Summary

The painting of Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows entered the Royal Danish Kunstkammer before 1690. However, until a few years ago, the painting has lived an unnoticed existence in storage. In this article, the painting is subject to art historical scrutiny for the first time. Through a stylistic analysis, the author argues for an attribution to the Spanish painter Eugenio Cajés (1574-1634). Furthermore, she places the painting within the artist’s oeuvre and discusses the painting’s original context and special iconography.

Articles

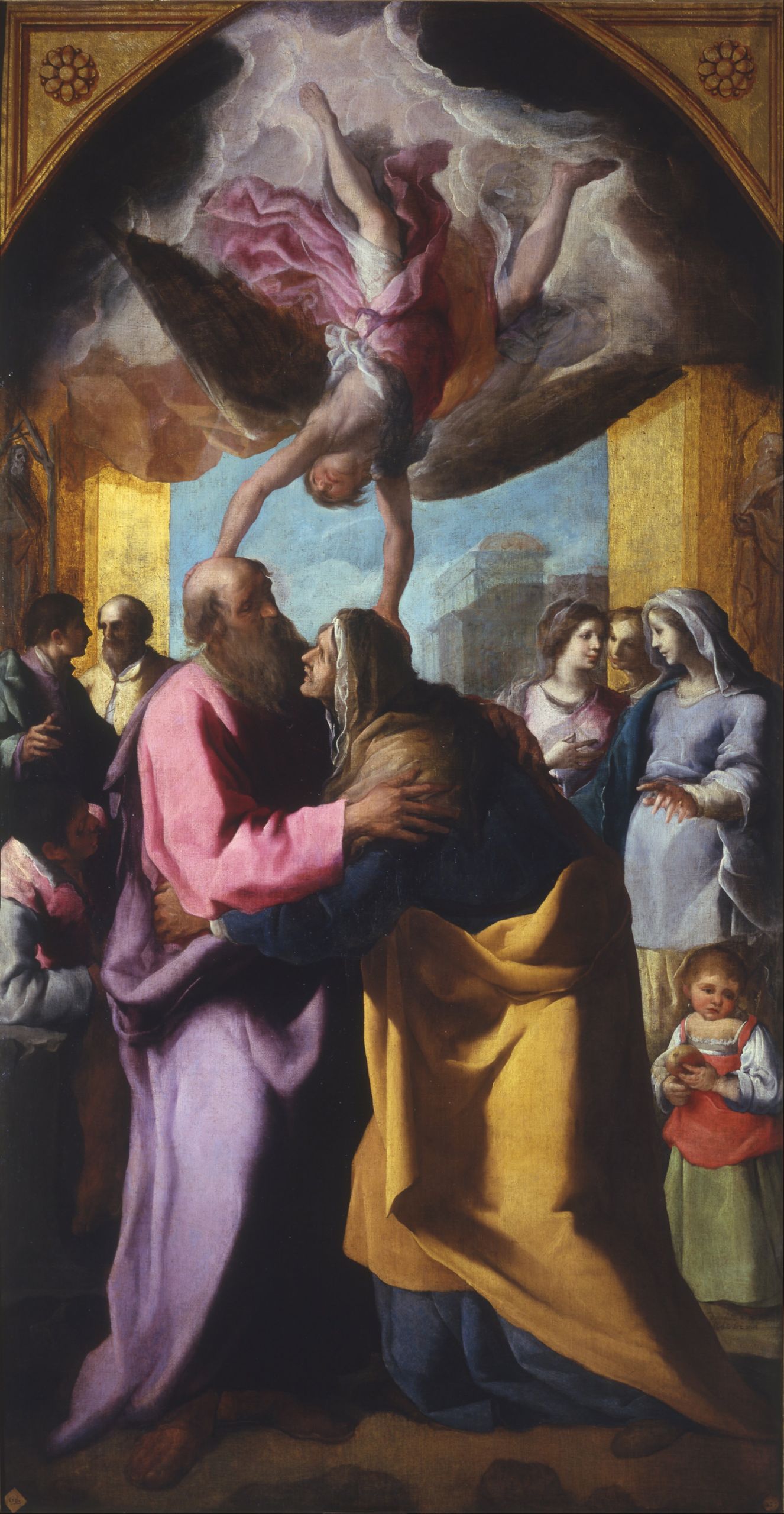

In 1690 a painting was registered in the Danish king’s Kunstkammer as: ‘A painting about St: Sebastian done by Gvido Rheno’; and again in 1737: ‘St. Sebastian Slain by Arrows, done Life-Sized by Lang Franco’ [fig.1].1 This is to say that right from a very early stage, the painting has been attributed to two different Italian painters, Guido Reni (1575–1642) and Giovanni Lanfranco (1582–1647). When the Royal Kunstkammer was closed and its collections reassigned around 1824, the painting was moved to the new picture gallery at the then royal castle, Christiansborg Castle. Later, in connection with the adoption of the Danish constitution in 1849, the royal collection became the property of the Danish nation (1849). Thus, the Statens Museum for Kunst (hereinafter SMK) was given the task of managing the royal collection of paintings. The painting of Saint Sebastian was put into storage, then placed on a long loan at Kronborg Castle and later at the central administration offices before it was once again stored away. This is to say that it has not been accessible to the general public at SMK for hundreds of years.

I became aware of the painting in connection with an audit of the museum’s stores. It had no decorative frame and was mounted on its original stretcher. Perhaps the lack of framing is the reason why the painting had never been envisioned as part of any previous hangs. Nor did its condition permit any form of public display. The painting was, without the slightest exaggeration, in a terrible state. Still, it caught my eye because its great artistic quality was obvious. It soon became clear that something had to be done.

