Summary

This article looks at the works Wilhelm Marstrand created in connection with his stay in Venice in 1853–54, and analyses the characteristics of Marstrand’s working method, choice of subject matter and role on the Danish art scene in light of the period’s National Romantic trends and the prevailing expectations held of academic painters. To put Marstrand into perspective, the article also addresses his friend and fellow artist Peter Christian Skovgaard (1817–75), who stayed in Venice at the same time as Marstrand. The article illustrates how their works embody their different approaches – one being a figure painter, the other a landscape painter – and how the period’s discussion about the national sentiment in Danish art has coloured the reception of both of these Danish painters’ Venetian images.

Articles

The historicist façade of the National Gallery of Denmark overlooks the square known as Georg Brandes’ Plads and the noisy traffic of the Sølvgade junction in Copenhagen. A few years after the museum moved here in 1896, Wilhelm Marstrand (1810–73) was prominently represented outside the museum itself in the form of a nearly three-metre tall bronze statue placed next to the monumental staircase. On the other side of the stairs, a statue of Herman Wilhelm Bissen was erected (1798–1868).1 The sculptures depicting the two artists were intended to embody the finest that Danish art – painting and sculpture, respectively – had to offer. However, since then, Marstrand’s reputation has waned considerably, and the statue of him no longer towers in front of the National Gallery. Following a modernisation of the museum’s entrance in 2013, both statues were removed and put into storage. [fig. 1] However, the 900 works by Marstrand housed in the National Gallery’s collection testify to an artist who still figures prominently in the narrative of the Danish Golden Age, even if opinions on the quality of his works are divided today.

Marstrand is known for many things, including cheerful scenes from Italy. He travelled to Italy a total of four times, but the works created on his third voyage, a stay in Venice in 1853–54, have been less well elucidated than those from his two previous sojourns in Italy in 1836–1840 and 1845–48. Nevertheless, the 1850s are interesting years in Marstrand’s career. During this period he was involved in the controversy and strife associated with a reform of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and the increasing trend for expressing national sentiment, partly as a kind of aftermath of the First Schleswig War – also known as the Three Year’s War (1848-50) – which would have an effect on his work. It was also a time when he had achieved recognition and success, yet was beset by doubts about his own abilities and achievements. Marstrand’s trip to Venice eventually saw him stay there for approximately a year just after he had been appointed director of the Academy. In his letters home, he shared his deliberations on his own work and on the conditions cultivated for art at the Danish Academy.

To provide an illuminating contrast to Marstrand, the article also includes his friend and fellow artist Peter Christian Skovgaard (1817–75), who, with his wife Georgia Skovgaard (1828–68), spent a month in Venice during Marstrand’s stay. While there, the Skovgaard couple socialised with Marstrand and his wife, Grethe Marstrand, née Margrethe Christine Weidemann (1824–67). Their letters and works from these two journeys are primary sources aiding our understanding of Marstrand as an artist, offering insight into how he and Skovgaard acted in times of artistic turmoil. Here, I wish to highlight the connection between Marstrand and P.C. Skovgaard and how their works demonstrate different approaches to their subject matter, predicated on the former being a figure painter and the latter a landscape painter.

The Danish Golden Age artists’ travels and works in Italy have been described several times over the years, with scholars addressing them from different angles. Often, however, art history literature has focused on their stays in Rome and the period before 1850.2 More recent literature has applied a different approach to the painters’ pictures and letters from Italy, adopting a sociological-ethnographic perspective based on the concept of tourism.3 Other studies have challenged older art history’s assessments and judgements of the artists or parts of their oeuvre,4 as expressed in e.g. Karl Madsen’s (1855–1938) and Theodor Oppermann’s (1862–1940) monographs about Marstrand, published in the early twentieth century.

Aiming to do something other than the literature listed above, I will consider Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s works in light of the period’s discussion concerning distinctly Danish, national aspects in art,5 and how it has tinted the reception of the two Danish painters’ Italian pictures from an age traditionally described as the point of transition from Denmark’s Golden Age to the National Romantic era.6 This article takes a closer view of the works Marstrand created in connection with his time in Venice in 1853–54, analysing his choice of subject matter, working process and role on the Danish art scene. While these particular Italian pictures are described in existing literature, they have not been considered in great depth before.7And as far as Skovgaard is concerned, the works dating from his time in Venice in 1854 have also only been subjected to limited scrutiny.8 Even though both artists were enchanted by Venice, they also express great love of their native country. Hence, their art and letters speak of love of Italy – but this love is firmly rooted in a National Romantic outlook on Denmark.

From the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art to Italy

Wilhelm Marstrand trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, studying under Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783–1853). In 1833, he was awarded the Academy’s major silver medal, but he never got the gold medal, which would have won him a travel grant traditionally used for a Grand Tour with Italy as its goal. Instead he applied, in 1836 and at the recommendation of the Academy, for a grant from the foundation known as ‘Fonden ad usus publicos’ and received enough funding to allow him to spend several years in Italy. Thanks to this support, he ended up staying in Italy, mainly in Rome, from 1836 until 1840. In 1845 he set out on his second trip to Rome, staying there until 1848.

Upon returning from his second voyage to Italy in 1848, Marstrand was appointed professor at the model school at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. His later trip to Venice differs from the first two by taking place at a point in Marstrand’s career where he was an established and acclaimed name, yet also an artist who continued to express uncertainties about his own artistic abilities and was anxious about living up to the expectations held of him from home. The acclaim and expectations only grew even greater when Marstrand was appointed as the new director of the Academy in Copenhagen in 1853. However, he began his directorship by applying for a year’s leave to travel to Italy. He left his wife Grethe and their two-year-old son Poul (1851–1902) back home in Copenhagen, partly because travelling with the entire family and a maid would be expensive, partly because the journey would be hard for the little boy and for Grethe, who had just lost a newborn daughter and was believed to be pregnant again.9

Regarding the reason for his leave, Marstrand stated that he needed ‘to retreat into myself for the sake of my art — I had become a little too embroiled in everyday hassles and nonsense and had not felt it sufficiently incumbent on me to carry out serious and concerted work. But now I will surely get back into my stride’.10 ‘The everyday nonsense’ was probably the reform of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts that had been underway since 1850. The reform efforts reflected a shift in the positions of power on the Danish art scene, a gradual move away from certain artists and artistic modes of expression to others. A change was coming in terms of the kind of artists and the kind of art that could be accepted and acknowledged at the academy. Up until this point, candidates wishing to become full members of the academy had been required to paint a subject chosen by the existing Academy Council, who would subsequently judge the quality of the admission piece, either accepting or rejecting it. There was also an upper limit to the number of members the academy could have.11 This meant that younger, hopeful artists had difficulties in being accepted as members. They had to comply with an older generation’s view of art both in terms of style and subject matter. Responding to this, a commission was set up, and part of its task was to propose a new method of selecting members for the Academy Council. By 1853, the commission had finalised its proposal for a reform, but Marstrand, the newly appointed director, surprisingly took leave and left the country. In doing so, he left the commission, their proposals and the reform efforts in something of a vacuum. Writing from Venice, Marstrand wrote the following to Skovgaard, who was still in Denmark at the time:

