Summary

The concept of homoerotic encoding in Western Orientalist painting has been studied almost exclusively in reference to male artists and the male gaze. Scholars have discussed female Orientalist artists such as the Polish-Danish artist Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (1819-1881) through a feminist lens, yet have largely avoided applying queer theory to her work. This paper reexamines Jerichau-Baumann’s eroticized Orientalist portraits of women with a focus on one of her most prominent models, the Egyptian-Ottoman princess Zainab Nazlı Hanım (1853-1913). Through an investigation of the queer feminine gaze as expressed in the artist’s paintings, photographs, personal letters, and written accounts, this article argues for the possibility of a less subjugating and more collaborative relationship between Western artist and non-Western model.

Articles

She was half hidden by the blue hangings garnished with costly guipure on a lovely carved ebony bed, which stood on a dais. For me she was unforgettable. In these forget-me-not coloured, aromatic surroundings Nazili lay on the soft pillow, her fragrant hair encircling her face like a halo.1

The painter Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann (Polish-Danish; 1819-1881) wrote the sensual description in the above epigraph in her travelogue Motley Images of Travel (Brogede Rejsebilleder, 1881), which offered an assortment of recollections from the artist’s travels through the Mediterranean region from 1869 to 1875. The artist was recalling a formative encounter in Constantinople in 1869 with one of her most significant models, the Egyptian-Ottoman princess Zainab Nazlı Hanım (1853-1913).2 As an established artist of European royalty and elite Danish society, Jerichau-Baumann used her social network to gain access to princess Zainab Nazlı Hanım’s royal family, where her gender enabled her to secure entry to the restricted realm of the harem. Jerichau-Baumann traveled through Turkey, Greece, and Egypt, depicting individuals across social strata in a series of “Orientalist” portraits. The terms “Orientalist” and “Orientalism” are used throughout this text to refer to the historical genre of art popularized in the 19th century which derived from the Western vision of the “Orient”— an outdated term historically used to refer to present-day Turkey, Greece, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. The objective in using the terminology here is to more precisely identify and critique the genre.3

Within this body of portraits, it is Jerichau-Baumann’s eroticized images of women that particularly demand further study, given how they subverted conventional expectations around gender, subject matter, and sexuality in the genre of Orientalist art.

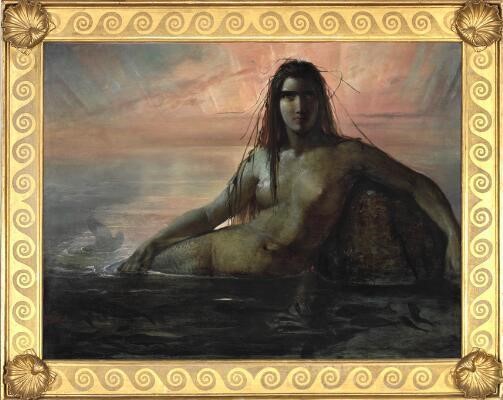

Jerichau-Baumann’s written evocation of Nazlı’s modeling session seems to directly reference the scene she painted in The Princess Nazili Hanum (1875) [fig.1], where Nazlı Hanım appears as a reclining odalisque in a harem. The artist’s textual description corresponds to several elements in the painting, including the blue hangings, the forget-me-not flowers, and the subject’s head on a pillow, encircled by her hair. The sexual overtones in Jerichau-Baumann’s written description of Nazlı Hanım as “unforgettable” as she “lay on the soft pillow” are carried over into her painting in such a way that makes it difficult to dismiss Jerichau-Baumann’s words as merely florid language emptied of erotic potential.4 Jerichau-Baumann’s inclusion of the figure of a Black woman—identified in the text as Lalla—heightens the eroticism of the scene by creating a complex triangulation between artist and models. The artist’s idealization of Nazlı Hanım as an angel with hair like a halo are contrasted with a description of Lalla, who is unfavorably compared to a watchful dog.5 This racialized dichotomy of good versus evil encapsulates the duality of desire imposed with repulsion, of association and repudiation, and the erotic tension of subordination and intimacy that permeated Orientalist art.6

Jerichau-Baumann wrote and published her self-mythologizing travelogue over a decade after the fact, and aptly refers to them as her “motley” recollections. She wrote in a style typical of Western travel literature of the time, with the aim to entertain more than to educate.7 And although Jerichau-Baumann’s descriptions of her model—one written, the other painted— can read as semi-apocryphal and hyperbolic, the fantasy stemmed from a veritable relationship between Jerichau-Baumann and Nazlı Hanım, confirmed through years of personal letters, that extended beyond the sensationalism of Orientalism. Unlike Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque (1814), with her impossible bodily proportions, Jerichau-Baumann created a portrait of a real woman, borne from an actual encounter.8

What motivated Jerichau-Baumann to produce this portrait of Nazlı Hanım, and similar works of erotic portraiture of women? Were they simply paintings that catered to male Orientalist fantasies? Or does Jerichau-Baumann’s identity as a woman require the work to be read differently? And to what extent was Nazlı Hanım a knowing or unknowing participant in the artist’s exoticizing invention?

