Summary

This contribution examines Palestinian-Danish artist duo Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind’s exhibition Tomorrow’s Ghosts at Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg (30 March – 13 August 2023). It considers the two video works making up the exhibition, As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night (2022) and In Vitro (2019), as well as the installation project Archaeology in Absentia (2016–17). The exhibition review traces how haunting (Gordon, Ball, Derrida, Auchter, Fisher) operates in all three works and establishes it as an aspect of the past as well as of the future. The distinct spectral qualities that Sansour and Lind employ in their work highlight the ongoing Palestinian predicament and the ever-bleaker prospects of achieving a sovereign Palestinian nation state. At the same time, Tomorrow’s Ghosts challenges and reformulates conceptions of time, space and identity. By blending real and speculative geographies, mixing archival footage with science fiction, and collapsing past, present and future, the artists defy the continuous toponymicide (erasure of place) and memoricide (erasure of memory) that are the result of the lengthy Israeli occupation of Palestine (Masalha, Abu Lughod, Rachidi, Jayyusi). Tomorrow’s Ghosts gives ghosts a home and a voice, as well as a time and a place. Tomorrows, then, are not only located in the future, but are equally scripted in the past. Ghosts signify loss in this exhibition but are also the stubborn residue of resilience and hope.

Articles

Introduction: Ghosts and Haunting in Palestine

‘Ghosts,’ Avery Gordon famously noted, channelling Black American writer Zora Neale Hurston, ‘hate new things’.1This is ‘because ghosts are characteristically attached to the events, things, and places that produced them in the first place; by nature they are haunting reminders of lingering trouble’.2 Gordon elaborates further that ghosts’ aversion to the new is coupled to their haunting power: the more the events, things and places they are connected to disappear, the more difficult it becomes for the ghosts in question to haunt them.3 Ghosts, then, are place-bound; driven by the impulse to return to the site of trouble. But ghosts are also very much time-bound, flitting in from the past and the future to weigh on the present. This begs the question of how ghosts navigate contexts in which time and place are continuously in upheaval. How do ghosts grapple with events (individual and collective trauma), things (material and immaterial culture and heritage, heirlooms, property, personal belongings), places (a territory comprised of its inhabited, built and natural environments), and timelines (histories, individual and collective memories) which are expunged? Palestine remains, in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the most egregious example in which time and place are, and continue to be, structurally erased. The Palestinian historian Nur Masalha speaks of memoricide and toponymicide to designate the cumulative loss of, respectively, Palestinian memory and Palestinian place.4 If anything, these erasures offer ghosts plenty of reason to haunt and demand a redress of the unresolved historical and political violence that has been waged against Palestinians for over a century.5 This ongoing historical injustice, together with unfulfilled political aspiration and a haunted geography of territorial and national loss, resonate with the spectral sensibility of the ghostly. And yet, what will the ghosts of Palestine find once they return to their lands, their homes, their non-existent villages? As in the real world in which Palestinians are barred from returning to their ancestral homes and homeland, so are Palestinian ghosts stifled in their haunting: everything they encounter is new, changed or erased. Without a material reference to haunt, and with so much gone, what remains of the ghost’s raison d’être?

