Summary

Christine Deichmann (1869–1945) is among those artists who seem to have fallen through the cracks of Danish art history writing, where her achievements as a woman artist and as a resident of Greenland have been largely overlooked and forgotten. In her capacity as an artist travelling to and in Greenland, she is part of a long line of Danish artists who have ventured abroad to find inspiration and subject matter in places and cultures that seemed ‘foreign’ to them. Among these, Deichmann is unusual in her choice to depict women and children in an intimate, introspective space, absorbed and engrossed in their tasks; a choice that went against the grain of the era’s prevalent colonial gaze on the Greenlandic landscape and people. Having said that, she remained a Danish artist in Greenland, a position full of colonial implications. In order to unfold this dual perspective on Deichmann’s practice and works, we will look at her in light of the constrictions and conditions applying to her due to her gender in her own day, and we will also consider her art against the backdrop of a necessary, critical scrutiny of Danish art history writing’s conspicuous absence of artists who travelled to and in Greenland.

Articles

A curatorial and methodological starting point

The present article is primarily based on archival studies, reflections and analyses carried out in connection with years of curatorial work focusing on Danish artists in Greenland, as seen in Danish and Greenlandic contexts alike. This work takes its starting point in the collection at Nuuk Art Museum1 (NK), in the preparations for the exhibition Nulialo//And Wife (5 February – 21 March 2021) at NK, and in the upcoming exhibition You Gaze On Me – as I Gaze Upon You at Nordatlantens Brygge/North Atlantic House, which will open in October 2024.2 The exhibition Nulialo//And Wife focused on the artists Christine Deichmann, Ellen Locher Thalbitzer (1883–1956) and Oda Isbrand (1904–1987), who all set out for Greenland before 1940. All three were accompanying their husbands who had professional reasons for coming to Greenland. At the exhibition You Gaze On Me – as I Gaze Upon You in 2024, those three artists are presented alongside Emilie Demant Hatt (1873–1958) and Jette Bang (1914–1964). All five share a kinship by being Danish artists – and women – who visited Greenland before 1940.3

In Denmark, artworks depicting Greenlandic subjects by artists who travelled to Greenland are largely absent from art collections; they are primarily found in collections dedicated to cultural history instead. Having been more or less written out of Danish art history, such scenes of – and gazes upon – Greenland are rarely treated as artistic constructs embedded in a specific tradition and time, and as a consequence the colonial context of such artworks is not challenged. This issue is addressed and problematised by Mathias Danbolt et al. from the academic network The Art of Nordic Colonialism – Writing Transcultural Art Histories,4 for example through the lens of visual anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards’s concept of ‘elsewhere’, which points out ‘how colonial history has been disconnected from the narratives one meets in northern European museums in particular, to instead be relegated to other geographies, other historical eras and other disciplines (such as anthropology).’5 However, it should be added that the past ten years have seen a resurgence in curatorial and academic interest in artists who have visited Greenland, resulting in a range of art exhibitions, MA theses and research articles on which this article partly relies.6

Thus, the present article dovetails with an ongoing dialogue about the decolonisation of the art history discipline. Scholar Eve Tuck and professor K. Wayne Yang state that decolonisation is not a metaphor we can apply to all places at all times, as decolonisation requires that the multifaceted narratives and structures of colonialism be made visible. Taking their starting point in the question of what colonialism is, as posed by author and politician Aime Cesaire, they write:

Because colonialism is comprised of global and historical relations, Cesaire’s question must be considered globally and historically. However, it cannot be reduced to a global answer, nor a historical answer. To do so is to use colonisation metaphorically. ‘What is colonisation?’ must be answered specifically, with attention to the colonial apparatus that is assembled to order the relationships between particular peoples, countries, the ‘natural world’, and ‘civilisation’. Colonialism is marked by its specialisations.7

In this sense, this article constitutes an effort to foreground a specific period and a selection of artists, particularly Christine Deichmann, who are almost all absent from art museums and art historical contexts in Denmark, which in turn reflects an absence of colonial history(-ies) within the art history discipline in Denmark. Raising a point pertinent to this discussion, Yale University professor Tim Barringer states that the very concept of decolonising art history rests on a misconception: ‘Art history can decolonise itself only to the extent that it acknowledges that Euro-colonial art and our discipline itself are themselves products of empire.’8 The raison d’être for the present article is that by shedding light on a number of the many-sided and specific narratives of colonialism in a Danish-Greenlandic context found within the art history discipline in Denmark, we can make visible the underlying structures of which those narratives are manifestations – including their significance for society today. As Barringer goes on to say about the art historian’s role in a decolonisation process:

We can formulate critiques of art-historical legacies and lexicons, and of colonialism itself as manifested in the visual and material. Art history can and must take a critical approach to empire and colonialism, and can use the privileges of its position to undermine the assumptions implicit in an imperial subject position.9

Based on the dual question: Under what historical conditions did the forgotten/overlooked artist Christine Deichmann’s (1868–1945) create her artworks representing Greenlandic subject matter, and what distinguishes her position compared to the male artists travelling to and in Greenland during the same period?, we want to address, problematise and probe the marginalisation (and re-inscribing) of Danish artists in Greenland 1870–1940 in Danish art history. We do this in order to reflect and deconstruct these artists’ outsider’s views of Greenland; gazes which in many ways reach all the way up through time to our present day.

