Summary

This article reviews Denmark’s participation in the Venice Biennale with emphasis on the period 1940 to 1960 – from the problematic participation in the fascist ‘War Biennale’ during World War II to the post-war rebirth of the Biennale as a facet of a modernist and internationally oriented art world. The article’s focus falls on the Biennale and on Denmark’s participation as an effort to represent the current age and the radical developments seen in the exhibition format itself these years, changes which in many ways gave rise to the curated contemporary art exhibition as a focal point for the art world – including art museums. In doing so, the article also sheds light on the National Gallery of Denmark’s central role in the organisation of the exhibitions in Venice – and the challenges posed by the new focus on exhibitions for museums and other stakeholders alike.

Articles

The first Venice Biennale took place in 1895, and its long and problematic prehistory – especially its affiliation with fascist Italy before and during World War II – could have prevented it from becoming an international rallying point in post-war Western Europe. But even though the Biennale was, from 1948 onwards, ceaselessly governed by political interests – now compounded by the Cold War’s mobilisation of culture, in Italy and internationally – it became a stage for significant developments in art and how it could be exhibited. A contemporary reviewer, Gunnar Jespersen, wrote in 1960: ‘The biennial is not a reliable measure of value, but a useful barometer. It says nothing about what will remain, but much about what is current now’.1 Jespersen expresses a scepticism towards the Biennale arising out of its nature as a popular initiative aimed specifically at its own time, and this scepticism has to a certain extent affected the attention – or lack thereof – paid to the Venice Biennale’s diversity of interests and meanings in Danish art history. Studying what was presented at the Biennale reveals what was regarded as representative and significant to show in a given year, and especially what was seen to have international compatibility. Despite the ephemeral nature of the Biennale, the act of thinking in terms of exhibitions has left a lasting imprint. I contend that in the post-war years, the exhibition medium underwent an ideological development as well as process of organisational and practical professionalisation which extended not only to the Biennale, but also the art museums, which often took part in arranging the national pavilions.

One motivation for writing this article has been that Denmark’s participation in Venice – with the exception of Marianne Barbusse’s overview Danmark. Biennalen i Venedig 1895-1995 (1996) and Lars Rostrup Bøyesen’s article The Venice Biennale 1895–1968 (1968) – is strikingly under-represented in Danish art history writing. This is particularly surprising given that in recent years, the exhibition medium as such has been the subject of widespread academic interest. The study of the contemporary art exhibition has been seen as a way of reopening art history beyond retrospective canonisation, precisely because it shows the self-representation and variegated diversity of a given time. In particular, exhibition research, often operating under the designation ‘Exhibition Histories’2, has accentuated exhibitions as a driving force for international exchanges3 and as an entire artistic mode of expression in its right, one which has increasingly brought artists and exhibition venues together since the 1960s.4