As part of the restoration of the Saint Sebastian, a new decorative frame in a historical style that suits the painting’s subject and southern European origins was made, but this was not all; the work was also subjected to a range of technical laboratory studies, including studies of its ground (the layer applied to the support, in this case a canvas, before the actual painting in oils begins). It turned out that the ground used was similar to the one known from Madrid’s art scene in the seventeenth century.2

As a result, the working hypothesis is that the painting was not created in Italy, but in Spain, in Madrid. The article thus argues that the painting should be attributed to the Spanish-Italian painter Eugenio Cajés (1574–1634), who worked in Madrid throughout his career. On a visit to Madrid, I had the opportunity to study several signed paintings by Cajés, and in Copenhagen I was subsequently able to conduct a comparative stylistic analysis of the Saint Sebastian painting and Eugenio Cajés’s signed and dated painting The Fall of the Rebel Angels. The style analysis indicate that the painting was indeed done by Cajés.

The purpose of this article is to argue for the new attribution through a critical analysis of the painting’s style followed by a discussion of how the new work is placed within Cajés’s art. Theories on the original function and provenance of the painting are also put forward. The article further aims to generate greater awareness of the artist (who is relatively unknown in a Danish context) while addressing the Saint Sebastian motif, its literary source and Cajés’s very personal reinterpretation of the well-known saint iconography.3

What the archives tell us

Eugenio Cajés was born in Madrid in 1575 as the eldest son in a family of eight children.4 His mother was Spanish, Casilda de la Fuente, and his father was the Italian painter Patricio Cajés, who had come to Madrid to work for the king and eventually ended up marrying and settling there. Hailing from Arezzo in Tuscany, Patricio Cajés was one of the many Italian artists whom Philip II had invited to Spain to carry out decorative commissions for the large building complex (royal palace, monastery and church) El Escorial in the mountains northwest of Madrid. In 1598, Patricio’s son Eugenio Cajés married Francisca Manzano. Francisca’s mother, widow of Juan Manzano, a carpenter, applied to the king for 100 reales to go towards the cost of the wedding. Her request was granted because she was the daughter of the monarch’s former nanny. According to Eugenio Cajés’s first biographer, Jusepe Martínez, Cajés spent ‘a long time’ studying in Rome.5 His stay there can be dated with reasonable confidence to the years just before he married Francisca in 1598. Cajés was trained in the art of painting in his father’s workshop, but he also worked as an ivory turner and fresco painter.

In 1612, Eugenio Cajés was appointed royal court painter at the court of Philip IV; a position he took over from his by-then deceased father. Receiving a fixed salary of 50,000 maravedises, with extra fees added for completed works, Cajés had to support not only his own family, but also his mother and siblings.6 The salary was modest, so these were hard times for the Cajés family, as they were for so many other artists in Madrid at the time. In 1614 and perhaps several years before, the Cajés family lived in a house in Calle del Baño (now Calle de Ventura de la Vega) [fig. 7]. That year he and his wife pledged the property as collateral, thereby guaranteeing that a large painting would be delivered to the Cathedral of Toledo as agreed in the contract.7 Cajés wrote his will at the same address on 13 December 1634, shortly before his death.

The literary source of the Saint Sebastian story

The most important literary source of the Saint Sebastian story is a Roman epic poem, a romance, from the mid-400s called Passio S. Sebastiano.8 According to this source, Sebastian was a Roman officer who, under Emperor Diocletian, was recruited to the Pretorian Guard, the emperor’s personal bodyguard, because of his faithful and loyal character. Sebastian fraternised with the city’s Christian congregation and was baptised in secret. His position enabled him to protect and help imprisoned Christians, many of whom were from Roman patrician families. Sebastian unintentionally revealed himself during the emperor’s persecution of the Christians when he spoke out in defence of his fellow believers. He was sentenced to be killed by arrows and taken to a desolate area (un campo) outside the city, where his executioners tied him naked to a pole (un palo) and carried out the sentence.9 Under cover of the night, a widowed noblewoman, baptised into Christianity, came to the site of the execution to take the body with her and arrange for a dignified Christian burial. Her name was Irene, and she was the widow of Castulo, another of the city’s Christian martyrs. Irene soon discovered that the executioners had inadvertently left Sebastian alive. Legend has it that Irene had him carried home to her palace on Palatine Hill, where his wounds healed as if by a miracle. Instead of heeding the advice of his friends, who urged him to leave the city, he sought out the emperor during a public tribute to Hercules to proclaim his Christian faith in full public view. The emperor had him taken prisoner and sentenced him to death by flogging in Rome’s hippodrome.

What we see

Saint Sebastian’s eyes are half closed, black as night. They do not see the real world, gazing instead upon an inner world, the depths of the soul. The body is luminously pale, limp and lifeless, propped up only by the thick ropes that tie it to a dead tree. The face does not register the pain from the arrows piercing the torso and legs. Blood runs down in vertical streaks. Saint Sebastian’s pain is, however, keenly felt by the two women standing at his feet. Irene and her maid cry in grief-stricken horror at the sight of what they believe to be the dead Saint Sebastian.