More than forty years ago, art historians Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock emphasised the point that the very structure on which we build our art historical narratives must be challenged in order to (re)inscribe marginalised (women) artists. This is not a question of integrating or annexing the forgotten/overlooked artists into the existing body of art history writing, but rather of approaching artists and their art based on the historical conditions under which the works were created and of which their practice was a part.10

In this article, we have chosen to outline the circumstances and framework surrounding Christine Deichmann by first offering a presentation of Danish artists travelling to Greenland with a focus on Deichmann’s male colleagues and the images of landscapes and folk life they predominantly created. We place them within a Danish art historical context that also harks back to the travels and grand tours of Danish Golden Age artists. We then turn to Deichmann and examine how her choices of subject matter contrast with those of her male fellow travellers to Greenland, partly due to Deichmann’s position as a woman artist in Denmark and as a spouse accompanying her husband to Greenland. To establish the backdrop for this, we will consider aspects such as Deichmann’s education and her participation in exhibitions, and we will explore parallels between Deichmann and fellow women artists in Denmark and Greenland, among them Anna Ancher and Ellen Locher Thalbitzer. All this serves to ultimately posit Deichmann’s artistic work as a complex duality: her art challenged the period’s colonial views of the Greenlandic landscape and people, and at the same time she was a Danish artist in Greenland with all the colonial implications inherent in such a position.

(Male) Danish artists in Greenland

Christine Deichmann moved to Greenland in 1901, making her, as far as is currently known, the first Danish artist in Greenland who was a woman. The years 1870–1940 saw an increasing influx of Danish artists travelling to Greenland, bringing along their canvases and brushes. Some were part of the official Danish expeditions, others travelled on their own.11 The period was dominated by male artists who go by monikers such as ‘Grønlandsmalere’, meaning ‘Greenland Painters’. A term whose origin is unknown12, but which in European exhibition contexts has been used to describe Danish male artists who travelled to and found inspiration and subject matter in Greenland during the period 1870 to the 1940s. The ‘Greenland Painters’ are not a movement, a group or an artists’ colony, but rather a designation used about individual artists who applied different styles and were rooted in different times.13 ‘Expedition art’ is another term often used in this context, denoting (male) artists associated with the Danish scientific expeditions14 where the artworks created and the subject matter depicted were all part of a scientific, colonial project intended to gather knowledge about and create records of Greenland in different ways. The Greenland Painters and expedition artists exhibited at the established Danish art scene of the time, including at the juried academy exhibitions at Charlottenborg, as well as at the various World’s Fairs, colonial exhibitions and Greenland Exhibitions of the period.15 At the latter platforms, artworks featuring scenes from Greenland were placed in an ethnographic context, representing Danish-colonial views of Greenland. For example, this held true of the Greenland Painter Jens Erik Carl Rasmussen’s (1841–1893) A Stretch of Coast in Greenland. Midnight, 1872, which was bought by the Royal Collection of Paintings (later Statens Museum for Kunst, SMK). The work was the first painting in the SMK collection to depict Greenland, and it was exhibited at venues such as the world’s fairs in Paris in 1878, in Chicago in 1893 and at the International Colonial Exposition in Paris in 1931. In 2023, the work was added to SMK’s range of works on permanent display; as yet, it is the only scene from Greenland created by one of the Danish visiting artists addressed in this article to have achieved this status.16 A Stretch of Coast in Greenland. Midnight is one of the first works to show the kind of subject matter that would later become typical of expedition art and the Greenland Painters: landscape paintings showing magnificent natural scenery and/or depictions of folk life with more or less Romantic images of Greenlanders/Inuit in arctic scenery.17 Other examples can be found in the oeuvre of the Greenland Painter Emanuel A. Petersen (1894–1948), whose work was also shown at the colonial exhibitions in Paris and in Rome in 1931.18

A great paradox concerning these works is that while the Greenland Painters and expedition artists appear to be unknown or overlooked in Danish art history, virtually everyone in Greenland knows these images. They hang in people’s homes and virtually colonise, in copious numbers, not only the cultural history museums but also the two Greenlandic art museums in Greenland,19 several of which museums were set up by or at the instigation of Danes.20 At the same time, many of the landscape images evoke a sense of local recognition. Former director of the Ilulissat Art Museum, Ole Gamst Pedersen, explains the phenomenon using Emanuel A. Petersen’s paintings as an example:

Most of the tourists have long since fallen thoroughly in love with Greenland, and they swallow Emanuel A. Petersen’s romantic scenes of Greenland hook, line and sinker, with no reservations whatsoever. While we ourselves, here in Greenland, often take a more pragmatic approach to Emanuel’s pictures. For example, this might manifest in comments such as: ‘Oh, I know that location; I went there when I visited my wife’s family ten years ago.’21

On the one hand, Gamst Pedersen here reaffirms how such scenes represent the gazes upon Greenland that tourists swallow whole (and are eager to see/apply themselves); on the other hand he points to the element of recognition being the most essential aspect for locals, something we have also found to be the case at the Nuuk Art Museum.

The work of photographer Jette Bang can be seen in this light, too, as accounted for by the author behind a monograph about Jette Bang, Leise Johnsen (former head of the Nordic Institute in Greenland and current head of the Greenlandic House in Copenhagen) in an article in the art and culture journal Neriusaaq: here Johnsen addresses how Bang’s photographs first and foremost prompt recognition of people and places.22 Professor of Sámi culture Veli-Pekka Lehtola points out similar issues of recognition pertaining to archived photographs of the Sámi, which are most often perceived by the Sámi themselves as part of a narrative about our stories rather than being seen as part of a wider colonial and external narrative:

The Sámi themselves approach the archival photographs often from the community perspectives, revealing ‘small stories’ of us and our ancestors rather than ‘big histories’ of colonial circumstances and contradictions with outsiders’ societies.23

In Greenland, landscapes also constitute the subject of paintings created by a number of Greenlandic artists in the first half of the twentieth century, such as Steffen Møller (1882–1909), Peter Rosing (1892–1965), Otto Rosing (1896–1965) and Henrik Lund (1875–1945). As had been pointed out by associate professor at the University of Copenhagen Kirsten Thisted, in the 1930s the writer and artist Hans Lynge and the authors Frederik Nielsen (1905–1991) and Pavia Petersen (1904–1943), drawing inspiration from Danish Golden Age art, began to see the Greenlandic landscape as a natural element of an overall effort to strengthen Greenlandic identity and national feeling.24 The Greenlandic landscape painters inscribe themselves as part of this moment. From the 1970s onwards, one finds several critical voices on the Greenlandic contemporary art scene that specifically problematise the gazes associated with expeditions and colonisations – including representations of landscapes. A lithograph called De rejste og rejste (They Travelled and Travelled) from 197925 by artist Anne-Birthe Hove (1951–2012) offers a simultaneously humorous, reflective and bitingly critical depiction of (European) scientists brandishing various equipment within a small area, measuring and naming things, while a (Greenlandic) man by a fire and a woman bent over a seal or fish are placed out to one side and in the background, a lot of bones in front of them. Incidentally, depictions of a man and a woman around a fire with the woman in this characteristic bending position is a recurring motif in, for example, the work of the Greenland Painter Emanuel A. Petersen.

The forgotten Greenland journeys as a continuation of nineteenth-century travels

In their letters and diaries, the male Danish artists travelling to and in Greenland were generally critical of the colony and the so-called modernisation taking place there. Several of them speak of a Greenland about to be lost: they strive to capture this lost land and so preserve it for posterity. It goes without saying that applying such a gaze to landscapes and people – and having that kind of longing to experience and portray the ‘authentic’ and ‘original’ – influenced these artists’ perception of what they saw. The Greenland Painters and expedition artists most often left out all textiles, objects and machines that did not seem ‘original’ to them. According to art historian Karina Lykke Grand, something similar held true in the Danish Golden Age. The travelling artists of this period, which roughly corresponds to the Romantic era, showed pictures of ‘lush local folk life, picturesque ancient ruins, magnificent temples, beautiful mountain peaks and sun-drenched bays with local fishermen.’26 Such idealising depictions stood in stark contrast to the artists’ own travelogues and other written sources, which paint a picture of a very different Italy: a country full of tourists and rapid developments. Deliberately seeking out ‘foreign’ subject matter can also be seen as a criticism of the Europe from which the artists came. As art historian Alena Marchwinski writes, during the Danish Golden Age the orient came to serve

as a reflection of the Europeans’ own dreams and needs and even as an implicit critical commentary on Western civilisation. The European observer, wearied by civilisation, projects onto the image of the Orient his longing for a lost past with all that this might have entailed in terms of adventure and freedom of expression.27

The Danish artists visiting Greenland voiced a similar weariness with civilisation. J.E.C. Rasmussen articulates such views in a letter to his fiancée written in 1872, recollecting Greenland from Paris:

When, like me, one has seen the grand, elevated, pure Greenlandic nature and felt closer to the Creator, and done so in moments when one seemed to be lifted up above the Earth and away from the petty struggles of civilised life, then it becomes exceedingly difficult to enter an enraptured state of ecstasy at sights such as the one I saw the other day at Montmartre, seeing the whole of Paris half hidden by fumes from its gutters and stove, joining the endless smoke and dust that hangs over the entire city, whatever the weather.28

Such civilisation fatigue or critique is also connected to the wider European debates on colonial issues seen in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Danish colonial authorities were keenly interested in the question of whether the civilisation process had gone too far. Knowledge gathered from various sources, including expeditions, was used to level criticism against the colonies and how they were managed. The expression the white man’s burden became widely used among the European colonial states, denoting ‘the feeling that you owed the peoples you had colonised to help them grow in numbers, prosperity and civilisation.’29 The nations further discussed ‘the seeming inability of indigenous people to survive the encounter with Western civilisation’s individualism, perception of property rights and free market economy.’30 In Denmark, this led to the conclusion that the Greenlanders should be protected from being overwhelmed by too many features of Western civilisation, and the colonial policy of the nineteenth century was based on the principle that the Greenlanders should constitute a nation of sealers.31

As was the case for other travelling artists of the nineteenth century, all of the artworks created by the artists who visited Greenland were aimed at European exhibitions and an increasingly affluent European middle class. This contributed to establishing the parameters for the ‘foreignness’ of the subjects depicted. For example, Marchwinski describes how the middle classes – the bourgeois subject – took an interest in all that seemed in their eyes titillating, unusual and different and how they sought, by way of comparison, to ‘define and highlight their own national identity.’32 The world’s fairs, colonial expositions and Greenland exhibitions were not just displays of art and objects; they were also part of a geopolitical game between the colonial powers. During the so-called age of imperialism from 1884 to 1945, the scientific expeditions were driven by the European colonial powers’ need for knowledge about geographical conditions, about natural resources and raw materials as well as about the local populations, which had to be understood in order to be controlled.33 But as head of research and collections Christian Sune Pedersen and curator Jesper Kurt-Nielsen at the National Museum of Denmark state, the expeditions in particular cultivated a view of culture based on ‘the notion of the authentic as a kind of immutability: a culture that had always been there until European modernity swept across the world.’34 But, they add, ‘what these expeditions with their scientific ballast tended to overlook was that culture and cultures are dynamic quantities […] most often informed by previous cultural encounters, migrations and technological developments.’35

Christine Deichmann: Overlooked ‘Modernity’

Christine Deichmann was part of this era, but her works nevertheless – and unusually – include imported textiles and objects in their depictions of scenes from Greenland. These textiles and objects reflect a ‘modernity’ which in fact dated back several hundred years. Christine Deichmann did not paint sublime, harsh and desolate landscapes or Greenlanders/Inuit clad in traditional costumes; rather, she painted women and children in everyday clothes, and here European textiles and fashion were mixed with leather and fur clothing. With this move, her works offer a different view of Greenland, one that can potentially problematise and deconstruct her (male) contemporaries’ gaze upon Greenland and Greenlanders/Inuit; a gaze which, to a present-day observer, still contributes to reproducing a narrative about Greenland that focuses on overwhelmingly sublime nature, ‘untouched’ wildernesses and (European) concepts of the original.36

Like her male fellow artists, Deichmann exhibited at the Grønlandsudstillingen (Greenland Exhibition) in Copenhagen 1921 and at the Colonial Exhibition in Rome in 1931. In these exhibitions, Deichmann’s works contributed to shaping European views of Greenland as a country and the Greenlanders as a people, and in that sense her art formed part of Denmark’s continued colonisation and struggle for the right to Greenland. According to the list of works for the great Greenland Exhibition held in 1921 in Nikolaj Church in Copenhagen, Deichmann exhibited twenty-seven works; as many as the expedition painter Aage Bertelsen (1873–1945) and surpassed in number only by the expedition painter Harald Moltke (1871–1960). Notably, the majority among those of Deichmann’s exhibited works that depict people have titles such as Young Girl, Alibak, Old Marie and The Breadwinner.37 Particular attention should be paid to the fact that, except for one work, the titles almost never refer to the people depicted as ‘Greenlanders’, which was otherwise customary at the time. Instead, the artist uses names or other designations. Secondly, the choice to focus on people at all appears to be unusual compared to the other paintings in the exhibition, which, judging from the titles, were mostly landscapes. The few among Deichmann’s works at the exhibition that did in fact feature landscapes had been forwarded at a later date because Deichmann’s daughter had informed her that the exhibition committee wanted more Greenlandic landscapes.38 In what follows, we will discuss how, in Deichmann’s works, we see glimpses of a gaze other than that which we have so far described as dominant among the expedition artists and the Greenland Painters. First, however, we will provide a brief introduction to Deichmann’s endeavours as an artist.