Despite Jerichau-Baumann’s repeated exploration of the subject of hyper-sexualized women, most historians have been reluctant to give serious consideration to the possible queer associations present in her work. Beginning in the mid-2000s, art historians Mary Roberts and Julia Kuehn each examined Jerichau-Baumann’s life and work through a feminist lens and have been instrumental in bringing attention to her artistic contribution. It was not until 2016 that art historian Reina Lewis introduced the concept of the queer female gaze in associated with Jerichau-Baumann who she touched on in her text “Sapphism and the Seraglio: Reflections on the Queer Female Gaze and Orientalism.” Lewis identified the topic as a gap in the literature and has suggested a need for further exploration of this topic, from which this paper takes guidance from.9 More recently in 2021, the ARoS museum in Aarhus Denmark dedicated a comprehensive monographic exhibition. The accompanying catalogue with articles by Sine Krogh and Anna Rebecca Kledal explores her complex national identity and role as a female artist, but do not contend with her queerness.10 In addition to the catalogue article, Kledal also published the book Kunstmaleren og prinsessen. Elisabeth Jerichau Baumanns møde med prinsesse Nazili (2021), which outlines the strong socio-political undercurrents of the relationship between Baumann and Nazlı Hanım. While Kledal argues effectively for the roles both women played in the support of women’s equality and social reform, there is no consideration for the queerness embedded in their political activisms.11

Roberts has attributed Jerichau-Baumann’s sensuous treatment of her female models to the “citational nature of orientalism” and the artist’s “financial motivations,” suggesting that Jerichau-Baumann was copying her male counterparts with an eye toward the market. Roberts also asserts that the portraits of Nazlı Hanım exhibited in Europe were shown without her model’s consent, suggesting a relationship between artist and model that rested primarily on antipathy and exploitation.12 Jerichau-Baumann often did make market-driven adaptations in her work and likely pursued Orientalist themes with the goal of sales, however, it is improbable that the market alone accounts for her interest in this genre. This narrative dismisses the creative and sexual agency of both model and artist.

The paintings of Jerichau-Baumann warrant reconsideration through a queer and postcolonial theoretical framework, to challenge the prevailing assumption that Jerichau-Baumann’s sexualized portraits were mainly financially motivated imitations of the work of her male contemporaries and that Nazlı Hanım was ignorant of these works or would have disapproved of them. Evidence of the queer female gaze, expressed in Jerichau-Baumann’s paintings, travelogue, and letters points to another dimension of Orientalism, one which allows for a less subjugating and more collaborative—or in any case, a more complex—relationship between Western artist and non-Western model. The “male gaze” is a term coined in 1975 by Laura Mulvey to describe the way in which film depicts the world from the point of view of a straight man, reducing women to sexual objects, assigning them to roles that serve only to fulfill men’s desires and narratives, the “queer female gaze” by contrast casts an eroticized view while emphasizing the model’s agency.13

The intent here is not to anachronistically prove that Jerichau-Baumann or her models would have identified as a lesbian or gay individual: this is not only unverifiable but is also complicated by the lack of social acceptance around homosexuality at that time or an available language to convey same-sex desire. Furthermore, queerness is linked to, but not defined by sexual orientation, and encompasses a broad range of identities and practices that exist outside of the parameters of heteronomativity which relies on a set binary of gender roles. Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity is helpful in understanding this distinction. Butler defines gender as an artificial construct, a learned behavior dictated by society, and performed by the individual. Jerichau-Baumann’s queerness in this sense is not reliant on sexuality, but grounded in her deviation from the prescribed gender script.14 Acknowledging the potentially queer associations does not erase the inherently problematic nature of Orientalism. While remaining cognizant of these disparities, this article aims to offer a broadened understanding of Jerichau-Baumann that explores her use of the queer female gaze and connects her work to a wider lineage of queer history that is entangled in the legacy of Orientalism.15

Siren Roots

Jerichau-Baumann began her artistic training at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art (ca. 1840-1845), garnering sincere yet also pejorative praise from fellow artist Peter von Cornelius who proclaimed “she is the only real man in the Düsseldorf school.”16 She excelled in commissioned portraiture, and, with a varying degree of success, a form of patriotic romanticism. As a German-educated immigrant, Jerichau-Baumann’s work was met with divided opinions. Her style and subject matter appeared in Denmark to be decidedly German and was not received well in the wake of the First Schleswig War of 1848-1850 which spurred anti-German sentiment in Denmark.17

Some of Jerichau-Baumann’s attempts, however, appealed to her Danish audience such as an 1851 personification of Denmark, Mother Denmark, which became a famous national emblem; and her Wounded Danish Soldier, (1865) [fig.2] which was acquired by the National Gallery of Denmark the year after its creation. These idealized, narrative scenes were almost uniformly executed in an academic style with precise naturalistic detail.

For other themes that were perhaps more daring and held more personal interest, the artist’s brushwork was looser and more energetic. Exemplifying this shift in style are Jerichau-Baumann’s siren paintings. As early as the 1860s, she began depicting a series of bare-chested mermaids: mythological creatures who symbolized the lure of desire and the dangerous power of feminine seduction. She painted Mermaid (ca. 1860-1861) [fig.3] while in Rome, and commissioned the gilded marine-themed frame complete with seashells for the painting’s display at the 1861 Paris Salon.18 The siren paintings anticipate the artist’s later interest in the enticing charm of the similarly mythologized (and purportedly less civilized) sexually liberated women of the inaccessible and mysterious harem.

The theme of the mermaid was popularized in Denmark thanks to Hans Christian Andersen’s classic The Little Mermaid (1837). Andersen was a close friend to Jerichau-Baumann and later authored her biography. The painter’s mermaids appear to be an interpretation of Andersen’s fable, which caused the writer to exclaim upon seeing her canvases: “The Mermaid is absolutely spot on.”19 Andersen may have appreciated Jerichau-Baumann’s characterization of the mermaid because of how well she visually translated the Orientalist elements of The Little Mermaid. In the story, Andersen describes the sea castle in such a way that recalls Eastern architecture. The lazy disposition of the fantastical city’s inhabitants also mirrors the prejudiced Western conception of what was imagined to be the leisurely lifestyle of Eastern people. The world of the sea becomes a metaphor for the unbridgeable differences between worlds of East and West: alluring, but fundamentally different and inherently dangerous. Jerichau-Baumann manifests this idea in her mermaids by posing them as lounging odalisques set against an enchanting sky. Jerichau-Baumann would repeat this convention in her future portrayals of Eastern women.