In the almost life-sized painting, the figure of Saint Sebastian is raised as if on a stage. To his left, Irene and her companion are looking up at him. We see only their upper bodies, for they are standing below and behind the dais on which Saint Sebastian is placed, physically occupying the same level as us when we look at the painting. To the right of Saint Sebastian, the pictorial space opens up on greater depths, showing an evening sky with clouds of grey-blue and pink. In the background is an assembly of Roman soldiers and a mother with small children around her. The youngest child, cradled in her arms, has spotted Saint Sebastian, and the mother seeks to shield it from the gruesome sight. Like Irene and her maid, the mother and child express the horror mixed with fascination which we as observers involuntarily mimic at the sight of the martyred saint.

As observers, we do not immediately notice that one of the clouds is highly peculiar. It runs in a straight line from the sky down to Saint Sebastian’s torso, touching his heart region. As if by chance, the cloud forms a handshake in the middle of its sloping course. Here the artist adds a narrative about the soul’s encounter with a divine cosmic order. The cloud becomes an image of the martyred Saint Sebastian’s near-death experience. The overall expression of his face and body brings to mind the many seventeenth-century depictions of holy men and women in a state of religious ecstasy. The half-open mouth and the black slits of the eyes testify to a body of the soul, a body that meets and merges with the divine in an experience that goes beyond the boundaries of the body (ecstasy in the true sense of the word).10

A new iconography?

The scene depicted here is not only about Saint Sebastian martyrdom, but also about the soul’s deep, poignant encounter and union with the divine.11 The limp body and flaccid face with its half-closed eyes and mouth are new elements in the iconography of Saint Sebastian. He is drooping and sagging, not quite conscious, his physical state expressive of his mental condition. This mode of representation establishes a clearer connotative link to the religious mysticism of the Baroque through the ecstatic physiognomy. Might one say that in so doing, the artist has created a new iconography?

Generally, Saint Sebastian is depicted standing or leaning up against the tree trunk, often with bright, shiny eyes turned heavenwards, which was also a widespread way of portraying someone raptly receiving a vision. The combination of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom story and an inner religious experience was thus not a new interpretation of the saint motif. Rather, the artist’s innovations may be summed up as small shifts in a familiar iconography. One of these shifts concerns how Saint Sebastian is depicted in a state poised between life and death, where the soul meets the divine, visualised here as the meeting of two clouds. Another shift has to do with the presence of the women and children in the background. Their emotional responses, veering between horror and fascination, are a result of their encounter with the martyred Saint Sebastian while at the same time mirroring the very emotions the artist wishes to evoke in the viewer as she stands before the painting.

The writing of the brush – the writing of the hand

From Jusepe Martínez’s treatise Discursos Practicables del nobilísimo arte de la Pintura (ca. 1675), one may learn more of what Cajés’s contemporaries saw as his distinctive characteristics and fortes as an artist. Martínez writes: ‘his paintings were very pleasant and of great unity [in the chiaroscuro and the treatment of light] and in the depiction of celestial light and clouds, with such fine softness [morbideza] that no one has surpassed him, neither the ancients nor the modern’.12 As we shall see, such morbideza is a particularly distinctive trait of Saint Sebastian.

Many different stylistic features contribute to making this Saint Sebastian special. The narrative style has already been touched upon. Other stylistic features include the artist´s personal ‘handwriting’, his manner of painting, such as the way in which he paints clouds, skin and the folds of cloth, as well as the manner in which the different parts are composed into a whole.

Besides the clouds, several other aspects of the artist’s perception of form attract particular attention in Saint Sebastian. One stylistic feature that especially characterises the painting is the manner in which the folds of clothes are painted, for example in Saint Sebastian’s red cloak lying on the ground. Pointed ends are pulled out in ways that make the fabric feel almost organically alive. Folds are added to folds when small, individual folds are accentuated with highlights within a larger, V-shaped fold. The artist paints draperies that settle according to their own organic, yet slightly artificial pattern; a pattern reminiscent of the whorls in the cartilage of the human ear.

The Saint Sebastian painting at SMK has elements that draw on the Mannerist tradition, such as the pastel-coloured background scene that attaches itself to the main subject as an independent narrative parenthesis, or the bright, saturated colours in the red cloak in the foreground, forming a strong contrast to Irene’s dark greenish attire. But there are also elements that point towards Cajés’s mature work around 1615–1620. I am thinking here of Saint Sebastian’s black-tinted eyes and the scenic chiaroscuro spotlight in which the naked body is awash. At the same time one finds this pervasive morbideza, infusing not only Cajés’s way of painting clouds but also other parts of the composition. Thus, it makes sense, when presenting an argument for attributing this painting to Cajés, to look at selected works that represent both his early and mature oeuvre.

The first documented and preserved paintings from Cajés’s hand are two copies after the Italian painter Correggio, commissioned by the Spanish king. On 19 August 1604, Cajés received 1500 reales from the king’s treasurer in payment for his copies of Leda and the Swan and Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle [fig. 2]. Correggio’s paintings were temporarily in Madrid at the time, being en route to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague.13 Cajés’s copy of Leda was given a place in El Alcázar, the royal palace of Madrid, where it is mentioned in an inventory from 1636.14