The artist Christine Deichmann

Christine Deichmann left only few art historical traces for us to follow. We know that Deichmann took lessons from the artists Frederik Rohde (1816–1886), Simon Simonsen (1848–1921) and at Vilhelmine Bang’s School of Drawing before going on to attend the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1891–94, studying at the academy’s then very recently opened school for women. From 1896 to 1912, Deichmann exhibited regularly at the annual juried Spring Exhibition at Charlottenborg, and in 1907 she exhibited at the Artists’ Autumn Exhibition at the same venue. Together with her husband, Henrik Deichmann (1871–1939), and their daughter, Elisabeth Deichmann (1896–1975), she lived in Greenland from 1901 to 1910. Henrik Deichmann worked as a doctor, first in Qaqortoq (then called Julianehaab), then in Sisimiut (then called Holsteinsborg). Deichmann also exhibited at Kvindelige Kunstneres Retrospektive Udstilling (Women Artists’ Retrospective Exhibition) in 1920 and at the aforementioned Greenland Exhibition in Nikolaj Church in 1921 as well as at the Colonial Exposition in Rome in 1931. After Christine Deichmann’s death in 1945, her daughter Elisabeth Deichmann arranged a memorial exhibition in 1947.

As far as Danish museum collections are concerned, Christine Deichmann is represented at Kunsten Museum of Modern Art in Aalborg (two original watercolours), Vardemuseerne (not a work related to Greenland), Museum VEST (a reproduction of drawing) and M/S Maritime Museum of Denmark (original drawing). The Danish Arctic Institute also owns a number of reproductions of Deichmann’s drawings and watercolours, as well as a number of photographs by Christine Deichmann.39 Turning to Greenlandic museum collections, the Nuuk Art Museum owns two works by Christine Deichmann, but the largest collection of Deichmann’s works on Greenlandic soil is found at Nunatta Katersugaasivia Allagaateqarfialu/Greenland National Museum and Archives (NKA). The latter collection was donated to what was then Landsmuseet in the 1960s by her daughter Elisabeth Deichmann, with a further donation made by Radcliffe College, Massachusetts, USA in 1998.40 This article takes its starting point in the works from the two museum collections in Greenland, focusing particularly on depictions of women and children. Christine Deichmann personally highlighted such subjects as especially characteristic of her art.41 Some of these images remain well known in Greenland today: when Deichmann’s works were donated to the NKA in the 1960s, a range of postcards and posters were printed to help raise funds for a kindergarten in Nuuk. In 1978, a new range of postcards of works that had not previously been reproduced was issued, this time in aid of an expansion of the Knud Rasmussen Folk High School and of the school’s work with young people. In addition, in 1999 the NKA presented an exhibition showcasing their collection of Deichmann’s works. Deichmann’s pictures can still be found on postcards and posters sold in Greenland and are now more generally known in a Greenlandic than in a Danish context. As we have touched upon in connection with the works of photographer Jette Bang and the Greenland Painter Emanuel A. Petersen, Deichmann’s images generally evoke a response of recognition in Greenland, rather than being seen as part of a wider colonial narrative imposed from above.