Thank you, my dear friend, for the letter and your pledge of constancy and brotherhood in these times. I think that the very best thing for strengthening and maintaining one’s desire for art is to treat it seriously in one’s demands on one another; for it is pitiful to see how little the world demands. – When I think about it, I feel more like laying down my brush, lying on my back and dreaming of one thing and the other […] By the way, there is a horrible fracas in the institution after Thiele’s letter and God help them and me, and those who put their trust in me. I take no pleasure whatsoever in thinking of that institution […]12

The paradoxical aspect of Marstrand’s relationship with the ‘Institute’, as he calls the Academy, is that he let himself be appointed director out of all the other professors there, yet took no pleasure in the responsibility. He had an equally ambiguous relationship with the expectations placed on him by the Danish art scene. On the one hand, he was strongly engaged in the art world and in the community formed with the other artists, on the other hand, he wanted to stop being an artist altogether. His trip to Italy thus not only gave him the peace and quiet he needed to work with his art; it also gave him respite from the struggles concerning the conditions in the art world in Denmark. When Marstrand returned from Venice, he wrote the following to Skovgaard, who was still in Italy:

I would ask you to gird yourself, to be prepared to carry your shield and lance forth into the realm of artists, for there is war going on there as there is in so many other aspects of life, and it is difficult to say what the outcome will be. Informing of you all the ins and outs of the matter would be too cumbersome here, and would also be a pity, as you are presumably engrossed in your Italian dreams – but you must join the struggle now; you are sorely needed.13

However, the struggle lasted until 1857, when a reform was finally adopted in September. Membership of the academy now no longer required the approval of an admission piece, but could be effected through the recommendation of two existing members – and it was also possible to make an ‘unsolicited’ request to become a member. When it was time to appoint a director according to the new regulations, Marstrand lost the election to J.A. Jerichau (1816–83).14 Finally, Marstrand could lay down his shield and lance and once again pick up his brush, having gotten the peace and quiet necessary to focus on his painting.

From sketch to finished painting

During the Danish Golden Age of painting, artists would typically begin by making pencil, pen or watercolour sketches which were later converted into light oil studies, often made on cardboard, which then formed the basis for fully finished paintings done in oil on canvas. Only the latter were intended to be submitted for admission to the annual juried exhibition at Charlottenborg, while the other works were simply stages in the working process that were only shared and shown in art circles where no jury adjudged the works.15 In Marstrand’s own day, his carefully finished paintings were much appreciated – they matched the academic requirements of the age. However, later art historians such as Karl Madsen and Theodor Oppermann particularly liked his sketches and oil studies. In 1905, Madsen wrote:

Marstrand’s art has a major strength and a fundamental weakness. A perfect and incomparable master of subtle hints and intimation, he did not acquire the same mastery of the form in the final execution. The loose drafts of his drawings and sketches are far superior to the finished paintings.16

In 1920, Oppermann expressed similar sentiments, stating that ‘in his sketches and studies especially, [Marstrand] reveals a truly remarkable eye for colour; however, this would sometimes fail in his finished pictures’.17 In recent times too, his studies have elicited the most positive responses in art criticism, being reminiscent of the new departures within painting seen in the late nineteenth century. In 1992, for example, Poul Erik Tøjner (1959–) commented that ‘according to a modern concept of art, his sketches are significantly better works of art than his finished pieces’.18 The different judgments passed on Marstrand’s work in his own day and in posterity speak eloquently about the different expectations held of art through the ages, but they may also reveal the horns of a dilemma faced by Marstrand, one which may have found expression in his vast production of sketches prior to the finished paintings.

The transition from one medium to the other may be interpreted as Marstrand’s strategy for navigating an art scene that imposed clear requirements on any given painter’s work. In his multiple capacities as professor, director and painter, Marstrand formally played by the rules. He knew what and how to paint in order to satisfy the Academy’s jury and the important patrons. However, his pictures and letters from his time in Venice also show an artist who fought to assert his own creative work process and his joy in more popular choices of subject matter at a time when history painting and the academic aesthetic were still most highly valued. One gets the impression that Marstrand’s creativity and joy in his work were embedded in the many sketches and studies, while the execution of the fully finished works was a labour of duty rather than love. Writing home from Venice to his brother Troels, he said: ‘I have spent a long time now humming and hawing over which picture to embark on out of the many I have drafted, and I have been most dejected’.19 He clearly has no problem creating drafts for many pictures, but translating them into finished paintings disheartens him.

A number of Marstrand’s pictures from Venice can now be found in the collections of Danish art museums, from pencil drawings in sketchbooks to ink drawings and watercolours to painted studies. However, only very few of his fully finished paintings featuring Venetian subjects can be found in public collections. In accordance with the judgments passed by the critics mentioned above, the museums have preferred Marstrand’s oil studies. However, searching the photo archives of Danish National Art Library as well as auction catalogues unearths far more paintings by Marstrand from Venice than can be found in public collections, allowing us to form a more accurate overview of Marstrand’s production from the Queen of the Adriatic.

Postcards from Venice

Marstrand’s original destination for his trip in 1853–54 was Rome. Stopping along the way in Venice, he was enchanted by the wealth of subject matter offered by the City of Canals. He wrote: ‘here [in Venice] I should like to stay for a while; in addition to being entirely new terrain for me, it is most exceedingly picturesque’.20 Around the turn of the year 1853–54, the Marstrands corresponded back and forth, debating whether the family ought to join him in Venice or whether they should remain separated; a discussion that included the financial aspects of the matter. When February brought gentler weather, Marstrand travelled back to Denmark to fetch Grethe, their son Poul and the family’s maid, Mathilde. Setting out for Venice, they arrived there in March 1854 and stayed until the early autumn of that same year.