The earliest dated and signed work by Cajés is The Fall of the Rebel Angels [fig. 3]. It is signed and dated at the bottom right: ‘euxenius Caxesi fa. 1605’.15 It was received at the Danish king’s Kunstkammer in 1701 and appears in the Kunstkammer’s 1737 inventory, being described as: ‘A painting of the same size [approximately 1 Alen high] of Lucifer cast out from Heaven, painted by Luxenius Coxei Ao 1605’.16 Cajés took his point of departure in the Bible’s account of the rebel angels and their leader, Satan, who back in the dawn of time were part of the heavenly host. When they proved themselves enemies of God and friends of evil, a battle was fought during which the archangel Michael plunged them into Hell. During their Fall, which Cajés has depicted very vividly in the lower half of the painting, the rebel angels grew tails, claws and other traits associated with devils. Here, Cajés has used chiaroscuro to portray the horrors of the underworld with eternal flames and darkness, using a palette consisting only of reds, browns and blacks. The depiction of hell forms a stark contrast to the divine realm in the upper half of the painting, where the archangel Michael and his army of good angels appear in shimmering pastels, a trait characteristic of the strong and luminous palette of Mannerism. Typical of Cajés is also the loose, sketch-like manner of painting with clearly visible brushstrokes, most evident in the good angels and the sea of clouds. The painting is, in spite of the sketch-like qualities, executed with meticulous precision. It may have been part of an altarpiece, but the modest dimensions suggest that it was originally intended as a devotional image for a private home.

The artist’s juvenile pieces also include Joachim and Anne Meeting at the Golden Gate, which is dated to 1605 [fig. 4].17 After a long time apart, the aging parents of the Virgin Mary are reunited outside the city gates of Jerusalem, which are seen in the background. The old couple embrace in the foremost foreground of the painting, while the middle ground is peopled by an assembly. The literary sources of this subject are apocryphal writings such as the Protoevangelium of James, The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and The Golden Legend. They tell the story of Joachim and Anne, who in their old age were ostracised for being involuntarily childless. In his grief, Joachim departed to the mountains and his flock, but an angel appeared to him and bade him meet Anne at the Golden Gate, for God would grant them a very special descendant.

According to legend, Mary was miraculously conceived in the very moment the two elders embraced each other, and she would, as is well known, go on to become the mother of Christ. In a bold move, Cajés has given the mystery visual form by having an angel plunge down through rays of light in the sea of clouds to unite the two old people by laying a hand on each head. Also typical of Cajés is a striking composition of contrasting colours in the saturated hues of the foreground: pink, violet and yellow, as well as in the less saturated pastels of the middle distance: green against red and yellow against lavender. The sketch-like manner of painting is especially evident in the assembly seen in middle ground, in the sea of clouds and in the angel.

A relevant example from Cajés’s mature period would be The Virgin with Child and Angels from 1618 [fig. 5].18 The subject has no direct source in the Bible, but represents a popular type of devotional image where the protagonists are pulled into the very foreground. As in the SMK Saint Sebastian, the form and colours are less Mannerist than one sees in paintings from the first years of the seventeenth century, and more influenced by the Baroque era’s chiaroscuro. The plastic perception of form, another feature also seen in the Saint Sebastian, testifies to how Cajés worked with sculpture, too. I also find other prominent elements shared by the painting of Saint Sebastian, including Mary’s eyes, which have the same sorrowful darkness as Saint Sebastian’s, as well as a cloud that outlines the contours of something recognisable, in this case the head of an angel. In the background, both paintings include a scene that comments on the main subject: The Virgin with Child and Angels shows Joseph in his carpentry workshop while the two women in the doorway must be Mary and Elizabeth. Here, too, the background scene is painted in pastel colours which contrast up against the strong chiaroscuro of the foreground. Due to the similarities, one might reasonably suggest dating the SMK Saint Sebastian to the same period as Cajés’s The Virgin with Child and Angels, which is dated 1618.

El Museo del Prado, Madrid. Inv. No. P03120.

Museo del Prado, Madrid (currently on permanent loan at the Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes, Granada). Inv.nr. P03180

Another altarpiece painting from Cajés’s mature period is the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, dated to ca. 1615–ca. 1620 [fig. 8]. The chiaroscuro is pronounced, and the Mannerist-inspired bold juxtaposition of saturated colours is also typical of Cajés’s style of painting.19 The two-metre-tall painting The Adoration of the Magi from the Prado Museum in Madrid is neither dated nor signed, and it may have been partially delegated to workshop assistants [fig. 6]. Nevertheless, it merits attention in this context, as it shares several common features with the SMK Saint Sebastian.20 Examples includes the way in which the fabric and draperies are perceived and how the background is taken over by a scene painted in pastel colours. In the following, the stylistic similarities between the aforementioned works by Cajés and Saint Sebastian will be elaborated upon in a series of comparative photos of details.

series of comparative details

Carnation: Eugenio Cajés’s copy after Correggio’s Ganymede is painted in a gentle chiaroscuro, blurring the contours and transitions. Cajés got his keen sense of painting the body in a plastic manner with finely modulated transitions from Correggio. This is carried over to the SMK’s Saint Sebastian. However, here Cajés has utilised a harsher light, as if from a stage lamp, a chiaroscuro perhaps more reminiscent of Carravaggio than Correggio.