Accompanying wife

In her submission for her entry in Weilbachs Kunstnerleksikon (Weilbach’s Biographical Dictionary of Artists), Christine Deichmann herself highlighted her ‘Greenlandic figure scenes, particularly those of women and children’;42 subjects that had received scant attention from the other (male) Danish artists in Greenland. In work after work, sketch after sketch, Deichmann shows women and children occupied with chores in spaces that are indistinct, almost blurred. It would appear that the main point here is not to depict the exact nature of what they are doing; rather, the emphasis is on the general act of concentrating on something and being absorbed in it. As viewers, we get a clear sense of looking in on these scenes from the outside, and at the same time we feel the artist’s deep fascination with what is being depicted. One perceives Deichmann’s urge to capture and record the intimate space occupied by those she depicts, but also a fascination with portraying another culture, one to which she, being a Danish woman in Greenland, has only limited access. Deichmann was not in Greenland to settle permanently, rather, the Deichmann family could be regarded as posted labour. It should be added that although some Danes settled and stayed, Greenland was not a settlement colony per se; rather, the main objectives were ‘trade’43 and missionary work. Having said all this, Deichmann was a resident of Greenland for nine years, which gave her access to these everyday spaces occupied by women and children. At the same time, her everyday life as the doctor’s wife was different from that of many Greenlanders. Being the wife of a doctor, Deichmann was part of the Danish colony set-up and bourgeoisie in Greenland. Within the colonial administration, marriages were regulated by contracts and prohibitions right from the early stages of the colonisation era. In 1782, a ban on mixed marriages was introduced. Concurrently with this, those with the highest-ranking positions within the trade sector were given the opportunity to bring their Danish wives and any children with them to Greenland, and from the 1820s onwards the number of wives and children accompanying the head of their family grew.44 The European wives served as a kind of ‘moral bulwark against relations between Danish men and Greenlandic women.’45 Dalliances between the colony’s top Danish officials and Greenlanders was considered problematic because ‘it blurred the boundaries and balance of power between Europeans and Greenlanders necessary to maintain the social order of the colonial project.’46 The arrival of accompanying wives and children meant that over the course of the nineteenth century, a Danish bourgeoisie arose in the colonial towns; an upper class of Danish homes and Danish families who primarily socialised with other Danish families.47 In her capacity as a doctor’s wife, Christine Deichmann entered this community; for example, her daughter was home-schooled alongside the only other Danish-speaking child in the colonial town.48 The divide between Danish and Greenlandic everyday life was also emphasised many years later by the artist’s daughter, Elisabeth Deichmann, in a letter in which she describes a girl whom Christine Deichmann used as a model: ‘we called her the “Family breadwinner” because she essentially kept her old grandmother alive on what she earned by being a model for my mother.’49 Elisabeth Deichmann does not mention the little girl’s name, even though they were both children in the same small town at the time. In being called the ‘family breadwinner’, the girl is first and foremost seen as a paid model for the writer’s mother, accentuating the unequal nature of their relationship. As a Danish doctor’s wife, Deichmann had a position which required her to observe certain niceties of etiquette to uphold the distinction between coloniser and the colonised. Had she been in Denmark, her position would require her to socialise only with a particular type of people. From a practical point of view, sticking to such a restricted social circle was difficult in Greenland, as only very few people in each town belonged to this bourgeois class. So on the one hand, she was on a footing of ‘everyday intimacy’ with the people depicted in her works; on the other hand, her status as a doctor’s wife and part of a Danish bourgeoise automatically put her in a position where she saw Greenlandic society from the outside, observing it at a distance. A complex duality which we believe is expressed in her works.

Artist and woman

In terms of her education and exhibition practice, Christine Deichmann was part of and reflected the contemporary Danish art scene. However, her images of women and children, including her portrayals of motherhood, are unusual within that scene. As art historian Anne Lie Stokbro has pointed out, motherhood was a rare choice of subject matter among women artists in the late nineteenth century; a period which saw a boom in the number of women artists and in their opportunities to study fine art. Women became independent and no longer felt obliged to fulfil the role that patriarchal society expected of them.50 Seen from a slightly different angle, they were artists who, due to their gender, needed to fight a hard battle to be recognised for being something other than the bourgeois ideal of an ‘angel in the house’ and mother, a role diametrically opposed to the male artist role, which even today continues to be associated with genius and virility as well as a bohemian and eccentric way of life.51 Another Danish artist in Greenland, Ellen Locher Thalbitzer, also created images of motherhood and relationships between women and children. Locher Thalbitzer wintered in Greenland from 1905–06, and in 1914 she spent the summer in Greenland as accompanying wife and assistant to the philologist William Thalbitzer (1873–1958). The question is whether the position as accompanying wives and travelling artists, leaving behind the art scene centred around Copenhagen, gave these two artists greater freedom in terms of their choice of subject matter? Based on their biographical data, neither of them seemed to aim to fulfil the role of ‘angel in the house’. Both trained as artists, exhibited regularly, were actively involved in the art scene, and spent long periods of time in Greenland. Both came from the affluent upper middle class, and all available data indicates that their families supported their decision to become professional artists.52 In a review of the Women Artists’ Retrospective Exhibition from 1920, Ellen Locher Thalbitzer sums up the situation with dry precision:

They were able to paint before us, they have been able to paint throughout time. We have always known that Bertha Wegmann could do it, and her large portrait of an old lady tells us so again. Lei Schielderup’s Portrait of Mrs. Hennings tells us too, though not as clearly as her small, marvellous study of a rose in a glass. Had it been signed by Manet, it would be worth a fortune; as things are, its value is nil or priceless, according to the eyes that see.53

It might seem obvious to conclude that these female artists paint women and children because it is a subject to which they, being women, have unimpeded access. But as art historian Sofie Olesdatter Bastiansen insistently asserts in a piece about the artist Anna Syberg (1870–1914), the domestic should not be regarded as the artistic project itself. If Syberg’s work ‘with watercolour was about capturing and depicting the presence of the moment,’54 then the interruptions found in the (family) home constituted ‘a fundamental condition imbued with a rewarding and positive driving force, one in which the circumstances of life have become an amplifying aspect of a deliberately sought-out mode of artistic expression.’55 This is to say that Christine Deichmann’s spaces of engrossed introspection populated by women and children should not necessarily be read within the context of her position as a doctor’s wife with all that this entails in terms of Danish expat bourgeois living and home schooling. Rather, her choice of subject matter should be seen as a sign that the artistic project she endeavoured to carry out was different from the one pursued by expedition art and the Greenland Painters.