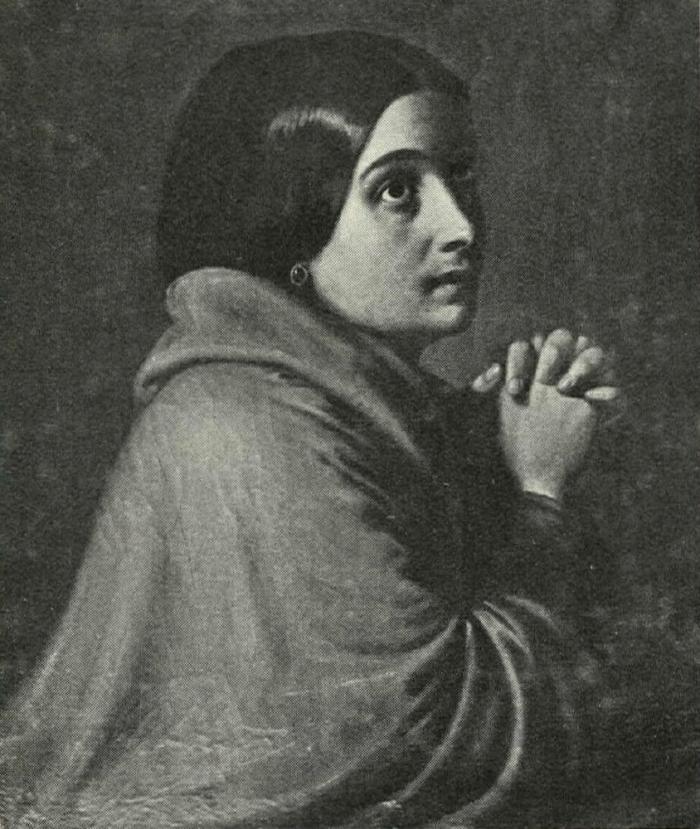

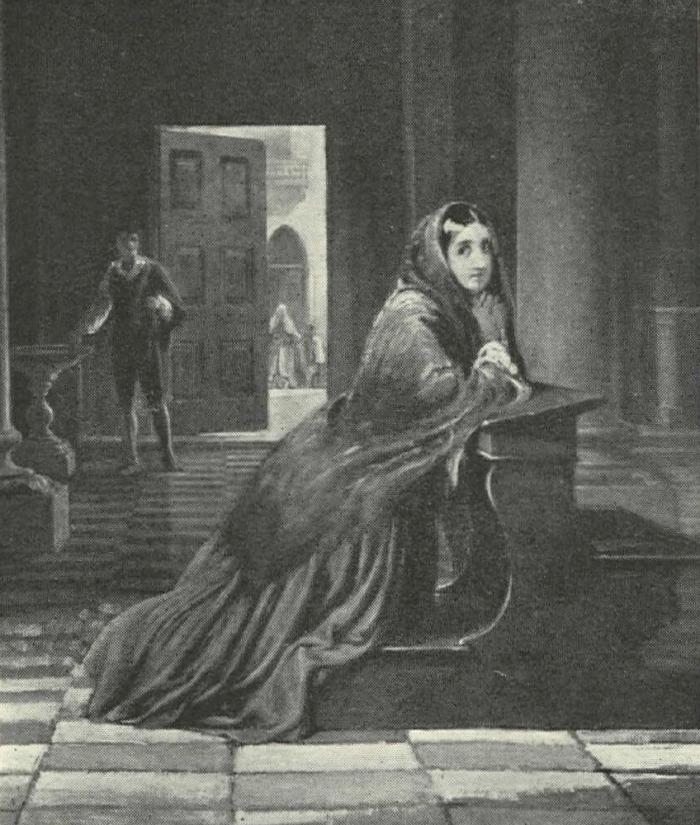

At this point in time, Venice was under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian emperor, and the winter of 1853–54 was unusually cold. Accordingly, Marstrand worked indoors, focusing on a number of pictures featuring local models. Today, we know of a few male portraits and figure scenes depicting various women. He did a study of a Venetian woman in a prayer chair in a church, depicting her in a portrait [fig. 2] as well as a full-length picture [fig. 3] showing the prayer chair and the church. In addition, he painted a portrait of a younger, red-haired Venetian woman at her toilet [fig. 4]. The same woman appears in a study [fig. 5] and a finished painting [fig. 6] of two women in a church. These subjects feature several examples of the contrasts with which Marstrand worked in many of his paintings, and which he also used in his Venice scenes.

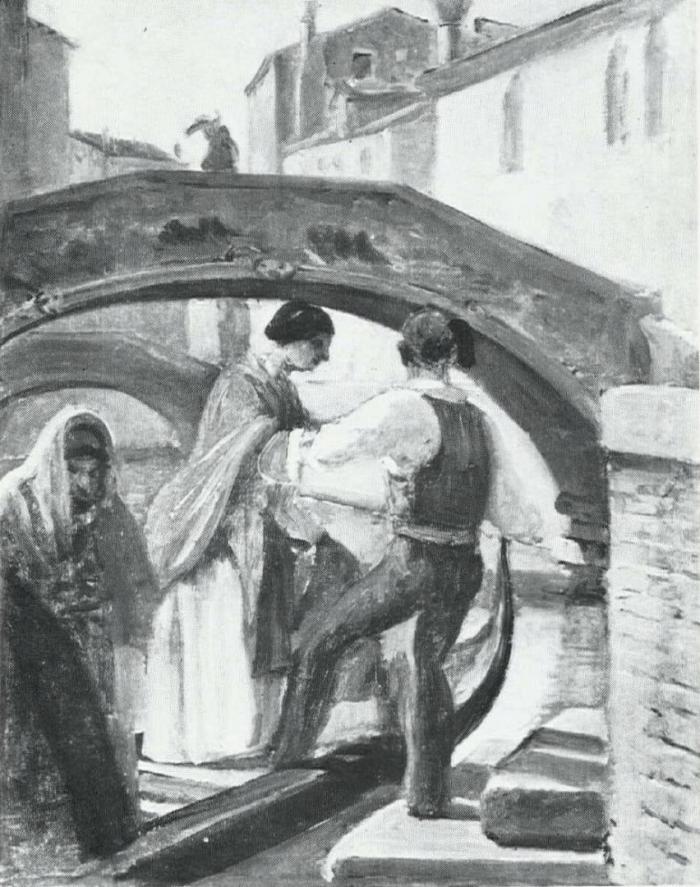

The red-haired woman has fair skin and wears a blue silk dress and a black lace shawl over her head, while the other woman is darker in complexion, has dark, uncovered hair and wears a red shawl. The woman in the prayer chair is lit up by a ray of sunlight that illuminates the otherwise dark church space, and behind her we see a man in front of a half-open door through which light shines in. An outdoor scene shows two fishermen and a young woman [fig. 7]. The fishermen’s lively facial expressions and gestures form a marked contrast to the young girl, who looks shyly into her apron, clutching it with both hands.