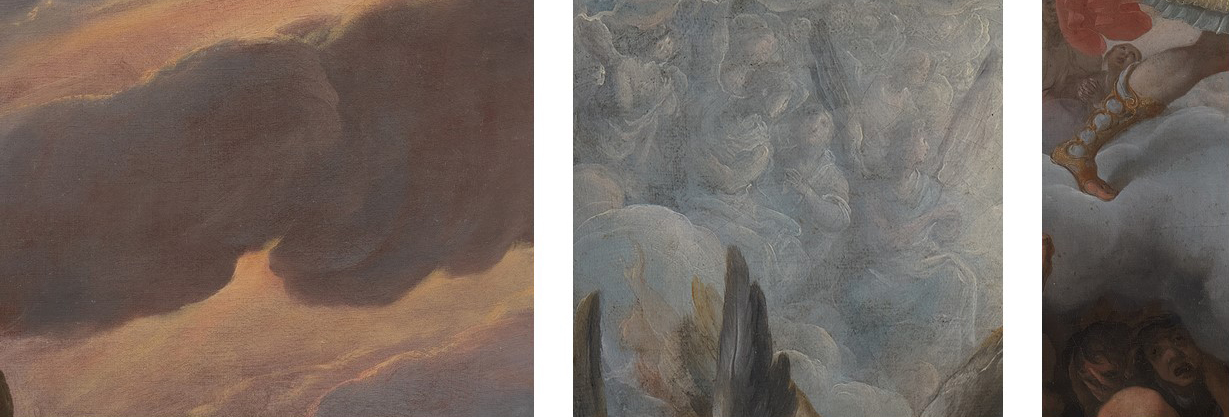

Clouds: In the Fall of the Rebel Angels, Cajés showcases his great forte: painting clouds. In his own day, Cajés became famous for his morbideza (fine, soft modulation), particularly in his cloud formations. The angelic host of the heavenly realm roam the sea of clouds as if it were a landscape of ethereal vapours, and in places the angels even blend in with the cloud formations because they are painted in the same bluish tones. The overall impression is often sketch-like because the forms are merely hinted at through a soft modulation of light and darkness, utilising occasional whitish contours done with a thin brush. In Saint Sebastian, the clouds form a handshake, very subtly hinted at by a delicate light-dark modulation of the form. The paint is thinly applied, leaving the reddish-brown ground visible in places to form the shadow. Contour lines done with a thin, ‘vibrating’ brush and a warm pink-yellow colour create the illusion of backlight at sunset, a typical example of Cajés’s sketch-like manner of painting.

Clouds: In The Virgin with Child and Angels, the angelic host of the heavenly realm occasionally merge with the cloud formations amidst the celestial glory of golden light. Restless contour fragments outline the forms in Cajés’s typical, vibrating, sketch-like brush. The same characteristic hand is seen in the heavenly region of Saint Sebastian, the place where the magical meeting between God and soul takes place. The cloud formations of both paintings are good examples of the morbideza for which Cajés was famed in his own day – an important element because divine or spiritual dimensions could be compellingly and convincingly visualised in the form of cloud formations and rompimientos (piercing the clouds with rays of celestial light).

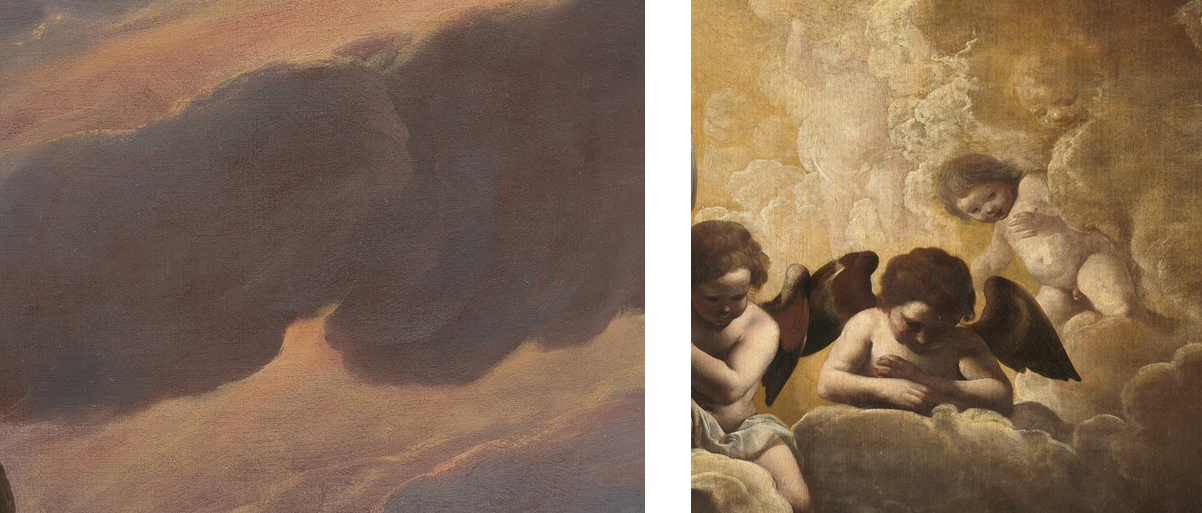

Contour: The Fall of the Rebel Angels has whitish as well as brown-black fragments of contours done with a thin ‘vibrating’ brush, creating an animated, vivid, almost sketch-like feel. Cajés has used the black-brown contour fragments in areas of shadow and whitish contour fragments where the light falls. An identical use of contours appears in Saint Sebastian, for example in the young girl’s string of pearls and in the folds of the robe. The edge of the dress is painted to form a white ‘lace’ border, an effect similar to the one seen in some of the angels’ robes in The Fall of the Rebel Angels.

Contours: Cajés’s use of light and dark interrupted contours is very clearly evident in several places in the depiction of the good angels to the left of Saint Mikael. Here they are done with the level of detail required by the smaller format. The contour fragments reinforce a clear demarcation of form in relation to its surroundings, but also serve to accentuate contrasts between light and dark. The same use of light and dark contour fragments is seen in Saint Sebastian, for example in the face and scarf of Saint Irene.