Another layer of interest is the queer subtext embedded in Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. Andersen remained unmarried throughout his life and had apparently unrequited romantic feelings for his friend Edvard Collin (1808–1886).20 Andersen’s fairy tale has been interpreted as a veiled autobiographical account of his own doomed love for Collin who, much like Ariel’s prince, was fated to marry a princess, leaving Andersen (and his mute protagonist) to suffer in silence. Letters declaring Andersen’s feelings for Collin, and the fact that the story was published only one year after Collin’s wedding, all lend credence to this analysis.21 As a friend of the writer, Jerichau-Baumann may have been more sensitive to Andersen’s queer coding of The Little Mermaid and was able to visually reinterpret the intention in her own work by applying a queer female gaze when she traveled outside of Europe.

Lalla and Princess Nazlı Hanım

In 1869-1870, and again in 1874-1875, Jerichau-Baumann, accompanied by one of her sons, traveled to Turkey, Greece, and Egypt with the purpose of seeking out Orientalist themes to inspire her work. In describing her first meeting with Nazlı Hanım, Jerichau-Baumann wrote to her husband “Yesterday I fell in love with a beautiful Turkish princess,” and called her “the star of my Oriental dreams.”22 From these experiences emerged Jerichau-Baumann’s embellished travelogue and Orientalist paintings, which provide written and visual evidence to confirm the artist’s independent amorous sensitivity to her model. Nazlı Hanım was also immediately drawn to Jerichau-Baumann, and returned her affections in letters beginning from the time they met in 1869. In November of that year Nazlı Hanım responded to her “As I know your time is very precious since you must have so much to see and do in Constantinople, and that tomorrow you have some time…I write to say I should be most happy to see you and give you the note of introduction I promised to my cousins in Egypt.” She readily assisted Jerichau-Baumann in networking with her family in Egypt where she was headed next. Nazlı Hanım also eagerly offers to meet another day “if you prefer a visit all to yourself.”23 She later wrote to Jerichau-Baumann confiding her feelings on marrying Halil Şerif Pasha (commonly known as Khalil Bey; 1831 – 1879), “You speak of my marriage, I feel the warmth of all you say…but as yet only the preliminary arrangements are made, and we do not know when it will take place. You understand enough of the etiquette of Turkish life to know that I have never even seen the prince… if I do go to Egypt as his wife the first thing I shall think of is to invite you, my dearest friend and your daughter to come and stay with me.”24 Clearly, the two women established a strong bond from the beginning, one which was important enough for Nazlı Hanım to maintain, even if she were to get married.

At least three oil-on-canvas portraits of Nazlı Hanım were produced during her first visit to Constantinople in 1869-1870. One portrait was given to princess Alexandra of Wales (later Queen of the United Kingdom; 1844 –1925), whose letter of introduction made the sitting possible; the second remained with Nazlı Hanım; and the third Jerichau-Baumann kept for herself.25 It is unclear if the work Jerichau-Baumann kept, which she described as being in “true harem costume,”26 is the painting now titled The Princess Nazili Hanum, perhaps dated to 1875 after being reworked following the artist’s second visit to Egypt.27 Likely, sittings during her second visit did occur, as Nazlı Hanım wrote to confirm that she “shall be happy to give you sittings on the days you name.”28 In any case, Jerichau-Baumann exhibited the portrait she kept—under the title The Favourite of the Hareem—at New Bond Street Gallery in London in 1871. A review of the exhibition characterized the painting as a “veritable study from Oriental life” and, “the size of life.” This suggests that the thematically grand, and physically large-scale (over 1.5 meters wide) Princess Nazili Hanum and The Favourite of the Hareem could be one in the same painting.29

Jerichau-Baumann’s The Princess Nazili Hanum depicts Nazlı Hanım reclining in an immense swath of patterned textiles. Despite not being a nude, the contours of the princess’s body are well articulated under her clinging fabric. Jerichau-Baumann’s inclusion of a second woman, presumed to be Lalla, functions as a device commonly used by male Orientalists like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1905) or Édouard Debat-Ponsan (1847–1913) in their harem bathing or massage scenes: the inclusion of a woman with dark Black skin serves as a contrast to the porcelain whiteness of their mistress. As Linda Nochlin explained in her text The Imaginary Orient, there is often an implied lesbian subtext between the passive mistress and active servant, typically portrayed through racial and class differences in Orientalist art.30 In addition to the Orientalist grooming scenes, Manet’s Olympia (1863), made famous by the Paris Salon of 1865, also makes use of this trope [fig.4].31 It is possible that Jerichau-Baumann would have seen, or at least been familiar with Manet’s work prior to completing her own portrait, and been inspired to picture Lalla with a bouquet of flowers, just as Manet had done with the Black female figure in Olympia. Jerichau-Baumann, however, elevates the erotic potential of the picture by including Lalla not only to present the flowers to Nazlı Hanım, but also to actively shower her body with soft petals of forget-me-nots from overhead while Nazlı Hanım languishes below.

