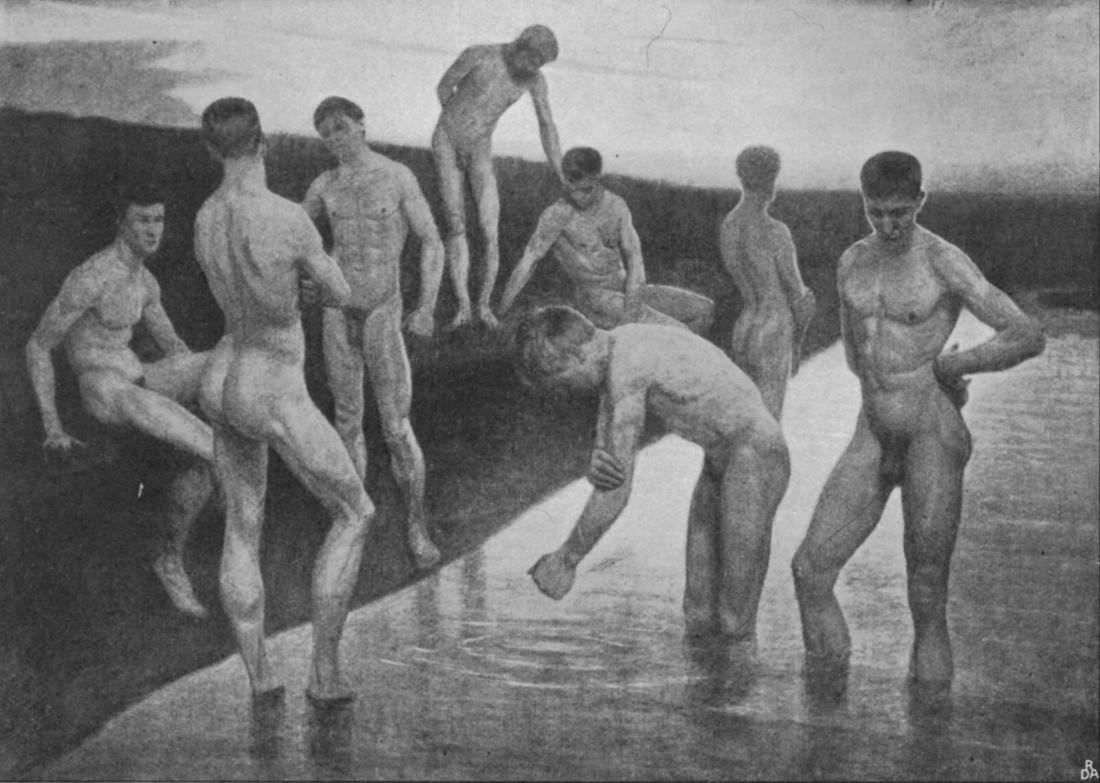

It seems significant that the worship of art takes place inside a male world. Zahrtmann’s history paintings with nude males have some shared features with a contemporary phenomenon in Danish art known as Vitalism. These works showed young nude people and children, often only male, in the outdoors.55 In these works nudity was closely associated with notions of both mental and physical cleansing of the “degenerating” influences from civilization. This comes across in the ecstatic language of an admiring critic of Oscar Matthiesen’s (1861-1957) enormous Officers of the Scania County Dragoon Regiment in Ystad Ride into the Sea to Bathe on a Sunday in June of 1906 at its exhibition at Charlottenborg, Copenhagen [fig.10]:

What the artist intended is a glorification of health, of strength, of joie de vivre, of beauty. For that purpose he took of what he needed from Antiquity, from the Renaissance, and everything beautiful and healthy in nature as pleased the artist’s eye. These are animals and humans of pure race; he has painted Swedish noble officers, who cultivate their bodies as if they were sanctuaries. The animals are thoroughbred, and the artist needed the large, the enormous to express how high above common and plain realism he has thought and felt his subject.56

The review demonstrates how this type of painting could be interpreted as tokens of ideal patriarchy that calls attention to race and class. Matthiesen’s painting is related to the contemporary culture of athletics in Denmark where people of the same sex socialized in varying degrees of undress, atypical for society otherwise. Sport in itself was to guarantee that such situations were not of a sexual nature, and the contemporary literature on athletics emphasized that physical exercise would make the young man more resistant to carnal desires.57 Among the works of art in this genre belongs Evening: Bathing Boys, 1905 by the Zahrtmann pupil Vilhelm Tetens (1871-1957) [fig.11].58 The act of cleaning is the focal point of the composition with its meditation on ideal physiques. The figures are connected though similarities of poses and body types, but gestures and expressions separate and isolate the protagonists from each other. Some characters with bent heads are narcissistically absorbed in their own doings and thoughts even as their poses are addressed to their surroundings. Other figures seem to threat or challenge one another such as the standing pair on the left. The frontally placed youth holds his arms slightly away from his body, his one visible fist being clenched. The back turned figure instead crosses his arm over his chest and looks at the other protagonist with his head leaning slightly backward in an expression of distance. These boys create space around themselves as they challenge one another and turn themselves into objects for their surroundings in order to objectify them in return. This happens in the attempt at impressing the surroundings with their masculinity, provoking a desire to embody similar gendered qualities. The male ideal, to which Tetens’s painting is geared, was characterized by anti-homosexual emotions, which can be understood in the light of the historical emergence of a male homosexual identity. Tetens built this complex into his composition in expressions that are distancing, excluding the possibility of sexual contact between the bathing youths. The way in which the painting formulates relationships between men demonstrates that the awareness of homosexuality influenced the masculine ideal as an unavoidable problem that had to be negotiated.59