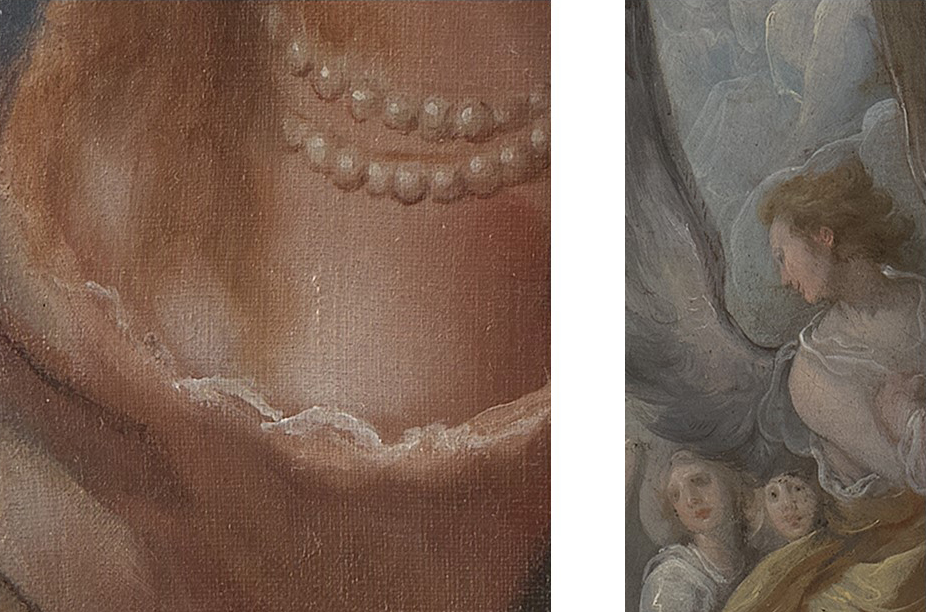

Downturned open mouth: In The Fall of the Rebel Angels, Cajés repeats a particular way of painting mouths in the terrified facial expressions worn by the rebel angels. This mouth of pain and horror can most aptly be compared to the masks of tragedy worn by ancient Greek choruses, which generally feature this distinctive, downward-turned open mouth. In Saint Sebastian, this type of mouth is most clearly found on the faces of Saint Sebastian and Saint Irene, but the basic shape is also present in in the face of Saint Irene’s young maid (this is particularly clear in X-ray images).

Draperies: The painting Joachim and Anne Meeting at the Golden Gate lets us study how Cajés’s distinctive hand reveals itself in his manner of painting draperies. Joachim’s purple cloak and Anna’s yellow ditto terminate in almost symmetrical end points, both pulled out to their respective corners in a slightly peculiar way. The folds are painted in large planes of colour, their plasticity reminiscent of sculpture. Here and there the draperies form ripples in distinctive, undulating ‘fold in fold’ sequences that can take on an almost organic feel. Cajés’s folds are reminiscent of the outlines and shapes formed by the cartilage of the human ear. In Saint Sebastian, the folds can best be studied in the red mantle lying on the ground, which features similarly pulled-out ends and the ‘fold in fold’ effect.

Draperies: The Virgin with Child and Angels offers many examples of how Cajés’s ‘hand’ reveals itself in his manner of painting folds and draperies. Often the folds form shapes somewhat reminiscent of donkey ears, such as the fold extending from the foot of the infant Christ, or the one found in the white sheet hanging from the cradle. The same donkey-ear shape is seen in Saint Sebastian in the snip to the far right.

Draperies: In The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, the white drapery (which appears to be a lining for the red cloak) shares the same perception of form and the same handling of the chiaroscuro as the white loincloth in Saint Sebastian. In the foreground of The Assumption of the Virgin Mary, the second apostle wears a dark blue cloak which meanders along the floor in the same characteristic formations seen in the red cloak of Saint Sebastian.

Eyes as black as night: In The Virgin with Child and Angels, the eyes are painted in a very distinctive way: the whites of the eye have been replaced by a blackish tint. The Virgin Mary and several of the angels have downcast eyes. Even so, one can clearly see that the iris of the eye is painted in an opaque black and the eyeball in an almost equally black colour. In Saint Sebastian, the saint is depicted with half-open eyes, hovering between life and death. The iris is painted in a monochrome black, while the eyeball (what you see from it) is painted a slightly lighter black-brown. In both paintings, Cajés has used these eyes, as black as night, to signify the looming presence of death. In the case of the Virgin Mary and the angels, the death in question is the future martyrdom of the infant Christ, while Saint Sebastian’s eyes reflect his own state, hovering on the brink of death.

Babies and pastel-coloured background scenes: In The Adoration of the Magi, Cajés has painted a background scene in the pastel colours typical of him. The scene depicts the procession of pages and camel caravans which followed the Three Wise Men. The three kings have already reached the stable, where the Virgin Mary and the Infant Christ receive them. In Saint Sebastian, Cajés has painted a background scene in pastel colours depicting a mother with a child on her lap, reminiscent in type of the Madonna from The Adoration of the Magi.

Dialogues and inspirations

Many elements in Cajés’s composition, figures and choices of colour testify to influences from other artists of his time. These may be role models whom Cajés studied on his long sojourn in Italy, or whom he met, or whose works he became acquainted with in Madrid or El Escorial. Together, these diverse influences form the conglomerate that became Cajés’s own personal style.