In these scenes created with the use of models, Marstrand accounted for some of the distinctive features of Italy: the interiors found in Catholic churches, complete with prayer chairs, and the elegant dress of wealthy women adorned by silk and lace. At the same time he also created his first scene showing the lives of working people by depicting the fishermen and the girl, capturing how the ubiquitous water of the lagoon creates very special lighting conditions in the city. In January he wrote home to Grethe:

Sunshine and light reflecting off the water; it is quite incredible; most eminently scenic and landscape-like – or do I mean waterscape. […] Oh, how beautiful it all was at sunset this evening, I cannot describe it; there is a magic to the light that I have never seen anywhere else and I cannot properly grasp in what, precisely, it resides – whether it is the water reflecting the light, or whether the air has a special transparency here I cannot say. Nor have I ever seen it painted. I see the same colour of air, only in a different way, in Titian’s pictures and Poul Veronese. These colours are not to be believed.21

A generation later, it would be Skagen, the northernmost part of Denmark, which inspired Danish artists with its distinctive light and its meeting between land and water, but for Marstrand, Venice was the place that fascinated him with its special light conditions. He created a range of scenes awash with the light of the setting sun, testing his technical skill up against the evening light of Venice. A study and a finished painting testify to his efforts. The study is a compact, yet light scene in which a gondola almost reaches from side to side [fig.8]. The gondola and the figures in it form a dark silhouette against the golden background, which boasts the outline of the imposing Church of Santa Maria della Salute. In the final version of the subject, Marstrand opted for a more classical approach to composition and cropping; he no longer crops off the spire on the dome of [fig. 9]. The beautiful arch described by the gondola in the sketch has become somewhat flattened in the finished scene. A few stone steps have also been introduced in the foreground to the right as a repoussoir element to increase the sense of depth, and the figures have been painted in brighter, clearer colours so that they appear less silhouette-like. In the finished painting, the characters wear strategically arranged red garments that stand out against the dark church, while some bluish clouds have been added to the yellow sky. While the sketch is hazy and atmospheric, the final image looks rather more like an idealised tourist postcard. If one were to compare the two paintings to photographs, the study is reminiscent of a blurred snapshot: its cropping may be a little haphazard and the colours rather faded, but it poignantly captures the mood of a beautiful evening on the lagoon. The finished painting is like a professional photograph: every detail is razor sharp, and all elements have been deliberately staged, coloured and composed; figuratively speaking, the expressions are exactly right, but the smiles have also somewhat stiffened. Marstrand knew that the customers and critics of his time expected the latter, and he delivered – but one nevertheless has the feeling that he took more pleasure in the first part of the process.

Marstrand’s pictures contain elements that very clearly identify the scenes as Venetian, reflecting how customers back home had to be able to find the famous monuments and other emblematic traits – whether real or imagined – in the artists’ pieces of Italy. Accordingly, he did typical subjects of the kind that would sell well at home.22 Like so many others, Marstrand was fascinated by the city with its many canals, a place where all transport is conducted either on foot or by water. However, being captivated by the sight of the city was one thing; reproducing it was quite another. In this regard, Marstrand alternated between fascination and despair. In a letter to the painter Jørgen Roed (1808–88) and his wife Emilie Mathilde Roed (1806–94) he wrote:

You would surely, Mrs Roed, take much joy in Venice with its wonderfully beautiful palaces and lagoons, but you, Roed, would, like me, feel the great pain of feeling obliged to paint these glories and – finding you cannot.23

Although he stated that he could not, Marstrand nevertheless painted the city’s glories several times during his stay. The many studies may not only be the result of a productivity spurred on by joy and desire, but also by repeated attempts to capture those Venetian scenes that impressed him, reworking them until he was satisfied. When faced with the empty canvas, Marstrand did not freeze up – quite the contrary, he attacked it again and again, not unlike Cervantes’s character of Don Quixote repeatedly fighting windmills, a subject that became another favourite theme of Marstrand’s. He did a number of scenes devoid of staffage as studies to be used for backgrounds in his paintings.

A bridge across a canal painted in a landscape format [fig. 10] is used as a background in an upright study of a young man helping a young woman out of a gondola while an elderly woman stands in the background [fig. 11]. Forming an arch above their heads, the bridge brackets the scene in a way that is utterly characteristic of Venice – an effect similar to having one of its famous churches appear in the background. We do not know of any finished version of this subject, but the same types are repeated in two other pictures, one of which is a study [fig. 12] while the other is a finished painting [fig. 13].

Here, Marstrand once again used the Santa Maria della Salute as a backdrop for a scene depicting a young man helping a young woman out of a gondola while an older woman is also aboard. The finished painting is dated 1857, three years after Marstrand left Venice. The rounded steps seen in the sketch have been replaced by square ones in the finished work, accentuating how Marstrand – like other painters of the time, such as Skovgaard – would deliberately construct his subjects to achieve the desired effect and composition.24

Marstrand’s variations on the same theme, moving and changing different elements from one scene to the next, speak of an artist who did not reproduce reality as he saw it, but reality as it was to be seen in order to meet his era’s expectations of an effective composition imbued by balance, dynamics, depth, colour and drama. In his finished paintings Marstrand is a sampler, picking individual pieces out from his repertoire to deliberately build compositions that would best appeal to the arbiters of taste back home in Denmark.

The backside of the glossy postcard: Beggars, tourists and musicians

While in Venice, Marstrand worked on a series of images of wealthy Venetians being beseeched by beggars. A number of pen drawings formed the basis of several painted studies [figs. 14, 15, 16] of a wealthy Venetian woman being helped out of a gondola and into a palazzo, while another person in the gondola gives a handout to the boat of beggars that has attached itself to the wealthy family’s gondola. Sometimes the wealthy woman is helped out of the gondola by a black or dark-skinned servant, at other times by a man in a top hat. Sometimes a small child hands over the alms, at other times it is a younger woman. However, the beggar is always a woman with an infant on her lap, accompanied by several other children in the boat, while their bearded father steers the boat and holds his hat in his hand in an attitude of humility. Marstrand wrote: ‘I have seen a small boat with a family of beggars on the Grand Canal. I let them attack a gondola whose passengers are about to disembark, and who gives them alms’.25

Like other Venice scenes by the artist, the beggar scene contains a number of interesting contrasts: the exquisite gondola up against the beggar’s boat; the wealthy woman in her beautiful dress compared to the beggars’ worn clothes; how the rich woman is helped to elegantly alight from the gondola while the begging mother reaches out one hand for money as the other craBeggdles her child; the city’s impressive and famous monuments as the backdrop of his mundane scene. Marstrand himself described these contrasts in his letters:

Then you step off at a bridge where a thousand servile vagabonds are eager to help one out; you proceed to step into a palace to look at Titian and Paolo Veronese, and then, once again gliding along on the great canal, a beggar family in a wretched boat comes up and keeps stride with you until you give them a quantrin; that is how that family makes a living.26

In a number of scenes he includes a monk in the stately gondola; a choice that can be read as a critical comment on the role of the Catholic Church as an institution charged with helping the poor while at the same time being an institution of great power and wealth. When painting Danish subjects, Marstrand would also often employ this contrast between rich and poor, thick and thin, young and old. As a Dane and Protestant in Catholic Venice, he was an outside observer; as an artist, he found himself ranked somewhere between the gentlefolk and the vagabonds. Marstrand was not a social-political agitator, but in his pictures he would subtly and sarcastically lambast the high and low, the clergy and the laymen alike. His critical sting is wrapped up in the velvet glove of humour.