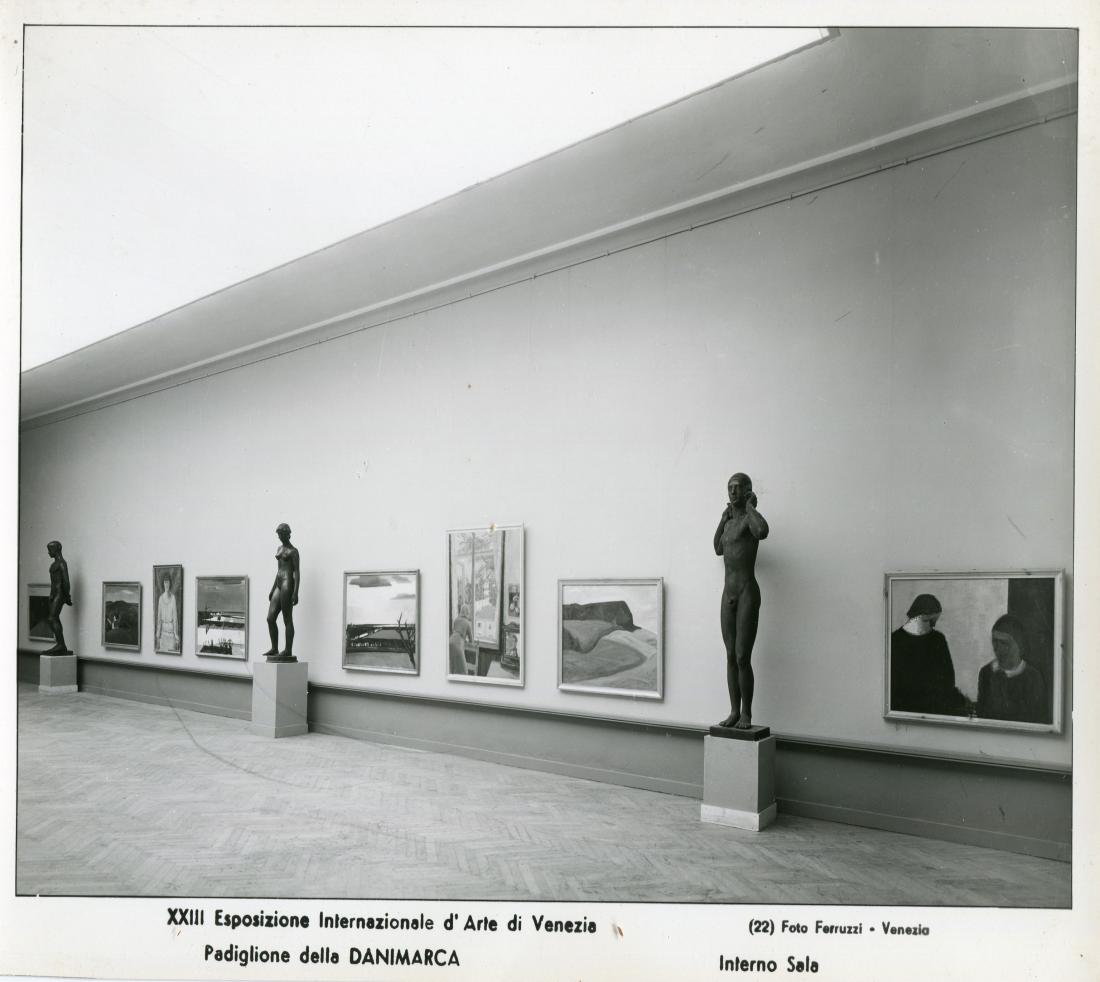

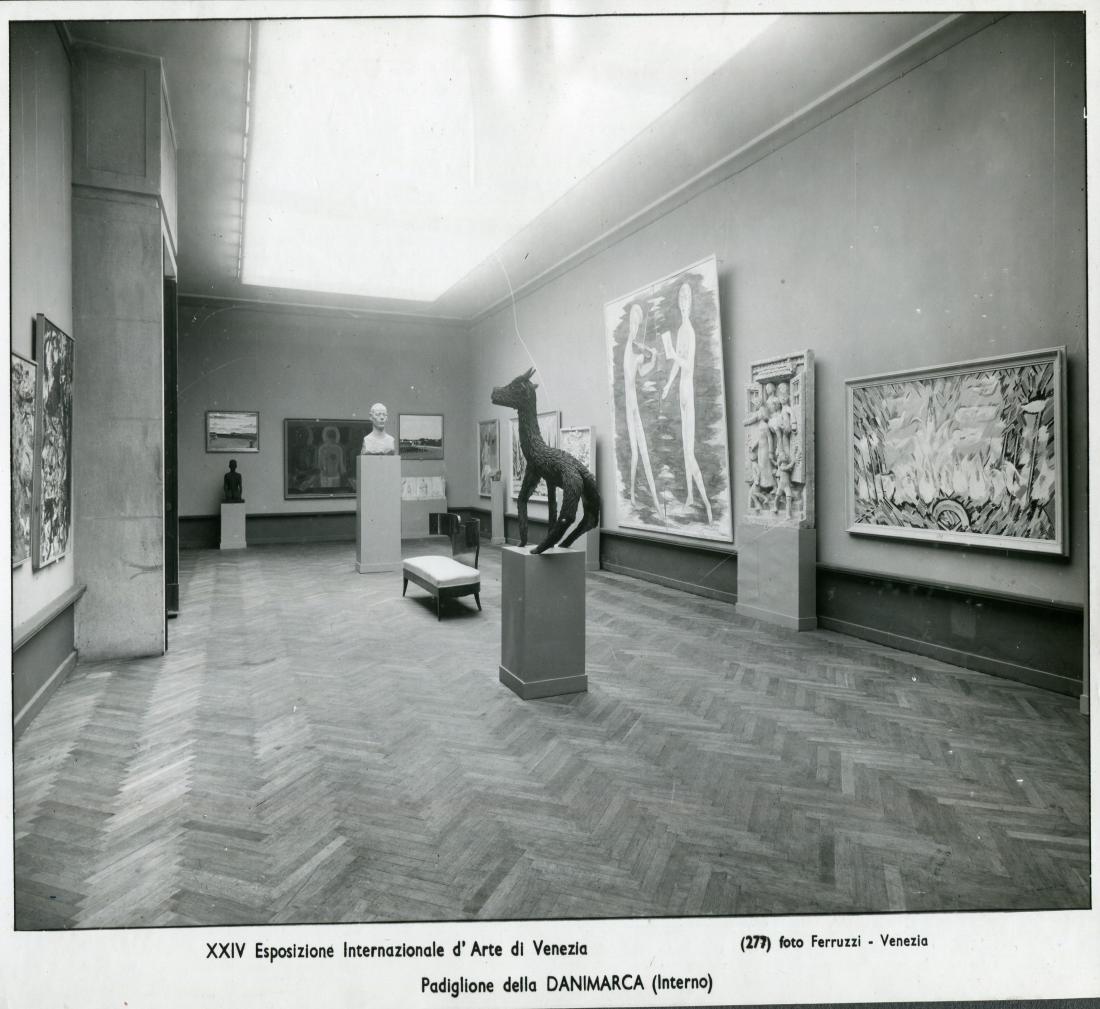

In what follows, I will analyse the exhibitions presented in the Danish pavilion at the Venice Biennale from the 1930s to the 1960s with particular emphasis on the period 1948 to 1960. The inclusion of the biennials of 1940 and 1942, held under controversial circumstances during World War II, will in itself illuminate the political conditions surrounding the exhibition and place the post-war development of the exhibition and its internationalism within a wider perspective. An oft-overlooked aspect of Denmark’s participation concerns the central role played by its national gallery, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK). The directors of the museum held a central position on the committee for the Danish pavilion and were often commissioners, i.e. responsible, for the exhibition in Venice. On several occasions, works from the national gallery’s collection were featured in the Venice exhibitions in Venice – for example, the Danish contribution to the 1942 Biennale consisted entirely in works from the museum – and the overall issue of the representation of Danish contemporary art was a pervasive theme in public discussions about the role of art and the museum’s position at the time.

An important source for my study has been the archive from the Danish Committee for the Venice Biennale, featuring correspondences, minutes of meetings and exhibition-related materials from the Danish pavilion, much of it located at SMK.5 I will also incorporate entries from the era’s art criticism and discussions concerning the Biennale; such materials help outline the central and at times controversial position of these exhibitions and of the many stakeholders involved in them.

The Biennale – poised between national promotion and international art

Art historian Caroline A. Jones has analysed the Venice Biennale as a blend of national self-promotion and an international meeting. She shows that the biennial format is an extension of the nineteenth century grandes expositions and trade fairs, with the Venice Biennale becoming devoted entirely to art. This was done in accordance with the city of Venice’s capacity and desire to make itself relevant. In Jones’s words, a double claim runs through the Biennale’s 125-year history: that ‘the (modern, Western) artist would both represent his tribe and become transcendently internationally’.6 The Biennale was to act as an incubator for the international artist through national selection, helping to slake the art world’s growing thirst for the ever-more wide-ranging, the worldwide: what was first called ‘international’ and in our own time ‘global’.7

The international aspect has manifested itself in various ways throughout the history of the Biennale. When it was first established in 1895, it was associated with the celebration of the birth of the young Italian nation, and the Venice Biennale was originally intended as a national exhibition to mark the occasion of the Italian royal couple’s silver wedding, albeit expanded with international participants to ‘shore up’ the Italian art and attract attention abroad. The exhibition, which was not officially called a biennial until 1930, was initially presented as both ‘national and international’.8

During its initial years, the Biennale was not structured around national pavilions, but took place in a central exhibition building described by the British art critic Lawrence Alloway (1926–90) as a ‘super-salon’.9

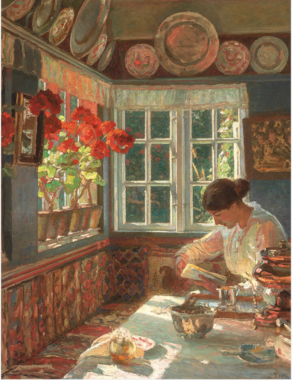

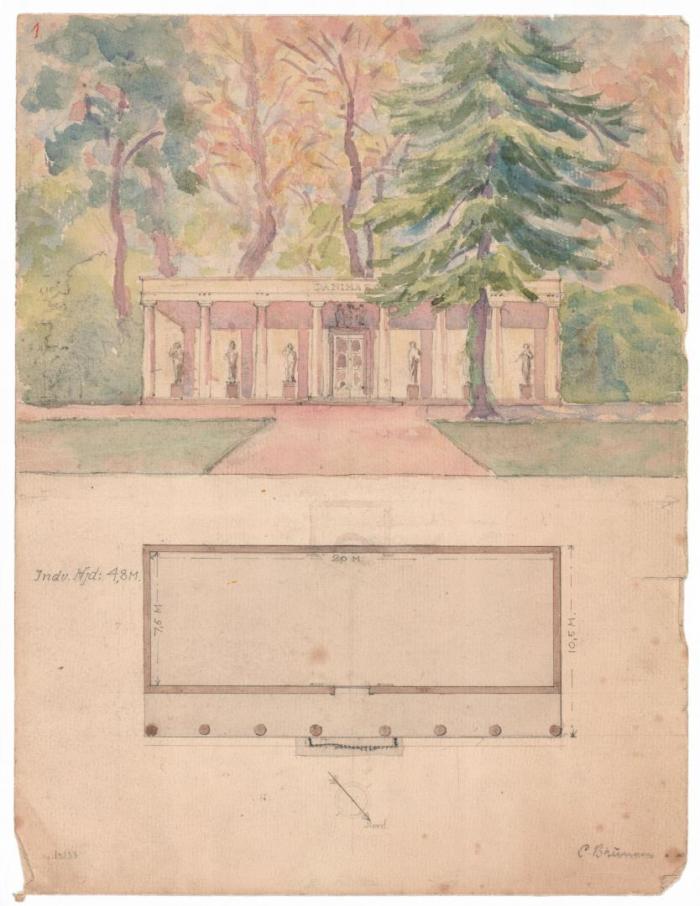

The artists were selected by an international jury which included prominent artists – such as P.S. Krøyer from Denmark (1851–1909). In 1907, Belgium was the first country to open its own pavilion, and soon other countries followed suit until the entire Biennale area in the Giardini park was almost full after just a few years. After some lobbying on the part of the well-travelled and well-connected – now virtually forgotten – portrait painter Eduard Saltoft (1883–1939), Denmark was awarded the last available space at Giardini in 1930. The plot itself was a gift from Venice to the Danish nation, and a pavilion was raised there with support from the New Carlsberg Foundation. The architect Carl Brummer (1864–1953) designed a pavilion along classicist lines, duly inaugurated for the 1932 Biennale [fig. 1]. Also in 1932, a committee comprising representatives of the key institutions and organisations on the Danish art scene was set up to select the artists presented and to arrange the exhibitions. The members were: for the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), the new director Leo Swane (1887-1968); for the New Carlsberg Foundation, professor Vilhelm Wanscher (1875-1961); for The Hirschsprung Collection, director Carl V. Petersen (1868-1938); for The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, professor Aksel Jørgensen (1883-1957); for Kunstnerforeningen af 18. November, artist Oscar Matthiesen (1861-1957); for the artists’ association Grønningen, artist Erik Struckmann (1875-1962); for Charlottenborg, artist Eiler Sørensen (1869-1953). The chairman was Frederik Graae from the Ministry of Education (under whose auspices art resided until the Danish Ministry of Culture was set up in 1961). Judging from the composition of the committee, the Biennale received serious, national attention and was clearly a priority for Denmark. However, as will be seen in this article, having such a large committee could at times make it difficult to arrive at a keenly honed selection of artists; many compromises had to be made, including between the museums’ focus on lasting values and the artists’ associations’ prioritisation of the present.