Cajés has adopted and incorporated inspirations from and dialogues with other artists, translating and amalgamating them to establish his own approaches and devices. The painter lets the clouds of heaven outline the meeting of two hands, thereby creating a metaphorical image of the union of Saint Sebastian with the divine. Cajés may well have found such metaphorical clouds as well as clouds that imperceptibly transform into figures in the Italian painter Correggio, who was known for his cloud formations which might occasionally take on recognisable shapes such as hands or angels. A distinctive feature that helps paint a picture of Cajés as an artist. Such interaction with Correggio’s way of painting can also be discerned in the artist’s way of painting skin and cloud formations with a gentle sfumato, where the form is modulated in imperceptible transitions with the chiaroscuro’s darkening of the local colour in the shadows.

A soul taking the form of a cloud is also found in El Greco’s vast commemorative painting El Entierro del Conde de Orgaz (The Burial of the Count of Orgaz), then as now exhibited in the Santo Tomé Church in Toledo, a city a little south of Madrid.21 Count Orgaz’s soul takes visual form as a small human being shaped out of the cloud, raised up from the earthly to the celestial sphere by an angel whose figure and luminous yellow robes bridge the two worlds. The sources regarding Cajés’s travels and movements are very sparse, but it is highly probable that Cajés saw El Greco’s masterpiece in Toledo.

The strong light falling directly onto the bare chest of Saint Sebastian, making the arrows cast long dramatic shadows that cross the vertical streaks of blood, points towards Caravaggio. The overall composition of the painting may also have been inspired by Caravaggio: as was previously discussed, Saint Sebastian is placed on a plateau, as if on a stage, while Irene and her helpmeet are at the same level as the spectator. The protagonists are pushed all the way up to the picture plane. So much so that the edge of the canvas even crops off part of the image. The scenic spotlight, the shadows and the close-up composition are all very Caravaggian features.

Where might Cajés have studied paintings by Caravaggio? In Francisco Pacheco’s treatise on the art of painting, published posthumously in 1649, one reads that several painted copies of works by Caravaggio existed in Spain. For example, Madrid was home to a painted copy after the Crucifixion of Saint Peter from Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome.22 Could Cajés have studied works by Caravaggio first-hand? The answer must necessarily remain a matter of conjecture given that nothing definite is known about his travel activities. If Cajés visited Rome around the year 1600, he may have seen the paintings that Caravaggio did for the publicly accessible churches of San Luigi dei Francesi and Santa Maria del Popolo, where Caravaggio not only contributed the scene of the crucifixion of Saint Peter, but also paintings telling the stories of Saint Matthew and Saint Paul.23 Among the nobles of Rome, it had become fashionable to establish art collections and arrange them in galleries in their Roman palaces and countryside villas. For example, Cajés may have visited the collection of paintings in the Palazzo Madama, which Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte kept open to those interested in art. Here Cajés would have been able to study paintings by Caravaggio and many other artists.24

Cajés’ Madrid

A few streets southwest of Calle del Baño, where Cajés lived, one finds Calle de Atocha, where the Church of Saint Sebastian is located [Fig. 7, nos. 1 and 2]. Given that this was Madrid’s only church dedicated to that particular saint, Cajés may have painted the scene of the figure pierced with arrows for this site. I will argue for this possibility below. Such speculation aside, it is certain that west of Calle del Baño and the Church of Saint Sebastian was the Plaza Mayor, which at the time formed the setting for everything from coronation ceremonies, theatre performances, bullfights and canonisations [Fig. 7, no. 3]. The royal family was always present as spectators, viewing the proceedings from their royal box in the grandstand at the Plaza Mayor. Madrid’s status as a capital city was ‘new’ at the time: the Habsburg king Philip II chose to reside there shortly after his accession to the throne in 1556. Under Philip II (1556–1598), Philip III (1598–1621) and Philip IV (1621–1665), no less than thirty-nine monasteries and convents and even more churches were built in the city.25 The construction of the royal palace El Real Alcázar de Madrid and the many ecclesiastical buildings gave rise to many commissions for painters and sculptors [Fig. 7, no. 4].

The Madrid art scene featured painters such as Vicente Carducho, Eugenio Cajés, followed slightly later by Francisco Collantes, José Claudio Antolinez and Diego Velázquez, as well as sculptors such as Alonso Cano and Pedro de Mena. The literary scene also flourished as never before, bringing forth writers such as Calderón de la Barca, Lópe de Vega, Tirso de Molina, Quevedo, Gongora and not least Miguel de Cervantes, who died in Madrid in 1616.

Collaboration with Vicente Carducho

The SMK’s Saint Sebastian scene may have been done for a private client as an easel painting or as part of a larger altarpiece intended for a church or monastery. I believe it is likely that Cajés was hired by Vicente Carducho to supply this painting for the altarpiece of the Church of Saint Sebastian in Madrid.

In October 1619, Vicente Carducho had taken over a major commission for an altarpiece from Antonio Lanchares, who had entered into a contract with the church on 1 June 1618.26 The altarpiece was later replaced by a new one by José de Churriguera (1665–1725).27 However, Jusepe Martínez’s Discursos Practicables del nobilísimo arte de la Pintura from 1675 provides a description of what the altarpiece looked like. Martínez describes the altarpiece at the Church of Saint Sebastian in terms that perfectly match the SMK’s Saint Sebastian: ‘the central painting is a Saint Sebastian tied to a tree, placed on high, with a mob of people at the bottom’.28 Martínez states that the painting at the top of the altarpiece was a crucified Christ, that both paintings demonstrated great knowledge of anatomy and proportions (simetria), and that the colours were very vivid.29

