Summary

Narratives of growth and yield are pervasive when the history of Danish agriculture is written, and works of art are often used to illustrate the story. But what kind of world can art open up for us when it is not only seen to be illustrating a development, but looks back at us through the eyes of the cows? What story do the artists let the cows tell? This article looks at works purchased for SMK – National Gallery of Denmark in the period 1880 to 1900, a time when the industrialisation of Danish agriculture took off in earnest. The article investigates how the artworks reflect the overall change in our relationship with the world which took place when the cow became a production animal instead of an ally.

Articles

The cow is one of our oldest allies in the landscape.1 It has followed us across great distances and we have lived alongside it in a close mutual relationship, tending to it as herders while it in i has given us its milk, its meat, its labour and its manure. In Denmark, cattle have very much shaped the landscape. For centuries, they have ensured that the grasslands did not become forests, and the monocultures that have increasingly spread across the Danish landscape largely serve to provide fodder for livestock. Without cattle, the landscape would have looked completely different.

Cattle have played an important role in landscape painting through the years, and this is also true for the two decades from 1880 to 1900, a time described as the point when intensive agriculture with large livestock holdings, imported fodder and intensive crop farming had its major breakthrough in Denmark.2 In several respects, the type of agriculture we see in Denmark today represents a further development of this approach.3 Turning to the realm of art museums, landscape paintings from this period can shed light on that development and how it is connected to our experience of the world. However, this requires us to see landscape painting in a new way. Thus far, discussions of agricultural subject matter from the period have tended to focus on humankind’s struggle for existence or on stylistic developments impelled by influence from abroad, especially France.4

The works acquired for SMK during that period display far greater breadth than that, however. These depictions of cattle can give us an important indication of the changes in our outlook on the world; changes that took place when the development of industrialised agriculture gained momentum. The works offer an opportunity to explore what was at stake at a time when a specialised and professionalised approach to agriculture greatly changed our relationship to our surroundings and thus to the landscape. The artists of the time addressed this theme directly. This holds true when artists, through the representation of individual animals, offer us a point of entry for experiencing the landscape and its life forms – and also when, through colours and shapes, they let us uphold the illusion that no one in the landscape is looking back at us.

In a time of climate and biodiversity crises when very few of us actively cultivate the land or interact with domestic animals, the question of how we meet this part of our history in museums matters. Inspired by the way in which Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, professor at the History of Consciousness Department at UC Santa Cruz, engages with the notion of our environment as a multispecies community, I use cattle to pave the way for a new understanding of landscape painting, one which can reflect back on our understanding of the times in which we live.

At present, the UN, acting via The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), urges us to change the way we farm.5 As regards Danish agriculture, the warnings particularly concern the problematic aspects of our large number of domestic animals and the extensive areas used for growing animal feed in the form of monocultures, an issue also pointed out by organisations such as The Danish Society for Nature Conservation.6 The Danish agricultural landscape has become political. This makes it all the more interesting to examine the role played by art in the period 1880 to 1900. When this type of agriculture became firmly established, artists not only supported the new order but also, in an activist-like manner, showed us what was going on.

Between constructed and living landscapes

Informed by the theoretical approaches of ecofeminism, New Materialism and posthumanism, Maria Puig de la Bellacasa points out that this outside world consists of ‘more-than-human worlds’. Here man is only one agent (or agency) among the many organisms, objects and physical forces which together create worlds. Every action and thought that takes place here is situated in a multiplicity of relationships and interactions. Here it is impossible to distinguish between man and nature and between the living and non-living. It is not only us and the animals who act; so too do plants and soil, and our agency and that of others cannot be seen or thought of independently of each other.7

This awareness of an outside world of agency and complexity, a world created through the interaction of many different forms of life and materialities, has only to a limited extent been discussed in relation to landscape painting. Landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn, however, makes clear that the etymology of the term ‘landscape’ points to a state of mutual creation: ‘people shape the land, and the land shapes people’,8 and art history has applied a particular focus on how humans create and manipulate the landscape. ‘A “landscape”, cultivated or wild, is already artifice’ is the opening sentence of art historian Malcolm Andrews’s Landscape into Western Art, and as art historian Mark Cheetham puts it: ‘For humans, landscape is always cultural, especially when that implies that the practice of “landscaping” in its broadest sense articulates border lines with what is not human and between human communities’.9 His book Landscape into Eco Art very precisely maps the position and impact that landscape painting has had for those artists who have since worked with nature as a focal point. Here it is clear that landscape painting is viewed with great scepticism as an instrument for the colonial and profit-oriented gaze instrumental in creating both global injustice and climate and biodiversity crises.10 At the same time, it has been pointed out – for example by historian W.J.T. Mitchell in the second edition of Landscape and Power – that the power that can be expressed through a landscape is diffuse and weaker than the power exercised by armies, governments and corporations. According to Mitchell, this diffuseness rests on the fact that a landscape invites you to view the totality rather than individual elements. To see the landscape is therefore to look for nothing or to see yourself seeing.11 However, the power of landscape painting should be reassessed. How we see the world around us affects how we act and respond to the climate and biodiversity crises, and looking at the landscape just to see oneself is problematic in a time that, according to the UN, demands urgent action.