A space of absorption

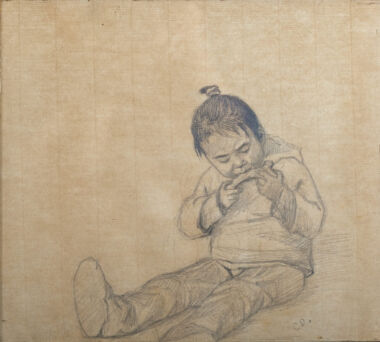

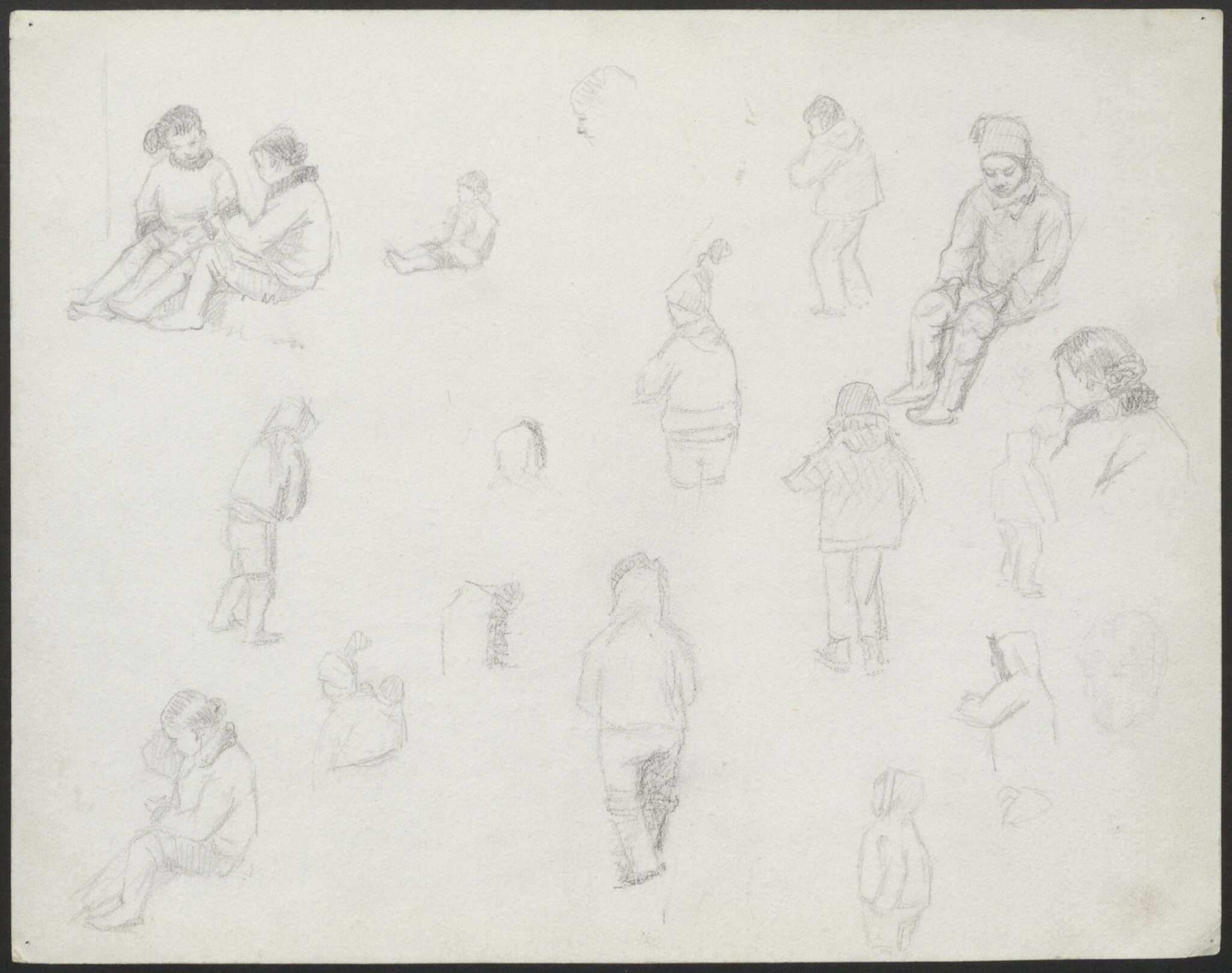

Time and time again, Deichmann draws and paints women and children who are fully absorbed by their task, entirely in the moment. Most of the time we do not quite get to see exactly what they are doing. Looking for parallels, turning to Danish artist Anna Ancher (1858–1935) and her work with space seems an obvious choice. Besides the fact that Deichmann is very likely to have seen Anna Ancher’s works exhibited at Charlottenborg, Deichmann’s professor at the art academy was Viggo Johansen (1851–1935), who was a Skagen Painter like Anna Ancher and furthermore married to her cousin. According to art historian Mette Houlberg Rung, Anna Ancher ‘constructs a space in which a full-length figure (depicted from behind, from the front or in profile) is engrossed by their own chores.’56 Deichmann’s works, like Ancher’s, have a keen sense for such moments of rapt absorption, and they are carefully composed, often based on preparatory sketches. On an undated sketch sheet, Deichmann has drawn various bodies or figures walking and sitting. Their poses seem relaxed, as if the sitters had been observed unaware while lost in their own thoughts. These are studies of human bodies, but also of this distinctive space around the body.

In one work, a mother (or grandmother) sits with two children eating nikku/seal meat. One of the children is on the woman’s lap, while the other leans against her. A line runs through the bodies, extending from the little girl’s fingers holding the