Summary

Peter Christian Skovgaard is primarily known as a landscape painter. But he was also a draughtsman. This article explores the role of drawing in Skovgaard’s art and life – why did he draw, what did he draw, and to what uses did he put his drawings? The intention is to demonstrate how Skovgaard’s drawings can help elucidate the role of drawings in Danish Golden Age art while adding greater nuance to the general perception of Skovgaard as exclusively a landscape painter.

Article

According to Joakim Frederik Skovgaard (1856–1933), the influential Danish art historian Niels Lauritz Høyen (1798–1870) counselled his father, Peter Christian Thamsen Skovgaard (1817–1875) against working with decorative painting. Høyen would apparently prefer to see Skovgaard devote himself to landscape painting.1 Indeed, art history tends to mostly refer to Skovgaard as the landscape painter whose depictions of the Danish countryside helped convey a ‘special sense of national identity’.2 He did so in an era of growing national awareness in the wake of momentous events such as the British bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807, a currency reform that placed the nation in dire financial straits in 1813, and the loss of Norway in 1814. While none of these occurrences were conducive to national confidence, they did prompt a search for elements that could elicit pride and a sense of community among the Danish people. With his frequently monumental scenes of beech forests, coastlines and woodland lakes, Skovgaard responded directly to a need evident at the time, thereby earning a place in art history as a representative of so-called National-Romantic landscape painting which met this need for establishing a firm identity.

The general perception of Skovgaard’s art and his position within Danish art history has to a great extent been shaped and governed by the large Skovgaard exhibition at Charlottenborg in 1917. Skovgaard’s sons, Joakim and Niels Skovgaard (1858–1938), joined art historian Karl Madsen (1855–1938) in arranging this comprehensive exhibition, featuring more than 800 works, to celebrate the centenary of the birth of the old Skovgaard. The show offered a unique opportunity to study and compare much of Skovgaard’s production, from small-scale sketches to monumental oils. Drawings were heavily featured in the exhibition, accounting for 337 out of the total of 827 works on display, but their importance and qualities in relation to the paintings has been a matter of contention up through history. At the Charlottenborg exhibition, Skovgaard’s eldest son, Joakim, met one of ‘the great composers of the age’,3 who spoke about his visit to the exhibition with great enthusiasm. He supposedly said:

The studies and sketches went straight to one’s heart as if they were flowers, he declared, but not so the large paintings, they did not quite appeal, but then he told himself that ‘surely I am at fault for failing to properly appreciate them, after all Skovgaard would have had a purpose in mind when painting them like this’. On his second visit he set out to immerse himself in them, and that helped. As a musician, he was able to take pleasure in the ways in which Father had arranged the volumes, grouped them, ordered and balanced them in order to bring forth the totality, the great harmony. Yes, that is how it is, the studies are the first to jump out at you, it is like walking in a woodland meadow picking flowers, darting joyfully from one to the next, forgetting the large trees. Let me pick yet another one before I raise my eyes.4

This is to say that the composer was initially struck more by the studies than by anything else. It would appear that the so-called ‘big pictures’ required a little more processing before he became convinced of their qualities. Art historian Henrik Bramsen (1908–2002) was far more clear-cut in his opinions twenty years later when he looked back upon Skovgaard’s body of work, stating that the main emphasis of Skovgaard’s oeuvre was undoubtedly ‘[…] the big pictures […]’.5 The aforementioned Karl Madsen was more in line with the composer’s view, believing that Skovgaard was ‘[…] of far more surpassing excellence […]’6 in his studies, which included painted as well as drawn studies, as is evident from the exhibition catalogue.7 Joakim held yet another view, making the following statement in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition : ‘[…] best of all, I believe, are his pen drawings with their broad lines, sometimes even drawn using reed pens or brushes, India ink or light watercolours when he is in particularly fine fettle’.8 This is to say that his son believed Skovgaard’s drawings to be the best of all his work.

Drawing was an integral part of the training provided at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts where Skovgaard studied.9 As is accounted for in Jesper Svenningsen’s article ‘For pleasure and for prizes. Danish plein-air painting of the 1820s’,10 one of the new departures of this era was the fact that artists would leave their studios in order to cultivate ‘the art of landscape’ on site, not just in their studios. Of course, this method served to bolster the importance of pencil and sketchbook as important tools of the trade, for the artist did not yet practice actual plein-air painting on large canvases.11 Recent research into Skovgaard’s work, such as the most recent book published on the subject, P.C. Skovgaard. Dansk guldalder revurderet from 2010,12 also confirms that he worked with drawing. However, little emphasis is placed on the methods and techniques he used, on the hows and the whys; rather, such studies tend to focus on the subject matter that attracted him.

When seeking to understand the work of any artist – how and why he became an artist, grew creatively and contributed to art history – it is always a good idea to consider how various art historians have interpreted his work through the years, accentuating some aspects over others. The historian Johannes Steenstrup (1844–1935) believed that historians should seek to consider life in all its variety and diversity, not focus exclusively on individual elements and utterances. Only by fully embracing diversity is it possible to appreciate ‘[…] how the great flow affects the individual and how the individual affects the totality’.13 It goes without saying that carrying out such an all-encompassing analysis of Skovgaard’s life and work is a mammoth task. Particularly given that Skovgaard’s total body of work is comprehensive, numbering more than 900 works on canvas and paper in Danish museums alone. To this we must add an unknown number of works in private ownership and in museums abroad. Nevertheless, I find myself attracted to using a Steenstrupian perspective as the framework for exploring how Skovgaard’s drawings can contribute to our perception of him as an artist: why did he draw, what did he draw, and what did he use his drawings for?

His drawings can differ greatly, taking the form of sketches, drafts, compositions and more fully finished works. They are done using a range of different techniques such as pencil, India ink, ink, washes and watercolour, sometimes combining several of these media. This article considers a small, but varied selection from Skovgaard’s very comprehensive production of drawings, right from his earliest childhood drawings from the 1820s to his final pieces from the 1870s, aiming for wide-ranging insight into Skovgaard’s use of drawing.

A gifted child and the myth of the artist

Skovgaard was among those artists who demonstrated their artistic flair from a very early age. According to his children, Joakim, Niels and Susette, he had – at the tender age of four – impressed large audiences with his drawing skills in connection with a harvest festival at Fredbogård near Græsted, where Skovgaard’s family lived. Susette describes the incident in these terms:

…farmhands and milkmaids, farmers and their wives were tripping the light fantastic while tables and benches stood arrayed along the walls. Young Peter had crept up to those tables, looking at the company through his young eyes, so keenly honed for observation. He found a piece of chalk, either on the table or in his own small-boy’s pockets, and drew what he saw directly onto the table; I envision an old table, painted red. Suddenly a woman stood behind him, noticing what he was doing – and she clasped her hands and cried: ‘Upon my word – there’s the crippled cowherd – as plain as day!’ And then they all flocked to see, laughing and admiring his work.14

This is to say that Skovgaard was much admired for his ability right from an early age. At the age of 14, he was granted a scholarship to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, embarking on a career as an artist. Such tales are familiar territory, for of course Skovgaard was not the first artist to demonstrate his talent at an early age.15 In a wider art historical perspective, this narrative of the particularly gifted artist can be traced all the way back to the Italian architect, painter and artist Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) and his seminal 1568 book Le vite dei più eccelenti pittori, scultori e archtitettori,16 which has since formed the role model of much art history writing. Known in English as The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, the book consists of a series of artist biographies in which Vasari incorporates many details about the artists’ personalities, childhood and family life.17 The results offer vivid and occasionally quite burlesque impressions of the artists, but they also present certain problems in terms of source checking, verification and critique insofar as the author makes extensive use of the phrase ‘scrivono alcuni’, which may best be translated as ‘some say/write’. He does not address the question of where his knowledge and examples come from.18 They are anecdotal, not firmly established data with specific, identifiable sources.