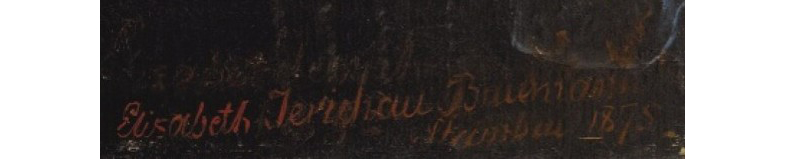

In a relaxed posture, Nazlı Hanım presents herself unabashedly in the painting, and her intent forward gaze hints at the presence of another observer in addition to Lalla: the painting’s viewer. There are several more indicators of an implied viewer’s presence just outside the frame of the canvas. Not only is the viewer met with Nazlı Hanım’s sultry gaze, but the small monkey also warily regards the intruder, much like the cat in Manet’s Olympia. Additionally, both animals have signifying potential as sexual symbols.32 The delicate gold tray in front of Nazlı Hanım holds two cups, suggesting the beverage is intended to be shared. On the lip of the tray rests a still-lit cigarette, which one can conclude the model has just set down, evidenced by the barely discernible wisps of smoke trailing from her lips, bent in an alluring smile. Many of these details have traditionally been used as artistic devices to invoke the presence of an implied male gaze. Here, however, this masculine invention is undermined and redirected through the bold, red signature, declaring in sizable letters beneath Nazlı Hanım’s feet: “Elisabeth Jerichau Baumann Stambul 1875.” The artist’s signature in this case serves as an unmistakable marker of a female gaze, thwarting any pretense of the subjecting male gaze. Interestingly, it appears that her signature was at one time erased and reapplied in her hand just below the original.33 While the explanation for this correction is difficult to ascertain, it may support the idea that Jerichau-Baumann started and signed the work in 1869-1870 while in Constantinople (known at that time as Stambul), then made revisions after she saw Nazlı Hanım during her second trip, and subsequently resigned the updated work in 1875. Nevertheless, Jerichau-Baumann’s resolution to include her name remains clear.

Despite the unmistakable eroticized nature of Jerichau-Baumann’s Orientalist paintings, scholars have been quick to rationalize them as mere imitations of works by her male contemporaries. This tendency to deny women artists sexual agency is at odds with the relative ease that scholars seem to have with associating homoeroticism with male artists. For instance, Joseph Boone’s The Homoerotics of Orientalism (2015) provides scores of homoerotic readings of Orientalist art, yet only the homoerotic practices of men in these regions are represented.34 In my view, the erasures of female sexual agency seem to stem from a social-constructed predisposition to assign heterosexuality to women.

Jerichau-Baumann’s work was clearly influenced by the hyper-sexualized Orientalist tropes of artists such as Delacroix, Ingres, and Gérôme. Undeniably the artist repeated motifs such as the reclining “odalisque” that reaffirm Western stereotypes of the harem fantasy. Yet the dynamic is complicated when the traditional eroticizing male gaze is supplanted with an equally eroticizing female gaze taken from real-life experiences. Orientalism offered Jerichau-Baumann a veil of ethnographic conventions which allowed her to navigate the otherwise immoral field of homoerotic portrayal. Her sexualized paintings of women could be simultaneously understood as catering to the expectations of a Western audience while also acting as documentary records of another culture to which she had exclusive access.

Nazlı Hanım’s Cultural Hybridity

Jerichau-Baumann’s ‘harem’ paintings have an advantage over those of her male contemporaries such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) or Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), in that her paintings own an enhanced sense of authenticity thanks to her first-hand access to women-dominated spaces and her engagement with specific models. Broadly defined, a harem is the private quarters of a household reserved for women and children, and did not resemble the Western conception of a hidden world of excess and sexual deviance. While the male-dominated genre of Orientalism tended to characterize these spaces as existing in a vacuum, unadulterated by the influences of the West, Jerichau-Baumann’s observations did not entirely discount the presence of cross-cultural exchange. In her writing, Jerichau-Baumann often laments the infiltration of Western influences on Eastern culture. And yet, ironically, she understood it was primarily this condition of cultural hybridity that granted her access to begin with.35

Jerichau-Baumann’s gender afforded her the possibility, but did not guarantee, automatic admission to the sphere of the harem. In the case with Nazlı Hanım, there was an added layer of restriction as it was an imperial harem, and Jerichau-Baumann first needed the permission of the princess’s mother. Societal portraiture common in Europe, was unusual in Turkish visual culture at this time. It clashed with the Ottoman tradition of portraiture that favored the stylized miniature technique which resisted strict mimesis. A very specific set of circumstances allowed Jerichau-Baumann the unique privilege of entering the harem and painting Nazlı Hanım in the style of Western realist portraiture.

Nazlı Hanım’s family existed within a social milieu of the Ottoman Empire that was better primed to accept Jerichau-Baumann because of their immersion in Western culture. Her father studied in France and was a strong proponent of Western-style constitutional government and political reform.36 Nazlı Hanım was educated by an English governess and was fluent in French, English, Ottoman, and Arabic. Nazlı Hanım traveled frequently and in her marriage to the notable art collector and Ottoman ambassador to France Khalil Bey, who exposed her to trends in Western art. Nazlı Hanım’s family background and her multicultural education created an environment that predisposed her, and her family, to be more inclined to push the boundaries of Ottoman social customs.

Scholars such as Roberts and Kuehn have asserted that Nazlı Hanım was unaware that Jerichau-Baumann cast her in the role of exotic seductress. Since there is no documentation that Nazlı Hanım ever saw the more sensual portraits of herself, the assumption has been that the artist intentionally hid her work from Nazlı Hanım and that had she known of their presence in exhibitions she would have felt embarrassed or betrayed.37 However, Nazlı Hanım’s own feelings about this form of exhibitionism may be more complex.

Jerichau-Baumann first met Nazlı Hanım in 1869 at her father’s seaside mansion in Istanbul, where she held domain over the entire second story which has been described as a haremlik; the private portion of upper-class Ottoman homes reserved for women. The princess, however, received both male and female guests.38 This space included a reception room, great library, and concert hall, all furnished and decorated in the current European style, complete with chandeliers and an Erhard piano that she regularly used to entertain elite guests. (Other guests had included Princess Alexandra and the French Empress Eugenie.) The imperial harem sustained the indulgent and opulent conception of how the West believed the harems operated while also disrupting other parts. The princess’s Western-style soirees represent a type of hybrid-harem that embraced both Eastern and Western societies, and in particular the art of portraiture. Nazlı Hanım gifted Jerichau-Baumann a small signed photograph (carte de visite) of herself on one of Jerichau-Baumann’s visits, most likely the second visit in 1874-1875, based on Nazlı Hanım’s mature appearance [fig.6].39 This exchange of portraits supports the idea that Nazlı Hanım was amenable to the distribution of her image overseas, and if considered to be received during the artist’s second visit, reinforces the possibility that The Princess Nazil Hanum was the same portrait exhibited in 1871 and reworked and redated in 1875 based on Jerichau-Baumann’s second visit with the princess.