It is thus crucial to look critically at how landscape painting has helped to support a utilitarian, profit-oriented view of our world around us, encouraging a myopia that – as Mitchell points out – puts emphasis on the act of seeing and on establishing an overview rather than on the living and complex world of which we are part. At the same time, it is also crucial to highlight the many artists who do not fit into this landscape concept and who emphasise the living and creative landscape where humankind is just one among many agents. The notion of a living landscape is present in many of the artists who worked in the nineteenth century. As the writer and thinker Amitav Ghosh puts it, the idea of landscapes being alive is not a present-day invention. Rather, according to Ghosh, the notion of the ‘artificial’ and non-living landscape as a phenomenon can be localised to a period of only a few hundred years within a particular, elitist part of Western thinking.12 Several others have pointed this out. For example, the philosopher Lorraine Code’s Ecological Thinking posits a particularly science-oriented understanding of nature in the Age of Enlightenment and looks at how it has contributed to creating the environmental crises that characterise our time.13 Bridging the Enlightenment and our highly industrialised age, the nineteenth century is interesting in terms of examining how the two notions of the outside world as living and non-living clash and fray.

Looking into the tradition of landscape painting for the negotiation of such a dialectic, the cow can serve as a landmark by which to navigate. Testing the distributed agency of landscape through the cow is interesting because it can be easier to empathise with a farm animal than with wild animals or plants whose relationship to humans does not have the same intensity. With its millennia-long history of association with man and given the ways in which it interacts in multi-faceted ways with its surroundings via grazing, fertilising, trampling and traction, the cow makes for an obvious candidate for study. It offers an empathetic point of entry into the landscape depicted – although the question of empathy between cattle as production animals and humankind pose thorny questions of what empathy and care really are.14

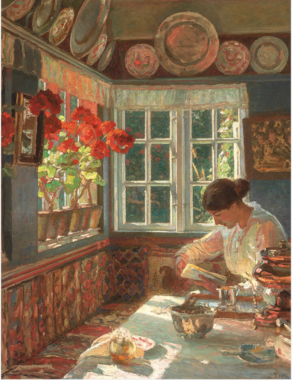

Cattle appear in many different ways in Danish art between 1880 and 1900. This applies, for example, to in Niels Skovgaard’s painting Willows beside a Meadow near Nysø Manor, South Zealand [Fig. 1], where the cow – despite the title’s focus on the willow trees – forms an important point of entry to the peaceful and lush nature depicted by the artist. Like the human figure with its back turned to the viewer, a typical trope of the time when representing humans indoors, the cow helps the viewer’s gaze into the picture.

The reddish-brown cow seems immersed in a landscape full of agents. It swishes its tail, perhaps to keep insects at bay, and is seen through the gently swaying blades of grass in the foreground. In the right-hand corner are docks which, like the row of willows, are reproduced in great detail with a keen eye for the glossy, almost glistening upper sides of the leaves. A stork struts in the background to the right. The cow is not only an observer of these many forms of life but also a discreet agent when it bends and presses down vegetation with its body, turning the plants that break into food for new ones. To this we may add the fact that it is presumably chewing the cud after stimulating grass growth by biting down the plants, and that it might soon be fertilising its little green corner of the world. The multiple ways in which it interacts with its surroundings stimulate a richness that we would today treasure as biodiversity, and Skovgaard implicitly revolves around them in his picture. However, certain aspects are absent: there are no other cows nor any direct human interaction. The cow’s halter, however, shows that it is tethered, and had it lived a life without humans, its physiognomy would have looked quite different, just as it would hardly have been alone without its flock.

The question of looking at living landscapes with many agents is not necessarily about setting the animal free from its relationship with humans, but rather about seeing and treating the cow as part of a living world. This outlook on the world is different from the one linked to production-focused agriculture.

A landscape painting comes into being through co-creation. Real plants and animals have not only informed, but related to the artist and registered his presence. As anthropologist Eduardo Kohn has argued on the basis of Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotic theory, the act of reading and exchanging signs is not the exclusive purview of humans.15 Just as the portrait painter uses their work process to get under the skin of their sitter and reproduce their vulnerability, pride or other psychological traits, the landscape painter can spend hours in front of plants, animals or geological formations to immerse themselves in the life unfolding before them and transfer their observations to a flat surface. Another equally radical extreme also exists: pigments can be applied to a painting support in a process that focuses solely on colour, brush and picture plane without any reference to a concrete reality. Still, even those artists who evoke landscapes with just a few lines have at some point let their gaze rest on one. Something has registered a presence at some previous point in time, even if the painter chose to shut most of it out. Most painters operate in the wide range between the two extremes. The issue is thus not a question of accurate verisimilitude, but of choosing to represent the living.