Historian Niels Kayser Nielsen warns against anecdotes: they are not the most reliable of sources. He describes anecdotes as complex entities, poised somewhere between what he terms authenticity, meaning what actually took place in its original, unprocessed form, and chronology, the system we can use to record events and which includes the division and ordering of time and incidents nto regular units. The tenuous position of anecdotes is something of a weak spot in what Kayser Nielsen calls ‘the utilisation of memory’ – when did these things happen, exactly? And how?19 According to Kayser Nielsen, we should – when considering history – endeavour to co-ordinate the various narrative fragments and tie them all together in a coherent whole. While carrying out this work, we should, of course, be aware of what sources we are using and why. Susette’s story about the incident at Fredbogård is also anecdotal: for obvious reasons, neither she nor her brothers, who have told more or less the same story in other contexts, could have witnessed the events themselves. The story was passed on to them by someone else, but we do not know who. In an ideal world, we would have been able to form our own opinions by actually viewing the table with the drawings mentioned in the story. Or we would have been able to read an eyewitness account. But given that the table was not preserved nor any eye witness accounts written down, we are stuck with the next best thing – the written sources available to us, with all the caveats that they entail.

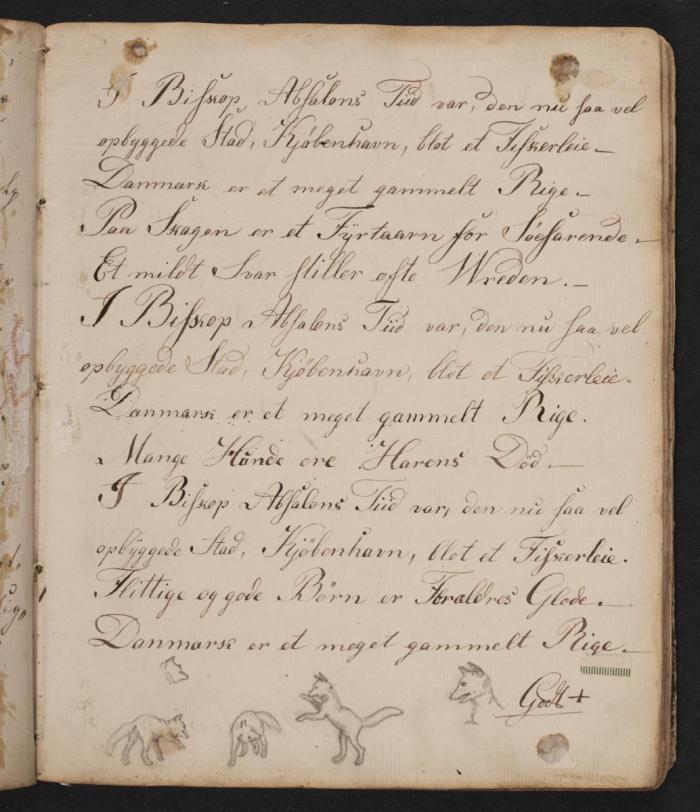

The actual surviving childhood drawings done by Skovgaard may be more useful for our purposes: we are fortunate in that several sketchbooks of his childhood drawings survive, as does an exercise book from his 1820s childhood. The drawings were done at his home in Vejby in Northern Zealand, where he lived from he was six until he was fourteen. Skovgaard’s mother, Cathrine Elisabeth Skovgaard née Aggersborg (1795–1851) had received drawing lessons from the flower painter Fritzsch – a common enough pursuit at the time among families eager to give their daughters a good education.20 Her interest in drawing may well have influenced her son, who was reportedly also encouraged to draw by his teacher, Niels Jensen (1781–1865). Jensen gave Skovgaard a book for that very purpose, presumably prompted by having seen how Skovgaard devoted more of his school exercise books to drawing than to writing and doing his exercises.21 We do not know whether the exercise book now in the ownership of the Skovgaard Museum is indeed the exact same one that Skovgaard received from Jensen, but it is quite likely. The book bears Skovgaard’s name and the date 4 April 1828 on the front page. In view of the date, the book must date from Skovgaard’s 11th birthday. Numbering 89 pages in total, the first part of the book contains brief texts written by Skovgaard in careful copperplate, annotated with the teacher’s assessments: ‘Good’, ‘Very good’ etc. However, at some point the pages undergo a change: drawings of animals, people, houses and flowers that are not intended as illustrations to the text spread out across entire pages or swirl around the texts. [fig. 1]

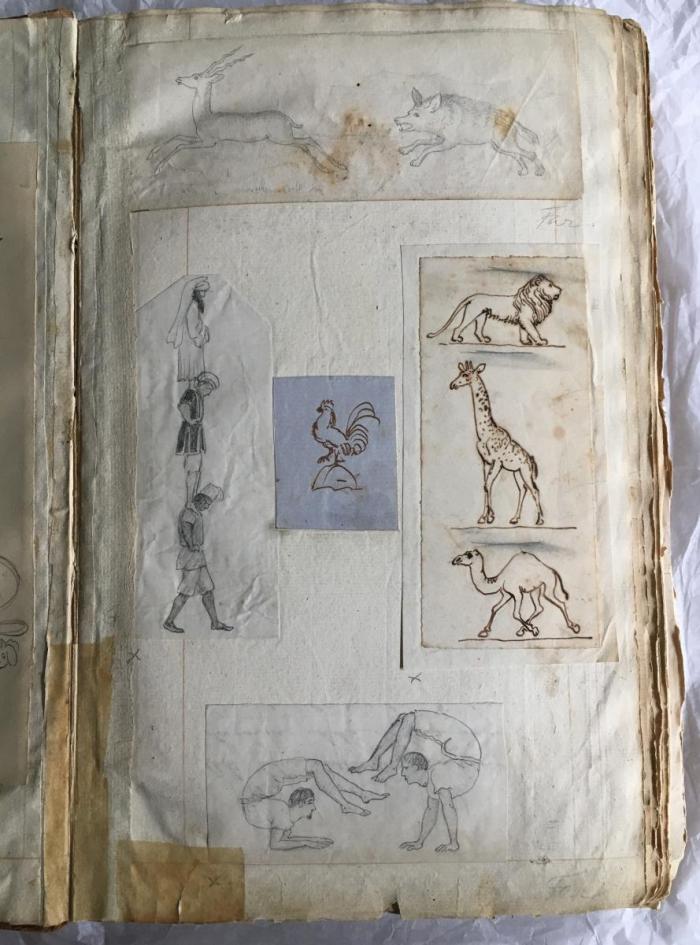

ARoS Aarhus Art Museum owns two sketchbooks from the late 1820s or early 1830s; these too are full of studies of plants, animals and houses, landscapes and natural scenery as well as drawings of knights and castles. Skovgaard also drew full-length portraits of noblemen; their appearance suggests that they were drawn after prints. While these drawings can hardly be said to possess great artistic merit, they do serve to demonstrate the abilities that attracted such attention when Skovgaard was just a child. The drawings depict fairy-tale worlds of wonder as one would expect from a child, but even so they offer unique insight into the themes that occupied him in his very young years. Later in life, such individual drawings and fairy-tale worlds would bring joy to Skovgaard’s own children, for whom he drew small drawings featuring subjects he never took up on canvas. In a 1934 article, Susette describes how ‘when anything unknown to us that came up in conversation, Father would draw it for us’,22 and she collected several of these drawings in a scrapbook. [fig. 2] The drawings show how Skovgaard used quite a crisp, clean style to create compositions that did not have too many details, but presented a clear narrative. The book includes illustrations for the children’s song ‘I skoven skulle være gilde’ about a party among the animals of the forest as well as depictions of circus acts, equilibrists, a Russian troika and numerous drawings of animals, several of them quite exotic. These drawings were not intended to impress a public audience: their sole purpose was to instruct and guide the children and stir their imaginations – just as he himself did as a child.