VI

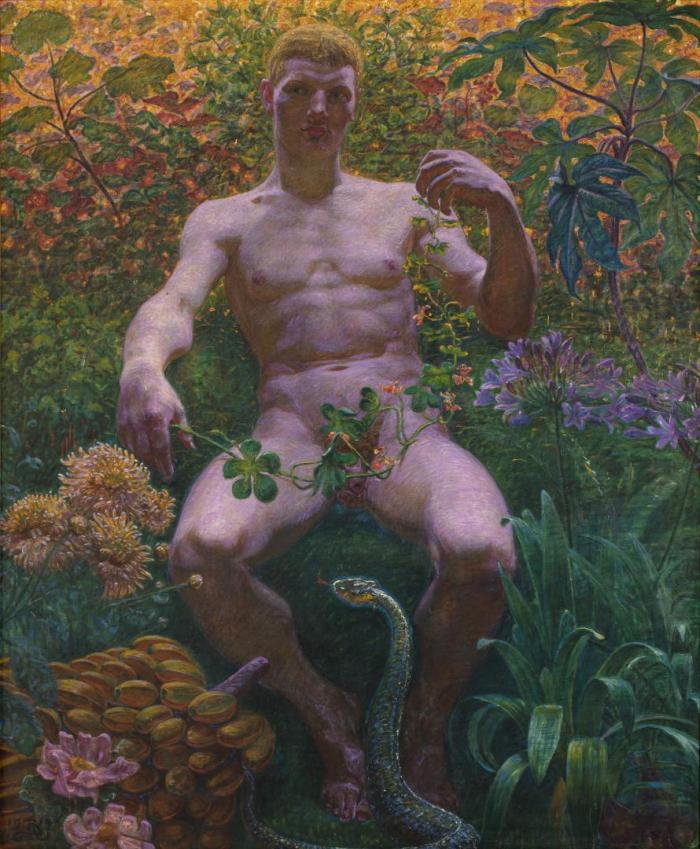

Zahrtmann’s representations of the nude male differed from the Vitalist works created by his pupils by being literary history paintings while sharing the glorification of the male body and the homosocial sphere. The major difference between the works by Zahrtmann his and students at Studieskolen was his sexualizing of the male body. In 1914 Adam in Paradise (DS 1101) was the most sensational painting featuring the nude male at Den Frie Udstilling in Copenhagen [fig.12]. He also created a smaller study for the work without the snake (DS 1102) (present whereabouts unknown), also exhibited on that occasion.