His discreet approach becomes even more apparent in a later version of the beggar motif where the beggars have disappeared entirely from the picture: all that is left is the noble lady being helped out of her gondola. [fig. 17] For those patrons who preferred idyllic scenes over social realism, Marstrand could accommodate their wishes by omitting any elements that might be offensive to the bourgeoisie; elements they would not want hanging on their walls. Marstrand once again used the view from his terrace as background in several of the scenes; he looks either to the east to the aforementioned Santa Maria della Salute, or he looks to the west where the tower of the Basilica dei Frari can be seen in the distance.

In another variation on the beggar theme, Marstrand depicted a group of beggar monks. Marstrand’s monks are shown getting out of their boat with the outcome of their begging – and their spoils are rather good! In two sketches [figs. 18, 19], Marstrand chose to paint the gondola viewed from the side and at a slight angle. In another painted sketch [fig. 20], as well as the finished image [fig. 21], he has shifted to a different perspective, showing the gondola parallel to the edge of the image and the Santa Maria della Salute in the background. Based on the location of the Salute church on the left and the bell tower of St. Mark’s Church to the right, it is most likely that the monks have sailed to the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. This was the site of a Benedictine monastery that had been partially closed after the Venetian Republic fell to Napoleon in 1797.

Marstrand’s monks do not wear the black cowls of the Benedictine monks, but the grey-brown habit of the Franciscans. The Benedictine order were not beggar monks, while the Franciscans were. However, the Benedictine monastery gave Marstrand a strategic location with the dark monks in front of the view of the bright city in the background, the beautiful domes and spires of the city like castles in the air, raised high above a rather more down-to-earth and exploitative approach to the Christian message of charity. One may reasonably assume that with these subjects, Marstrand wanted to criticise the financial affairs of the Catholic Church or its monasteries, for during an earlier stay in Italy he had written about ‘the disgraceful power which the clergy wield here and which they abuse in the most appalling manner’.27 It is also worth noting that in the foreground of the painted studio we find a little boy on the quay while the finished painting boasts a demijohn of wine, which seems a poor fit for the supposedly ascetic lives of the beggar monks. Indeed, Marstrand’s title indicates that the monks are bringing home their ‘spoils’, suggesting that they are not poor beggars, but practically robbers. As an artist, he chose his motifs very deliberately, and he portrayed Venice on the basis of Danish and Lutheran ways and morals. Compared to his romanticised portrayals of Italian revelry from the earlier travels, his portrayal of the beggar monks is infused by a rather more critical sobriety. Outside the walls of the monasteries, where the Church invokes divine rights and powers, Marstrand pointed out that the common folk were being subjected to a very mundane form of exploitation.

The bridge from the previous scenes makes yet another appearance in a small painting of two corpulent tourists in a gondola. Holding a guidebook, presumably the widespread Baedeker,28 they sail around Venice, but like all tourists they too grow tired. The man has even fallen asleep, prompting the woman to regard him with a look that may be interpreted as one of concern – or perhaps of reproach [fig. 22]. Then as now, the presence of tourists in Venice created employment for the city’s inhabitants. Gondoliers were one example; musicians were another. St. Mark’s Square is home to the historic cafés Caffè Florian, Caffè Lavena and Caffè Quadri, all dating back to the eighteenth century, which means that they were also there when Marstrand stayed in Venice. Both Florian and Quadri have a tradition of having live music in the square in front of the café, but that particular tradition was supposedly established in the twentieth century. Even so, Marstrand’s drawing of male violinists may still depicts café musicians. [fig. 23] In their fine attire, they constitute a marked contrast to the group of wandering musicians that Marstrand drew on the other side of the same sheet. [fig. 24] Marstrand also did a painting of the musicians. [fig. 25] The drawing shows the musicians actually playing, while the painting depicts them preparing to make music. While the drawing is undated, the painting is dated 1857, i.e. three years after Marstrand returned home from Venice. In the drawing, we see the arches on the characteristic loggia of St. Mark’s Square in the background. This is to say that we are placed in the square, looking towards the buildings. In the painting, on the other hand, the buildings are viewed from a distance and in bright sunlight, meaning that we are looking at the scene from the north-facing side towards the south-facing side. The musicians are quite literally and figuratively left in the shade, while the sunnier aspect of life, once again in the figurative as well as literal sense, features women in bright dresses with wide skirts, carrying hats and umbrellas as they enjoy a leisurely walk. While the drawing saw Marstrand draw two different classes of musician, one on each side of the paper, he painted two different classes onto the canvas, one on each side of the square. As in his beggar scenes, Marstrand shows the darker aspects of beautiful Venice. The musicians of the cafés may be wearing finer clothes, but they are just as dependent on the goodwill of the wealthy tourists as the wandering minstrels.

As far as Marstrand’s relationship with the National Romantic trends in Denmark is concerned, one might say that he expressed his admiration for Venice through his choice of subject matter when creating romanticising portrayals of beautiful women, beautiful buildings and beautiful light. However, he also expressed love for his native Denmark by incorporating a critique of the southern ways, lambasting the lavish lifestyles of the lords in the palazzos with their servile attendants or the exploitation perpetrated by the Catholic Church. Marstrand’s gaze was not only tinted by his being a Protestant, but also by being a citizen of a country that had very recently abolished an absolute monarchy and introduced a constitution.