From peasant lad to academy student – a gulf bridged by drawing

The fact that Skovgaard had talent was one thing, but the impressive efforts undertaken by his schoolmaster, Niels Jensen, were every bit as important in launching his career. Jensen devoted great attention to having Skovgaard rise above his social background to embark on an art education at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Jensen’s connections made him well suited for the task.23 He was a colleague of Hans Jensen Visby (1777–1870), who happened to be the father-in-law of the academy-trained flower painter Johan Laurentz Jensen (1800-1856), and the three men all concurred that having the young Skovgaard attend the academy would be a good idea. The men were entirely aware of the financial challenges this would entail for Skovgaard’s parents: the young Skovgaard would require clothes and money for art supplies, which he would have to pay for himself during his first years of study. However, given that his mother scraped only a frugal living selling groceries to the peasants and fishermen of Vejby, and that his father had set out for Copenhagen several years before in order to become a police officer, thereby largely writing himself out of Skovgaard’s life, it would be necessary to raise a bit of money. Fortunately, Skovgaard’s mother was held in high regard locally, so the money required was soon raised when the three Jensens arranged a collection drive in the Vejby area. The collection was launched by a letter addressed to ‘Benefactors of the shire of Holbo’, outlining the circumstances of this young boy whose artistic ability was unmistakable. Dated 12 October 1831, the letter went:

Mrs Skovgaard in Veiby has a son, who displayed a very keen interest in drawing and painting from a very early age, and who has shown an unusual aptitude for the craft. The samples included here will certainly testify to the veracity of this claim, particularly when bearing in mind that they were done solely on the basis of what little instruction has been available to him in Veiby. Upon having the boy brought to his attention, the flower painter Jensen has recently given the boy a number of excellent patterns from which to draw and encouraged him to apply for admission at the Royal Academy of Painting in Copenhagen. This has now been done; the boy has been granted a scholarship for free tuition at the academy, and he will initially be housed and fed by relatives in Copenhagen.

However, these relatives live very modestly and cannot provide the boy with everything, and as will be known to you, his mother and father have even less to spare. Thus, support is needed to keep the boy in clothes and in the required art supplies, which students are required to provide themselves, and according to Mr Jensen such support will be required for the first three to four years of his time at the academy. Securing such support is the intention behind this invitation.24

Carrying this letter in his pocket, Jensen Visby saddled up his horse and travelled the length and breadth of the area to share the message. He succeeded in raising the necessary funds, enabling Skovgaard to move from North Zealand in 1831, just after his confirmation. The young Skovgaard moved in with an uncle in Copenhagen, Hans Christian Aggersborg (1812–1895), to commence his studies at the art academy.25 In this way, Skovgaard’s drawings laid down the foundations that would determine the entire course of his life.

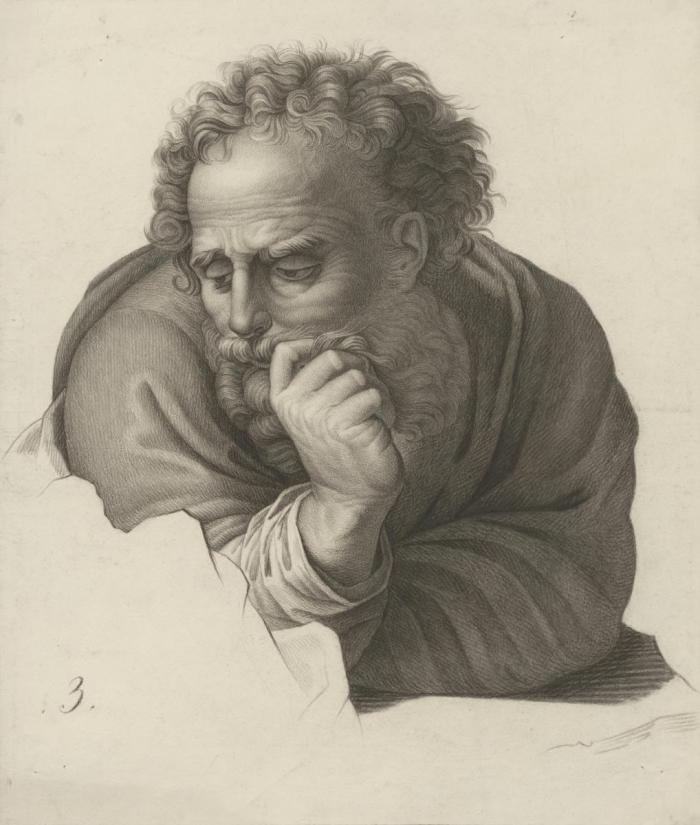

At the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Skovgaard would complete a course of training that closely resembled the curriculum followed at academies throughout Europe for centuries. The art academies of the age had their roots in the Renaissance academies of sixteenth-century Italy where drawing was a main element of the teaching and a prerequisite for all other disciplines.26 Specifically, this meant that Skovgaard would first copy drawings and prints made by other artists and then go on to draw plaster casts and attend life classes.27 For example, he was tasked with drawing the head of an apostle after Raphael and to draw boys and men in various poses, partly from plaster casts, partly after live models [fig. 3]. The results were typical academic pencil drawings done by means of very fine, thin lines and hatchings. In the drawing of the head of an apostle we see how he worked with effects of light and shadow in the draperies of the robes.

The kind of instruction that Skovgaard encountered at the academy was based on the idea that the artist would be better able to understand and appreciate antiquity when he became familiar with the human body in its ideal form from studying the classics and live models. Hence, the pupils were tasked with copying role models of classical art, which was regarded as ‘essential’ or ‘true’, whereas studies of nature were regarded as less crucial for the craft.28 Later in life, however, Skovgaard supposedly said that while he accepted the copying as useful exercises, he believed that one should essentially be allowed to draw whatever one happened to want to draw.29

Skovgaard studied art during a period where history painting was gradually losing its dominant position as a genre. It went without saying that in order to be able to depict historical, mythological and biblical scenes, artists were required to have reasonable mastery of the portrayal of the human body and its proportions. However, like many other artists at the time, Skovgaard ventured out into nature in order to cultivate the art of landscape painting. This gave him the opportunity to stand directly in front of his chosen subject matter, capturing details and recording colours for subsequent use in larger paintings. In other words, Skovgaard trained at a time when taking your sketchbook and small canvases out into nature was a must. The fact that his teacher, professor Lund, supposedly impressed upon him the need to ‘draw first, then paint´,30 clearly demonstrates that drawing was the fundamental method out of which Skovgaard’s entire artistic endeavours grew.

From paper to canvas

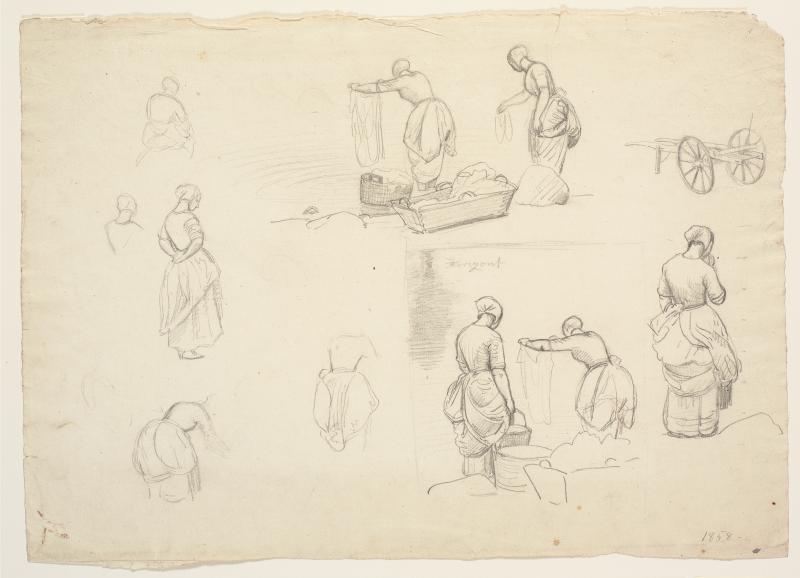

In 1858, in mid-career, Skovgaard did a drawing featuring studies of women with their backs turned on the spectator. [fig. 4] The figures were subsequently used in two paintings, one bearing the long title Quiet summer evening at a lake in the forest. Young women are washing clothes in Bondedammen in Hellebæk, while the other is called Bleaching Linen in a Clearing. [figs. 5 and 6] The drawings and paintings are excellent examples of how Lund’s dictum was reflected in Skovgaard’s specific approach. The preparatory drawings for these paintings show how he used his drawn studies as directly as possible in his paintings.