This is apparent right from the first exhibition in the new pavilion, which was not used to exhibit artists who representing the latest artistic modes of expressions in 1932; rather, the selection may be described as retrospective, featuring works from 1885–1925 and deceased artists such as Kristian Zahrtmann (1843–1917) and Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916). The next exhibition, in 1934, involved a minor change of course towards a more contemporary mode of expression, featuring artists who had had their breakthroughs around the First World War such as: Axel Bentzen (1893–1952), Harald Giersing (1881–1927), Oluf Høst (1884–1966), Olaf Rude (1886–1957), Sigurd Swane (1879–1973), Jens Søndergaard (1895–1957) and Ernst Zeuthen (1880–1938) – all of them, except Zeuthen, active in the 1920s dominant artists’ association Grønningen (founded1915). The fact can presumably be attributed to a stronger influence being exerted by Leo Swane (1887–1968) on the committee’s work; he had become a co-commissioner by this point, and from 1938 to 1950 he was officially the main commissioner of the exhibition. As Lars Rostrup Bøyesen (1915–66) says, ‘one would hardly be wrong in assuming that the strong man on the committee was Leo Swane’, who ‘was well known for his ability to get things his way’.10 Swane had been appointed director of SMK in 1931, where he was expected to act as a reformer based on his contacts on the Danish art scene, especially the circle around Grønningen. As director, Swane left his clear mark on the museum with an emphasis on early modernism and a certain reserve towards the more abstract art. Such sentiments are reflected in the Venice exhibitions during Swane’s era, where the Danish pavilion was closely linked to SMK. Generally speaking, there was a wish to represent Danish art and a focus on introducing audiences abroad to those artists that were regarded as prominent (by Swane, that is) and had been featured in the exhibitions in Denmark. This took precedence over promoting individual artists internationally, or indeed over working with the exhibition format in itself.

The War Biennale

While the Venice Biennale took place in an Italy under fascist rule (1922–1943), Prime Minister Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) actively used exhibition events to promote the regime’s prowess. In her study of fascist modernity, historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat has described this strategy as ‘a comprehensive politics of exhibition(ism)’.11 Mussolini saw the war as a formative and constructive experience that could unite the Italian people and act as the final push into modernity.12 Culture was important in this regard, and it was drafted into the service of the state. As part of fascism’s cultural policy, the Biennale’s administration was nationalised and expanded with the addition of an international music festival in 1930 and a film festival in 1932. The Biennale was still held during the war years of 1940 and 1942, while Europe and its art life were paralysed by war.

Italy entered the war as one of the Axis Powers on 10 June 1940, just before the opening of the Biennale, but there could be little doubt as to where the loyalty of the fascist regime lay in the years leading up to the war. Denmark had been occupied by German troops on 9 April, cancelling the nation’s participation. Responding immediately on 9 April, Swane, in his capacity as commissioner of the exhibition, recommended that Denmark’s participation should be abandoned; the official cancellation ‘in view of the situation’ was made on 17 April 1940.13 In that fateful year, the participating artists were to have been Knud Agger (1895–1973), Karl Bovin (1907–1985), Helge Jensen (1899–1986), Axel Skjelborg (1895–1970), Carl Østerbye (1901–1960), Th. Hagedorn-Olsen (1902–1996) og Niels Grønbech (1907–1991).14 All were figurative painters with a preference of muted, sober landscapes with modernist leanings, and all were artists whose works Leo Swane acquired for the SMK collection.

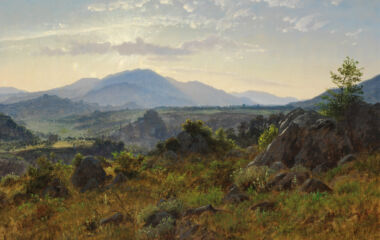

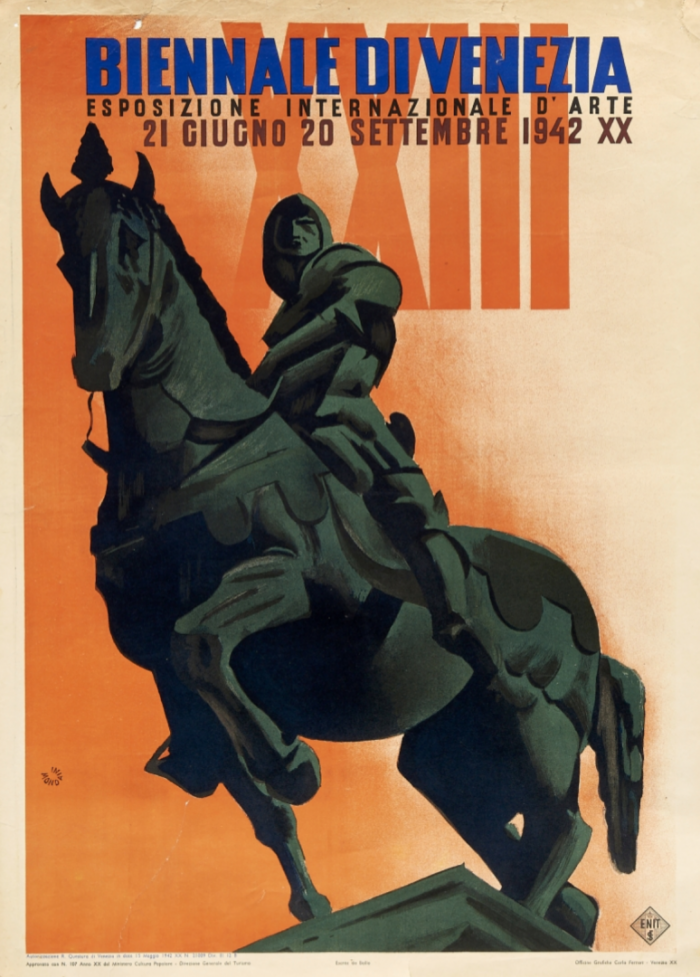

While the 1940 exhibition had been planned before Italy went to war, the 1942 Biennale was organised in wartime, as illustrated by the rather militant exhibition poster featuring the dark silhouette of Andrea del Verrocchio’s equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni (1480–88) [fig. 2]. Besides the host nation, the participating countries were those not hostile to Italy.15 Specifically, these were the Axis Powers (Italy and Germany), their allied and controlled territories (Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Hungary – and Denmark), and two neutral countries (Switzerland and Sweden). All were invited by the Italian state ‘at the request of Il Duce, who is always sensitive to the needs of the spirit’, as the catalogue said.16 At the exhibition, several of the pavilion belonging to the Allied nations had been taken over by Italian institutions and devoted to patriotic purposes. For example, the British pavilion now represented the Italian army; renamed the Royal Army Pavilion, it was decorated by a vast mural depicting St George slaying the dragon,17 while the pavilions of the USA and France had been allocated to the navy and the air force, respectively [fig. 3].