In their solo exhibition Tomorrow’s Ghosts (30 March – 13 August 2023) at Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg, Palestinian-Danish artist duo Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind proffer poetic, but also radical, suggestions on how to manage this conundrum. Sansour, a Palestinian visual artist who studied in Denmark and received Danish citizenship in 2009, and Lind, a Danish writer and philosopher, have collaborated formally since 2016. While the pair has lived in London for over a decade, they remain strongly engaged with the Danish art scene through participation in film festivals and solo and group shows.6 In addition, their work continues to enjoy recognition and support from Danish art funders; Sansour’s 2019 contribution to the Danish Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale — with Lind credited as artistic collaborator — is a particular highlight. Tomorrow’s Ghosts was their first exhibition in Denmark with a shared credit line.7 In the exhibition, Sansour and Lind’s ghosts, contrary to Gordon’s, do not enjoy the luxury to eschew new things: their ghosts have to navigate the new so they can perform their haunting and effectuate change. Known for using science fiction in their oeuvre to unsettle conceptions of time, space and identity, the artists’ use of the ghostly in this exhibition adds an additional layer of complexity. Sansour and Lind cleverly turn the spectral into the speculative by insisting that ghosts not only encroach on the present and the future from the past, but also encroach from the future on the present, and, crucially, from the future on the past. Ghosts from the future, still troubled by the past, kindle revisionist histories that aim to destabilise accounts of the past. Postcolonial studies scholar Anna Ball, writing about Palestinian visual art, points out that in Palestinian art there is a ‘turn toward the spectral as an animating rather than nihilistic force: a means to celebrate the resilience of life-even-in-death, rather than to mourn a condition of death-in-life’.8 Sansour and Lind extend this notion and turn the ghost into a life force, a necessity for animating the past, present and future. The title of the exhibition, Tomorrow’s Ghosts, can thus be read in multiple temporal ways: these are ghosts for tomorrow as much as they are from tomorrow. The ghost in this exhibition, whether a singular figure or a ghostly motif, is always a collective one too, and one that haunts from the past and continues to do so from the future. Science fiction, like inter-generational trauma, produce haunting grounds arising in temporalities that are unaligned, collapse into each other, are deeply troubled and therefore keep on producing their own, often contradictory, temporal logic. As such, the works in the exhibition not only expand notions of spectrality and haunting, the ghost and ghostliness, but, importantly, redefine them. In this review article I trace how the individual works making up the exhibition and the exhibition as a whole do this.

Spectrality and Loss in As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night (2022)

While museums in Denmark engage curatorially with political topics and are increasingly diversifying their programming to include artists from non-Euro-Western backgrounds, institutional solo exhibitions by Arab/Palestinian artists are still rare.9 Tomorrow’s Ghosts was presented in Kunsten’s bunker-like lower-level gallery space and featured three works: the multi-channel video works In Vitro (2019) and As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night (2022), and the installation project Archaeology in Absentia (2016–17). Enveloped by black walls, black carpet and with transparent muslin separating the works from each other, the sparse but effective exhibition design enforced the idea of the viewer entering a series of thresholds that must be crossed [Fig.1]. All three works, in their own specific ways, articulate how the past lingers and sometimes even intrudes on the present and future. However, in all these works the most distinctive conceptual and political gesture comes from the future— where the ghosts from tomorrow seek reparation for the injustices of the past and those of the present. In Sansour and Lind’s work the conceptual framing is inherently ghostly because the violence propelling all works remains unresolved. To a degree, this violence is specified: the death of a child in both In Vitro and in As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night, respectively by ecological catastrophe and by political unrest. Cutting across all three works is the violence of loss of belonging and loss of home. While these works are firmly anchored in the historical and geo-political context of Palestine, their speculative and ghostly underpinnings not only move the works beyond their geo-political framework but also disrupt the extent of what the viewer can comprehend empirically. This diminished comprehension falls in line with Jacques Derrida’s characterisation of the spectral. Namely, as something that is ‘unintelligible, invisible, and uncontrollable’.10 We cannot fully know the ghost because it cannot fully be represented; it therefore does not allow itself to be fully known. This, however, offers opportunities because it ‘provides an alternative mechanism of seeing and hearing and feeling and engaging’.11 The irrepresentability of ghosts in the context of Palestine is further complicated by ghostliness veering between the individual and the collective, therefore multiplying how ghosts manifest themselves. For example, the three-channel video installation As If No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night is a filmic opera in which the protagonist, haunted by grief, laments the death of her daughter. Performed by Palestinian soprano Nour Darwish, the opera combines lyrics and music from Austrian Jewish composer Gustav Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (1901 and 1904) with the Palestinian traditional folk song Mashaal in which a Palestinian woman mourns the enlistment of her loved one in the Ottoman army to fight in World War I.12 When the protagonist grieves for her lost child, she conjures up all children lost to cycles of political violence in Palestine and beyond. The coupling of Mahler’s work bewailing the loss of innocent life with the Palestinian song decrying loss of life to military conflict becomes particularly poignant when considering how many children have been killed in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The onslaught in Gaza following the October 7, 2023 Hamas attacks in Israel is only the most recent example.13