The American portrait painter Alice Neel aptly describes the empathy-oriented extreme when she explains her own process with sitters: ‘I get so identified when I paint them, when they go home I feel frightful. I have no self – I’ve gone into this other person […] It is my way of overcoming the alienation. It’s my ticket to reality’. And: ‘they unconsciously assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their character and social standing – what the world had done to them and their retaliation’.16

Neel becomes so deeply involved in how each individual relates to the world that she feels empty when her subject matter disappears. She reproduces a life world of which she herself is part, focusing on the mutual exchanges between the living. If we transfer this to Skovgaard’s picture, we see how Skovgaard empathises with the cow and the landscape, recording what the world has done to the cow, the stork and the willows – and what the cow, the stork and the willows have done to the world. They – or in a broader sense the world – can look back at us through the picture, and this opportunity to form a link between us and the world is a particularly interesting subject for study in light of the developments seen in rural Denmark back when Skovgaard painted his picture. In this context, empathy constitutes a way of trying to open up and share the world of others, and in that resides an ethic that is crucial in a time of climate and biodiversity crises.

Milk yield and productionism

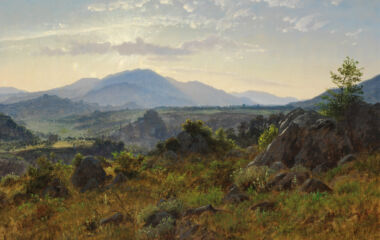

According to Det danske landbrugs historie (The History of Danish Agriculture), in 1880 Danish agriculture was poised on the verge of ‘the decade in which intensive agriculture had its breakthrough’, ushering in a 65% increase in the Danish livestock population up to 1914.17 The book puts forward figures and speaks about the ‘increase in animal production’, stating that ‘the milk yield per cow increased strongly, and the fattened animals were ready for slaughter at ever-greater speed’.18 The rhetoric reflects an interest in numbers over life that is also evident in volume 2 of Landmandsbogen (The Farmer’s Handbook) from 1895, which very tellingly opens with a vignette of symmetrically arranged skulls that is repeated with variations throughout the book [Fig. 2]. In the preface, Harald Goldschmidt, docent in animal husbandry at the Royal Danish Veterinary and Agricultural College, specifically points out that the purpose of the book is ‘to make animal husbandry as profitable as possible’.19

Such a focus on efficiency that directly impacts the bottom line is the epitome of how, according to Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, a particular ‘productionist’ mode of thinking has evolved in agriculture. A drive to create ever-increasing dividends in which a one-sided focus on yield colonises all other relationships and values. Farmers have always focused on profit, but not necessarily at the expense of their relationship with other forms of life and future possibilities for cultivation.20 In this kind of thinking, the main focus is on the product rather than the process. Looking specifically at cattle, this means that the focus is not on how many cows a given area of grassland can support. Rather, a target is set for how much milk is desired, and then feed is purchased and produced to match this. Similarly, cows are specifically bred to give more milk. No account is taken of the fact that resources such as feed are limited in terms of time and space, and that even within the context of globalised agriculture one must at some point consider what is available and how quickly resources are regenerated.21 As climate scientists such as Will Steffen and Katherine Richardson have pointed out, failure to consider this aspect involves the risk of exceeding the boundaries of what the planet can sustain. Thus, they emphasise that any production must be sustainable.22

Productionist thinking does not take this into account – nor does it consider all the other ways in which cows create worlds around them: how the life and death of other species is conditioned by the cow’s grazing, trampling , manure, heat, etc., and how the cow interacts with other life forms.23 The cow is seen purely as an individual unit of production, and the farm where it lives is not a diverse world that supports a family and a local community, but an industrial enterprise and a workplace focused on a limited range of products.

This productionist thinking, which as far as cows are concerned has a one-sided focus on milk, is clearly evident in contemporary and later descriptions of this development in Danish agriculture. In the many pages of The Farmer’s Handbook, farmers could find inspiration on subjects such as what particularly optimised cows would be able to yield and what kind of input they required. The question is whether they could also find inspiration at SMK – the national gallery of Denmark? Among the 200 paintings dated and acquired for the collection between 1880 and 1900, we find a total of forty-two where the cow, bull, steer or calf is a focal point or has left an imprint on the depicted landscape.24 Here we find paintings where the animal is painted in great detail and with obvious agency, such as in Willows beside a Meadow near Nysø Manor, South Zealand by Niels Skovgaard, A Runaway Cow by Michael Therkildsen and A Road in Jægersborg Deer Park, North of Copenhagen, Autumn by Theodor Philipsen. There are also works by Otto Bache and N.P. Mols such as Driving Cows out of the Cowhouse and Beet Lifting, where the animals look out at us and invite us into their reality, and there are landscapes which the cows have helped to shape, yet where they seem absent as creatures with agency. For example, this holds true of Julius Paulsen’s Landscape near Kolding, Jutland, at Sunset. All these works were acquired during the 1880s and 1890s, the time when our shared notions of what a museum should be took shape, and they offer an impression of what were considered desirable representations of the Danish agricultural landscape at the time. Most were bought while the major landowner Otto Rosenørn-Lehn was director of the museum, acquiring works in collaboration with various co-purchasers – including the prominent art historian Julius Lange.25 Rosenørn-Lehn greatly influenced how the industrialisation of the Danish landscape was perceived by the segment of the population who visited the museum.