Cigarettes and Women’s Liberation

During the first half of the 19th century, it was unusual for women to smoke cigarettes, especially in public. One visitor described Nazlı Hanım’s salon as being “covered with photographs of relations, friends, Sovereigns, and celebrities, of whom the Princess whilst smoking uninterruptedly cigarette after cigarette, spoke volubly, sometimes in English, sometimes in French.”40 The cigarette in the painting of Nazlı Hanım is therefore a small but significant detail relating to cross-cultural exchange. Many harem paintings include women smoking, but are almost always represented with the traditional hookah or long stem pipe. Jerichau-Baumann includes Nazlı Hanım smoking a rolled cigarette, typical of the Western practice of smoking at this time. In art and literature of the 19th century, pipes, cigars, and cigarettes often served as attributes of masculine power. Respectable women were rarely depicted smoking, and conversely, cigarettes served to indicate the moral degradation of a woman as the attribute of actresses, sex workers, and lesbians.41

In another portrait of an unknown sitter titled Odalisque (1869) [fig.7], the cigarette is again subtly inserted into the scene. Jerzy Miskowiak gives the painting the extended title “An odalisque from the harem of Mustafa Fazil Pasha in Constantinople looks at herself in a mirror,” which refers to Nazlı Hanım’s father.42 The model dons an elaborate gold and silk headdress with gold coins cascading through her hair. She is seated draped in a gold-trimmed translucent shawl, exposing her shoulders, breasts and abdomen, and she holds a mirror to her face in the style of a Renaissance Venus at her mirror.43 A single cigarette rests in a seashell ashtray next to a box of matches atop a small octagon table. This table seems to reappear in The Princess Nazil Hanum that likewise holds the recently-lit cigarette of Nazlı Hanım [fig. 8]. Both tables are the same size, and consist of an octagon top inlaid with a geometric design containing black triangles. Both models share a similar headdress with a central half-moon piece, long dark hair, strong eyebrows, and the same seductive, one-sided grin. The gold bracelet Nazlı Hanım wears in The Princess Nazlı Hanım resembles the pair (one she wears, and one is open on the table) in Odalisque, and the gauzy blue hanging with gold stars is repeated in the background of both paintings. The multiple similarities of the two works might suggest that Nazlı Hanım was the model, or inspiration, for both works.

Jerichau-Baumann’s appropriation of the male practice of smoking in paintings of her model—who unapologetically indulged in the vice (both in painting and in life) —may have been intended to subvert traditional gender roles. Odalisque has a more masculine quality in the broadness of the figure’s shoulders and chest, slightly squared jawline, and hair braided in a style common to both genders in Egypt. Jerichau-Baumann’s androgynous characterizations of her sitters was once noted by a European critic who, in reference to her depictions of Eastern women, recalled the “masculine quality of Madame Jerichau’s works.”44 By the early 20th century, tobacco companies in the United States began to market Turkish blend cigarettes, often advertising with images of Eastern women. One brand “Fatima” paired an image of a veiled woman on their packaging with the phrase “Always satisfying,” which pointedly advertised to men the product’s capacity to satisfy their needs with a clear analogy to the pleasures of smoking with the pleasures of women.45 For Jerichau-Baumann, the cigarette signified an infiltration into the privileges of men where smoking carried associations of a wider knowledge of intellectual life acquired through smoking rooms and cafes from which women had been excluded. It may be considered as a sort of precursor to the early 20th-century first-wave feminism that co-opted cigarettes as a symbol of women’s equality with men. Her use of the cigarette also seemed to indicate that women were equally as capable of indulging in such “masculine pleasures” of desire for nicotine, as well as the desire for other women.

Chaste Orientalism and The Female Artist

Although some of the Salon reviewers of 1861 were disappointed to see a depiction that went against the popular harem fantasies of male Orientalists, the overall positive response deemed the work appropriate for a woman to produce.48 One critic noted that “Only women should go to Turkey—what can a man see in this jealous country?”49 Browne set a precedent for Jerichau-Baumann that proved it was not necessary to produce such sexualized work to be appreciated as an Orientalist. The tame harem may have even been more agreeable to a Western audience when coming from a woman artist.

The success of Browne’s chaste Orientalism challenges the assumption that Jerichau-Baumann’s work was contrived entirely to cater to the marketability of the more hedonic brand of Orientalism. In reference to her Orientalist paintings, one critic seethed In reference to her paintings, one critic seethed that they were too was “saccharine” and “pathetic” which confirms that her work was not universally accepted.50 An alternative reading might posit that Jerichau-Baumann was motivated by her own interest in exploring the niches of genres that permitted her to create sensual images of women, just as her Danish nationalist genre and allegorical work were more lucrative than her enticing mermaid paintings but which she still chose to create.51

Water Carriers and Pottery Sellers

Jerichau-Baumann’s paintings of Nazlı Hanım were not an isolated case of the artist experimenting with an existing genre. Jerichau-Baumann also painted women on the lower rungs of the social hierarchy in Cairo, Bulak, Gizeh, and Memphis including several women selling or transporting vessels of water. In her travelogue Jerichau-Baumann writes expressively of her fascination with these women:

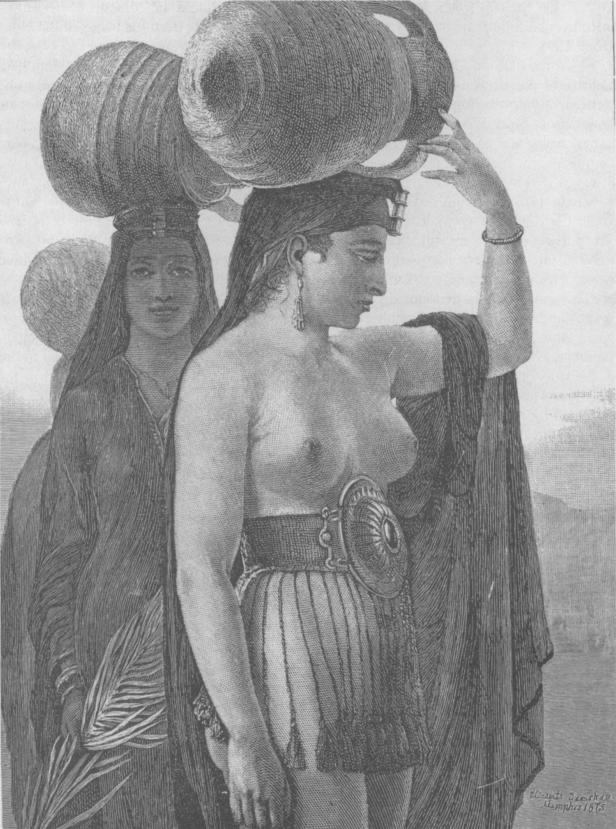

Sporadically, a single woman can be seen, walking soundlessly with her terracotta pot through the sandy fog towards the Nile. This is where I received the impression for my painting of the ‘water carrying woman by the Nile.’ One of the women let her transparent, black wrap fall for a moment, as it was very hot; she thought she would be unnoticed, and her body’s full beauty became visible to me, intensified by the rich, ornamental, Nubian bride-belt, the only jewelry the husband is obliged to give his wife when he divorces her.52

This passage is from the chapter in her travelogue entitled “Egypt 1870” and the woman Jerichau-Baumann rousingly describes is reproduced in the book in a xylograph woodblock print based on a now-lost painting [fig.10]. The reproduction is dated to 1875, but the painting was likely completed earlier, and shown at the artist’s 1871 London exhibition. Critics described her paintings as “pronouncedly ethnographical” and included “one or two female studies of Fellaheen.”53 Fellaheen is the plural term for Fellah, which refers to an agricultural laborer in the Arab World. Jerichau-Baumann’s use of these culturally specific terms was another method to add credibility to the perceived authenticity of her work.54

Two additional paintings of this genre are both similarly titled Egyptian Pottery Seller from Boulaq upon Nile (1876), and An Egyptian Pottery Seller at Gizeh (1876-78) [figs.11-12]. Both picture a sultry woman on the ground surrounded by large ceramic pottery. Both figures lean on their left arm and gaze flirtatiously out at the viewer, bearing a striking resemblance to Jerichau-Baumann’s mermaid paintings. The artist applies the same pose and confrontational gaze for the pottery seller, substituting the Egyptian landscape for the sea, golden hair ornaments for seaweed, and a clay pot for a rock.