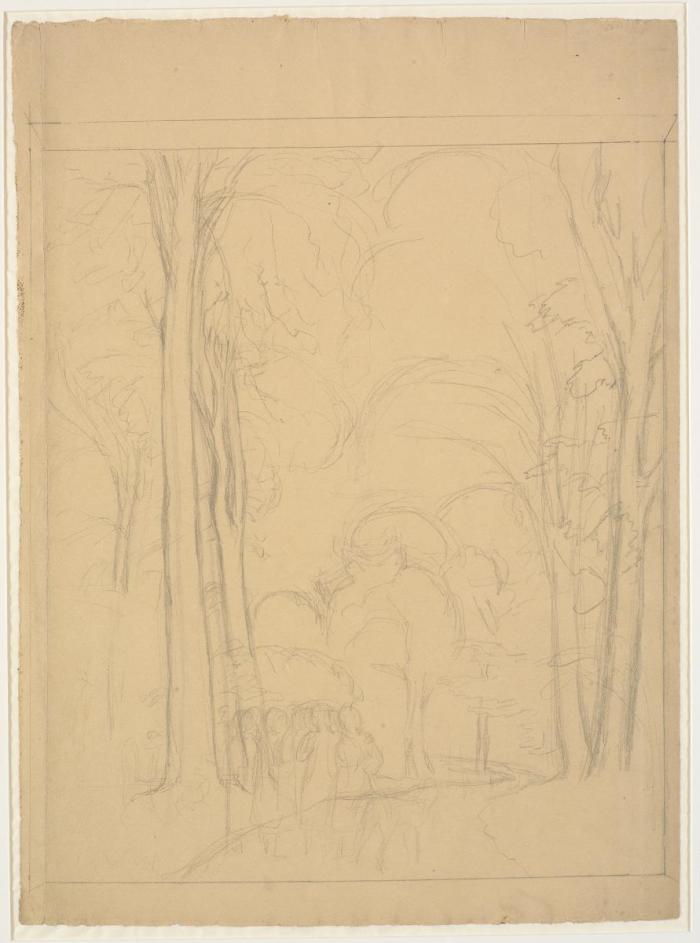

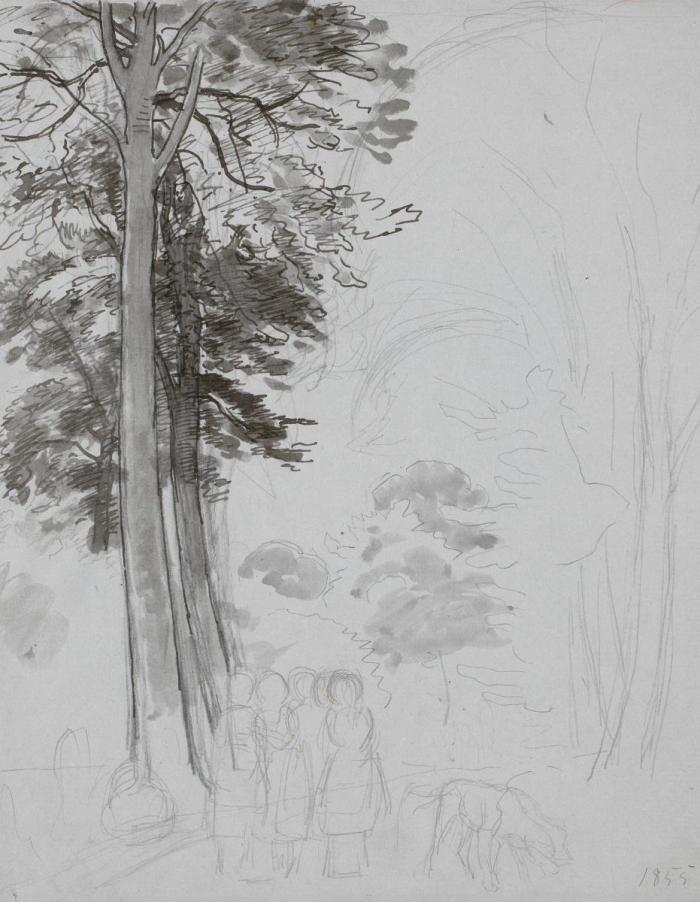

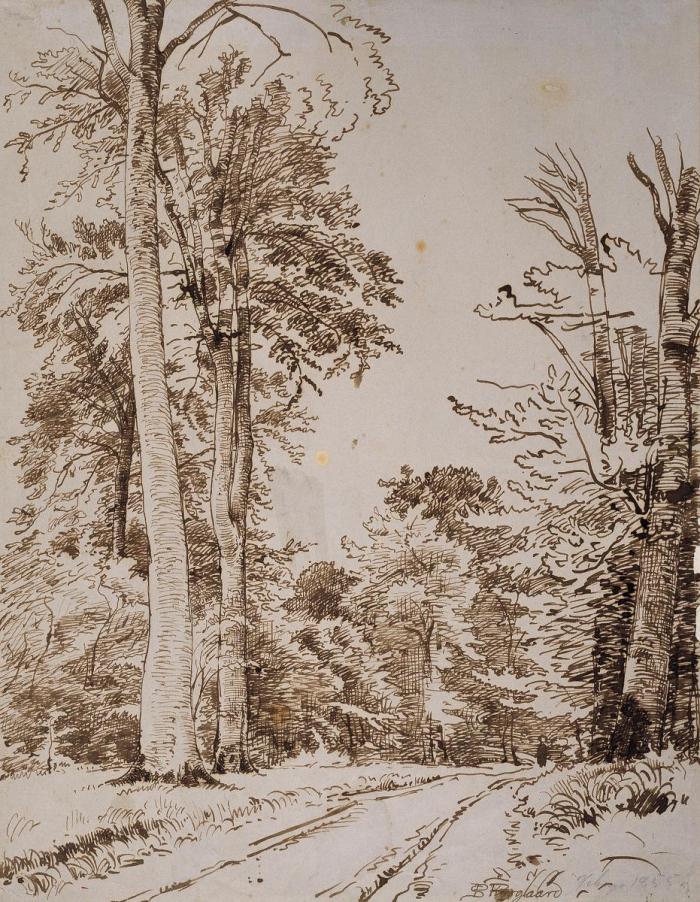

One drawing was rarely enough for Skovgaard when painting his final pictures. For example, the painting A Beech Wood in May near Iselingen Manor, Zealand from 1854 [fig. 7] required numerous drawn studies: the drawings were used almost like pieces of a puzzle, combined to form a larger painting. In this particular work, Skovgaard approached the woods as a setting for a family portrait, constructing his scene on the basis of a pathway winding its way through the upright beeches of the forest, reaching up towards the heavens. In one of the drawings, we can make out five figures and a dog looking inwards into the picture. [fig. 8] The faces, clothes and landscapes are rendered with few, if any details. Everything is rapidly and sketchily outlined, the main purpose being to create a sense of how the figures might be positioned in relation to each other. A very different effect is achieved in another drawing where Skovgaard uses India ink, grey ink and washes to depict the trees in the left-hand side of the picture, thereby creating a greater sense of depth. [fig. 9] The group has dwindled from five figures to four, and the dog’s attention has been directed elsewhere: it now looks down into the grass. A third drawing sees the woods themselves command Skovgaard’s full attention. The trees are drawn in bold India ink, with light and shadow rendered by means of hatchings of varying degrees of intensity. A human figure can be glimpsed further down the pathway. [fig. 10]

The artist also subjected the figures to careful scrutiny before making them part of the final painting. They were initially portrayed as individuals before being arranged in a group. One of the drawings show the two girls that appear in the foreground of the final painting. [fig. 11] One girl has her left arm around the other while cupping her own mouth with her right hand as if about to whisper a secret. At the top of the sheet Skovgaard did a more detailed study of the head of one of the girls. A corresponding composition appears in a drawing featuring studies of the group of children seen in the left-hand side of the scene. [fig. 12] The drawing shows two girls, one of them with her back turned against the spectator, the other facing us. A study of the latter girl’s face appears in the top right-hand corner. At the bottom is a study of a boy with his hands in his pockets. To the left sits a girl with her back turned on the spectator; in the finished painting she is part of the group that includes the girls at the top of the sheet.