The figure painter and the landscape painter in Venice

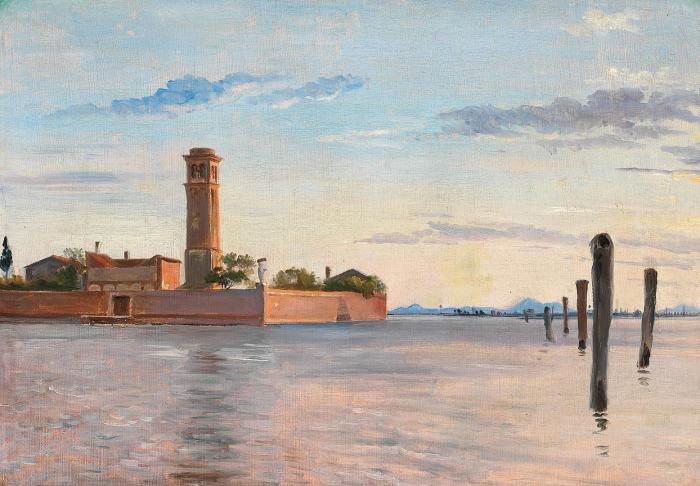

When P.C. Skovgaard and his wife Georgia stayed in Venice in May–June 1854, the two families spent quite a lot of time together, and the two painters created scenes that shared a kinship with each other, yet were also different. In a scene by evening light that Marstrand first painted without any figures as staffage [fig. 26] and, later, with a gondola with a man, woman and child [fig. 27], the Isola di San Giorgio in Alga can be seen in the background.29

Like Marstrand, Skovgaard painted scenes of the lagoon too, and he appears to have used Marstrand’s study as the basis of a painting which does not feature an Italian family, but Danish figures instead. P.C. Skovgaard incorporated himself in the picture, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and reaching out to little Poul Marstrand; in the centre we find Wilhelm Marstrand, and their wives sit with their backs turned toward us. [fig. 28]

Thus, both painters use Venice as a backdrop for various staffage figures. As if staging a play, they select scenery, props and costumes to clearly signal where you are. When, a few years later, Skovgaard painted three overdoor paintings for the politician Ditlev Gothard Monrad (1811–87), he chose Italian subjects for each piece. One is a view from Monte Pincio in Rome, the second a prospect from Naples, and the last is a view from the lagoon in Venice.30 Thus, the subjects picked out by the artists during their travels abroad could appear in their works several years after they had returned home. The sketches and studies retained their impressions for later strategic use, much to the benefit of Danish customers who could demonstrate their patriotism by purchasing Danish art, yet at the same time emphasise their sophistication by choosing Italian subjects. [fig. 29]

Marstrand may also have thought about doing an overdoor painting featuring a scene from Venice, because he too did an elongated transverse view of the city as seen from the lagoon. Here he strategically chose to include no less than three well-known edifices from Venice [fig.30]: From the right we see the Doge’s Palace with St. Mark’s Campanile, Santa Maria della Salute in the middle, and to the left the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore. On the water are gondolas and many-masted ships. Like Skovgaard’s overdoor, the foreshortened gondolas on the water act as markers that create a sense of depth in the image while also clearly placing the scene in Venice. Such devices enabled the artists to create scenes that were both easy to recognise and much-coveted, allowing the future owners to lay claim to being educated men of the world, familiar with the wonders of Venice.

Whereas Skovgaard looked out towards the lagoon for his painting, Marstrand looked from the lagoon towards the city. We see, then, that the landscape painter chose an angle where, incorporating a few boats and buildings, he creates an airy and calm composition with greater focus on nature. In contrast, the figure painter chose to have a densely packed horizon in the background and several boats in the foreground, creating a more dynamic composition focusing on the city and city life. Marstrand had rented a home for his family on the south side of the Grand Canal with a terrace facing the canal and overlooking the church of Santa Maria delle Salute, a view that, as has been mentioned before, appears in several of Marstrand’s depictions of the city.

The Skovgaards visited them here, and Skovgaard did a drawing of the view [fig. 31]. P.C. Skovgaard himself can be seen to the left, followed by the dark-haired Georgia Skovgaard, then Grethe Marstrand, and, standing on a chair to look over the edge of the terrace, the Marstrands’ young son Poul. Skovgaard also painted a picture from the terrace [fig. 32]. In the foreground are the same potted plants seen in the above drawing, in the background we see the Salute church, and on the edge of the balcony are a handful of juicy, red cherries. A few gondolas appear on the Grand Canal, but it is quite clear that for Skovgaard – unlike Marstrand – the figures are not of key importance, nor are the narrative aspects. The gondolas are just elements in a classic veduta of Venice in the style of the prospects created by Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (1697–1768) or Francesco Guardi (1712–93).

Marstrand himself also used the view from his terrace as a backdrop in several pictures. Whereas Skovgaard’s paintings are usually almost entirely devoid of figures, Marstrand took the exact opposite approach, focusing on figures and narrative in his paintings. He emphasised contrasts and highlighted folk life, even though he noted in his correspondence that such scenes were difficult to find:

Life is very monotonous; the people are not beautiful and there are no costumes here, all peculiar customs and scenes of folk life have disappeared since the Revolution, now one only sees the military, some rather paltry commoners and the most boring elegance imaginable in St. Mark’s Square . […] There is greater pleasure to be found in seeing the lines of the Alban Hills from Rome than in all the magnificent buildings of Venice. Only the fishermen and the life they lead on the beautiful sea are interesting’31

Although Marstrand himself emphasised the beauty of nature, it was not the main feature of his art. Rather, he would repeatedly return to the contrasts between magnificent buildings and squalid commoners, depicting it in two main groups of subject matter.

In two scenes from Venice painted by Skovgaard in June 1854, it is once again evident that, unlike Marstrand, Skovgaard was more interested in the city itself than in its inhabitants. [figs. 33, 34] When Marstrand painted urban motifs devoid of staffage, he only did so to prepare backgrounds for his figure paintings. For example, Marstrand’s view of the Grand Canal [fig. 35] was a study for Alighting from a Gondola in Venice [figs. 16 and 17], while his study of Palazzo Falier [fig. 36] was to be used as the background of another planned figure painting [fig. 15]. The third of Marstrand’s architectural studies [fig. 37] used to belong to Niels Skovgaard, who presumably inherited it from his father, P.C. Skovgaard, who may have received it from Marstrand as a memento of their time together in Venice: this would make it a scene without figures made and given by a figure painter to his friend, a landscape painter.

The difference between Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s choice of subjects from Venice highlights the difference between the two painters: whereas Marstrand focuses on the portrayal of characters, on figures and the narrative aspects of his lively and dynamic depictions of all walks of life in Venice, any figures are always seen at a distance in Skovgaard’s scenes. He portrays the city space, the views of the lagoon and the canals. There is a sense of calm and harmony to Skovgaard’s scenes, while those of Marstrand are more compact in composition, full of contrasts, a tongue-in-cheek irony and interaction between the characters. Marstrand’s depictions of the Venetians are partly romanticising, partly distancing: the Italians are always Other, different from the Danes, regardless of whether they are shown sailing in gondolas or begging for charity.