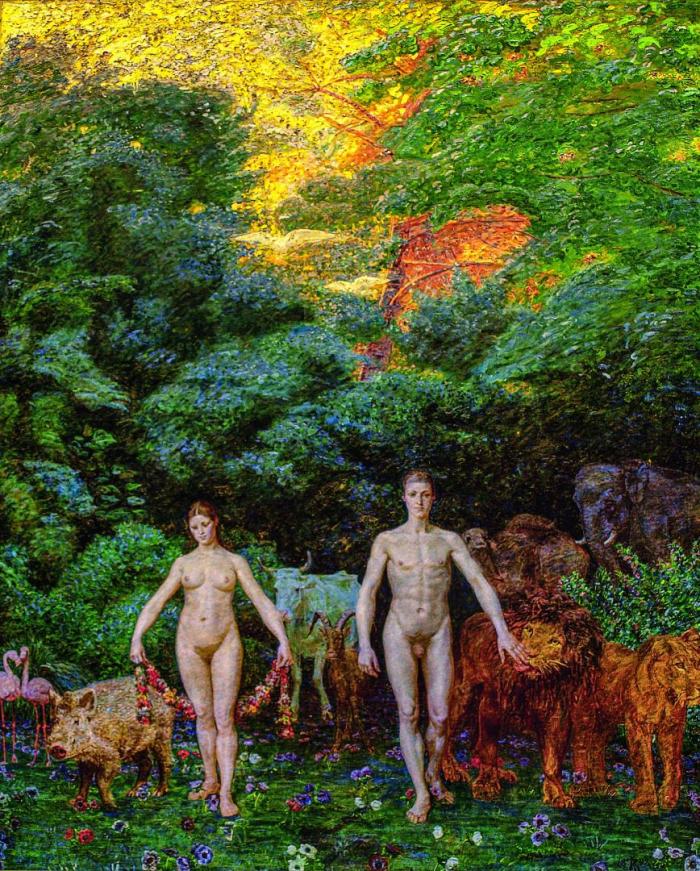

Zahrtmann’s paintings of Paradise forge bonds to the artistic past, Marstrand included. The sparkling yellow light shining through the leaves above in the larger Adam painting is a compositional repetition from Adam and Eve in Paradise of 1892 (DS 717) [fig.13], while the figure of Adam, revealing the use of a model in its realism, also recalls the art of Antiquity and the Renaissance. Michelangelo’s David, 1501-04 (Florence, Galleria dell’Accademia) in particular comes to mind regarding the anatomy with the strong arms and the modeling of the chest together with the placement of the arms, the right one lowered and the left hand raised in front of the shoulder. Whereas the attention of David with his turned head evades the beholder, Adam’s gaze is turned to his right. Even as he is frontally placed and hence oriented in the direction of the beholder, his gaze makes him inattentive to the audience. Nonetheless the string of foliage that he is holding in a less than successful attempt at concealing his genitals reveals an awareness of being beheld. While this duality is typical of the theatrical structure of Zahrtmann’s works it also eroticizes the nude, since the gaze of the beholder is “assisted” by the non-confrontational gaze of Adam, by the piquant “loincloth,” and through his frontal position with spread legs. The distancing effect of the nudes as seen in Tetens’s Evening: Bathing Boys has been substituted with a pose of relaxed passivity. When eroticizing the figure the painter turned to contemporary representations of women. Zahrtmann painted several motifs with Italian women asleep in greengrocer’s shops, and the Adam painting share with these works the fertile surroundings, the almost sleepy pose, and the sense of bodily weight. The bananas and the snake are displacements of his virility. The animal has a further function by enacting the movement of the beholder’s penetrating gaze by connecting her/his space with that of the representation.

Zahrtmann’s success in rendering a passive and eroticized male figure accounts for the attention that the painting received from the art critics as opposed to the largely overlooked Loki, discussed below. I shall here consider to of the more indignant responses to the painting:

Zahrtmann is the giant among the artists of Den Frie Udstillling. Despite his seventy-one years his lovely colors with their youthful energy puts the young painters to shame. But his ideas can also be marked by a certain youthful simplicity, such as his Adam. We recall that the snake came into his life before he learned ‘in the sweat of his face to eat his bread.’ But this athlete seems to have been trained through hard physical labor as seen in the muscles of his legs and neck and his hands, which belong to a workingman. We also learned that the snake sat on a tree trunk and that Eve was present, and we presume that this is a puzzle and seek her among the voluptuous aralias, kannas, chrysanthemums, and bananas. Perhaps the painting shows a later meeting with the snake. It may be that they are discussing the Fall of Man and its consequences, unless the snake is a symbol of Eve! 60

The art critic’s humor covers his embarrassment over the absence of Eve. Her presence could have defined the painting’s eroticism as heterosexual by letting it be played out between a man and a woman rather than between Adam and the snake/beholder. The critic’s suggestion that the snake stands for Eve emphasizes the animal’s status as the sexual counterpoint of Adam.

The journalist Helge in Politiken did not have the same ironic distance as the critic quoted above. Here the painting’s sexuality led to an attack on the artist’s apparent lack of discretion:

Today the guests at the opening of the exhibition will be staring at Father Adam while Zahrtmann with a countess at his side will be saying peculiarities […] His ‘Adam in Paradise’ is attention-seeking enough.61

The effeminate and the fascination with nobility, which was cultivated by journalists when interviewing the artist, was here brought into play as a way of criticizing Zahrtmann’s attempt at setting himself above the norms of respectability regarding gender and class. The writer responded to what he considered to be an inappropriate public display of the artist’s sexual perversion.

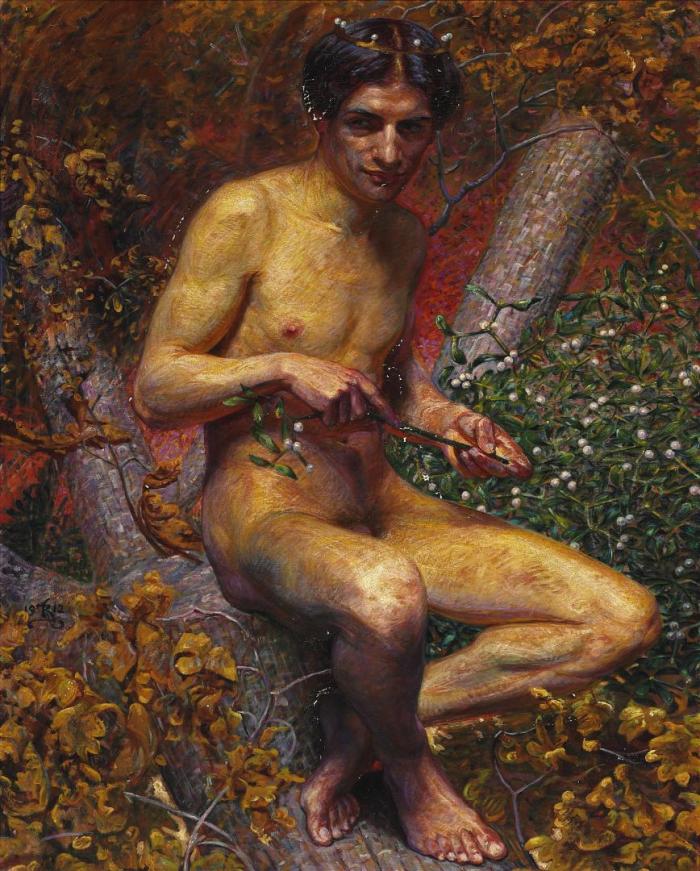

In the largest of the paintings from 1912 featuring Loki (DS 1067) he is sitting in a tree testing the mistletoe [fig.14], which he later will lure the blind Hodr to shoot against Baldr, thereby killing him. Only wearing a coronet, his spread legs and crossed feet might bring to mind Adam in Paradise. His turning away from the beholder, however, emphasizes the covertness of his activities as if trying to hide something. Loki is the wicked seducer of Hodr, but his act will lead to his own downfall. He is swarthy with a sinister facial expression, which can be understood in the light of racist ideology when the figure is compared to Zahrtmann’s ideal, blond male figures from the same period. In Loki Zahrtmann used conventions for the representation of evil femmes fatales, both attractive and dangerous. The fleshiness of his naked body is in contrast to the prickly mistletoe surrounding him, as if one were at risk of feeling pain upon approaching him. The painting did not receive much attention by writers nor was it particularly popular, but it is striking that two art critics compared the model to a woman. The objectification of the male figure apparently resulted in some form of sex change. An anonymous journalist had the following to say about the painting the year in which it was exhibited at Den Frie Udstilling:

His large painting at Den Frie Udstilling is Loki showing a beautiful male with an effeminate face, which so strongly brings to mind one of the best known among [Valdemar] Irminger’s previous models […]62

A more negative critic had the following to say about the painting:

His [Zahrtmann’s] major work this year is Loki testing the mistletoe. Previously he has used male models for female figures, but this time he seems to have used a female model for a male figure. The unpleasantly brass colored Loki has been placed in a purple tree, and that is all there is. The rest of the painting is filled with monotone flowers and leaves, as if the painter had grown tired.63

Other works by Zahrtmann deal with desire and sexuality between men at the level of iconography and literary content. This is in particular the case with the two versions of Socrates and Alcibiades from 1907 (DS 990) and 1911 (DS 1044). Erik Brodersen has characterized Zahrtmann’s use of classical antiquity in the following terms:

As a ‘Greek’ like [Georg] Brandes, Zahrtmann felt drawn toward ancient Hellas. This was partly because his sexuality had been permitted in this culture, and partly because he there identified a society that centered on the spiritual development of men.64

Apart from medical texts, some of the only available descriptions of erotic love between men at the turn of the century were Plato’s Symposium and the dialogue Phaedrus, which became the “bible” of homosexuals.65 In the Symposium the love between men becomes a vehicle for a gradual process of insight into heavenly matters, explained by Socrates. Love is here given a spiritual dimension as the older man’s affections for the younger is not motivated by carnal desire even as this is not negated, but by a love for the growing spirit of the youth, developed through their relationship. As becomes clear from Socrates’s discourse, love for the beautiful male body was only the first step in the Platonic philosophy of love. The interpretations of Plato’s writings by homosexual men permitted them to connect with the patriarchal and misogynistic ideas of a society that stigmatized homosexuality. With their emphasis on spiritual development and education in a homosocial context, Zahrtmann’s images of the male body might be interpreted in a similarly “Platonic” key as in the Prometheus, where the display of the nude male body is expected to lead to a contemplation of the entire story of the titan. While Zahrtmann’s images indeed can be interpreted in this light, there is more at stake in his works regarding the contemporary construction of homosexuality.66