Skovgaard also drew smaller studies of plants, including the common dock appearing in the foreground of the final painting. The execution of drawings such as this emphasises the natural state of the plant and its characteristic outline. [fig. 13]

Looking at drawings such as these takes us deep into the artist’s working process, showing us how his ideas about his chosen subject matter take shape. The changes he makes are small, but they nevertheless show how the finished painting is the result of several different studies and observations. The drawings can be described as building blocks that Skovgaard used to strike the right balance between the various elements included in the final scene.

The personal landscape

It is hardly surprising to find a large quantity of landscape scenes among Skovgaard’s drawings. They emerge in great numbers in the 1840s as he entered his final years of study at the academy and was called upon to find his own voice and style. Finnish art historian Janne Gallen-Kallela-Sirén believes that landscape pictures from the period during which Skovgaard was active were by definition political, serving to depict the nation in a particular and positive light. In Denmark, the range of events that befell the country in the beginning of the century, followed by the First Schleswig War in 1848-1850 and Denmark’s total defeat in the Second Schleswig War in 1864, have been pointed out as reasons for a growing awareness of national identity among the people of Denmark; sentiments that were then in turn reflected in the artists’ pictures. They do not depict war and misery, but beautiful, poetic and harmonious landscapes. However, according to Gallen-Kallela-Sirén such one-dimensional readings of this kind of imagery are by no means adequate. He states that:

Generally speaking, the cultural embodiments of this awakening and of Nordic nationalisms as such have one definite tendency in common: within all kinds of artistic activity, national identity was not defined by grand monuments and important figures, but by the local populace and their intimate, spiritual connection to nature and their immediate surroundings.31

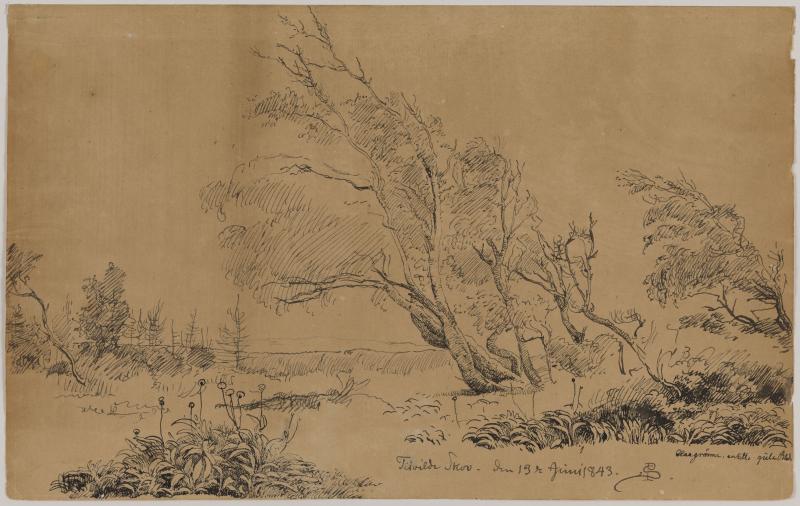

This is to say that the artists’ choice of subject matter is also, or perhaps precisely, the result of a fascination with landscape in itself. The fact that Skovgaard depicted images from e.g. his native Tisvilde is no random occurrence. Having grown up in Tisvilde, he knew the place and had a personal connection with it, prompting him to return to this location on numerous occasions even though he spent his entire adult life living in Copenhagen. Skovgaard obligingly dated his smaller pictures with great precision, giving us a reasonably clear picture of where he was and when. This is also true of his drawings, effectively making them visual diary entries. The creation of Skovgaard’s final degree work, i.e. the piece created for his academy graduation, offers an excellent example: on a journey undertaken in 1843, often referred to as ‘The Summer Journey’ (Sommerrejsen), he found the subject that would, two years later, become his graduation piece: View from the Outskirts of Tisvilde Forest.32 [fig. 14] A sketchbook dated 13 June 1843 tells us that Skovgaard sat somewhere on the outskirts of the area known as Tisvilde Hegn, [fig. 15] using a pencil to outline a gnarled, windswept birch and parts of the flora that makes up the middle distance of the finished picture. The ground with all its plants and conifers has been outlined in cross-hatching. The foreground features detailed plant studies and boulders, while flat fields peter out into the horizon at the back to be interrupted by another stretch of woodland in the distance. Grey clouds give the sky a dynamic, looming, almost threatening feel, making it difficult to ascertain whether a storm is coming or heading away. The works on paper are simultaneously gentler and more dramatic than the final painting, an effect caused by the use of pencil, pen, India ink and watercolour. [fig. 16] The artist’s son Joakim has described the painting and a preliminary study for the work in these terms:

“View from the Outskirts of Tisvilde Forest on a Windy Day”, exhibited in 1845, when Father was 28, […] In the small study for the painting the wind blusters along carrying even more sand, and the silvery hues falling upon the shrub-covered crust of earth are even lovelier, but the radiance of a study, which one can take in one’s hand and carry to a window, gazing upon it as a jewel, is one thing. What works well in a painting is quite another matter. In this painting, the loveliness has been translated into a wall, one might say; the subject and its treatment are fit for a wall made of stern stuff.33

In this quote, Joakim describes the coloured drawing as a ‘jewel’ with a distinctive ‘silvery hue’, noting that the wind is more clearly visible in the drawing than in the painting. The artist has utilised the visibility of the contours of the pen beneath the watercolour to accentuate how blades of grass, leaves and branches bend in the wind. In the painting, the vibrant, dynamic movement found in the lower part of the drawing is less evident; its sense of movement relies to a great extent on the clouds drifting across the sky and the windswept trees in the middle. The two examples demonstrate that when painting, Skovgaard had to give up a number of interesting effects that only drawing allowed him to create. They disappeared in the oils.

From the great to the small

Painting landscapes required a well-honed gift for oscillating between totalities and details. Skovgaard had the ability to study and record the tiniest aspects of nature with a wealth of detail that is rarely seen in his paintings. Several of his drawings are painstaking botanical studies of flowers and plants such as oak leaves, docks, sorrels, thistles, chestnuts and various types of field and meadow flowers. Skovgaard also drew forest floors, flowers and rocks, thereby learning how to ‘learn nature by heart’.34 His close friend Johan Thomas Lundbye (1818-1848) believed that this ability was Skovgaard’s greatest asset:

What Skovgaard depicts best of all and has immersed himself in with great love is plant life, from the greatest tree to delicate blades of grass. He is at home in woodlands; true and natural, he depicts the character of our forests, and I know of no other among our painters who is his equal in this regard.35

When Skovgaard came to teach later in life, it was incumbent on him to pass on this sense of what a keen focus on verisimilitude might contribute to the artist’s understanding of a given subject. According to Lundbye, his students did not always share his enthusiasm for the method, but wondered – as he himself had once done – about the need for the exercises with which Skovgaard ‘tried his students’ patience’.36However, this particular exercise does seem to reflect Skovgaard’s approach to his work.