The official invitation was extended to the Danish government through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which testifies to the official status of the exhibition. However, Denmark hesitated to issue a reply, as is evident from a letter from the Secretary-General of the Biennale to Swane dated December 1941, requesting a response to the as-yet unanswered invitation.18 Swane repeatedly recommended rejecting the invitation to attend the 1942 Biennale for a number of reasons, including security, the cost of insurance and shipping in times of war, and the artists’ willingness to participate under the current conditions. He does so most notably in a statement to the ministry dated 13 February 1942, in which Swane, referring to ‘difficulties’ and ‘the completely uncertain conditions as well as for ideal reasons’ as reasons for believing that ‘all parties will be better served by abandoning participation in advance’.19 However, major interests were at stake and the question of participation could not be decided only by the art committee. After all, the invitation to Denmark had been issued to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and here, particularly on the basis of a letter from the Danish envoy in Italy, Danish participation was considered very important ‘for general reasons and for the sake of the relationship between Denmark and Italy’.20 The ministry recommended taking part with a selection of works from SMK, owned by the nation. This could be negotiated directly with director Swane without involving the Danish Biennale committee and the individual artists.21 The selection of participating countries was known to the authorities, who duly acknowledged that it was ‘not an international exhibition’. Still, they saw no other course of action than to take part on the terms stated, exhibition a selection of works from the SMK collection, chosen single-handedly by Swane.

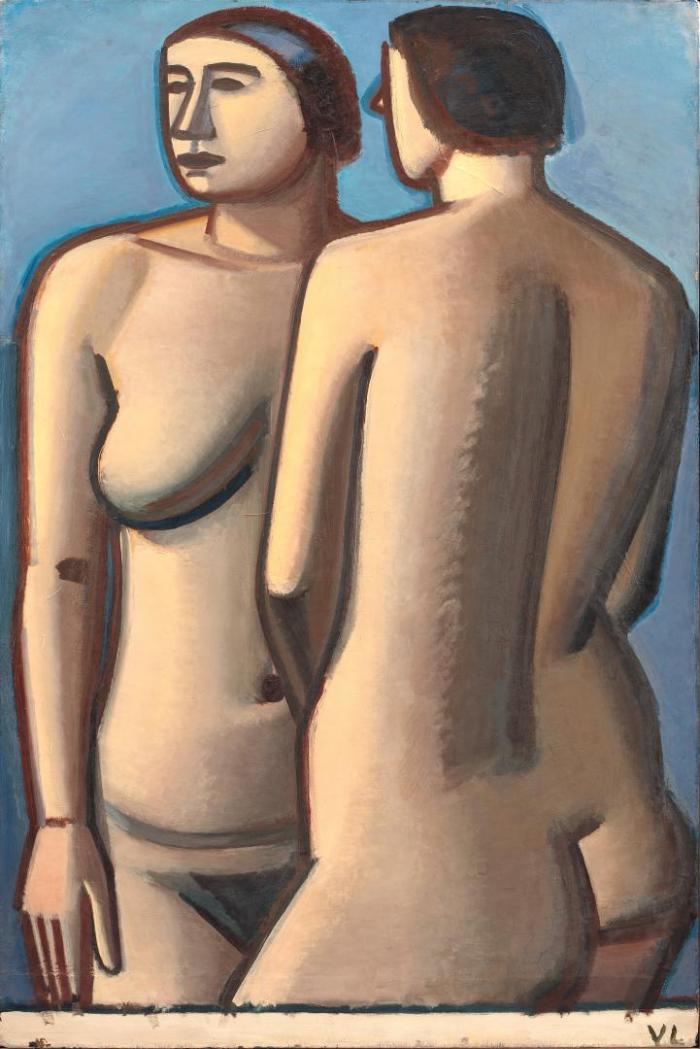

The war exhibition [fig. 4] adhered to the same approach applied in previous years, featuring the artists selected for the 1940 exhibition plus the slightly older early modernists V. Haagen-Müller (1894–1959), Axel P. Jensen (1885–1972), J.A. Jerichau (1890–1916), Niels Lergaard (1893–1982), Vilhelm Lundstrøm (1893–1950) [fig. 5] and Olaf Rude (1886–1957).

The selection of artists reflected Swane and SMK’s outlook on modern art, which was somewhat removed from pure abstraction and even further from politically charged topics and controversies. Thus, the abstract Surrealists associated with the group and magazine Linien and the younger artists of the Høstudstillingen (Autumn Exhibition) circle were absent, and none of the works presented responded directly to the dark times. While it had been customary to send Swane to Venice to set up the exhibition, this task now fell to the artist Erik Struckmann (1875–1962) who was sent to Venice to set up the exhibition. In the Danish newspaper Politiken, he would subsequently offer an enthusiastic report about an ‘unforgettable journey’ and the positive reception of the Danish artists, who were admired for their style. According to Struckmann, the Biennale was in full swing: ‘all of Italy is descending on Venice these days, where Denmark claims its place with such unforgettable poise’.22

Historian Nancy Jachec has described how, under these circumstances, the Venice Biennale was carried aloft by ‘the wrong kind of internationalism’.23 The biennial looked at its own day and age on the terms of war when, as showcased in the catalogue’s official presentation, it was dominated by scenes depicting either the war or the peaceful life under fascism. However, the Danish contribution was more subdued and withdrawn – not just from the realities of the war, but also from the fascist art ideal. Impelled by need, the official policy of co-operation had been followed in what may be the most politically controlled exhibition event in Danish history. The government’s wishes had overruled the committee’s recommendations, and SMK had to act as a buffer. The exhibition has subsequently been more or less actively written out of Danish art history and of the history of the Venice Biennale. As a result, the War Biennale of 1942 is an obvious candidate for further art historical coverage, not least in light of the fact that exhibition studies have recently included fascist exhibition culture as an aspect of modern art history.24

Under fascist leadership, the Biennale was strengthened. Paradoxically, this made its continuation after the war even more coveted: the post-war situation created a demand for new rallying points for national promotion and for a renewed interest in the international.

The Biennale relaunched, 1948–58

The response to the invitation to the first Biennale after the war, issued in 1948, demonstrates the general instability typical of the post-war period and indicates how the Biennale was associated with the fascist regime, meaning that participation was a matter which merited careful consideration. The committee discussed whether participation was safe, let alone desirable for Denmark. Swane believed that there was no longer cause for ‘ideological concerns’, but acknowledged that the ‘situation’ could change quickly.25 In 1948, the first elections in the Italian Republic were held, ushering in Democrazia Cristiana (DC) as the ruling party and cutting off the large Communist party (PCI) from influence. At the same time, tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western powers grew in scope, prompting the creation of NATO in 1949. This was the background for the Biennale’s reinvention as part of a new art world focusing on the modern and international. Nancy Jachec has analysed how the Venice Biennale was politically engaged in promoting an overall European idea with abstraction as a cultural emblem, a contrast to the realism of Communism. For the Italian governing party Democrazia Cristiana, the Biennale served a dual purpose in terms of their cultural policy: ‘anti-communism at home, Europeanism abroad’.26

The introduction in the catalogue for the 1948 Biennale spoke of art as a language that united all of mankind, reaching beyond national and ideological barriers: ‘Art invites all mankind beyond national frontiers, beyond ideological barriers, to a language that should unite it in an intense humanism and a universal family against every Babel-like division and dissonance’.27 Under the leadership of Giovanni Ponti (1896-1961) as President (1946–54) and Rodolfo Pallucchini (1908–89) as Secretary General (1948–57), the Venice Biennale was relaunched as an international exhibition with weighty presentations of European art movements ranging from Impressionism to Surrealism. This is evident, for example, from the way in which the Swedish-Finnish author and critic Göran Schildt (1917–2009) would, in his later reviews of the Biennale, speak of ‘the “big” biennials immediately after the war, when the outline of the new international art took shape’ (in 1956),28 and that the ‘the first glorious events offered unforgettable retrospective displays of Cubists, Expressionists and the other classics of modern art as an impressive backdrop to the myriad of new talents’ (in 1960).29 The second quote specifically highlights the importance of retrospective exhibitions in a reopened Europe, where museums had not yet acquired works from the latest art trends such as Cubism, Expressionism and Surrealism. The Venice Biennale became a pioneer in this field, as were the first two documenta exhibitions in 1955 and 1959, which, respectively, presented art in the twentieth century and art after 1945, particularly foregrounding the ‘world language’ of abstraction in the foreground.