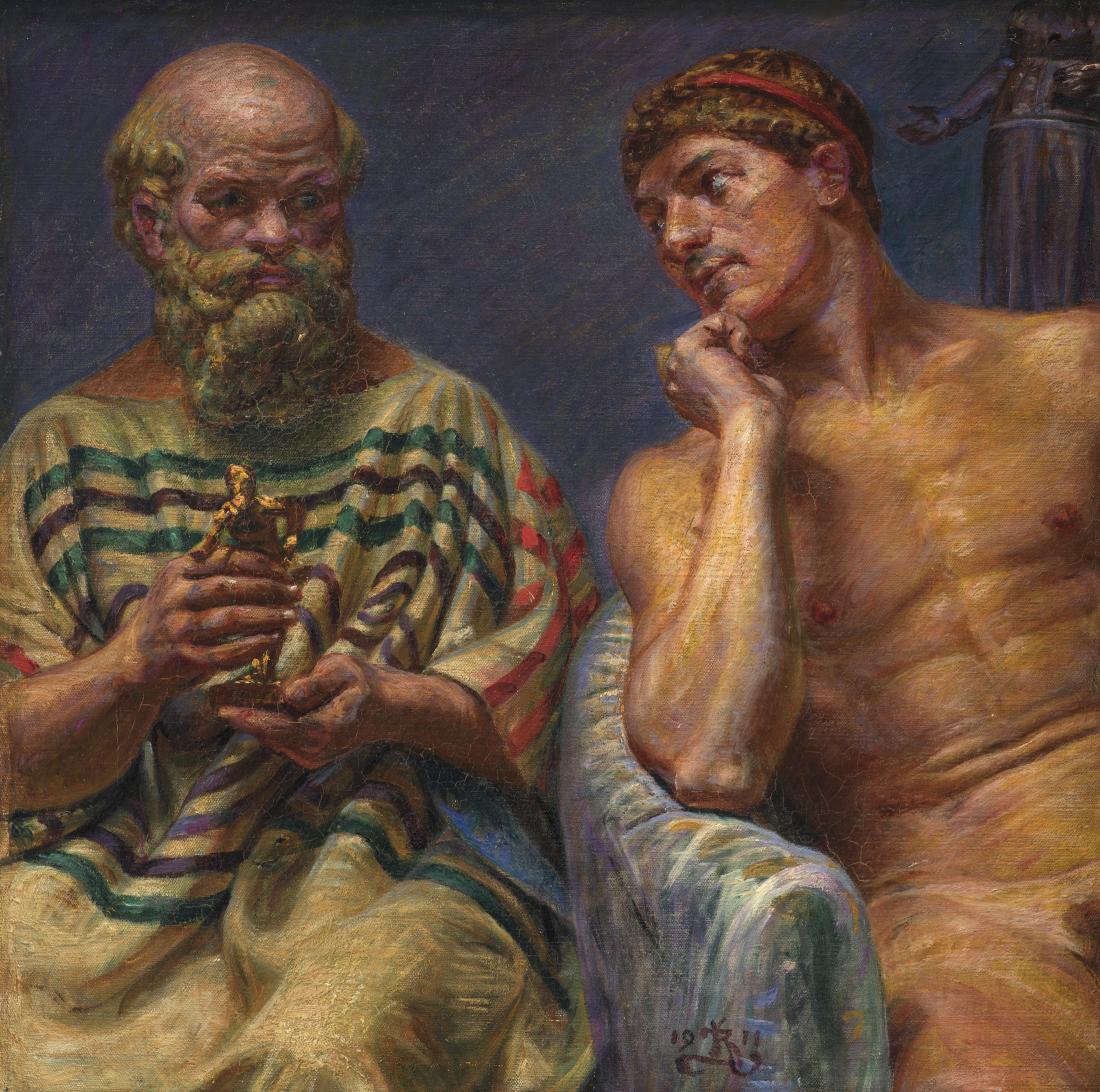

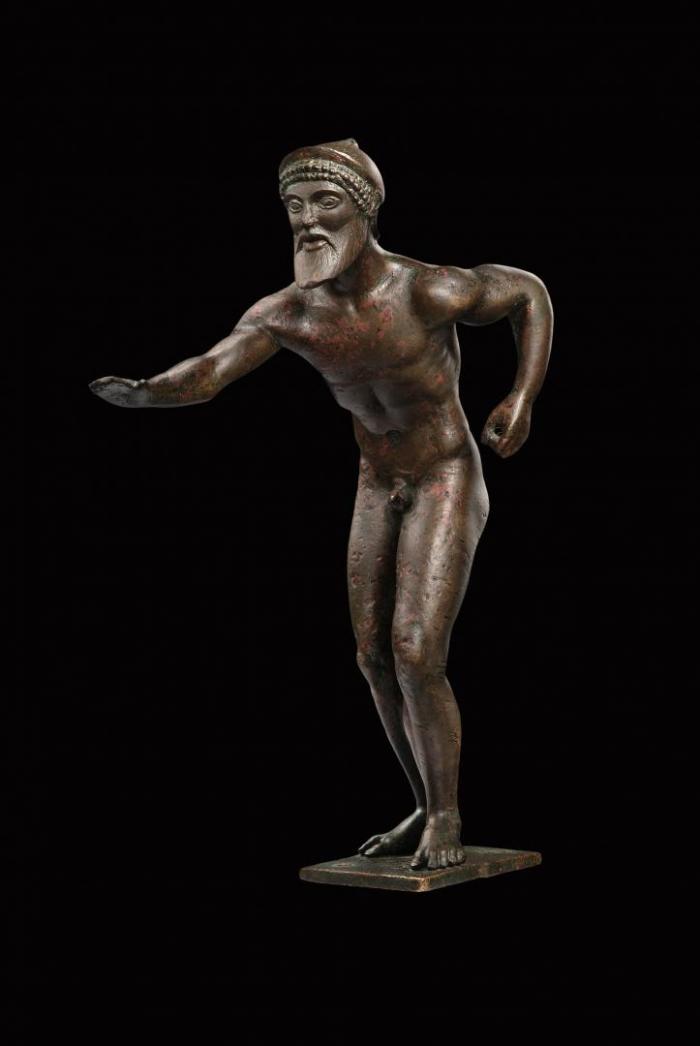

Socrates and Alcibiades of 1911 communicates sublimation [fig.15]. The nude Alcibiades sitting in what resembles an armchair gazes at Socrates as he is carried away by the older man’s discourse. Alcibiades’s frontal pose, backwards leaning, and spread legs would reappear three years later in the Adam paintings. Socrates holds a figurine with an athlete in movement [the Tübingen Hoplitodromos Runner as kindly identified by Jan Zahle, fig.16] staring into space with a thoughtful expression.67

The daring aspects of the image, – the realistic appearance of the figures including Alcibiades’s pubic hair – hint at Greek love and sex between an older and a younger man. The composition balances but does not cancel these aspects of the painting. The beholder’s gaze is led from Alcibiades to Socrates, who represents a spiritual principle, while the statuette can be taken for the union of body/matter and spirit, evoking the union between the physical and the spiritual in Socrates and Alcibiades. In the upper right corner appears the lower part of Zahrtmann’s Leonora Christina Leaving Prison. The configuration of the Danish princess and Platonic subject makes analogous the scenes from ancient Greece and seventeenth-century Denmark, both being narratives of spiritual growth. Seen in a different light the painting combines elements characteristic of the male homosexual’s self-representation at the turn of the century with Greek love and the tragic – though mildly absurd – grand dame.