Sound, or rather sound bleed, becomes another subtle way in which individual and collective experience blur and how spectrality ties the exhibition together. Film and photography are often described as spectral media, but so too is sound, specifically in this exhibition. Nour Darwish’s voice, at its highest notes, pierces through the entire exhibition space, while the rumble of In Vitro’s soundtrack provides an ominous low base frequency to the show as a whole. Not only does the invisible, but audible, presence of sound remind the audience that there is something else impinging on their current viewing experience; sound also pulls them away from the present and catapults them into the historical crises of the long twentieth century in As If No Misfortune and in a dystopian science fictional future in In Vitro. In Tomorrow’s Ghosts, sound and image break through linear timelines, forcing us to contend with the fact that the narratives Sansour and Lind offer never solely present singular depictions of trauma, loss and dispossession, but always collective ones too. Sound and image serve as haunting conduits and indicate, to paraphrase Mark Fisher, places that are stained by time and places that encounter broken time.14 Palestine, as a historical, geographical and identity-forming locus, is such a haunted place. It is stained by time in the sense that it is weighed down by a past impossible to return to, while simultaneously it seems bereft of a future, robbed of a continuous timeline as much as it is robbed of its territory. This spatio-temporal dislocation is most forcefully exemplified in the post-apocalyptic video installation In Vitro.

Political, Ecological, and Temporal Hauntings in In Vitro (2019)

Originally produced for the Danish Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale (2019), the black and white two-channel video installation In Vitro shows the West Bank city of Bethlehem — where Sansour grew up — after an ecological disaster [Fig.2].15 An environmental catastrophe has rendered the world uninhabitable and forced the few survivors to live in a bunker underground. I have written elsewhere that this subterranean world is not only haunted by the ghosts of the past but is actually built on it.16 In this work, ghosts are wilfully summoned. The underground world of the bunker finds itself suspended between a traumatic past and an uncharted future. The present seems evacuated, an example of Fisher’s stained and broken haunted time. But space too is made strange and unfamiliar. The bunker is a functional nonplace, geared towards survival and a continuous reminder of what was lost. It stands in stark opposition to the opening sequence of the film, which shows Bethlehem with its many landmarks –such as the Church of the Nativity and Manger Square — before the town is engulfed by a destructive wave of black oil. The bunker, then, is itself a ghostly threshold, a haunted space that cannot manifest itself fully in the present because its existence is meant to be only a temporary solution. It is defined by the destructive event that occurred in the past and simultaneously by a desire to return to Bethlehem in the future. The bunker — and by corollary all life below ground – is ghostly because it is not only haunted by life before the disaster but also animated by it. Life in the bunker veers between being bound to the past and how things were before the cataclysm and hoping for a return to Bethlehem above ground at a certain point in the future. This push and pull between past and future, between desperation and hope, is a plight shared by many refugees, whether they have been driven into exile by war or by another tragedy. In the Palestinian context, there is clearly a time before the 1948 Nakba (the Palestinian catastrophe and dispossession aligned with the foundation of the State of Israel) and a time after. The Nakba, however, did not end in 1948 as dispossession and displacement continue, rendering the Nakba al mustamirrah (continuous) and the present haunted. To put it in sociologist Lila Abu Lughod’s words: ‘the past has not yet passed’.17 This makes thinking about the future from a position of the present particularly challenging. In In Vitro, spatial and temporal disenfranchisement produce an existential disenfranchisement; everything rides on a return above ground that — for now — cannot be obtained. This modality is all too familiar to Palestinians whose ‘awda or return to historic Palestine drives Palestinian political aspiration. A lost homeland is like a phantom limb, missing but still very present, its pain still deeply felt. In Vitro does not shy away from the genuine ache of loss; on the contrary, it speculates that an identity of the present must commune with its ghosts — past and future — to be authentic.