A Runaway Cow

Under a sky tinted in shades of grey and white, a farmer strides determinedly ahead, a tether tucked behind his back while his right hand is extended in a gesture of enticement. A cow watches him warily, ready to either let herself be tethered or run away. In the meadow, daisies bloom among clover, grass and other herbs. The artist and farmer’s son Michael Therkildsen captured this scene in the painting A Runaway Cow [Fig. 3] from 1890, and the work was purchased for the national gallery of Denmark the following year. In addition to a detailed depiction of the cow which has escaped its tether, the picture also incorporates fleeting yet precise representations of the many plant species that grow in the meadow. One certainly understands the cow’s choice of setting, and Therkildsen devotes his full focus on the relationship between cow and farmer, assigning agency and initiative to both. Here we are far removed from rhetoric on milk yield: a state of balance is maintained in the picture, between sky and meadow and between cow and farmer. There is communication here, but also scepticism, and one sense that the cow will only be caught if she chooses to surrender.

Tethering your cow in a particular piece of land you wanted to have grazed and fertilised was a widespread practice at the time. The daily chores involved moving, watering and milking as needed. Often, a boy was tasked with moving it and a girl with milking it, and as a farmer’s son Therkildsen must have been familiar with such work.26 The Farmer’s Handbook describes tethering as more economical than leaving the cows free to roam, as this involves less trampling and fewer plants being rejected. From the point of view of health care, however, free-range farming is preferred as it gives the animals the opportunity to move and enables the cow to find shelter and choose the plants it likes the best. A third alternative, feeding the cattle in a barn for a greater or lesser part of the year, is also described in the handbook, specifying how various skin and gas problems derived from this practice can be overcome.27

It is likely that Therkildsen has here depicted the breed known as Jysk Kvæg (Jutland Cattle), which was a dominant breed at this time in Jutland despite many attempts to have it replaced or ‘refined’.28 Being described in The Farmer’s Handbook as a pleasant, undemanding and hardy breed with juicy meat and a reasonably good, consistent milk yield, this animal reflects a type of agriculture which focuses on self-sufficiency and a barter economy.29 In such contexts the cow’s amiability and hardiness are as important as its milk and meat, and being economical in terms of its demand for feed was crucial. Therkildsen thus shows us a way of keeping cows that was prevalent until around 1880, yet which was changing at the time as the sale of milk was becoming increasingly central to financial viability, including for smaller farms. Gradually, not only most of the grain and turnip production from the fields, but also substantial imports of feedstuffs would be processed through livestock.30 However, Therkildsen’s interest does not centre on this development. He depicts a form of operation common at the time, focusing on the cow’s agency and interaction with the farmer. His narrative style differs greatly from the agricultural history being written by the authorities. Therkildsen’s version veers much closer to the many personal accounts of caring for cows, such as Kristian Bruun’s account of letting a farm’s few cows ‘pass by tempting fields of clover’ on the way to the place where they were to be tethered.31

A cow is also loose in Theodor Philipsen’s painting A Road in Jægersborg Deer Park, North of Copenhagen, Autumn [Fig. 4], and its agency is important to the narrative of the monumental painting. While the cow is not mentioned in the title, the picture’s point of view belongs to it. We see the forest where the leaves are turning, individual streaks of sunlight enhancing the play of colours. We join the cow in looking towards three other cows among the trees, their red coats matching the reddish-golden autumn leaves. Like a wanderer, the black pied cow is making its leisurely way into the picture, its head raised as it picks up the eddies of the wind and the humidity in the air. Using rapidly applied, impasto brushstrokes, the painting technique emphasises atmosphere and a sense of capturing something ephemeral.