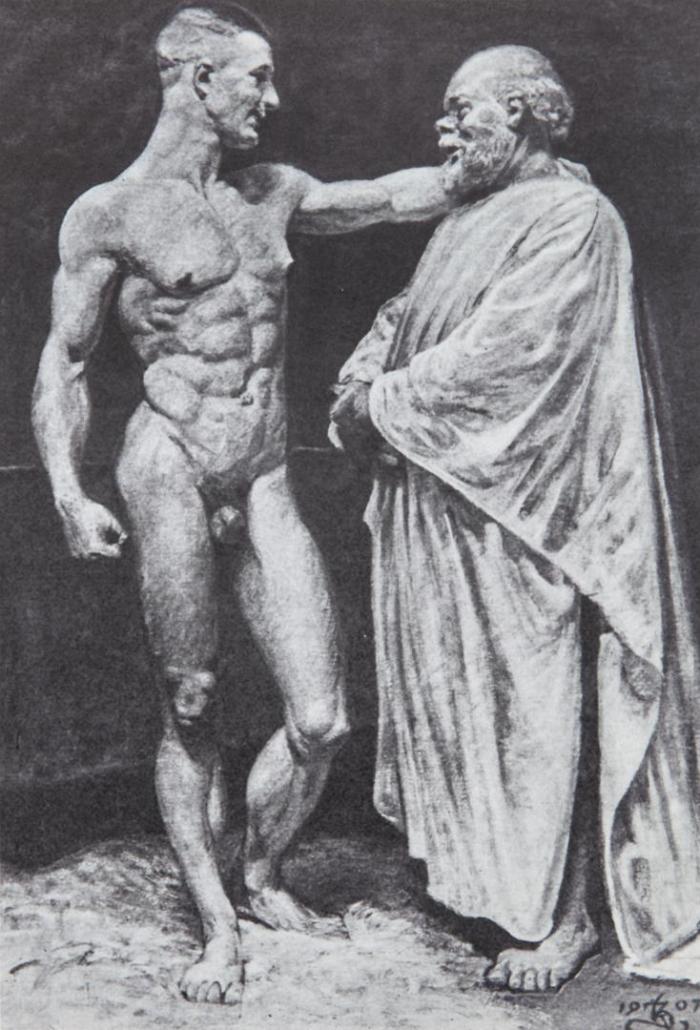

The situation is different in Zahrtmann’s earlier version of Socrates and Alcibiades of 1907 [fig.17]. The motif derives from the Symposium. During the gathering at the house of Agathon the drunk Alcibiades expresses his jealousy towards Socrates, whose intellect he desires. He has repeatedly attempted to seduce the philosopher, hoping in that way to receive his wisdom. Socrates avoided Alcibiades’s attempts at getting him into bed because that in itself proved Alcibiades’s lack of the maturity necessary to receive Socrates’s educational love. The painting shows one of Alcibiades’s attempts at seduction by doing gymnastics, nude according to Greek custom, with Socrates.68 The smiling, ripped Alcibiades has placed an arm across the portly older man’s shoulders, who, wearing a loosely fitting Greek costume, rests his hands in front of his belly. The artist painted the philosopher’s face in accordance with ancient portrait busts, one of which (or a later copy) was placed in Zahrtmann’s studio. Socrates is talking in contrast to the kind of intercourse, which the silent Alcibiades is trying to mobilize by displaying his body.

Even as the represented story tells of Alcibiades’s failed attempt at seduction, it is clear that Socrates’s resistance is not without an element of enjoyment. The philosopher is seen from the side, his nonathletic corpus hidden underneath his clothes. By contrast Alcibiades is resting on his right leg in front of the bent left in a classical contrapposto, his pose being as much directed to Socrates as to the beholder. Hence the gaze of Socrates is made parallel to that of the beholder. The behavior of Alcibiades approaches that of the prostitute, trying to seduce not out of desire but for gain. Socrates, who well understands the situation, becomes a “dirty old man.” The represented desire relates to a stereotypical understanding of sex between men with an older gentleman from the middle or upper class seeking a younger and physically well-developed working-class man, which could lead to prostitution. As suggested above the homosexual role would be reserved for the paying part, and in the painting is Socrates who is slightly effeminate, being reminiscent of an elderly lady in keeping with the gender crisis attributed to the invert. Bjarne Jørnæs has called attention to the similarity between Socrates as painted by Zahrtmann and the artist,69 enhancing the sense of the painter’s infatuation with the model.70 By letting Socrates play the part of the artist/viewer and Alcibiades the object, Zahrtmann took an ironic approach to the male body as a means of spiritual growth by evoking its ability to arouse physical desire. His painting from 1907 of Platonic love makes comic the desire for the male body since Alcibiades attempt at seduction is suspect. The humorous aspect might be seen to lend the image a certain respectability, yet it is exactly what is problematic in the depicted interaction between the two that sustains the sexual desire.

In connection with the cliché of the male homosexual’s desire for the working-class man it is of interest that the anonymous critic in Hver 8. Dag ironically described Zahrtmann’s Adam as accustomed to hard physical labor. Zahrtmann described in a letter how he came across the model for the picture in a train compartment for soldiers.71

Most certainly we are on the sunny side of life, and I was surprised to come across the train compartment for soldiers. Here I met Adam, bored amongst the wonderful, intoxicating fragrance of flowers, seated limply with no clue of the approaching birth of Eve. I long for his coming tomorrow, when I shall enjoy him as if I were in Paradise, from 8:30 am to noon.72

VII

Zahrtmann’s late paintings featuring the male body with their emphasis on tradition and culture in a homosocial sphere might be seen as expressions of male chauvinism at the turn of the century. It should be recognized, though, that the artists simultaneously operated with femininity as a category that could transgress bourgeois norms of proper behavior of both women and men. I shall limit my analyses in this respect to a single painting, Queen Christina of Sweden in Palazzo Corsini, 1908 (DS 1003) [fig.18]. Unlike his very popular paintings of Leonora Christina,73 this work became somewhat of a scandal. Before considering Zahrtmann’s Roman subject I shall address his very popular paintings of Leonora Christina, to which the scene with the Swedish queen is related.74