A carefully worked-out study could also be used in other contexts. Several of them were eminently suited for decorative and educational purposes, and many were translated into embroidery patterns. Of course, this required some processing of the drawings: they had to be simplified, yet still appear naturalistic. Drawings intended for such use were purged of all inessentials such as shadow effects and unnecessary colours and volumes. The contours must be crisp and clear in order to see how they might work as decorative elements on cushions, furniture, etc.37 Unsurprisingly, the main themes were plants, flowers and animals. Skovgaard would then attend to the task of ensuring that a swallow did not flow out across the seat or a deer have its legs bisected by creases forming in the cushion, but as Joakim asserted, the drawings were ‘excellent, and one does not sit down on drawings; one holds them by the hand or hangs them on the wall as pictures.38

In 1917, art critic Nicolaus Lützhøft (1864–1928) wrote about Skovgaard’s decorative works with great enthusiasm:

Some of his [Skovgaard’s] most peculiar abilities appear in their loveliest form here; the enchanting lightness of touch, the confidence and power, the effortless beauty put forward in these purely decorative works imbue them with great artistic merit. Posterity will recognise the freshness and emotion in these ‘extra-curricular works’ when many of the works to which Skovgaard himself devoted more careful and greater work have faded beyond recall. His time was not a propitious one for the appreciation of applied arts.39

An accomplished embroiderer, Skovgaard’s wife, Georgia Schouw (1828–1868), translated his drawings into e.g. the seat and back of the so-called Madonna chair that was designed by M.G. Bindesbøll (1800–1856) and named after Raphael’s picture of the Sistine Madonna, a copy of which hung in the room in which the chair would be placed. Skovgaard and his wife also decorated the wooden frame underneath the seat with leaves and vines, whereas the seat was adorned by a stylised pattern. The back featured a hydrangea branch with a bird in the centre.

Staffage or individuals

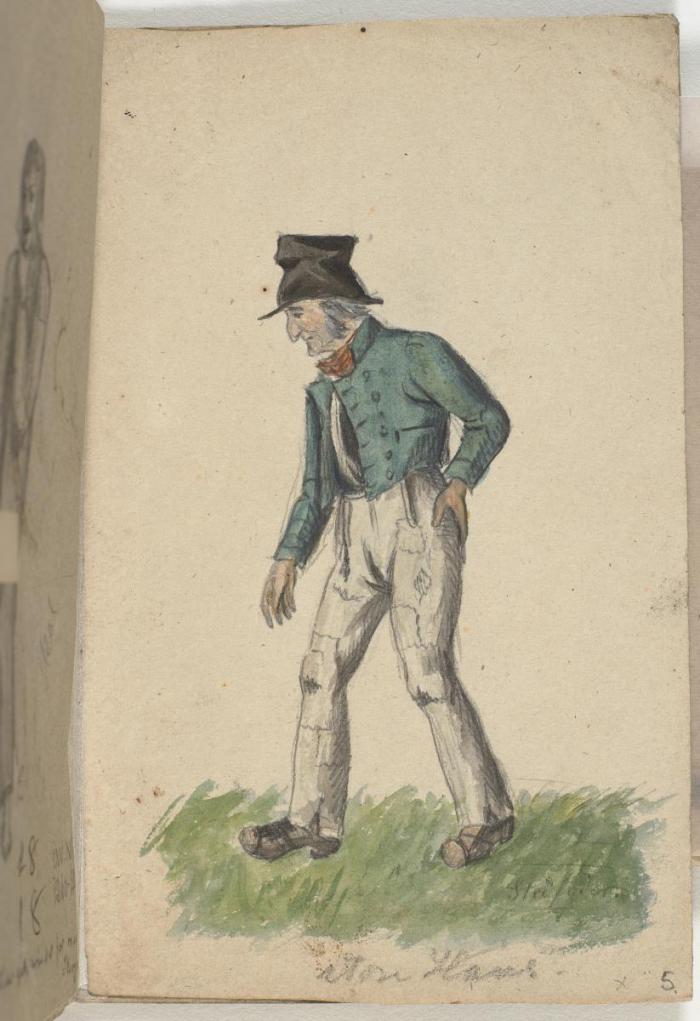

All this notwithstanding, nature was not the thing that first caught Skovgaard’s eye as a child: people did. His precocious mastery of the art of capturing the distinctive features of individual characters is apparent from his sketchbook known as ‘Tegnebog for P.C. Skovgaard, Wiebye d. 6te. Februar 1828’ [figs. 17 and 18]. Here we meet one of the eccentrics of Vejby, known as ‘Store Hans’ (Big Hans or Big John),40 a man wearing a pair of much-mended trousers, a short jacket and a top hat. Another character known as ‘Snoge Lars’ (Adder Lars/Lawrence) wore a brightly coloured coat, carried a bundle on his back and a cane in either hand. The garish pattern of the jacket is almost harlequin-like, made up of ‘all patches’, as Skovgaard noted at the bottom of the paper.

Skovgaard also depicted people later in life. As we have seen, several of these figures were used in his large paintings. Others remained committed to paper only, such as his drawings from a visit to Læsø in 1848. Before setting out from Copenhagen, Skovgaard had received letters from a friend of his, Frederik Christian Krebs (1814-1841), describing the scenes and motifs that would await him upon arriving on the island. Krebs quite naturally pointed out the coastlines, the moors, the fields and the dunes, but also the distinctive houses thatched in seaweed as well as the island’s mills. He also called particular attention to the peasants in their traditional dress, writing that ‘their costume is highly original, too, even though I do not think it would have looked like that in very many places in Denmark. It is highly unusual and painterly, if not beautiful in the conventional sense of the term’.41

Skovgaard was fascinated by the women’s traditional costume, which consisted of a black skirt and waistcoat and a large white scarf around the head and neck to protect against wind and water. He depicted how these women wore a waistcoat on top of a white blouse, its silver buttons represented as small, round white circles on the paper. He did the drawing in pencil, pen and black ink and added colour with watercolours, thereby imbuing the overall impression of the costume with depth and detail [fig. 19].

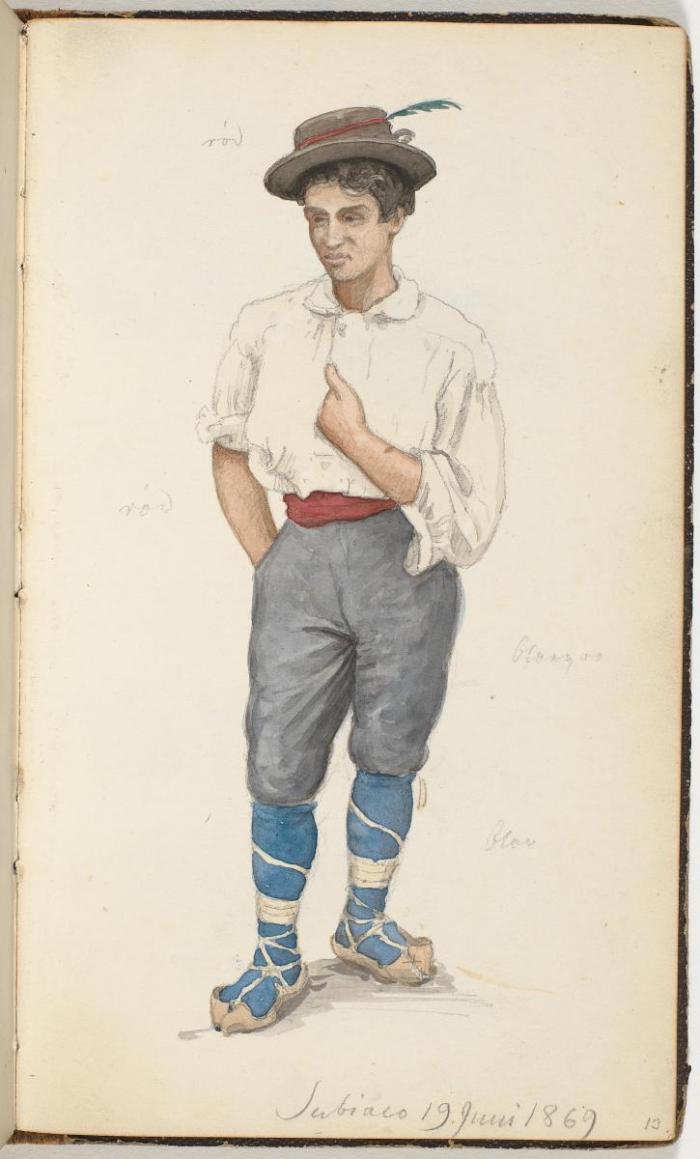

During his first trip to Italy in 1869, Skovgaard did a corresponding series of images of local peasants. As was the case in his depiction of the Læsø girl, he paid particular attention to the traditional costume of the local populace, which in the case of the men consisted of laced-up shoes, baggy grey trousers, a white shirt and a hat with a feather in it. [fig. 20]