Philipsen was trained in agriculture. For two and a half years he was apprenticed at his uncle’s farm Højagergaard near Slangerup, and he was subsequently a tenant farmer at Hillerødsholm for two years. Both were large farms, and Hillerødsholm was a ‘hovedgård’ – a major estate – with a royal stud farm and a dairy. Thus, Philipsen would have been familiar with large- scale animal husbandry, and in his capacity as an artist he visited numerous manors and major estates around Denmark, aided by his uncle’s extensive network of connections.32 The fact that he selected the Jægersborg Deer Park as the backdrop for these cows raises the question of who sent these cows to the forest in autumn time. The area was originally the property of the crown, but in 1669–70 the village of Stokkerup was demolished, the farmers relocated, and the forest fenced in, becoming entirely dedicated to the king’s deer hunting. Having said that, public access to the area was introduced in 1756, and markets and various types of entertainment arose in the area.33

Given the nature of the Deer Park, the cow comes across as a foreign element or pure invention according to Philipsen researcher Finn Terman Frederiksen.34 Perhaps, however, it can be seen as a kind of ghost. Its presence points towards a form of agriculture practiced before the Danish agrarian reforms at the end of the eighteenth century, one where town cowherds would take the cattle to pasture or to the forest until the 1805 Forest Act introduced the forest reserve regulations which stated that the woods had to be kept free from livestock.35 Might Stokkerup’s cows be haunting these trees? Perhaps the painting is Philipsen’s reply and comment on a strong tradition within agriculture that provided subject matter for iconic works by Danish Golden Age artists such as Johan Thomas Lundbye, a painter to whom Philipsen relates directly in other works.36 Perhaps the painting can be seen as a humorous retort to the changes brought about by new agricultural policies where the commons became sites devoted to pleasure rather than utility. By virtue of its ambiguity, the painting invites active engagement and empathy from audiences who, at the museum or exhibition, bring to bear their own experiences from the Deer Park.

When production animals return our gaze

The narrative in Otto Bache’s Driving Cows out of the Cowhouse [Fig. 5] is rather more straightforward. A man walks at the front and another raises a stick at the back while a motley crowd of at least twenty-seven cows and a bull are driven to the left and into the scene. Some are hesitant, others cavorting. The sun is rising, shining palely through the haze, and according to the second part of the original title, it is a ‘Late October Morning’. But what kind of cattle husbandry is Bache depicting here, and how does it connect with his choice of expressing himself on a vast canvas measuring more than 2 x 3 metres? The painting is signed 1885, the same year it was bought by the national gallery of Denmark, whose former rooms at Christiansborg Palace had perished in a fire the year before. Bache took a gamble that paid off: the large work found a buyer.37

The scale of the painting is not alone in being ambitious; so too is the size of the herd of cows. This is no ordinary farm: in the 1880s, herd boys were generally responsible for six to eight cows.38 Clearly we are dealing here with one of the larger farms that contributed to driving the development towards cows bred specifically for high-fat milk.39 Such farms often had small-scale dairies of their own. This development was not conditioned by what happened in Denmark. According to Det danske landbrugs historie (The History of Danish Agriculture), the way cattle was kept was affected by the fact that grain prices dropped from the end of the 1870s when grain products from fields established on the prairies of North America flooded the Danish market, helped along by easy and cheap transport via railways and steamships. As the price of animal products did not fall correspondingly, Denmark chose to buy up foreign grain for feed and supplement it with palm and coconut cakes as well as cottonseed cakes in order to boost the fat content of the milk and thus the quality of the butter.40 The farms now became businesses with expenses for purchased feed materials that might eat up 30–40% of the income received from the sale of the produce.41

Bache’s cows are very likely to have been a result of this global development, which increased the number of cattle in Denmark while at the same time creating a new type of cattle and fostering a different view of them. Breeding was now done specifically with the aim of creating specialised dairy breeds. The cows depicted here have just been milked, their udders hanging limply. However, they are not producing milk for the household and are not handled individually, but as a herd. The roughness inherent in the raised stick shows us how this everyday action is carried out through force rather than cooperation [Fig. 6]. A shift is taking place as regards the empathetic view of the cow: one product is colonising other relationships and values, as Bellacasa would put it.42

Bache has chosen to focus on this precise theme. Several fearful bovine eyes look out at him, not least those of the cow with the white head and brown ears. Its body has been painted in great detail, as if the painter were portraying a peer. The animal turns towards him, but it also seems as if – with open ears, eyes, mouth and nostrils – it takes in the rest of the world. The empathetic Alice Neel might say that it reflects what the world has done to it. According to art historian Sigurd Müller, Bache met ‘each animal as an individual that demanded being recognised as an independent character, and he always succeeds in getting the viewer to recognise this demand’.43

With his monumental depiction of cows, Bache posits himself in the middle of the general development towards larger and more specialised farms that took place when the drop in grain prices brought about a crisis. He also raises questions. Why this crisis and this response to it? One might continue this train of thought: Why did the farms become so dependent on the sale of products – couldn’t they just be self-sufficient? Did farmers need to make payments on loans taken out when brothers and sisters had to be bought out when the farm changed hands from one generation to the next, or did they need to pay high taxes to the very state that bought Bache’s painting and received vast revenues from agriculture around this time? Did the farms opt to become industrialised in order to assert themselves and gain political influence, or were the farmers simply concerned with progress for the sake of progress?44 These are questions that are only rarely touched on when agricultural history is written, unless individual farms are addressed. Yet they are interesting questions, and artists can contribute points based on visits to specific individual farms. Manors and smaller farms obviously faced different conditions, yet shared similar dynamics. Bache, who had grown up in Copenhagen in modest circumstances, mainly visited the big farms,45 but by showing the darker aspects of large-scale farming and sharing his observations on the loss of empathy in dealing with the animals, he outlines a dilemma that applied to small and large farms alike.