In Vitro’s plot centres around a dialogue between two women discussing memory, loss, identity, belonging and transgenerational trauma. Dunia, elderly and ailing on her sickbed, is played by renowned Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass, and Alia, a clone engineered from the DNA of those who perished in the ecological disaster, including Dunia’s deceased daughter, is played by Palestinian actress Maisa Abd Elhadi [Fig.3]. Dunia calls for a return to life above ground, her ‘awda. It is of essence for her to keep the memory of the past alive. Moreover, her idea of the future is a future cast in the image of the past and a return to an idealised time before the apocalypse. Only a full return can constitute the means to heal. For her, ‘this present barely exists’.18 Conversely, for the clone Alia matters are less clear. While through the cloning process she inherited the memories and trauma of those who died, all she knows empirically is the reality of the present: the bunker, the lab she was artificially grown in and the underground orchard that provides sustenance for the surviving population. Both Dunia and Alia are haunted by memories of the past, with the difference that Dunia embraces them as an existential raison d’être and Alia rejects them. In a testy exchange, Alia retorts: ‘[T]he past spoon-fed to me … my own memories replaced by those of others. They appear personal and intimate. They’re not real but seductive … like lavish illustrations in a children’s book. Out of touch with life down here like a bacteria planted in me’. Both women demonstrate how they are affected differently by these hauntings. While Dunia is very much a spectre of herself, gaunt and on her deathbed, clinging to an identity of a destroyed world, Alia could be seen as the ghostliest figure of the two. As a clone, she personifies the spectral by being both revenant (bringing back to life those who died during the catastrophe) and arrivant (a manifestation of a possible future for those in the bunker).19 Alia strongly affirms, ‘I don’t believe in ghosts. What we are doing here will not restore the past’. However, she herself mobilises the idea of the ghost into a radically emancipatory proposition. She literally is ‘tomorrow’s ghost’: a ghost for the future and from the future. A figure in search of an authentic identity who straddles all temporal plains of past, present and future and who insists on harnessing the present while refusing to be shackled by the past. ‘Perhaps a loss of memories is essential to starting over?’, she carefully suggests, while admitting that the memories artificially implanted in her are ‘too vivid to dismiss as somebody else’s’. If the ghostly is characterised by ambiguity and unresolvedness, then Alia personifies it. At the same time, it is by inhabiting the ghostly with all its contradictions that Alia might manage to identify a horizon of hope and, eventually, undo the haunting.

Though at a first glance In Vitro’s aesthetics seem clear-cut — the split screen, the formalism of black-and-white cinema, the dreamy scenes of life before catastrophe [Fig.4] vis-à-vis the austere functionality of life after catastrophe — they are in fact highly ambiguous and ghostly. Here the oppositional aesthetics become a haunted aesthetics. Past, present and future do blend into each. Memory and forgetfulness are not each other’s opposites but rather two sides of the same coin that in In Vitro seems to be continuously spinning. For someone whose drive is fully centred around remembrance, Dunia concedes: ‘We spent too long registering, recording, archiving’. The archival footage of early twentieth-century to 1967 Bethlehem included in the film is a case in point. On the one hand it serves to anchor historicity in the film’s suspension of disbelief, transporting the viewer momentarily back to the ‘there and then’ in Palestine. But on the other, the archival material also very much produces a sensibility of ‘here and now’. Is the grainy black and white footage of refugees crossing Allenby Bridge following the 1967 war in which Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and the Sinai desert any different from the even grainier footage of those who fled in the 1948 Nakba, or for that matter the high-definition images we see on our screens of internally displaced Gazans in Israel’s most recent war on Gaza (2023–2024)?20 The archival footage does not necessarily mark something that lies in the past. Rather it underscores that ‘the past [is] still at work within the present, still actively re-engendering it in its own shape,’ as long as the historic and epistemic violence against Palestinians continues.21 The role of the archival material, a recurring feature in Sansour and Lind’s work, harks back to Dunia’s question about the sense of archiving in the wake of obliteration. Do all these materials – in Alia’s terms ‘a liturgy chronicling our losses’ – lay the ghosts to rest, or do they actually spur them on? If the Nakba is al mustamirrah (continuous), can the work of mourning, essential to working-through trauma and restoring agency, take place at all?22 This fundamental question is provoked in the three-channel opera As if No Misfortune Had Occurred in the Night.