Several renditions of the local women show their dresses loosely sketched, while their heads and hands have been embellished in watercolours. The women carry baskets: some of them balance their loads on their heads. Given that we know of no other depictions of the people that Skovgaard drew on Læsø and in Italy, we have no way of ascertaining whether these portrayals are good likenesses, but his treatment of the costumes clearly demonstrates Skovgaard’s interest in their particular design and colour.

There is a striking similarity between Skovgaard’s depictions of rural peasantry and the people portrayed by the Danish Golden Age artist Martinus Rørbye (1803–1848) on his travels in Jutland. Preceding Skovgaard by one generation, Rørbye was able to depict people with such a convincing wealth of detail that posterity has used his drawings as reliable sources of information on the original cut, colours and designs of the various forms of dress seen in his images.42

Rørbye approached his subject matter with an ethnographic eye at a time when ethnography had not yet become a separate scientific field of study – a discipline based on the systematic collection of data and knowledge through long-term field work.43 The artist became an observer who recorded the human beings in front of him without judgment or evaluation. Thus, the persons in these drawings are not staffage or stock characters, but detailed individuals.

Skovgaard’s drawings did not have quite the same effect as Rørbye’s, but a similar ethnographic gaze and empathic observation is evident in the few full-length figure drawings known from Skovgaard’s hand. Compared to the figures he would place in his monumental landscapes, these drawings appear more individualised and detailed, just as his ‘proper’ portraits do.

Like most other artists he did portraits of himself, his family and friends and others who wished to be immortalised by him. The family portraits are interesting because they grant us insight into Skovgaard’s relationship with his near and dear ones, whom he depicted with care and respect throughout his life. In 1841, while still affiliated with the Danish Academy of Fine Arts, he drew a portrait of his mother, Cathrine Elisabeth Skovgaard (1795-1851) [fig. 21], using bold contours and painstakingly precise lines reminiscent of the drawing of the Head of an Apostle he did at the academy. (see fig. 3.)

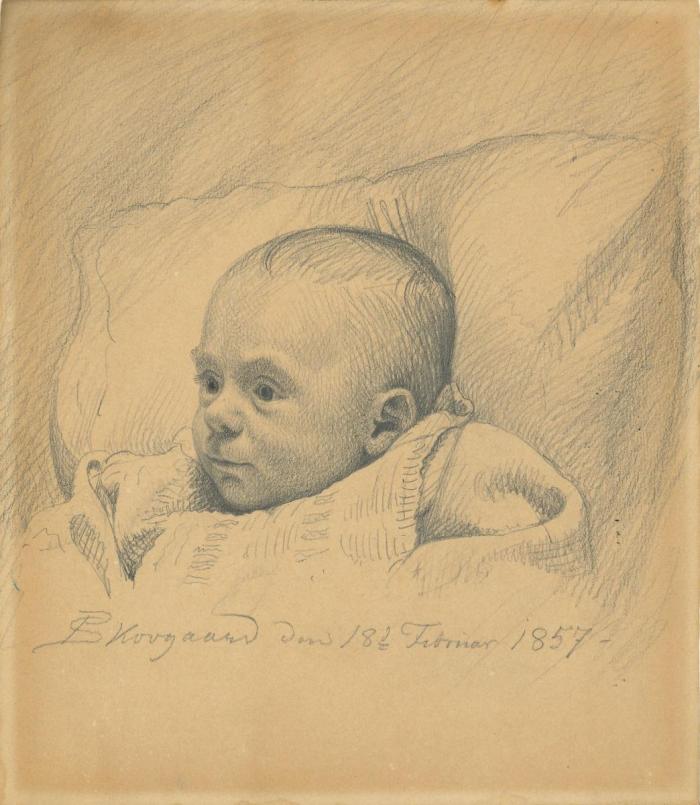

A portrait of his infant son, Joakim, done when the child was just three months old, will serve as an example of how Skovgaard sculpts the face on the paper by means of very fine lines that offer a definite contrast to the more rapidly executed hatchings in the background. [fig. 22]

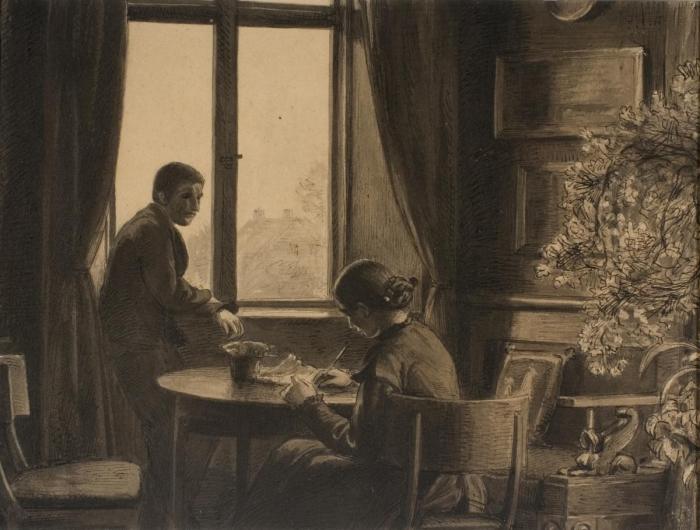

Towards the end of his own life, Skovgaard drew his other son, Niels, standing by a windowsill while a woman believed to be the family housekeeper, Miss Rønne, is engrossed in her sewing at a table. [fig. 23] The scene is infused by an intimate, private atmosphere that is further enhanced by being set in the family’s own home in Rosenvænget in the Østerbro district of Copenhagen. The drawing is done in a wash that strongly offsets the light and dark hues, making the room feel cave-like while the window is awash with bright light. It seems only natural to read the figure of Niels as a representative of youth looking towards the future through the window while the knitting figure of Miss Rønne accentuates the domestic nature of the scene. Overall, she is depicted in a manner typical of female portraits from the period.44 In portraits such as these, where the figures are not simply presented against a neutral backdrop, but in a setting with furniture and objects, those things also serve to create an impression of the sitters’ personalities and emotional lives. We are taken right into the private sphere, the setting of Skovgaard’s adult life.

An obvious course of action would be to see the differences and developments evident in the drawings as examples of how Skovgaard’s drawing skills evolved through the years, demonstrating a firmer grasp on realism and verisimilitude. However, if we include the dating of his later portraits in our considerations, they may be more usefully seen as examples of how Skovgaard used a range of different drawing techniques. The portrait of Joakim, done when Skovgaard was 40 years old (see fig. 22) is far more detailed that the one of Skovgaard’s mother, (see fig. 21), which he did at the age of 24, using broader, simpler strokes. Yet in terms of technique, the portrait of Joakim is more reminiscent of the early, aforementioned drawing of a Head of an Apostle. (see fig. 3)

This is to say that Skovgaard would alternately do drawn portraits in the academic style, as loose sketches or by means of stringent contours, using different techniques as dictated by the purpose and intended feel of the drawing. Nevertheless, all of Skovgaard’s drawings seem to share certain common traits: he has endeavoured to present his sitters with the same degree of verisimilitude that he also sought for in his depictions of landscapes and nature.