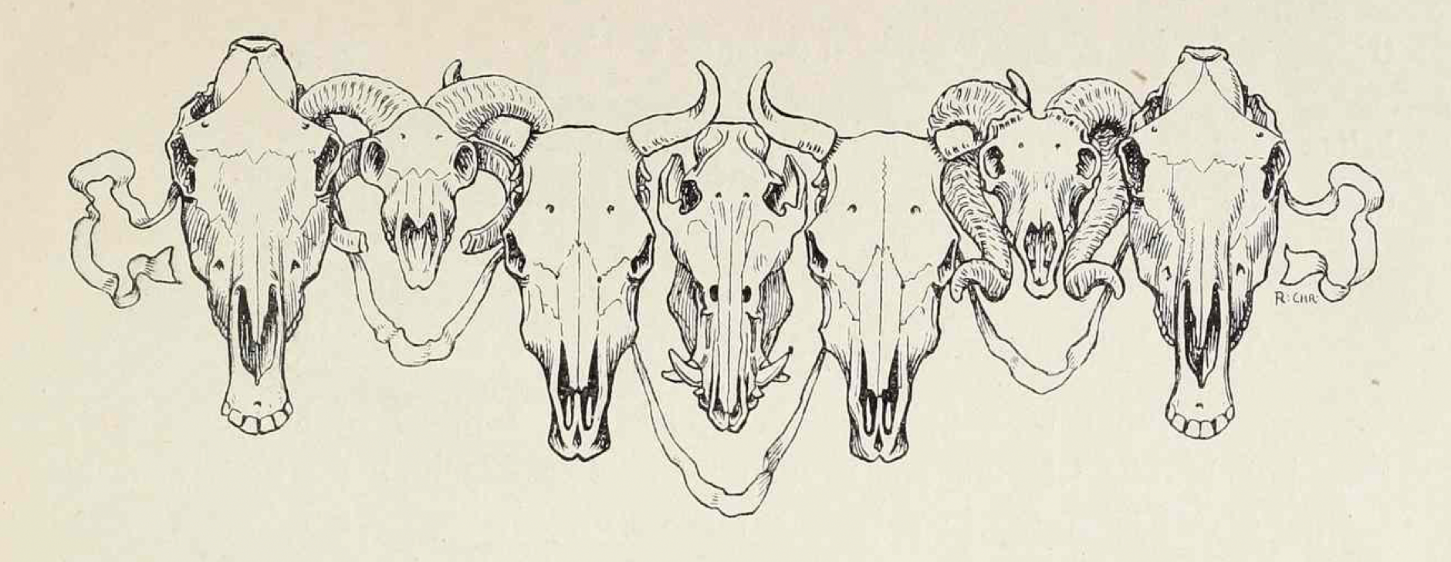

Niels Pedersen Mols was a smallholder’s son from Grumstrup outside Aarhus, and as such had close ties to agriculture. He depicts another side of the reality faced by production animals in Beet Lifting from 1886 [Fig. 7], which became his breakthrough picture. Here we find an atmosphere of equality and cooperation between the two bullocks and the man who picks up the fodder beets while a little boy looks on with a whip in his hand. The boy and man are both faceless, a stark contrast to the central focal point of the picture: the bullock on the left, placed in the centre of the picture, looking out towards the viewer. Unlike the other bullock it has raised its head from the fodder beet tops it is munching.

The two crucial elements that Mols brings together in this picture are the bullocks and the fodder beets, each of which has its own story. The cultivation of fodder beets used for feed grew in scope in Denmark in the 1880s, but it was a labour-intensive crop: in addition to harvesting, it required ploughing, sowing, thinning and weeding. However, fodder beets provided more than twice the feed energy compared to grain, and with fodder beets you could feed the cattle from the beginning of October until well into May.46 According to Landmandsbogen, fodder beets were preferable to natural pastures: under normal conditions grass could only briefly match the benefits of an abundant feed of fodder beets in the ‘fattening of cattle’.47 In Mols’s picture, the fodder beets are plentiful, big and splendid, and the little boy is well dressed.