Farewell to Italy

Although Marstrand spent many years in Italy, his relationship with the country is pervaded by a certain ambivalence. Shortly before his departure from Venice, Marstrand wrote to Skovgaard:

We are now about to leave this place, where we have sweated and suffered […] I will probably never come here again, nor will the memory of this year do anything to draw me back, so it is perhaps all to the good that all my thoughts and yearnings now go only to my native land.32

Marstrand’s wife, Grethe, also expressed her preference for the familiar and the homelike in a letter to Georgia Skovgaard:

although I take quite inexpressible pleasure in all the grand, beautiful and magnificent things one sees and enjoys on such a journey, and perhaps will yearn for many times since, I nevertheless find that in the long term, the foreign has no good influence on me, and I feel how strongly I cling to familiar and homely tings, even if one dare not engage in comparisons’.33

On the one hand, Marstrand was enthusiastic about Italy, on the other he was critical. He put emphasis on expressing his love for his native country, and when comparing the two countries his preference would, all things being considered, reside with Denmark. Accordingly, Marstrand’s Italian subjects merit consideration in the light of the widespread discussions concerning the national in Danish art.

In Denmark there was widespread opposition to Danish artists being influenced by foreign styles during their travels, certainly if this meant they were no longer true to their Danish origins. Professor of art history at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870), argued that Danish artists should cultivate a national art and not try to emulate movements found abroad. He even went so far as to dissuade certain artists from travelling abroad so that their Danish character was not influenced by foreign art; Skovgaard was supposedly among their number.34 His influence on Danish artists – wielded partly through his position as a professor at the Academy from 1829 to his death in 1870 – cannot be ignored. However, Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s travels clearly demonstrated that travelling to (especially) Italy and studying the art there was still a widespread and widely approved part of a fully rounded education as an artist. Høyen himself also travelled quite a bit in Europe, including in the company of Marstrand and Skovgaard.35 When Høyen visited Venice during Marstrand’s stay there, the latter wrote: ‘Høyen […] is not among the blind, nor among those who view things in a hurry; he spent every day from morning ‘till night watching and was in a state of everlasting intoxication from the buildings and paintings of Venice’.36 Although Høyen was impressed by Venice’s art, Marstrand was aware of Høyen’s national zeal and how it impacted his assessment of e.g. the German collections he visited on his way home from Venice. In a letter to Skovgaard, Marstrand wrote:

Høyen […] now has the peace and quiet necessary to process the Italian impressions, which perhaps time would not allow at first back home. What is more, there are excellent collections in Berlin, and he also now has the opportunity to more thoroughly condemn the German spirit or if he still feels his strong national zeal or, which would be far dearer to me, to grow rather calmer about it all and not tar everything with the same brush.37

One senses that the artist and the art historian do not see eye to eye in their assessment of foreign art, and that Marstrand’s ‘national zeal’ was not quite as strong as Høyen’s. During his stay in Venice, Marstrand wrote:

On the whole, I personally feel that it is about limiting oneself and then expanding within those limits, because there is enough content to be found in the smallest, poorest space. – I do not think that Italy will disturb me anymore, but I am grateful for all the beauty it has taught me to see at home too.38

Marstrand’s time in Venice can be seen as a way of expanding one’s own reach within the boundaries set by the national tendencies: allowing oneself to take pleasure in working with Italian subjects while also portraying them with a mixture of criticism and affection. Tellingly, Marstrand states that his time in Italy has taught him to see the beauty at home, leaving no doubt about his patriotism. However, it is food for thought to see how he expresses great joy in portraying scenes of common people going about their business in Venice, such as the fishermen, while he did not take corresponding pleasure in studying the common folk in Denmark, even though he did try to cultivate that theme. Writing from Venice, he said: ‘I think with pleasure on the fact that every summer I will spend some months living among peasants and fishermen, and see if I can grow to love them and their labours’.39

Marstrand also painted Italian subjects while in Denmark, including several years after his return. Perhaps he did so because he dreamt of a place he missed, perhaps because such Italian scenes were in demand among his customers. In a letter from Venice, Marstrand once again wrote to Skovgaard about how his love was split between Denmark and the south:

It is true, I suppose, that one does not find beauty by searching for it, but nor can it be found everywhere; it too is governed by external conditions, and however much you love art and Denmark, you will not find the offspring of the southern sun there, and once loved, one cannot help but miss them.40

However, Marstrand’s letters also include examples of him expressing great love for Italy – and a lesser love for his native Denmark. In a letter from Marstrand to Skovgaard after the latter’s departure from Venice, he wrote:

If only we could have Titian and Poul [Paolo Veronese] before our eyes once in a while at home, yes, and all these lovely people and other delights – yet perhaps I may even succeed in arriving at a full enjoyment of the beauty of life back home, too.41

Marstrand described Skovgaard’s character in a letter to councillor Michael Kjær Raffenberg (1802–1881), who was a close friend of Marstrand, during the Skovgaards’ visit in Venice, ‘perhaps he [Skovgaard] is right to not wish to work with the Italian countryside, for I believe he is far too Danish to truly grasp it’.42

Here, Marstrand describes Skovgaard’s strategy in relation to the national trends of the time. Skovgaard only visited Italy twice and made briefer stays there than Marstrand. Hence, it is only natural that Skovgaard’s oeuvre contains fewer scenes from Italy than Marstrand’s, but as Marstrand states, Skovgaard also hesitates to engage directly with the Italian countryside, even while staying in Italy. Marstrand believes that the reason is that Skovgaard is far too Danish, but Skovgaard may also have deliberately chosen not to paint Italian scenes in order to avoid being perceived as a painter who had succumbed to foreign influences.