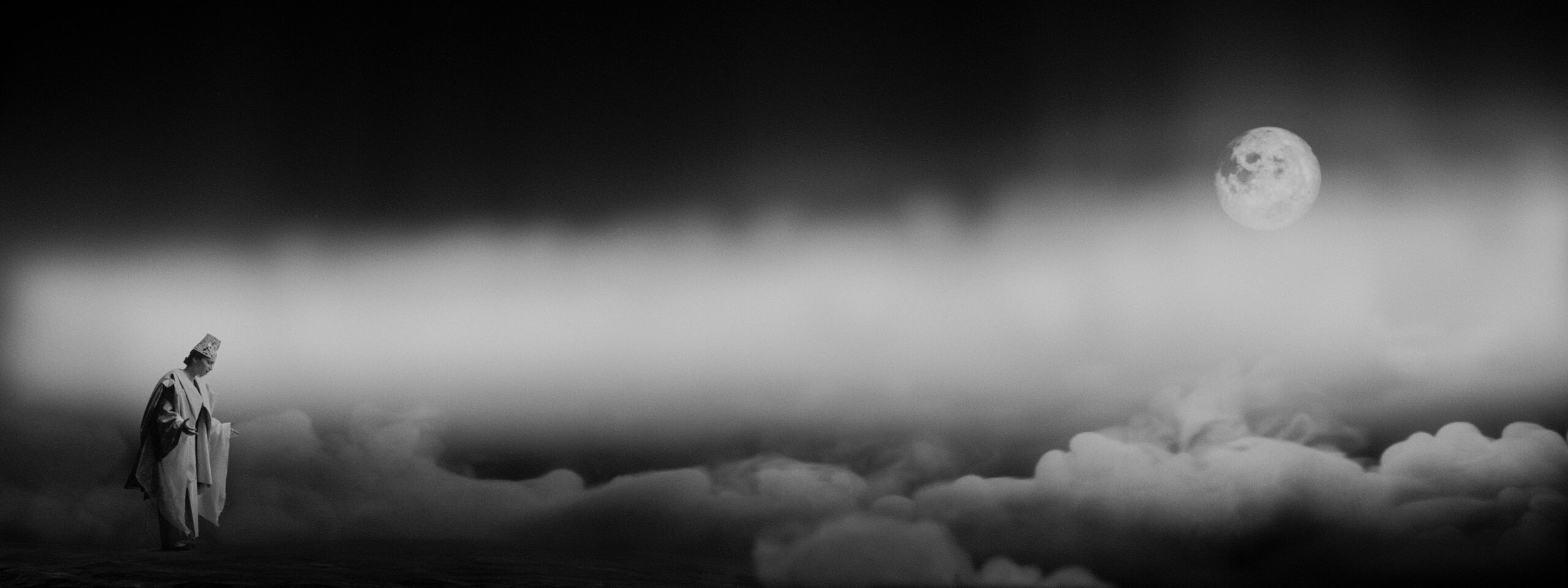

Here, too, the artists employ split screens, black and white film, and archival material, and here too these aesthetic and conceptual choices serve to mobilise the ghostly. Set in a derelict and wind-swept church with light faintly peeping through its stained-glass windows, the setting is decidedly haunted. It is sacral but ruinous. Whereas in In Vitro the bunker, with all its impediments, still struggles to be a place of life, a place where survival might grow into a new beginning, the church in As if No Misfortune is a site of absolute loss and mourning. Like In Vitro’s Alia and Dunia, the protagonist (soprano Nour Darwish) casts a haunted figure, a mother grieving for her dead daughter. In this work too, individual loss turns into collective grief. ‘I mourn not only the losses I can count but also those ahead and yet unnumbered,’ Darwish sings standing on a ghostly plain of misty clouds, a moon peering through the right-hand corner [Fig.5].23 The child’s absence is further accentuated by the image of the protagonist being mirrored across the two outer screens, rendering her an apparitional double and making the void the child left all the more potent. The mother becomes a phantom herself. In a scene towards the end of In Vitro, Alia remarks about her memories: ‘some scenes are more grainy and faded than others,’ as if she were describing their ghostliness. This is put into practice in As if No Misfortune. Veering from a full shot across all three screens to a detail shown blurred on a single screen, the image is unclear: parental grief, as well as all the other mournful losses the protagonist has accrued, cannot be fully visualised. The mother’s memory of her child persists, albeit devoid of an image. Instead, other images suggesting absence — imperfectly — fill that gap. For example, there is a shot of a rocking chair swaying back and forth with no one on it; a candle’s wick flickers in the draft; the sound of a closed door creaking open while in fact it remains shut. These ghostly scenes signify the Palestinian predicament that walks that brittle line between privation and aspiration, between something that is materially present (the territory of historic Palestine) yet absent (a nation state).