Comical drawings

The art of drawing was an indispensable tool within Skovgaard’s artistic process, constituting an important stage of the creation of his large paintings. However, some of Skovgaard’s drawings also show a side to him that is not expressed in his paintings and which also take a different tack than the other drawings presented in this article: his works on paper include overtly comical drawings too – fun, bold portraits and depictions of people. As a style, comical drawings and caricature gradually emerged in the mid-eighteenth century. In Denmark, drawings of this kind became part of the public media in weekly magazines such as Corsaren, founded in 1840. In magazines of that type, comic drawings and caricatures served as visual comments on current political and social events, and in the six years that followed its creation, Corsaren became one of the most acerbic and most talked-about champions of freedom of expression – a freedom that was being oppressed by the crown, police and judiciary. Skovgaard would often look to those strata of society for inspiration for his comic drawings, but he might also find source material in his personal experience.

As part of his academy training Skovgaard was apprenticed as a housepainter, where he supposedly met a journeyman painter so rough and uncouth that Skovgaard drew a portrait of him in the company of donkeys and pigs, adding the inscription: ‘like attracts like’.45 Much to the amusement of the other journeyman painters in the company, the drawing was presented at lunch, causing the subject of the piece to struggle fiercely to grasp the paper. Skovgaard reportedly simply said: ‘Oh, let him have it … I can draw as many as I wish’.46 The exact appearance of the drawing remains a matter of conjecture, but even so the incident testifies to how Skovgaard not only mastered the classical drawing style he had learnt at the academy, but also retained a sense of curiosity and a wish to explore different visual idioms – enough for him to dare to deviate from the norm and test his talents in various directions that were not taught at the academy.

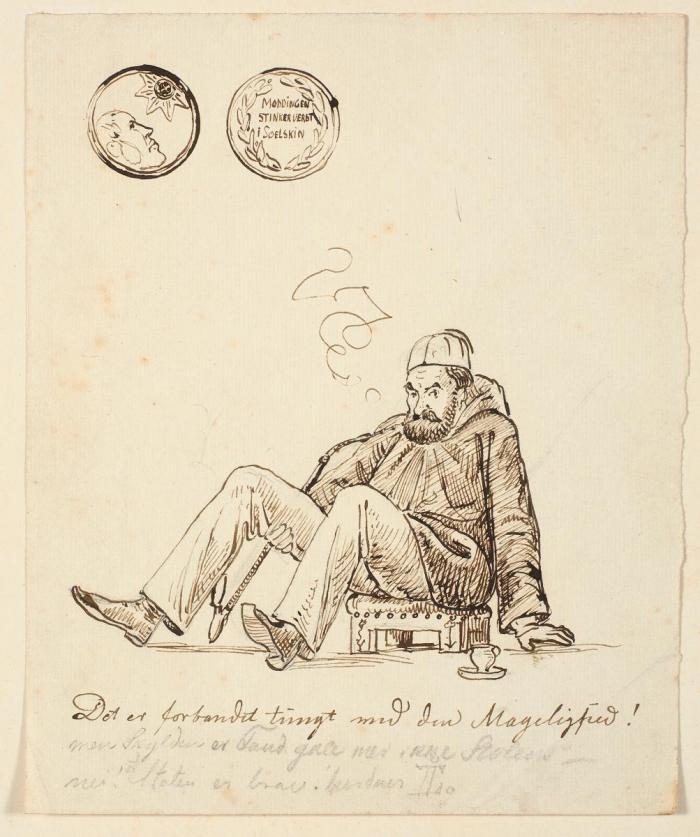

The comical drawings incorporate yet another element: inscriptions that accentuate the visual feel and content of the drawing. A portrait of Johan Thomas Lundbye seated on an oriental stool, wearing a fez and brandishing a long pipe and a cup of coffee, includes a medal bearing the legend ‘The midden stinks more in sunshine’ and a humorous inscription at the bottom: ‘All this comfort is such a hardship’. [fig. 24]

The collection at the National Gallery of Denmark is home to several drawings of king Christian VIII (1786–1848) and Frederik VII (1808–1863) that also venture into comical territory. One of the drawings shows two versions of Christian VIII, both showing him with curly hair and slanting eyes. One of the portraits depicts him with epaulettes on his shoulders. Following in the wake of two failed, childless marriages, Frederik VII leveraged the popularity he had achieved after introducing the 1849 Constitution in June that year to finally marry Louise Rasmussen (1815–1874), a fashion shopkeeper, who was made Countess Danner by royal decree. She too appears in the drawing, wearing a very large, voluminous dress with her back turned on the spectator. Frederik VII sports his distinctive moustache and full formal dress with insignia, epaulettes on his jacket and his hat held in his left hand.

Frederik VII also appears in another drawing alongside other eminent figures such as the politician and legal practitioner Orla Lehmann (1810-1870) and the influential priest, politician, poet and educator N.F.S. Grundtvig (1783–1872). Lehmann is shown in profile, his belly protruding; he holds a piece of paper in his left hand. Frederik VII also appears in profile, dressed in the same outfit as in the other drawing, his hands in his pockets. Grundtvig appears in the lower right in a half-length portrait, recognisable by his distinctive nose and pointed chin. [fig. 25] Skovgaard had close ties to the political elite and was interested in the various political and social challenges of the era, many of which centred on the abolition of absolute monarchy. Lehmann and Grundtvig were directly connected to Skovgaard: Lehmann was an influential national-liberal politician who bought several works from Skovgaard, and Grundtvig conducted the marriage ceremony for Skovgaard and Georgia and the confirmation ceremonies for both their sons.

No specific action takes place between the figures portrayed in these drawings, but a definite narrative is evident in the drawing The State Ship from 1852, where the government headed by prime minister Christian Albrecht Bluhme (1794–1866) is the butt of the joke. [fig. 26] The ship is sinking, and the politicians are forced to jettison some of their cargo. The inheritance taxes are headed for the waters, while the electoral code and the Constitution await the same fate. A member of crew throws up over the railings while Bluhme says: ‘Must the Constitution go too?’, to which the minister for culture, Carl Frederik Simony (1896–1872), replies: ‘I am afraid so’. Images such as these show us how Skovgaard was able to translate events and people into humorous pictures, demonstrating that he was much more than just a landscape painter; an insight that can only be obtained by looking towards his drawings.

Conservatively sombre or progressively far-sighted?

Skovgaard continued to draw throughout his life. He mastered a range of different drawing techniques, picking and choosing between them as required. In terms of their subject matter, the majority of his drawings are not very different from his paintings. They reaffirm what the paintings show us: Skovgaard had a keen eye for depicting nature and landscapes, right from sweeping views down to the tiniest details. His drawings merit attention for several reasons. Firstly, because they were an important tool for Skovgaard in his working process. Secondly, because his drawings include imagery that never progressed from paper to canvas in his art. Incorporating facets of Skovgaard’s activities as a draughtsman enables us to expand the narrative about his artistic endeavours as more than ‘just’ a landscape painter.

Examining the importance of drawings within Skovgaard’s overall career also gives us the opportunity to compare him up against the classic myth of the artist. His abilities and interests manifested at an early age, enabling him to work his way up from being a poor peasant lad to become a national treasure. The drawings also demonstrate how the medium allowed him greater freedom to challenge himself and push back the boundaries of his usual range of motifs. For example, we see landscapes depicted from unusual angles – through a churchyard [fig. 27] or a view from a window where the roof of an outbuilding cuts into the picture plane while a column in the centre of the picture marks out a frame through which we take in the view. These drawings feature experimental angles and points of view that challenge the dominant visual conventions which usually served as the basis of his painted landscapes. ▢

Translation by René Lauritsen

The top image is a detail of P.C. Skovgaard: Forest road. Iselingen, 1855, The Royal Collection of Graphic Art, The National Gallery of Denmark. See fig. 10