In the time after Marstrand and Skovgaard’s travels in the 1850s, there seems to be yet another shift towards the national in Denmark. The nation’s defeat in the Second Schleswig War in 1864 certainly did nothing to alleviate the aversion to all things foreign. Although Danish artists still travelled, the earlier tradition of staying away for several years was waning. Now, artists were no longer supposed to learn how to paint by studying Italian artists like Titian and Veronese; increasingly – and as a result of several reforms at the Academy – they were expected to do so during their training at home in Copenhagen. During his last trip to Italy in 1869, in the company of Skovgaard, Marstrand reflected on how the tradition spending many years abroad, one which he himself had practiced, might be coming to an end:

Settling in Rome for long periods of time, four or five years, is now a thing of the past, and perhaps it is no longer necessary; now perhaps each country is better able to educate its own artists, which would at least be more natural.43

Nor did Skovgaard express a need to be abroad more often or for longer stretches at a time; he was happy to be able to draw inspiration from outside, but he was also happy with the familiar and homelike. During his last trip to Italy in 1869, he wrote home to his family:

I have most certainly benefited greatly from the journey so far; I enjoy these incomparable works of art even better than the first time I saw them, indeed, I will now carry that joy for the rest of my life, and do not think I will long to come here again; from this point on I will settle down at home and rejoice in what is beautiful there.44

We see, then, that the growing National Romantic tendencies in Denmark after 1850, given further impetus by the events of 1864, reduced Italy’s importance as a destination for the edification of Danish artists.45 This held true in actual practice as well as in the reception of Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s late pictures from Italy. In the older and existing literature, a scepticism was expressed towards the Italian scenes created by the Danish Golden Age painters, a critical outlook which continued into the twentieth century. Accordingly, such reservations towards all things foreign and Italian in favour of Danish subject matter can also be found in Karl Madsen’s monograph on Marstrand from 1905, in which he wrote:

Oh, how dearly we would have liked to have gone without several of the – at times somewhat vapid or dull – recollected scenes from Italy that Marstrand continued to paint, in order that we might have had more scenes of Copenhagen from his hand. For, notwithstanding how he quite rightly regarded man as the essential subject and costumes as insignificant, Italy, – and especially the Italy he has portrayed, will always be somewhat foreign and distant to us, our interest in it unavoidably rather cooler and less intense than our interest in the city that used to belong to our fathers and is now ours.46

Theodor Oppermann presented a similar argument in his monograph about Marstrand, stating that an artist could only find the right conditions for their art in their own homeland.47

P.C. Skovgaard’s works from his Venetian sojourn have been largely ignored in the literature about Skovgaard as a painter, which has mainly focused on his Danish landscape paintings – as is evident from his widely used moniker ‘the painter of the Danish beech forest’. Not until the 2148 century have the Venetian scenes become a subject of renewed attention.49

The discussion concerning the national in art reached its culmination a few years after Marstrand’s and Skovgaard’s deaths (in 1873 and 1875, respectively) with the critique of the Danish exhibition at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878, which included works by both artists. Here, their paintings were described as ‘bourgeois, naïve, provincial, overly well-scrubbed, neat and consistently Sunday School-like’.50

The Danish art scene did not agree with the French critique, as is clearly evident from the fact that a sculpture of Marstrand was erected in front of the National Gallery of Denmark in 1901. And as the art historian Julius Lange (1838–96) stated about the critique of Skovgaard’s works at the Exposition Universelle:

To overlook or underestimate the great and good things that have been granted to us by an artist, even if his direction is not currently high on the agenda in the wider world, would be poor housekeeping; the wheels turn very fast in the big world. Multa renascentur: – -.51

Lange concludes by quoting Horace: Multa renascentur, quæ jam cecidere, cadentque / Qua nunc sunt in honore, vocabula, si volet usus: ‘Many terms that have fallen out of use shall be born again, and those shall fall that are now in repute, if Usage so will it’. Perhaps the reputations of Marstrand and Skovgaard will change too, ushering in a reappraisal of their Venice works. Perhaps one day, audiences will once again prefer Marstrand’s fully finished paintings to his studies. Perhaps the sculpture of Marstrand will one day be reinstated at the monumental stairs leading up to the National Gallery of Denmark. Multa renascentur….

Bibliography

Danish Golden Age – World-class art between disasters, Copenhagen: National Gallery of Denmark, 2019.

Guld. Skatte fra den danske guldalder. Systime, 2013.

Karina Lykke Grand, Nye optikker på dansk guldalder. Rejsebilleder og det fotografiske blik. PhD dissertation, Department of Art History, Aarhus University,, 2007.

Karina Lykke Grand, Dansk guldalder. Rejsebilleder, Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2012.

Peter Michael Hornung: Ny Dansk Kunsthistorie. Vol. 4: Realisme. Forlaget Palle Fogtdal, Copenhagen 1993.

Kunstforeningens Marstrand-udstilling i Udstillingsbygningen ved Charlottenborg, Charlottenborg 1898.

Julius Lange, ‘Nogle af de døde. I. V.N. Marstrand. Tale ved Akadmiets Aarshøjtid den 31. Marts 1873 ’, and ‘Skovgaards Billeder paa Verdensudstillingen i Paris 1878’ in Billedkunst. Skildringer og Studier fra Hjemmet og Udlandet, Copenhagen: P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1884, 400-409 and 450-458.

Julius Lange, ‘Marstrand. Holberg. Per Degn. (1884)’ in Udvalgte Skrifter af Julius Lange, published by Georg Brandes and P. Købke, volume 1, Copenhagen: Det Nordiske Forlag, 1900.

Karl Madsen, Wilhelm Marstrand 1810-1873, Copenhagen: Kunstforeningen, 1905.

Otto Marstrand: Maleren Wilhelm Marstrand, Copenhagen: Thaning & Appel, 2003.

Vilhelm Marstrand. Breve og Uddrag af Breve fra denne Kunstner. Samlede og ledsagede med nogle indledende Ord af Etatsraad Raffenberg. Copenhagen 1880.

Wilhelm Marstrand: Tegninger fra Italien, Teknisk Forlag, year unknown

Ferdinand Meldahl and Peter Johansen, Det kongelige Akademi for de skjønne Kunster 1700-1904, Kbh.: H. Hagerups Boghandel, 1904.

Kasper Monrad, Hverdagsbilleder. Dansk Guldalder – kunstnerne og deres vilkår, Copenhagen: Christian Ejlers Forlag, 1989.

Hans Edvard Nørregård-Nielsen, Dengang i Italien. H.C. Andersen og guldaldermalerne. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 2005.

Gertrud Oelsner and Karina Lykke Grand (eds.), P.C. Skovgaard. Dansk guldalder revurderet. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2010.

Theodor Oppermann: Wilhelm Marstrand. Hans Kunst og Liv, København: G.E.C. Gads Forlag, 1920.

Tue Ritzau and Karen Ascani, Rom er et fortryllet bur. Den gyldne epoke for skandinaviske kunstnere i Rom, Copenhagen: Forlaget Rhodos, 1982.

Sally Schlosser Schmidt, ‘National art vs. national art. Wilhelm Marstrand’s and P.C. Skovgaard’s views on national art around 1854’, in Perspective Journal, September 2020: https://perspectivejournal.dk/en/national-art-vs-national-art-wilhelm-marstrands-and-pc-skovgaards-views-national-art-around-1854

Gitte Valentiner: Nivaagaard viser Marstrand, Nivå: Nivaagaards Malerisamling, 1992.

Gitte Valentiner: Wilhelm Marstrand. Scenebilleder. En monografi af Gitte Valentiner, Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1992.