While the fodder beets point towards recent developments in agriculture, the bullocks reflect a centuries-old practice in West Jutland. Mols painted the scene at Nissum Fjord, which is well situated for the West Jutland road that had been used for centuries to drive cattle that was to be shipped from Esbjerg to England or traded in cities such as Hamburg. Such trade made West Jutland a centre of commerce rather than the hinterland it has sometimes been perceived as.48 The two well-nourished bullocks served a dual function as draft animals and marketable beef cattle. Their raw strength is offset by the gentle expression that bullocks often have, being castrated bulls, and Mols has captured this precisely. The point is further emphasised by the bullock’s gaze being placed in the centre of the picture. In 1908, the animals’ expression prompted one reviewer to describe the bullocks as ‘teddy bears’ in Illustreret Tidende (Illustrated News), while in 1901–7 the art historian Francis Beckett stated, rather condescendingly, how Mols has ‘preserved a childlike love for the animals and a childlike understanding of them’. Even so, Beckett also believed that ‘the famous bullock head in Beet Lifting is distinguished not only by the fineness of the form and drawing, but also by the irresistibly kind, friendly look in the eyes, and this sense of doughty kindness communicates itself to the viewer’.49 Although Beckett thus partially offsets the condescension inherent in his analysis of the artist’s childlike qualities, it is interesting to note that the critic does not notice the aspects of contemporary relevance and enterprise, nor does he pay any heed to the historically important trade in bullocks that had made West Jutland an international centre. The two monumental works by Bache and Mols home in on the general development towards keeping larger herds of cattle, and Mols points to the changes this brought about in the landscape due to the new methods of feeding. Cattle were streamlined as part of an increasingly industrialised approach to agriculture, but cows and bullocks look back at us, and the relationship between humans and cattle is central to both works.

Diffuse landscapes of production

The rise in Danish cattle population is not visible in Julius Paulsen’s Landscape near Kolding, Jutland, at Sunset from 1896 [Fig. 8]. Paulsen paints using his typical, slightly blurred brushstrokes, and spotting the cows is difficult. There is just one or two to be seen, their presence hinted at by indistinct brown smudges close to the first hedge [Fig. 9]. Perhaps they are not even there at all. Even so, cattle – being central agents in Danish agriculture – helped create this landscape: over centuries, their manure made the fields fertile. Also, by prompting the cultivation of grain, turnips and other crops used to feed animals in their barns, the cows contributed to creating the monochrome, uniform surfaces emphasised by Paulsen.

When considering the developments from 1860 until 1912, one finds that despite the conversion to animal husbandry and the substantial imports of grain, farmers did not grow any less grain in Denmark. The share of cultivated area used for monocultures remained stable.50 However, Paulsen is vague on this issue, perhaps even disinterested. He shows us hazy shimmers of green and gold rather than plants, and it is difficult to determine at what time of year he ventured into this landscape. Even the foreground is diffuse and lifeless. Indeed, the key aspect of this painting may be the fact that no one looks back at us. Neither humans, plants nor animals. Even the air seems empty. Paulsen is utterly alone with his mood and atmosphere. He may feel something but is alone in feeling it. He thus works with the diffuse and subtle power that Mitchell identifies when describing what landscape painting can and cannot do.

Interestingly, the only figure that really stands out in Paulsen’s landscape is the mill. We even find an extra one on the horizon, placed exactly in the centre axis of the image. Mills were agriculture’s most conspicuous industrial buildings at the time. The erection of mills, new barns and stables were a sure sign of the industrialisation of agriculture. Between 1840 and 1897, the number of watermills and windmills in Denmark grew from 1700 to 2800.51 By showing us the mill and the clearly demarcated fields, Paulsen presents us with a landscape where man has left clear traces. Through his diffuse gaze, he overlooks the potential presence of other actors in order to focus on his own agency – and that of his own species.

Art as a laboratory for the future

If we look closely at the landscape paintings from 1880–1900, it is clear that the artists present us with different takes on living and not-so-living landscapes. As curators at the museums, we have a responsibility to show the breadth and scope of such landscapes when we arrange exhibitions and hangs, and to show how the relationships with the world presented by the artists are pertinent to our time. The artists display great variation in terms of how they viewed their surroundings: some ignored or overlooked different forms of life and agency, others emphasised them. In Skovgaard’s painting we see the interaction of many forms of life and agency: here the cow becomes a point of entry for immersing oneself in a landscape full of life. We see a cow deprived of its herd and its direct relationship with humans, but at the same time it orients itself – and thus also us as viewers – towards a landscape full of life. Skovgaard’s work gives us an important angle of approach in our efforts to understand our relationship with the cow and the landscape. The cow is not only there for us: we are in this together, and the interaction is not necessarily free from requirements and the need for adaptation from both sides.