In As if No Misfortune, like in In Vitro, the archival material yanks the viewer from any kind of reverie and demands we look at this work with a historical eye: with the eye of the present but also with a speculative eye from and for the future. Most of the footage, mined from the collections of the Imperial War Museum in London, is from early twentieth-century Bethlehem and Jerusalem. For example, the iconic views of the Mount of Olives with the golden cupola of the Dome of the Rock are easily recognisable; so too is the imagery from World War I with its trench warfare. Whereas the Nakba is often cited as the starting point for Palestinians’ collective trauma, or as Lena Jayyusi so eloquently puts it, their ‘lesion with memory,’ the artists point to a longer historical arc.24 The period of World War I and Palestine transitioning out of Ottoman rule are set as the stage for the creation of the State of Israel and the dispossession of the Palestinians. The first two decades of the twentieth century and particularly the collapse of the Ottoman Empire were pivotal for the formation of a Palestinian national consciousness.25 Similar sentiments for independence were brewing across the region following the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement in which France and Britain partitioned the Middle East in French and British spheres of influence and control.26 However, in Palestine, growing Zionist immigration and the 1917 Balfour Declaration, promising a national homeland for Jews in Palestine but no political or national rights for its indigenous population, accelerated Palestinian national identity formation.27 Many Palestinians were drafted into the Ottoman armies to fight the allied forces. As if No Misfortune points to significant historic factors prior to, and beyond, the Nakba that keep on haunting the present and the future. In an arresting scene, the protagonist stands in a forest of dead suspended tree trunks. She sings: ‘The cataclysm of a century ago revisited in eternal sequels. Paying off their losses for decades yet to come’ (emphasis mine) [Fig.6]. In another scene using archival footage, a tank crushes a bed of cacti. The latter is not meant to be a minor detail. Rather, cacti and their fruit, the prickly pear, signify steadfastness in Palestinian national discourse and art. Following the Nakba, cacti were planted around erased Palestinian villages, a ruinous and ghostly marker of what once was.28 As if No Misfortune is filled with such markers of absence and loss that seep from the past into the future, and as a form of proleptic mourning, as Darwish sings of losses ‘ahead and yet unnumbered,’ from the future into the present.

Whereas in In Vitro the ghostly still seeks a new beginning and formulates a forward-looking stance through clone Alia, in As if No Misfortune the prospect of a horizon, and therefore of the future, seems fully lost. Alia desperately tries to harness the present and establish an identity for herself in the future. In the opera, however, all command over time seems relinquished and what remains is a ghostly existence out of time. The protagonist sings: ‘Ejected by time and stripped from our chronology. This haunted present recites the prelude to our slumbering history’ (emphasis mine). In the video’s closing sequence, in a dramatic gesture the performer dismounts her headdress, rips her bodice — recognisably decorated with tatreez (traditional Palestinian embroidery) — and steps in a pool of indigo-coloured water, the only colour element in the entire work [Fig.7]. The final scenes of the opera are sung in indigo-dyed clothes, the rest still black and white. Dyeing clothes indigo is a traditional mourning ritual in Palestine.29 If In Vitro is characterised by a loss of identity and belonging, then As if No Misfortune is tormented by a profusion of it. Both works, nonetheless, demonstrate mourning and haunting caused by intergenerational trauma. In both cases, identity, if not ontology, is at stake.