Zahrtmann’s scenes with the daughter of King Christian IV must be considered in the context of the general popularity in Denmark of art that represented the history of the fatherland. Brewer J. C. Jacobsen’s commissions for paintings for the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle exemplify this trend. The museum was a monument to the recently constituted nation-state, which sought justification through pictorial representations. Zahrtmann painted his first work showing Leonora Christina in connection with a competition (den Neuhausenske konkurs) hosted by the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. The task of the participants was to execute a work with a scene from the Jammersminde, the autobiography of Leonora Christina written during her imprisonment, republished in 1869. Zahrtmann’s numerous works of art based on her life shows her as the woman who remained faithful to her ideals and, because of her love for her husband, went through much hardship while keeping her dignity.75 One might claim that there was nothing progressive about the version of femininity offered by Leonora Christina to the late nineteenth century, and significantly Amalie Skram, a writer active in the new women’s movement, had nothing pleasant to say about her person and Zahrtmann’s fasciation with her.76 The paintings’ appeal to bourgeois sensibilities did not diminish when Zahrtmann informed the press that in the Danish princess he found an image of his mother. At the same time Leonora Christina, through her participation in intellectual activities, transcends the otherwise closed, masculine universe of Zahrtmann’s art. Leonora Christina was primarily remembered as the author of an autobiography. In Leonora Christina and Dina Vinhoffvers she seems to have been in the act of contemplating a work of art before paying attention to Vinhoffvers. She also appears in the form of the statuette in Socrates and Alcibiades of 1911 and both as mask and statuette in the Prodigal Son of 1909. In this way she enters the masculine sphere of spiritual formation in the images with the nude male. In this way she transcends the female gender role, which otherwise emerged from an examination of Zahrtmann’s genre scenes, his late paintings of the nude male, and his own statements. When painting her as an elderly woman he showed her as a large, almost masculine figure with hips so broad that it challenges what is anatomically possible. Zahrtmann’s pictures with Leonora Christina reveal a homosexual attitude or sensibility towards gender, rooted in traditional ideas but also transgressing these by defining them as roles. This makes possible the presence of irony and theatrical exaggeration. The mental androgyny of the invert continued the gender roles ad absurdum.

If the strange aspects of Zahrtmann’s take on Leonora Christina could be seen to support bourgeois norms of femininity, the situation was quite different with Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini. The painting shows the Swedish queen as center her of court in Rome after her abdication, where she continued her studies of the liberal arts. She is surrounded by predominantly younger courtiers. The older one among these is holding a statuette for her to contemplate, which she inspects with raised chin, since she is smoking a pipe. Leaning forwards, she makes sure that her rear end is close to the burning fireplace behind her as she lifts the dress to warm her buttocks. Three of the courtiers are smiling in presumed knowledge of what the queen is doing right in front the baroque crucifix hanging on the wall behind her. None of them, though, looks at the exposed part. The queen’s act is somewhere between the spontaneous desire to stay warm without regard for decorum and a self-conscious control of her surroundings in full knowledge of what impression her indifferent attitude creates. The year in which he painted the work Zahrtmann in an interview could tell that at her birth the queen was believed to be male and that later in life she had her lady-in-waiting Ebba Spare read dirty stories aloud for her just to watch her blush. On one occasion she appeared at the opera dressed in men’s clothes.77 In the painting her disengaged sexual provocation and “male” activities such as pipe smoking and contemplation of art make her a role model for the male invert at the turn of the century by transgressing the gender norms. As Jonathan Dollimore has suggested, the inversion of the existing norms can have a radical potential even as that means preserving them.78 Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini crystalizes several themes from Zahrtmann’s images of Leonora Christina, but a displacement has taken place. What was moralizing and constructive in the scenes with the Danish princess has in the image of the Swedish queen become a self-conscious play with norms for proper behavior and the transgression of these by virtue of her royal status. In this respect Queen Christina offers a parallel to the equally “aristocratic” Zahrtmann and his artistic license.

The relative obliviousness into which Zahrtmann’s later production fell after his death has been continued by Danish art museums. This expresses a resistance toward Zahrtmann’s self-conscious and ironic play with norms of respectability, sexuality, and gender. Once we take Zahrtmann’s humor serious his works will reveal themselves as subversive commentaries to bourgeois culture in turn-of-the-century Denmark.

(Translated by the author.)

Postscript 2019

Morten Steen Hansen, cand.phil., ph.d., Accademia di Danimarca, Rom

In the summer of 1993 I submitted my Honors Thesis on Kristian Zahrtmann at the University of Copenhagen. Selected parts of the text I turned into an article. For the current exhibition on Zahrtmann I decided not to revise it (apart from a few factual changes) because, reading it in retrospect, I find so many imperfections that I would likely end up writing a new article all together. This has not been feasible, nor would it be fair to a piece of work that I wrote as an undergraduate. When translating the text into English I did, however, cut some of the already lengthy notes. The methodological premise I still consider valid: That a historically relevant approach to Zahrtmann’s “decadent” paintings needs to be informed both by the artistic theory of the period and a Foucaultian history of sexuality that is based on the premise of sexuality as a historical construction.