In the case of the Danish pavilion, the artist Erik Thommesen (1916–2008) proposed that it ought to present an entirely abstract exhibition. The committee, which was still helmed by Swane, greeted this proposal with positive responses, but also with opposition. Typically, the debate prompted a vote on whether to favour abstract or figurative art, and the end the result was to include both.30 Hence, the final selection made was a rather more motley compromise featuring a group of thirteen artists that brought together older, figurative artists such as Olivia Holm Møller (1875–1970), William Scharff (1886–1959), Christine Swane (1876–1960) and Th. Hagedorn Olsen with ‘four abstract painters’31 Ejler Bille (1910–2004), Egill Jacobsen (1910–98), Richard Mortensen (1910–93) and Carl-Henning Pedersen (1913–2007). [fig. 6] In a subsequent evaluation report, Swane had to concede that the potentials had not been fully utilised and that the Danish show had failed to attract international attention. Interestingly, he acknowledged that the Biennale ‘has truly attained great importance as an international forum’, and, inspired by the initiatives of other countries, he recommended a tighter focus: ‘We should highlight a single, and naturally entirely contemporary artist, which in our opinion ranks among the strongest, so that perhaps only a few painters and a single sculptor exhibit’.32 In the re-invented Biennale of the post-war period, the rules of the game had changed, and each nation had to adapt to this fact. The 1948 Biennale boasted successful initiatives such as Britain’s presentation, which paired Henry Moore (1898–1986) with J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), and the gallery owner Peggy Guggenheim’s (1898–1979) collection of European avant-garde and the new American Abstract Expressionism exhibited in the Greek pavilion at the invitation of Pallucchini. This demonstration of international modernism, which involved the first-ever presentation of Jackson Pollock (1912–56) in Europe, became, like the Bienniale’s themed main exhibition, an important source of inspiration and model for the modern art museum and its structuring around American and Western European modernism.33

As a consequence of the aforementioned evaluation, the Danish contribution was pared back to just three artists 1950: Knud Nellemose (1908–97), Jens Søndergaard (1895–1957) and Edvard Weie (1879–1943). These were prominent names in a Danish context and key artists for the SMK, but hardly artists with an international contemporary profile. In 1952, with the SMK’s new director Jørn Rubow (1908–84) as commissioner, the committee went back to sending a larger group of artists: Johannes Bjerg (1886–1955), Mogens Bøggild (1901–87), Gottfred Eickhoff ( 1902–82), Adam Fischer (1888–1968), Gerhard Henning (1880–1967), Vilhelm Lundstrøm and Henrik Starcke (1899–1973) – a group of older sculptors supplemented with works from the 1930s by the painter Lundstrøm, who had very recently died. In 1954, the artists selected were Knud Agger, Arno Axelsen (1912–72), Axel Bentzen, Lauritz Hartz (1903–87) and Svend Wiig Hansen (1922–97) – after a more tightly focused selection consisting of Hartz, Asger Jorn (1914–73) and Else Alfelt (1910-1974) had been tabled. In the newspaper Politiken, the critic Walter Schwartz (1889–1958) described Denmark as occupying ‘a neatly adequate, tepid middle ground’ within the Biennale’s ‘artistic contest’34 between thirty-two nations. To Schwartz’s mind, none except for the younger Wiig Hansen had any feel for the present at all, leaving them little chance of achieving international success: ‘With older pictures by Lauritz Hartz, Knud Agger, and Axel Bentzen, we present a beautiful melody from the 1930s, very skilfully played by museum director Rubow, and pretend to be unaware that a young orchestra has long since begun playing to a different beat, one that would have resonated quite differently at a world convention’.35 A somewhat surprising critical voice appeared in the form of the former Biennale commissioner Leo Swane, who, in an essay published in Politiken on 3 November 1954, questioned the relevance of even participating in the Biennale’s ‘frenetic, vast show’ at all. According to Swane, the Biennale was a ‘mammoth market’ with no overall governing idea, far too big to properly take in, and one where the good Danish contributions would just be ‘drowned out by the hubbub’ anyway.36 However, Swane was not exactly known as a supporter of extensive exhibition initiatives, and his call to withdraw from the Biennale did not provoke much in the way of further reactions.

In the following years, the committee seems to have taken note of the criticism, leaving behind the salon format with its many artists in favour of a more tightly focused selection. In 1956, they chose to concentrate the exhibition on pairing up the painter Egill Jacobsen and the sculptor Erik Thommesen; both were abstract artists embroiled in the central currents of the time and not yet firmly established. The invitation to Jacobsen, which was sent in March just a few months before the exhibition opened, states that the selection of works must be agreed with Rubow,37 who was, then, responsible for the content of the exhibition and acted as curator. While the content was thus guided and managed in an earnest attempt at signalling contemporary flair, other aspects of the exhibition lagged rather behind. In an evaluation report penned by Lars Rostrup Bøyesen (1915–96), curator at the SMK and assistant at the exhibition in Venice, it is noted that Denmark had ‘demonstrated the poorest performance of all the nations in terms of propaganda’.38 Unlike other countries, the Danish exhibition was accompanied by no printed matter, it was poorly staffed, and it had no opening reception, which might well have attracted attention and created goodwill. The pavilion itself did not do better either, ‘with its slightly mausoleum-like temple façade and rather discreet position in a large shrubbery’.39

For the subsequent Biennale in 1958, a deliberately different mode of expression was chosen by appointing the fine-art printmakers Povl Christensen (1909–77), Palle Nielsen (1920–2000), Sigurd Vasegaard (1909–67) and the sculptor Jørgen Haugen Sørensen (1934–). Unlike the abstract artists, these figures reflected a ‘figurative, realistic’ tendency ‘characteristic of some of the young artists’, as stated in the introduction to the booklet produced to accompany this exhibition.40 This time, the title of commissioner was held by Erik Fischer (1920–2011), curator at the Royal Danish Collection of Graphic Art, and he very obviously exercised great influence on how the exhibition was compiled. The presentation of these Portrayers of Man41 stood out from the crowd at a bienniale which – taking its cues from the curatorial line adopted by the Italian main pavilion and a retrospective exhibition featuring the German artist WOLS (1913–51) – was characterised by the almost total dominance of abstract art, with the exception of the socialist realism found in the works presented by the participating communist countries. In a subsequent report, Fischer stated that the Danish presentation of print had ‘asserted itself very beautifully’ at a ‘Biennale that was 90% abstract’.42 In the same report, Rostrup Bøyesen described the exhibition’s ‘beautiful and uniform setting, which gave the hang a touch of quiet monumentality’ and that the pavilion’s interior had been painted in a muted green colour, which ‘most beautifully way made the room cohere around the exhibited works of art’, even if the pavilion was itself still ‘in need of extensive restoration’.43 Despite the challenges posed by the setting itself and the somewhat defensive strategy of employing figurative graphic artists, the efforts had, seen from the Danish side, succeeded in making the exhibitions appear more coherent.

Med tanke på, at perioden er ramme om abstraktionens helt store år i dansk kunst, både i den ekspressive og den konkrete retning, er det lidt påfaldende, at man ikke valgte at udnytte det abstrakte momentum på Biennalen. Noget tyder på, at man anså abstraktionen som for international og heller ikke ønskede at give plads til de i udlandet baserede kunstnere som Jorn og Mortensen.