Emancipatory and Reparative Ghosts from the Future

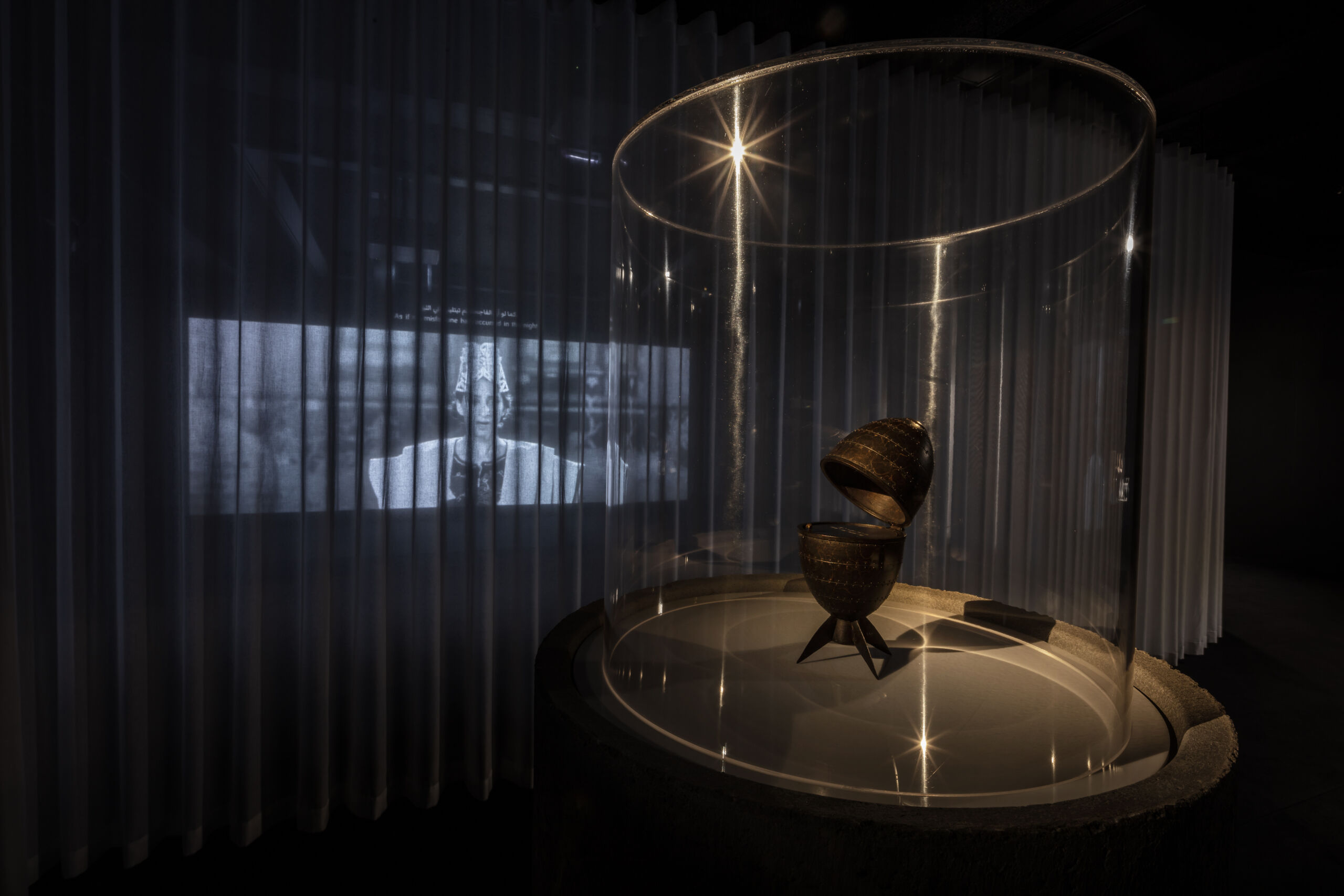

Anthropologist Heonik Kwon characterises ghosts as ‘ontological refugees’. They are ‘uprooted from home, which is to them a place where their memory can be settled’.30 On the one hand Kwon underlines the inextricable entanglement of identity and memory, on the other he points to an unsettledness of being and of place. All this is galvanised in the Palestinian condition and the denial of a homeland. Palestinian exile concerns as much identity and memory (in Masalha’s words the ‘memoricide’ of Palestine) as it does place (in Masalha’s words the ‘toponimicide’ of Palestine). In the sculptural installation Archaeology in Absentia (2016–17), Sansour and Lind reverse engineer this relationship by projecting memory in the future. Placed between the two video installations in the exhibition, this project articulates the boldest step yet: how to mobilise the ghostly in an emancipatory way. Its strategic placement between the uncertainty of In Vitro and the utter loss of As if No Misfortune proposes a radical owning of the ghost: one where disaster is not necessarily passed on from one generation to the next, but rather becomes agential and transforms the future by, paradoxically enough, transforming the historicity of the past. Both In Vitro and As if No Misfortune question whether genetic make-up equals destiny. For example, in the latter the protagonist sings: ‘I didn’t invite the demons in. Yet they rummage through my veins’. Archaeology in Absentia affirms that this does not need to be the case. The sculpture series exhibited in Tomorrow’s Ghosts is part of a larger body of work revolving around the single-channel science fiction video In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016). In the video, a resistance group makes deposits of elaborate keffiyeh-patterned porcelain in the hope the tableware will be found in the future by archaeologists. This would create material and historical evidence of the existence of a people who, indeed, ‘ate from the finest porcelain’. The project comments on how archaeology, and specifically biblical archaeology in Israel, is weaponised to construct origin myths and land rights exclusively for Jews.31 In Archaeology in Absentia, that weaponisation is flipped and made material. The installation consists of fifteen 20 cm bronze munition replicas which resemble Fabergé eggs. Each ‘egg’ contains an engraved disc with the longitude and latitude coordinates of where their load of porcelain has been deposited and buried in historic Palestine [Fig.8]. The sculptures, then, are testament to the ghostly geography of a Palestinian map that no longer exists, but they also simultaneously attempt to reclaim it.