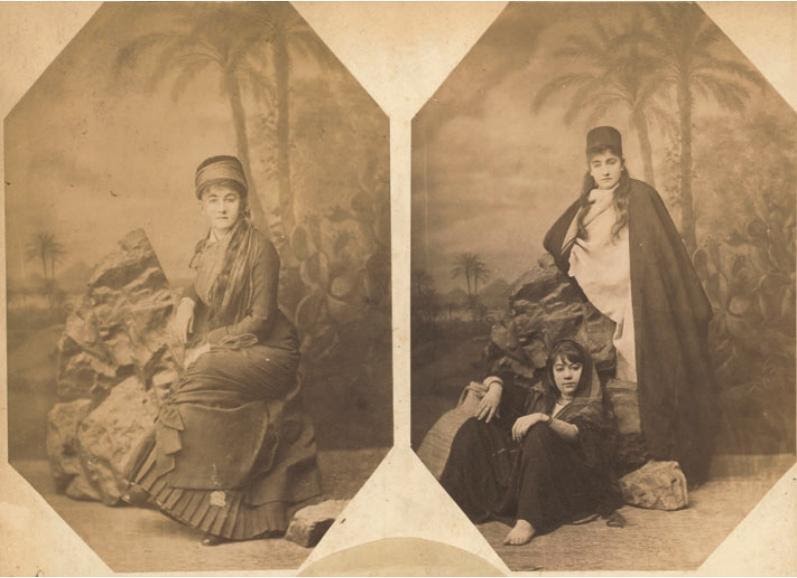

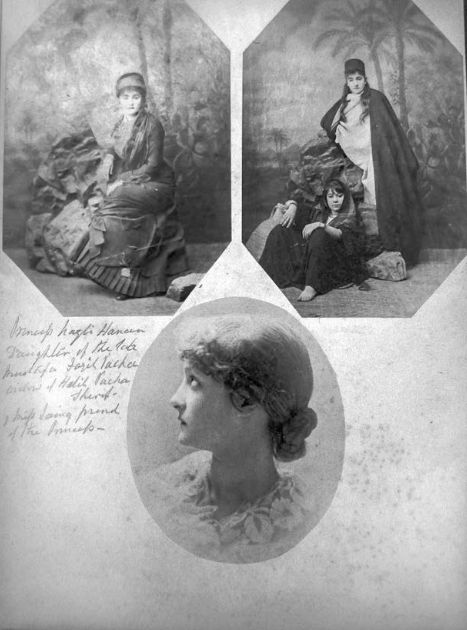

This composition would be repeated once more, although through a somewhat unexpected source. There is no documented evidence that Nazlı Hanım ever saw Jerichau-Baumann’s reclining harem portrait of her. However, there exists an intriguing photograph that suggests Nazlı Hanım was familiar with Jerichau-Baumann’s pottery seller portraits. Dated to around the 1880s, Nazlı Hanım independently choreographed a set of studio photographs [fig. 13]. In the first, Nazlı Hanım sits against a studio backdrop picturing a pyramid and palm trees, as one might see produced for tourists seeking a keepsake of their travels. She wears a contemporary Western-style dress in a dignified pose with her legs primly crossed. In the second photo, using the same backdrop, Nazlı Hanım has transformed her costume into that of a traditional Ottoman man. At her feet her female companion, dressed as a fellah, sits barefoot on the ground leaning against a large ceramic vessel, giving the identical confrontational stare as the woman Jerichau-Baumann’s pottery seller painting.55

These photographs are contained in an album that belonged to the Third Duke of Sutherland and were likely gifted to the duke by Nazlı Hanım during his visit to Cairo in 1880. Sharing the same sheet in the album is a third photograph of a young woman’s head in profile. Identified in graphite as “Miss Laing / friend of the princess” the circular photo is pasted in the album in such a way that Laing’s upturned eyes draw a direct line to Nazlı Hanım’s first honorific portrait [fig.14].56 In my interpretation, the look in Laing’s admiring stare and slightly parted lips gives the impression of sensual adoration directed towards Nazlı Hanım, who appears to be purposefully positioned on the page to infer the presence of a queer female gaze.

This connection is made especially strong when viewed alongside what today could be described as a genderqueer presentation Nazlı Hanım’s genderqueer presentation. The timing of the photograph may also be notable, likely taken the year after Nazlı Hanım’s husband died. Nazlı Hanım is labeled in graphite as “widow of Halil Pacha Sherif” (also known as Khalil Bey). According to Nazlı Hanım’s close friend Lady Layard, who met with Nazlı Hanım the week after her husband’s death in 1879, Nazlı Hanım seemed “a good deal relieved” to be free from her husband.57 The configuration of women and the triangulation of gazes seem to echo that feeling of relief and pride in finding a way to elude the male gaze.

The transgressive nature of a woman cross-dressing in the Islamic culture of the 19th-century Ottoman Empire cannot be understated, and the queer nature of challenging gender roles is unmistakable. Traditionally, women in the Ottoman Empire wore head coverings usually in the form of a veil, but as Western fashion trends took root, bonnets were also common. Educated elite Egyptian males wore a tarboosh headpiece like the one Nazlı Hanım dons, and the long white cloak with black kaftan she wears is similarly reserved for Egyptian men. Nazlı Hanım’s feminine Western dress would likely have been generally deemed appropriate, but dressing as a man would have been far more uncommon.58 It appears that rather than resisting Jerichau-Baumann’s exoticizing queer female gaze, Nazlı Hanım embraced the role, perhaps seeing a certain restorative power in the willful self-othering of her own unconventional queerness. In reclaiming these stereotypes Nazlı Hanım could engage in a visually coded language that could strike a responsive chord in a queer viewer. This photograph questions the prevailing assumption that Nazlı Hanım was an unwilling and unknowing participant in Jerichau-Baumann’s sexualized portraiture of her and offers a potentially new understanding of what may have been a more collaborative relationship.

19th-Century Art and Lesbian Iconography

Det er nyttigt at kontekstualisere relationen mellem Jerichau-Baumann og modellerne i hendes orientalistiske portrætter i forhold til It is helpful to situate the relationship between Jerichau-Baumann and her sitters for her Orientalist portraiture within the context of transnational popular imagery of lesbianism in art during the 19th century. Both Nazlı Hanım and Jerichau-Baumann were kept abreast of all the current trends in art, attending the Paris salon, and were culturally well-informed through international newspapers and magazines. Jerichau-Baumann created artwork beyond her Orientalist paintings that contained lesbian themes, such as Bathing Nymphs (n.d.) [fig.15]. Lesbian imagery was not at all new in Western art, and the motif was often found in eighteenth-century interpretations of myths like Diana and Castillo. In these mythological themes artists could playfully allude to lesbian themes with goddesses and nymphs while remaining safely within the confines of mythological story telling. By the 19th century, the theme became more widespread and was stripped of its veiled allegorical references by artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec, Manet, and Courbet, and by writers such as Maupassant, Zola, and Flaubert.59 Despite the emergence of depictions of lesbianism into popular culture, the creators and consumers of this material were generally not motivated by a desire to illustrate or understand queerness beyond its potential to titillate.

Though tumultuous, Nazlı Hanım’s seven-year marriage to Khalil Bey (from 1872 until his death in 1879), introduced Nazlı Hanım to several important artistic and cultural influences.60 Khalil Bey amassed a significant collection of paintings heavy with sexual lesbian overtones, and he commissioned Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) to paint both The Origin of the World and The Sleepers (1866) [figs. 16-17].61 The Origin of the World presents a clear depiction of a woman’s genitals. The model lies supine with her breasts partially exposed under a white dressing gown lifted to expose her abdomen, pubis and thighs. Courbet painted the woman near life-size and from a slightly elevated perspective, which provides the spatial effect of positioning the viewer between her legs, adding to the work’s naturalistic eroticism. The Sleepers similarly reflects Courbet’s Realism, with two nude women in bed in an impassioned embrace that articulates same sex desire with an undisguised clarity of image. However, the image remains rooted in the spectacle of Courbet’s radical realism.