Nordic collaboration – and Denmark goes solo

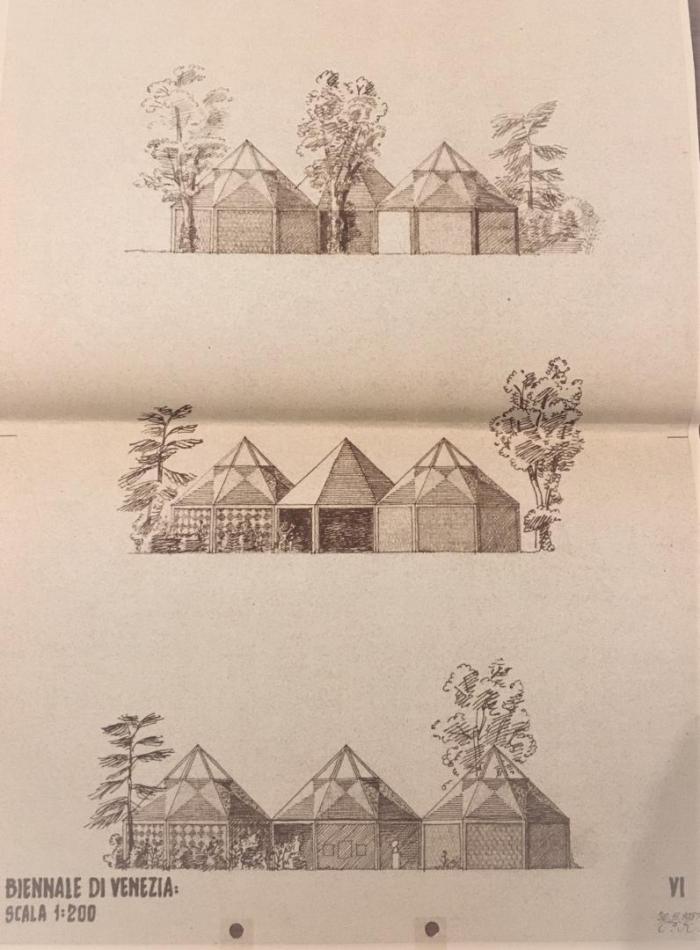

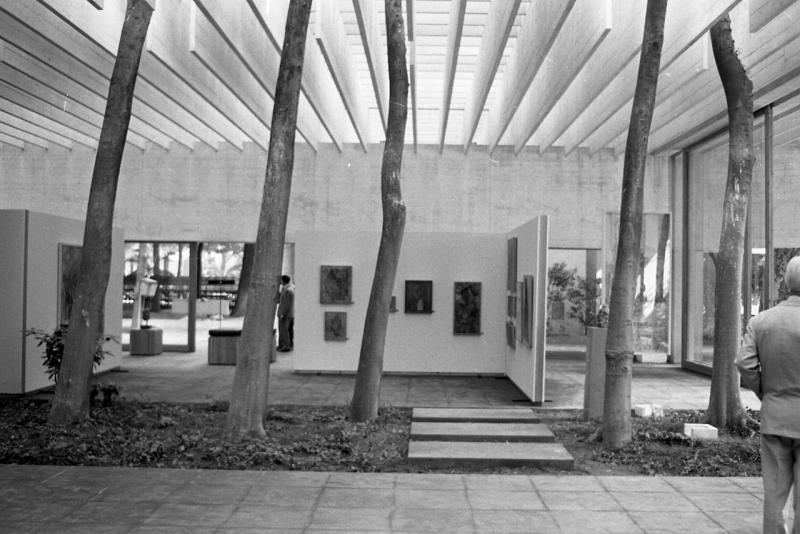

In the 1950s, many advocated the idea of arranging a joint Nordic exhibition in a new, shared pavilion. The suggestion was first put forward in a 1954 newspaper entry by Göran Schildt, who followed the biennial closely and commented on its development and status. Sweden did not have a national pavilion, and according to Schildt, the ideal solution in both economic and ideological terms, would be to have ‘a common Nordic pavilion, which would not need to be much larger than the planned Swedish one, but which would enable the four small Nordic nations to act as cultural superpower at the Biennale’.44 For reference, Schildt was able to point to a current example of successful collaboration on a Scandinavian exhibition: the traveling exhibition Design in Scandinavia, a joint Nordic promotion of furniture design and applied arts which toured the USA in 1954 to 1957. In addition to offering better opportunities for promoting the fine arts, a Nordic pavilion would also be an ‘exponent of architecture’.45 Schildt’s idea resonated with many, and joint Nordic meetings on such potential co-operation were soon held. The increasingly concrete plans resulted in the Danish architect Peter Koch (1905–1980) being asked to draw up a proposal for the pavilion in 1957. His design was based on sections of octagonal pyramid shapes, which would accommodate the individual countries’ exhibitions in a interconnected whole [fig. 7]. However, at a meeting in Stockholm held in February 1958, Denmark nevertheless chose to keep its old pavilion ‘in an improved and expanded form’, thereby delegating the Nordic co-operation to a secondary role.46 Unsurprisingly, this prompted ‘some disappointment’ among the committees of the other Nordic countries47 , who chose to go ahead with the plans for a joint pavilion and issued a competition calling for designs of its architecture. The slightly asymmetrical result materialising in the early 1960s was, therefore, a Nordic pavilion housing Finland, Norway and Sweden, designed by the Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn (1924–2009) and built for the Bienniale in 1962, and a new version of the Danish pavilion with an extension by Peter Koch (1905–1980) inaugurated in 1960 [fig. 8].

The new Danish pavilion was opened in 1960 with a solo show featuring Richard Mortensen. Mortensen, who took part in the 1948 exhibition too, had expressed criticism of Swane’s anti-abstract arrogance48 right back from the time of his involvement with the Linien movement, and in 1948 he called him ‘the kind of dictator associated with days gone past’.49 Since 1948, Mortensen had become one of the most international and in-demand names in Danish art, as is illustrated by his participation in the documenta exhibitions in 1955 and 1959.

True to form, the committee’s choice of artist took place late, and the invitation was sent in March with the exhibition due to open in June. Lars Rostrup Bøyesen acted as commissioner for the exhibition. As stated in a loan application for two works from the Louisiana Museum of Art from 7 June, Rostrup Bøyesen’s had ambitious visions for the exhibition: ‘[Richard Mortensen] will be the only Danish participant, presenting a very substantial retrospective that will fill the entire pavilion, and which we are working to make as strong as possible in the fact of this very fierce international competition’.50

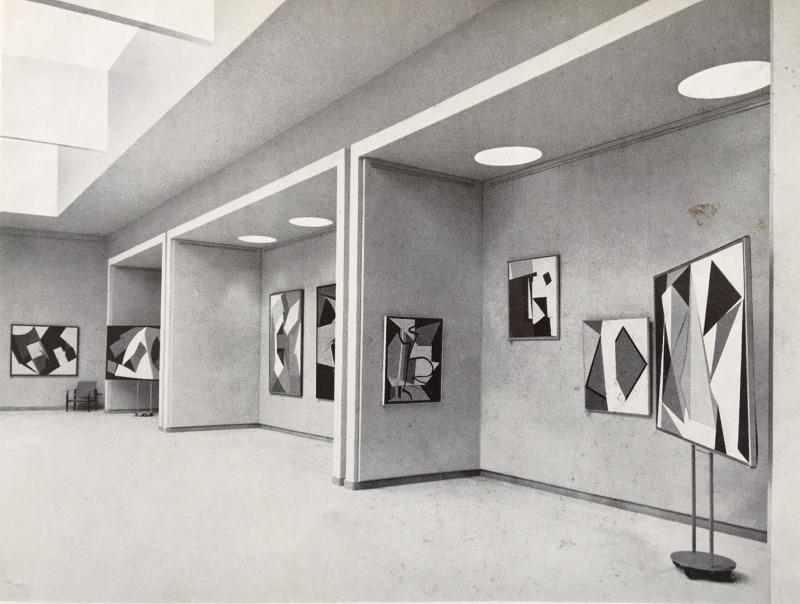

Mortensen himself also took the invitation very seriously, immediately embarking on three large paintings, Aleria, Propriano [fig. 9] and Evisa,51which were displayed as a triptych in the exhibition. Delivered fresh from his Paris studio in May 1960, they testified to his most recent production. – The following year, the works were hung in a similar triptych format at the Frederiksberg City Hall in Denmark and Liljevalchs Konsthall in Stockholm.52 Mortensen created six works to be hung outdoors: these were six new versions of more strictly geometric works from the 1950s done in ripolin paint to adorn the façade of the pavilion [fig. 10]. Inside, the exhibition comprised a selection of eighty works representing twenty-five years of work. A significant aspect of the construction of the exhibition was the use of three niches made of partitions in the old pavilion, forming geometric white cubes around the works [fig. 11].