While Martínez’s description of the painting of the altarpiece matches the SMK Saint Sebastian well, neither the style of the figures nor the overall manner of painting fits in with the work of Vicente Carducho. Might it, then, be conceivable that Vicente Carducho brought Cajés on board as an ‘anonymous’ partner?30

Ca. 1615-1620. Oil on canvas. 228 x 116 cm. Museo Cerralbo, Madrid

We know of seventeen altarpieces, so-called ‘retablos’ consisting of several separate paintings inserted within large carved frame structures, of which Cajés is the author. In addition, we know of a large number of easel paintings.31 Cajés’s customers were mainly members of the royal household, but churches and monasteries also commissioned paintings. And Cajés collaborated with the brothers Vicente and Bartolomé Carducho on several occasions.32 Cajés’s father had already worked with the Carducho family in El Escorial on some of the major commissions associated with Philip II’s large castle complex. At the time, Cajés was just a big boy who accompanied his father on various assignments. Vicente Carducho and his brother Bartolomé Carducho also hailed from Italy, and they too had set out for Spain to work for the king at El Escorial. The next time Cajés senior and junior worked with the Carducho brothers was in 1607 on a major commission for decorative art at the royal palace El Pardo, a task that also involved other artists.33 Several collaborations followed, especially between Eugenio Cajés and Vicente Carducho, who had become a good friend.34 In 1615, the two collaborated on paintings and frescoes for the cathedral of Toledo, La Capilla del Sagrario. This was the commission which, as was mentioned above, required Cajés and his wife to pledge their property in Calle del Baño as collateral to guarantee timely delivery. The next collaboration between Cajés and Vicente Carducho was an altarpiece for the high altar in the cathedral of Guadalupe (1618),35 and the altarpiece in Algete (1619).36 Given the long history of collaborations between the two fellow painters, there would be nothing strange about Vicente Carducho engaging Cajés’s help on executing the altarpiece in Madrid’s Church of Saint Sebastian.

Never published

Despite its high artistic quality, the SMK Saint Sebastian painting has never been featured in the Statens Museum for Kunst’s printed catalogues, let alone found its way to the various hangs and shows in the exhibition rooms at Sølvgade. The first and only time the painting is described in a Danish context is in the Kunstkammer inventories from 1690 and 1737.37

This descent into oblivion may be linked to the fact that the painting had lost its ornamental frame. Perhaps this happened in the Christiansborg Palace fire in 1884, where many paintings were torn out of their frames and thrown out of the windows in the hope that this would save them from the flames. Since then, it may have been forgotten because dust and grime made it impossible to recognise its artistic qualities. Quite simply, the work became part of the large number of paintings in the SMK collection which, for various reasons, have not been assigned masterpiece status.

Concluding remarks

If the theory regarding the Saint Sebastian painting being originally intended for an altarpiece is true, this function was abolished with its incorporation in the Danish king’s collection. Apart from its purely artistic qualities, there may perhaps have been another reason why a painting depicting a suffering saint became part of the king’s collections in Lutheran Orthodox Copenhagen. In the 1689–1690 and 1737 inventories of objects in the Royal Danish Kunstkammer, the steward registered the Spanish painting as one of the objects displayed in the great chamber featuring so-called artificialia.38 Here the objects were arranged according to the materials of which they were made. Common to all the objects in the artificialia chamber was that they were admired for the great talent and technical ingenuity required to create them. The chamber was immediately preceded by the chamber of naturalia, where rare and remarkable creations of nature were exhibited side by side with the monstrous creatures that were also part of nature as created by God. Baroque audiences lavished their greatest admiration on those objects where the realms of nature and art merged. When a globe made of Florentine marble outlined the continents and oceans of the globe with its veins, this was regarded as a manifestation of nature’s rich and playful variety.39 The so-called natural curiosities in the Kunstkammer also included a polished marble slab in which the veins formed an image of Christ crucified, and small agates with veins that traced fine branches or human figures.40

Since the Renaissance, artists had incorporated natural wonders into their paintings, such as when a cloud forms recognisable figures. A seventeenth-century visit to the Kunstkammer, to say nothing of the king himself, would very quickly spot the mystical handshake in the cloud between Saint Sebastian’s chest and the sky. The cloud might be the very reason why the Spanish painter’s work had ended up in the Kunstkammer’s chamber of artificialia.

How did the two paintings, Saint Sebastian and The Fall of the Rebel Angels by Eugenio Cajés make their way to Copenhagen and enter the Kunstkammer just a few years apart? This, too, must remain a matter of conjecture. There were certainly close diplomatic relations between Copenhagen and Madrid at that time. To provide an example, one might point to Count Bernardino de Rebolledo (1597–1676), who was Spanish envoy in Copenhagen from 1648 to 1659. In addition to his work as a diplomat, Rebolledo owned a large library and dabbled in writing poems. During his eleven-year stay in Copenhagen, he wrote pieces such as ‘Selva Dánica’ (published 1655), a panegyric poem about Denmark in which he refers to Karel van Mander III as Denmark’s Apelles.41 However, there are several other possible routes by which the paintings may have arrived in Denmark. An in-depth inquiry would require an entire separate study.

The present study shows how the combination of a restoration, technical studies carried out in the conservators’ laboratory and an art-historical critical analysis of stylistic traits can provide solid arguments for a new attribution. The attribution gives rise to new considerations regarding the provenance and original function of the piece and also sheds new light on the artist’s work.

Saint Sebastian will be put on public display for the first time in connection with SMK’s major exhibition on Baroque art, scheduled to open 27 May 2023