At Kunsten, Archaeology in Absentia was installed on individual cylindric concrete pedestals with spotlights trained on the Perspex-encased munition shells. With the metal surfaces subtly catching the light, this particular display evoked both the sensibility of protecting valuable archaeological artefacts and a precious series of embryos growing in a test tube [Fig.9]. Past and future amalgamate and live in a single object. With the porcelain itself absent from the installation and scattered across historic Palestine — from Jerusalem, Acre, Haifa, Jaffa, and Nazareth in present-day Israel to Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Jericho in the West Bank — the absent presence of Palestinian exile is reproduced. Lind, courtesy of his Danish passport, was able to enter Israel and plant porcelain there, a privilege not afforded to Sansour, who has been banned from visiting Israel and the city of her birth, Jerusalem. While these empty shells are haunted by loss, they also — in a ghostly fashion — reconstitute it. This recalls the late Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s (1942–2008) celebrated autobiographical prose poem Absent Presence (Fi hadrat al-ghiyab, 2006). In this hybrid piece of writing, prose and poetry converge, lived experience and the imagination become one, and the recording of his own demons echo the collective haunting of the Palestinian people. The work is, as Anna Ball observes, ‘inhabited by images of a spectral Palestinian past that refuses to be laid to rest […] in which the fraught relationship between presence and absence, visibility and invisibility, past and present [are] also at stake’.32 This accurately describes what happens in Archaeology in Absentia. Moreover, the refusal of the porcelain to be laid to rest is its raison d’être. Without being disinterred, becoming visible again, and telling the story of a people threatened with erasure, it has no function; it has to resurface. Another aspect also drives Archaeology in Absentia to ‘commune,’ as Ball puts it, ‘with Darwish’s ghosts’.33 The complex dynamic between presence and absence signifies and denounces the legal category of ‘present absentees,’ created in 1950 by the State of Israel.34 This spectral term, part of Israeli Absentee Property Law, refers to Palestinians who were absent from their homes during the Nakba and whose properties were confiscated by the state while they themselves still were present in Israel, turning them into internally displaced refugees.35 Present absentees, like many other Palestinians who had to flee to neighbouring countries, are effectively condemned to a haunting existence, residing in close proximity to their homes but unable to return. Archaeology in Absentia embodies all these spectral contradictions but offers reparation: in the future, and through the will of the imaginary, ghosts will be laid to rest. In Archaeology in Absentia, ghosts reconfigure the future.

However haunted Tomorrow’s Ghosts might be, it is ultimately a project of repair which invites ghosts to speak up and speak back by lending them a voice, agency and subjectivity. These ghosts continue to linger and haunt Palestine’s landscape and Palestinian national consciousness; how could they not with so much still left unresolved? Tomorrow’s Ghosts offers them, at least, an imaginary place to return to. This makes the exhibition very much an exercise in spectral co-existence: being and living with ghosts. As Alia in In Vitro demonstrates, this is not always harmonious. Still, Alia endeavours towards accepting the ghost as kin and as an intrinsic part of herself, and therefore her future. Co-existence also means acknowledging each other’s pain as a first step in the process of healing. As if No Misfortune shows how individual and collective hurt and haunting are entangled and pulsate violently through past, present and future. Addressing, and dressing, these wounds that continue to tear through Palestinians’ lived experience is a prerequisite to start offering ghosts, these ‘ontological refugees,’ a home. To live with ghosts means to see them. In Tomorrow’s Ghosts, Sansour and Lind open up this field of vision and demand their audiences see them too.

The research for this article was supported by Kunsten, Museum of Modern Art Aalborg in connection with the exhibition Tomorrow’s Ghosts (20 March – 13 August 2023). The author thanks the anonymous peer reviewer for their insightful comments.