A catalogue was produced for the exhibition, offering an overview of the artist’s exhibition activity since 1930 and showcasing his international position, asserted by the crowning glory of the 1960 exhibition.53 In the words of the exhibition’s organiser Rostrup Bøyesen, Mortensen had a ‘dual national affiliation’ to both Denmark and France, which meant that Denmark was familiar with his early production, while the more recent work circulated on the international art scene. This was the reason why the Biennale exhibition was subsequently shown at Frederiksberg City Hall in 1961 with reference to ‘the significant international success’ in Venice.54 The reception of the exhibition in Venice was almost unusually positive – and this held true of the exhibition itself and its relationship to the rest of the Biennale’s content. In Politiken, art critic Pierre Lybecker (1921–90) hailed the exhibition as a welcome redress of lost opportunities:

“One remembers with sadness how we have, ever since the war, repeatedly wasted our chances to show the world that Danish painting is a living, breathing, fighting art. Now, we have remedied this state of affairs as far as Richard Mortensen is concerned, and the timing has proven more fortuitous than one dared hope. This retrospective exhibition of his work has turned the ideas held by many of the bienniale’s visitors upside down.”55

Mortensen’s startling effect on the visitors was due to his rejection of the dominant Art Informel. Lybecker regarded Art Informel as the Biennale’s main theme, building on other key exhibitions in e.g. Kassel and Paris, and Lybecker described Mortensen’s exhibition as a ‘liberation from the tyranny of instinct’.56 This is to say that the exhibition came across as autonomous and in keeping with its day, and the general response did not echo the past protests about the shortcomings of the setting.

After the breakthrough – new questions

With the Mortensen exhibition in 1960, Denmark’s participation in Venice had reached a new level of international class. Even popular, low-brow magazines such as Billed-Bladet covered the exhibition, publishing a report headlined ‘Morten’s day in Venice’, which described Mortensen as having ‘become world-famous with a single stroke’, wading in exhibition offerings at this ‘world’s largest painting event’.57 As Swane had already considered after the exhibition in 1948, focusing on a single artist had borne fruit, and here the concerted focus had coincided with a modernised pavilion. It is also worth noting that the show was organised by a dedicated creator of exhibitions, Rostrup Bøyesen, who had been responsible for the majority of SMK’s special exhibitions of modern art by figures such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) in 1957 and Paul Klee (1879–1940) in 1959. While relatively little had written about the Venice Biennale in a Danish context in the past, the early 1960s saw an increase in art criticism’s focus on that exhibition and on the international exhibitions in general.58 Looking beyond newspaper critique, another example is the 1960 yearbook of the prominent Danish museum Louisiana, which contained two reports from the Biennale written by Pierre Lybecker and Gunnar Jespersen. The latter saw the 1960 exhibition as ‘the inner rebellion of abstraction’ between the Expressive and the Concrete camps with Mortensen as a handy intermediary.59 In the newly launched art journal Signum, presented the following year as a new Danish art magazine focusing on modern art and international perspectives, the author Ole Sarvig (1921–81) contributed an article called ‘Venedigs mudrede spejl. Biennalen 1960’ (The Muddied Mirror of Venice. The 1960 Biennale, 1961), offering an extensive analytical panoramic view of the Biennale. He noted the Biennale’s ability to reinstate the pioneers of Modernism, whereas contemporary art was dominated by an Expressive fascination with doom and gloom as ‘a desperate final act in the spirit of Surrealism and anti-art’, while at the Danish pavilion Mortensen ‘holds the fort alone, if somewhat distractedly, for Vasarely, Magnelli and himself with his colourful and highly decorative concretions’.60

Building on the success of the Mortensen exhibition, but also on the problems associated with the Danish pavilion, Signum once again focused on the Danish presence in Venice with a survey feature on ‘Denmark at the Biennale’ (1961).61 Here, a number of key stakeholders – Folmer Bendtsen (1907–93), Victor Brockdorff (1911–92), Erik Fischer, Asger Jorn, Erik Poulsen (1928–99) and Ole Sarvig – were asked to assess Denmark’s opportunities ‘as they have been utilised so far and how they might be utilised in the future’.62 In the responses, Denmark’s participation since 1945 was described as having been characterised by shortcomings, both in the selection and the execution, which Bendtsen described as ‘paltry and cheap’. Sarvig saw things as having been particularly bad during ‘Leo Swane’s strange regime’, making the following comment on the 1948 exhibition: ‘People truly believed that they had entered the Biennale’s lumber room and hurriedly withdrew with many apologies’.63

However, much had improved with the last two exhibitions in 1958 and 1960, where it was said that ‘the presentation of graphic arts was exemplary and the Mortensen exhibition justified’ (Sarvig), and that ‘Danish artists have hardly presented themselves to better advantage than in the last two exhibitions’ (Fischer). By contrast, Jorn believed that the Biennale had entirely lost its relevance and could only become relevant through a change in cultural life. As regards the central purpose of participating in the Biennale, artistic quality was particularly emphasised, while the respondents had different views on the question of international orientation. Bendtsen spoke in favour of highlighting national distinctiveness ‘by placing the main emphasis on the distinctive – in the best sense of the term – national traits we undoubtedly have in Denmark and in the other Nordic countries, without looking overly much to fashionable international currents’ (which was close to the committee’s line during Swane’s regime), while Fischer advocating efforts to ‘show a larger public how Danish artists work’ by presenting profiles such as Mortensen, who could then be followed by Jorn and Carl-Henning Pedersen.

No less interestingly, the survey was followed up by Rostrup Bøyesen in the next issue of Signum with a longer entry about Denmark’s participation, ‘Biennale-Problems’ (1961).64 Even though Rostrup Bøyesen found parts of the Biennale problematic – such as the over-representation of the host nation, the dubious awarding of prizes and the battle for attention – he believed that it was important for Denmark to participate – and do it right: ‘So far we have weakened our own position by basing our choices too much on a Danish outlook and too little on an international one’, he opined, referring to the many names from the 1942 Biennale as an example of ‘Biennale suicide’ – albeit without commenting on the special circumstances applying to this particular instalment. He also believed that the selection committee was too much influenced by local conditions and ought to be changed, and that it was necessary to invest at least a bare minimum in PR and representation, as well as to set aside more time for the organisation of the exhibition than the few months he himself had recently been allowed to set up the Mortensen exhibition. Being a commissioner and co-organiser, Rostrup Bøyesen spoke from personal experience, and he summed up his solution to the ‘Biennale problems’ as follows: ‘by selecting its representatives according to an international rather than a local scale, by setting aside a relatively affordable extra sum for reasonable propaganda and by allowing itself ample time for planning and processing, Denmark would give itself significant advantages in terms of asserting itself in the tough race of the Biennale’.65

In this discussion on the Biennale, the external critics and the internal organiser evince a general agreement on the challenges and ongoing developments. The demand for renewal entailed a confrontation with the old ideas, dating back to Swane’s time, that the national presentation ought to consist of a historical, representative selection of particularly ‘Danish’ artists. Now, they found themselves occupying a central juncture in the history of the modern art exhibition and had to respond to its new demands for investment and commitment, making it necessary to instead make one’s selections according to ‘international rather than local standards’.