In addition to the Courbet paintings, Khalil Bey also owned Ingres’s The Turkish Bath (Le Bain Turc) tondo (1862) depicting a swarm of lounging women bathers, ripe with lesbian implications. It is not possible to determine which paintings, if any, Nazlı Hanım had seen, as a large majority of works in Khalil Bey’s collection was sold before their marriage. However, The Sleepers was subject to a well-known scandal Nazlı Hanım might have been aware of when Khalil Bey sold the painting in 1872, the same year as their wedding. It was publicly exhibited by a dealer, which resulted in the picture being reported to the authorities.62 Understanding the possibility of lesbian sex existing, even if pandering to a heterosexual male gaze, could have impressed upon the young Nazlı Hanım that same-sex desire between women could exist, in both a general sense, and as a subject of art.

Similarly, Jerichau-Baumann may have known of Khalil Bey’s erotic art collection, but was certainly familiar with the theme of lesbianism in art, and the iconography of female sexuality. Certain elements in Courbet’s Sleepers, for example, would likely have been legible symbols for Jerichau-Baumann. The string of pearls, broken in the passions of Courbet’s lovers, alluded to the common euphemism for a pearl to represent the clitoris.63 The pearl beads visually draw the viewer’s eye to the white bedding Courbet’s dark-haired model is lifting to reveal the pink fleshy tones underneath, resembling vulva. These details reemerge in Jerichau-Baumann’s grand painting of Nazlı Hanım in which the princess wears a pearl necklace, that cascades sensuously down her chest, and the pink fleshy tones are repeated in Nazlı Hanım’s satin pants, which crease teasingly to reveal the shape between her legs. Art historian Reina Lewis has pointed out the potential eroticism of a passage in Jerichau-Baumann’s 1881 travelogue: “Oh Nazli… You budding rose surrounded by thorns you who dream about the unknown, about this world, of which you have only an inkling, you resemble a true pearl concealed between the hard tightly closed blades of the shimmering mother shell.”64 The pearl again may signify the clitoris enclosed in the “shell” of her vulva. In considering a wider network of meaning, this broader frame of reference that connects to a queer female gaze becomes more conceivable, even in the context of the flowery language often used in the 19th century that may be construed by today’s standards as erotic. Taken from this stance, homoerotic or romantic feelings could possibly have existed between Jerichau-Bauman and Nazlı Hanım.

There existed a complex double standard in which images and descriptions of female homosexuality were more accepted than male homosexuality. While lesbianism was often presented as a symptom of social decay and moral degradation common to sex work, it was not as heavily and violently policed as male homosexuality.65 This tradition of societal tolerance of lesbianism was rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of female sexuality; a tolerance rooted in invalidation. This misogynistic ignorance viewed lesbian sexual experiences to be inadequate and frustrating, and therefore unthreatening. For this reason, images of female lovers appealed to the male heterosexual viewer as fantasies free of another man.

Theatrical Sapphic Orientalism

The presence of a sexualizing female gaze on the part of Jerichau-Baumann, and the evidence of Nazlı Hanım’s irreverent genderqueer parody of Orientalist tropes invite new interrogations of a societal impulse that blindly assigns heterosexuality to all women. The queer coding embedded in 19th century Orientalism carried through to the 20th century when a language to self-identify as queer became more accessible. The overt nature of sapphic Orientalism became prevalent in theater performances, especially in France and Britain (the biggest exporters of Orientalist culture). Literary critic Emily Apter has explored this phenomenon of Western reapportion of Orientalist stereotypes in her essay “Acting Out Sapphic Orientalism,” (1994), in which she describes how the salon and stage became locations for the activism of queerness.66

Maud Allan, for instance, was a prominent queer dancer who performed as Salomé in the 1906 production of Vision of Salomé (inspired by Oscar Wilde’s eponymous play), which toured Vienna, London, and New York. Ida Rubenstein, also a famous out queer woman, played Cleopatra in the Ballet Russes’s Paris production in 1909.67 The French writer and actress Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873–1954, French) and her gender-nonconforming partner Missy (Mathilde de Morny, 1863–1944) performed together in the play Dream of Egypt [fig.18]. Missy performed as a western Egyptologist who discovers a mummy, revealed to be Collette when Missy teasingly unwraps and shares an on-stage kiss with her. The Orientalist contours of the performance and correlated lesbian overtones are transparent. The audience understood the implications clearly, which caused spectators to hurl insults such as “Down with the dykes!”68 The Orientalist tropes adopted by queer women also speak to the race and class positions that enabled Jerichau-Baumann’s work. Despite enduring harsh criticism, Ida Rubenstein, Maud Allan, Colette, and Missy were all white women of class and wealth whose position could more easily afford them the space to exercise their sexuality publicly.

Similarly, Nazlı Hanım’s position permitted her a protected space to perform her own transgressive practices of negotiating between an idealized West and an eroticized Eastern other and could freely participate in the stereotypes that were developing into methods of queer coding in which sapphic love could be employed and recognized. The harem portraiture of Jerichau-Baumann permitted both artist and model to engage the queer female gaze within the confines of existing stereotypes that allowed for a certain slippage between performing and acting out sapphic Orientalism. The campy, over-the-top nature of Jerichau-Baumann’s exaggerated displays of sexuality in her painting and writing anticipate the same theatricality of queer culture that is well-known today.

After nearly a decade since their first encounter, Nazlı Hanım wrote to Jerichau-Baumann lightly poking fun at what she perhaps viewed as Jerichau-Baumann’s naive Western brand of feminism. “Your idea that the constitution must give (at once) our women freedom much amused me; for this cannot be for long years yet to come and though there are many who think it utterly impossible, I am not one of them.” Nazlı Hanım states her lack of confidence in the swift revolution Jerichau-Baumann espoused, but firmly declares her belief in an emancipated future for women.69 Within this in-between space of apprehension and ambition grew networks of remarkable ingenuity between women navigating the social confines unique to their time and location. The overlaps and distinctions of these experiences highlight the more personal details of their lives that have until recently been shrouded in ambiguity.