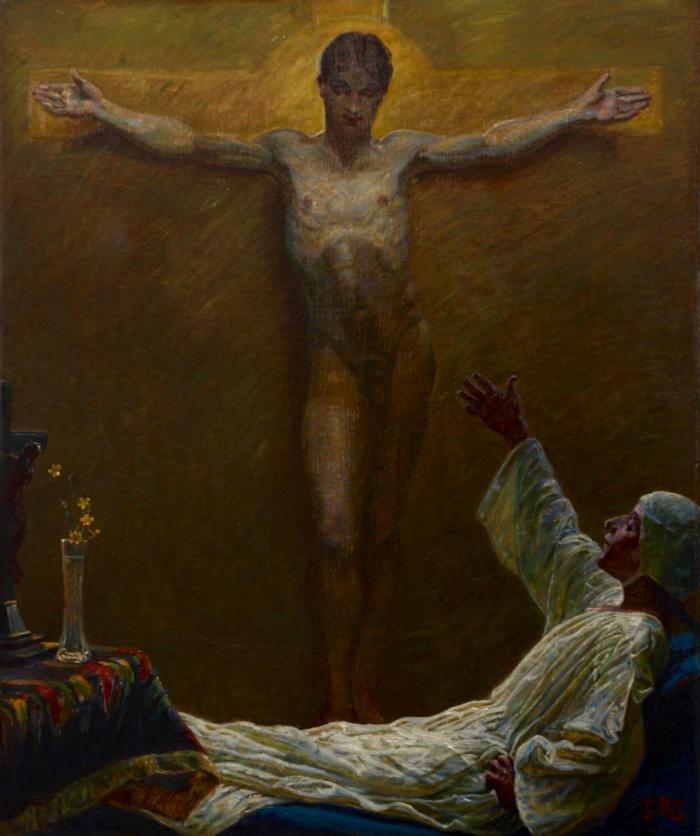

When writing about Zahrtmann in the early 1990s at a time when queer theory was coming into being I was struck by the extent to which the paintings of Leonora Christina, the most popular and well-publicized part of his oeuvre, continued to be taken at face value, their campiness and gender ambiguity going unnoticed. I was also struck by how few of Zahrtmann’s more outrageous paintings were in public collections, even though he by no means is underrepresented in Danish art museums. Since then Statens Museum for Kunst has acquired both Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini and the 1911 version of Socrates and Alcibiades, and Randers Museum of Art has added St. Catherine of Siena of 1914 to its collections [fig.19]. Hopefully, the present exhibition will lead to more works by Zahrtmann entering public collections. Below are a few additions to my previous analyses plus a proposed philosophical context for further inquiries into the artist’s works.

Regarding Zahrtmann’s male nudes it is worth noticing that his contemporaries did not automatically consider them inappropriate. The works that did make the critics uncomfortable implied the beholder directly in eroticizing the body. This is the case with the large Adam painting, where the snake becomes an extension of the beholder’s gaze and quasi-physical presence. Knowing that Zahrtmann later would paint In the Snake Pit of 1915 (DS 1135) [fig.20], where a nude man is violently attacked by snakes(!), it is difficult not to see a sadomasochistic subtext to his Prometheus, the iron chain touching his genitals. There is, however, nothing to indicate that the majority of his early audience saw anything provocative in the heroic, tragic figure, a reincarnation of classical traditions in the formal language of modern naturalism. That Zahrtmann was thinking of a “lovemaking of the gaze” when painting the Adam figure with the snake/beholder’s gaze/phallus entering from below is also suggested by the photograph he had taken of himself and the model for the painting inside his studio in 1914 [fig.21]. He is seated in the right foreground, turning his head inwards toward the model seen from behind, who bends forward in a display of his buttocks. The configuration of anal eroticism and sexual inversion is also brought into play in Zahrtmann’s androgynous Queen Christina in her exhibitionism and the pleasurable sensation she experiences from the heat.

In Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini the one character in the painting with full visual access to the Catholic convert’s exposure is the crucified Christ The semi-blasphemous wit direct attention to an important context for Zahrtmann’s art, the thought and atheism of Friedrich Nietzsche, introduced in Denmark by the literary critic Georg Brandes (1842-1927), whom Zahrtmann greatly admired. In November 1887 Brandes and Nietzsche began corresponding, which lasted until the outbreak of the philosopher’s mental illness little more than a year later. In 1888 Brandes for the first time lectured on Nietzsche in Copenhagen and in 1889 wrote An Essay on Aristocratic Radicalism, published 1914 in translation in London together with his other writings on the philosopher and their correspondence.

Nietzsche’s idea of a novel aristocracy of the spirit found favor with Brandes, and it could have fueled Zahrtmann’s snobbery, which at best puzzled his contemporaries. In this light the classism of his Italian scenes is revealing. As a teacher Zahrtmann’s famously insisted that the students be true to themselves without retort to convention, which finds a strong echo in Brandes’s writings on Nietzsche. In his art perhaps the most interesting expression of the German philosopher’s ideas comes across in the intensity of sensory experience, which, apart from the eroticism of the male nudes, above all is communicated in his colorism. At its very best Zahrtmann’s color is ecstatic, intoxicating, “Dionysian.” Rather than a sense of liberation, though, Zahrtmann’s art creates a sense of enclosure, his scenic spaces tending to be claustrophobically limiting rather than expansive. The effect is produced not only in his interiors but also in paintings of the outdoors. Interestingly, Zahrtmann’s heroine Leonora Christina wrote her autobiography while in prison. Such tensions in the art of the burgher/provocateur make Zahrtmann one of the strangest and most fascinating figures in turn-of-the-century art.