Therkildsen tackles some of the same issues with his cow on the loose, but by way of his depiction of the cow’s owner, emphasis is placed on the relationship between man and cow, despite the richness of different species in the meadow. Turning to Philipsen, we find ourselves in a separate league. Despite the realism of the light falling upon the autumn forest and the artist’s personal background as a tenant of a farm, the cows seem strangely out of place. At a time when cattle were increasingly being moved inside into barns, his picture moves them to the forest to act as stand-ins for us. At a time when these animals were increasingly perceived as soulless cogs in an industry, they are imbued with spirit and soul here as wanderers in the wood. However, the idealisation seems so caricatured that they should presumably be perceived as a parody of the anthropomorphising of animals.

With Bache, we come face to face with stark reality. The cows no longer walk by themselves but must be driven along with raised sticks. They have been milked and fed, and now it is time for them to roam the pastures until the next milking and feeding. The large herd foreshadows the kind of large-scale operation so characteristic of the industrialised agriculture of our time. Here, the sheer number of cows erodes the observation of and empathy for the needs of the individual cow and its interaction with other forms of life. However, Bache does not show us a herd of identical individuals, but a motley crowd that responds differently to human agency. Several of them even turn their gaze towards yet another human being, the artist.

Mols shows us a landscape that has no cows but does have fodder beets and two bullocks whose powers of traction and muscle mass show us another aspect of how cattle was seen at the time. Like the calories from the butter which formed the focus of agricultural production at the time, traction is a form of fuel. As was the case in Bache’s work, the gaze directed at us by Mols’s bullock defies and punctures the de-souling inherent in such a way of viewing the world. And this is precisely what it is all about: orientation. The artists I have been studying address how we orient ourselves to and in the world. This also holds true of Julius Paulsen even if he does not use the cows as a gateway to empathy and orientation. Here the focus is neither on the cow nor on the other life forms found in the landscape, but on the human way of looking at it. Perhaps the lack of attention – so typical of the tradition continued by Paulsen – to the life around us is related to industrialisation’s focus on the product and the de-souling of the individual animal and its complex surroundings.

Risking oversimplification, one might suggest that the development seen in Danish agriculture in the 1880s and 1890s has certain parallels with the crisis in our relationship with the outside world we are all experiencing right now, manifesting itself in global climate and biodiversity crises. Even if such contentions are a stretch, it is important to examine the relationship between them: these crises concern not only the world around us, but also our imagination and ability to orientate ourselves. If we are to work actively with our imagination and our ability to genuinely see the many forms of life that create and make up the world around us, the depictions of cattle created during the two decades when the de-souling process took off in earnest can be part of an experiment – of a laboratory. In it, we can examine how we lost our bearings and the ability to see beyond our own agency and point of view.

The landscapes with cows show how the artists of the 1880s and 1890s reflected on the developments taking place in their own day. Their works can be viewed in light of the shifts occurring in the general understanding of the world at that particular time, and we may ask what would have happened if we had been able to let the cow remain loose, coexisting more respectfully with it as a living being that shares its resources with us rather than as a resource that simply needs to be provided with other resources in the form of food? Would we then have had more points of entry for looking at the life around us, more than the one offered by the blurred landscapes created by Julius Paulsen and so many others, landscapes in which we mostly just see ourselves seeing?

In our own present day, the focus is on the future rather than the past. The picture of the future outlined by the UN panel on climate change shapes the choices being made right now in terms of how we act in our environment. However, we must find not only new ways of acting, but also new ways of orienting ourselves in the world. The works addressed here can be curated on the basis of this very need. We can relate to the patterns of agency presented by the artists in a troubled territory of tethered cows and cows that are being driven yet look back at us. We are not presented with pastoral landscapes without Philipsen’s wryly ironic bite. Apart from Paulsen’s painting, which constitutes the only exception, the works of art have us stay within a problematic field that calls for us to orient ourselves and take a stand. In Paulsen’s piece the cow is just an ambiguous blob, but in the other works the animals’ poses and gazes give us the opportunity to assess what the world does to them and what they do to the world. Thus we are trained, as in the case of Alice Neel’s portraits, in exercising and honing our empathy.

According to the feminist art historian Maura Reilly, who is interested in how we can curate in activist ways, we need to count as we move through our art museums.52 We must ensure that our collections offer broad representation of female and male artists, of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Perhaps we should also begin counting cows and pay close attention to how cows and their landscapes are represented? We must ensure that we show landscapes where the artists let many forms of life come to the fore and have a voice, as well as works where we can, through the presentation and discussion of the art, ask how the production landscape is presented aesthetically and what that does to us. In an age of climate change and biodiversity crises where our relationship with the world around us must be reassessed, it is important to understand this part of our history. We need emotional renderings of the life forms with which we co-create the world, the ones with whom we entered into a renewed interaction when new developments took off. And we also need to look at the way we have created blurred landscapes out of the production landscapes with which we have surrounded ourselves. Many museum collections contain a wealth of positions that we can curate, and not least stories that we can tell, to open our imagination and point it towards a new reality.