Success in the 1960s

Up through the first half of the 1960s, the Biennales saw a successful and stylish sequence of Danish contributions: from Mortensens confident assertion in 1960 to the exhibition in 1962 featuring Carl-Henning Pedersen and Henry Heerup (1907–93), with the former receiving the exhibition’s UNESCO award; to 1964 with Svend Wiig-Hansen and 1966 with Robert Jacobsen (1912–93), who received the exhibition’s grand prize for sculpture. During the period, Denmark stuck to its plan of focusing on a single artist who fit the parameters of international abstraction with a clear emphasis on spontaneous expressiveness. In an article on ‘Impressions from the Biennale and Documenta’ in Louisiana Revy, the Swedish critic Kristian Romare described the Danish pavilion as being characterised by ‘razor-sharp choices and generous presentation’.66 Here, Romare praises the Danish execution over the rather more muddled Nordic pavilion: ‘Denmark has stayed true to its adopted line, while its neighbours in the Scandinavian pavilion are stuck in compromises that involve many names and flimsy collections. We must find a way away from these half measures if the Nordic region’s participation in Venice is to have any real heft as a whole’.67 By this point, in 1964, the Danish pavilion was seen as being executed with far more professionalism and stylistic flair than the ‘tepid middle ground’68 seen ten years previously.

The Danish art world had indeed become significantly more international in its outlook and better geared towards exhibitions, with Louisiana as the centre and forum for the latest artistic experiments. Notably, the 1962 Biennale exhibition featuring Pedersen and Heerup had its dress rehearsal at Louisiana before being sent to Venice. In an interview with Mortensen in B.T. in 1960, one writer described the new Danish pavilion as ‘a smaller version of Louisiana, a Venetian version of Louisiana’69 with trees and flat brick buildings. It is tempting to see the post-war history of the pavilion as a movement away from the SMK to Louisiana: at the beginning, the exhibitions were museum-like, aiming for an all-round representation set within a classicist pavilion, and then gradually transitioned towards a format more akin to the modern art museum’s special exhibitions aimed at the here and now, set within an architectural framework to match – a lesson that could have been taken on board in connection with SMK’s reopening after a year-long renovation in 1970. However, SMK continued to distance itself from an overly outgoing and contemporary profile, a role which they believed to be covered by Louisiana. One must, however, include the caveat that Louisiana was never formally in charge of the Danish pavilion. Instead, Louisiana had close contacts with the documenta organisation, and in 1960 they showed the exhibition Vitalita nell’Arte (Vitality in Art), previously shown at the Palazzo Grassi as a kind of competitor to the Biennale.70

In recent years, a number of studies have shed new light on the reconfiguration of the European art world after 1945. According to art historian Catherine Dossin, increased mobility and internationalisation were important driving forces behind the artistic and institutional activities alike.71 The international exhibitions played a key role in this regard. Austrian art historian Nuit Banai describes how, after 1945, the European nations – especially Germany and Italy – were in the process of being reborn as ‘post-national’, a trait measured by their ability to be international.72 In the post-war period, Denmark did not face the same issues of discredited and traumatic self-confrontation, but still had to redefine itself in an international, pan-European direction, both politically and culturally. Ideas of neutrality and a planned Nordic collaboration on military defence had to be abandoned under the pressure of the Cold War, with Denmark joining the rest of Western Europe in the North Atlantic Treaty at the same time as the restarted Biennale – it seemed better to voluntarily be part of the Free World’s attractive internationalism than to be coerced into participating on the terms of an occupying force, as Denmark had only too recently learned.

As has previously been mentioned, art historian Caroline A. Jones has analysed the Biennale as the wellspring of the international artist and of a desire for the global as the common denominator of the Biennale’s participants and organisers. Jones encapsulates this in the concept of Biennial Culture, the core of which is to generate art as an experience encapsulated by the exhibition format.73 The exhibitions in the Danish pavilion evince a gradual adaptation to Biennial Culture and the shift towards greater internationalisation. This proved successful with Mortensen in 1960, and momentum was maintained at the following exhibitions. The production of the international artist was not without its costs, with Nordic co-operation having to give way to the ‘razor-sharp choices’ of individual artists. It should also be noted that no women artists were among these ‘razor-sharp’ selections, and that the artists’ associations slipped into the background too.

1968: The last Biennale?

The momentum achieved by the Danish organisers’ amended approach to their Biennale exhibitions did not last very long; soon, they were once again overtaken by realities. Overall, the view of the Biennale as an international locus capable of embracing and encapsulating contemporaneity saw a slow decline in the 1960s. In 1962, Pontus Hultén (1924–2006) – an eager arranger of exhibitions and the director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm – stated in the Louisiana Revy that the Biennale was big rather than beautiful, ‘a little old-fashioned’, and ‘far from being the presentation of what is going on around the world that it purports to be’.74 Hultén himself sought to turn the Moderna Museet into a dynamic platform for contemporary art and its avant-garde roots, actively involving visitors through total installations, performances and interactive works. Viewed from this position, the Venice Biennale seemed stale, static and inadequate. In 1968, Berlingske Tidende’s art critic, Ejgil Nikolajsen called the Biennale ‘a dying swan’, stating that: ‘what Venice shows regarding the more general tendencies and symptoms of contemporary arts are merely parts of an already familiar pattern, often seen illuminated to more significant effect at other exhibitions such as documenta in Kassel or, regularly, in venues no further afield than Humlebæk [the Louisiana museum] (and at Den Frie and KE [The Artists’ Autumn Exhibition])’.75 The biennial was being overtaken by a more widespread boom in exhibition activity, one that also extended to the new museums such as Louisiana and the Moderna Museet.

In 1968, the year of youth revolts [fig. 12], the Biennale was the scene of protests, occupied pavilions and clashes between protesters and police, reinforcing the general perception that this was an exhibition allied with the reactionaries. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the Danish committee had, in 1967, invited Asger Jorn to exhibit at the Biennale in 1968, an offer he immediately rejected.76 The committee, with Rostrup Bøyesen as commissioner, went on to choose Mogens Balle (1921–88) and Frede Christoffersen (1919–87) instead, thereby continuing along the Abstract Expressionist lines as before, but this no longer had the same impact. In the wake of this chaotic Biennale, Rostrup Bøyesen published a paper on the history of the Venice Biennale with particular focus on Denmark’s participation.77 His account is not least noteworthy due to his deliberations on the Biennale’s continued existence after the events of 1968, which made it ‘the strangest Biennale’78 in history, ending with the words: ‘Was the 1968 Biennale the 3479 and last of the series, or does it have some future ahead of it, whether limping or luminous? Qui vivra verra’.80 As the reader will be aware, the Biennale did not meet its demise; rather, it was revitalised as the centre of a global vein of contemporary art characterised by biennialisation81. The same has been true of art museums, which might also well have been seen as obsolete and surplus to requirements in the eyes of the ’68 generation.

In this article, I have aimed to provide a nuanced picture of the international Biennale during a time of transition – one to which its participants tried to adapt, thereby prompting the rise of the contemporary art exhibition as we know it today; a development that would also have a considerable impact on the museums.

As has been demonstrated, the Venice Biennale took on new significance after 1945, acting as a litmus test for the production of the international artist and the successful exhibition. This created a special relationship between the national and the international at a time when both of these entities were seeing new development and involved new openings as well as the drawing up of clear boundaries. From representing the art scene of one’s homeland (in the version favoured by its most powerful men) and the curious cultural diplomacy of the war years, there was a more or less deliberate steering towards an increasing internationalisation, an approach which proved successful for a number of years, but was then thwarted by unforeseen events. Such a situation seems familiar to us in the year 2021 as we continue to see upcoming exhibition events surrounded by post-pandemic uncertainty.