nikku, up through the woman’s hand, which holds the nikku for the child on her lap, onwards by way of the same child’s eye contact with us viewers and from here up to the woman’s lowered gaze and further up to the top of her hair. The line ties the subject, mother and children, together in an upward triangle. The triangular composition, the mother and child motif and the recurring use of blue bring to mind Christian motifs of the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, and the image has a certain affinity with an icon, as if it were itself an icon celebrating motherhood.57 The small child on the lap is dressed in a coat of a European cut, but it does not stand out particularly in the image; rather, it blends in with the other clothes in blues, greys and darker shades. Here, the artist’s gaze seems to shift away from being an ethnographic record (of Greenlanders/Inuit in the year 1900) to perhaps being primarily an artwork focusing on issues of form, space and body.

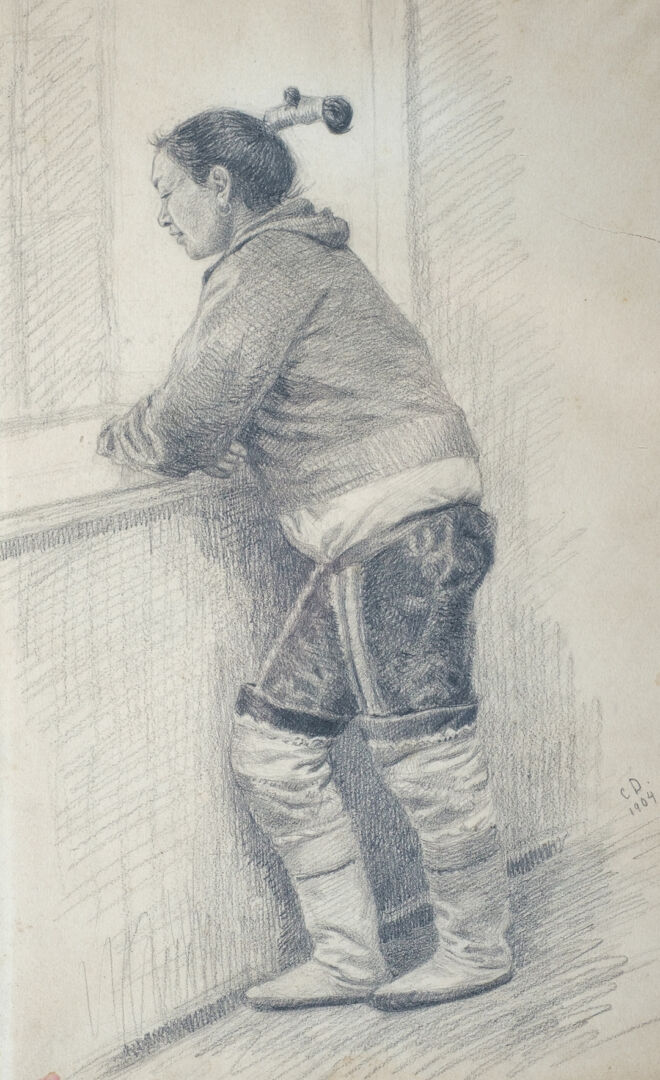

In a drawing from 1904, Deichmann depicts a woman looking out of a window. In a somewhat atypical move for Deichmann, the woman is placed in a clearly delineated room. Leaning on a windowsill, the woman seems completely absorbed by what she can see out of the window: a view to which we as viewers do not have access. Deichmann appears to have focused on depicting the woman in the room; on capturing her facial expression, hair, hairstyle and clothing. The latter consists of a traditional anorak, sealskin trousers and kamiks, but her white cotton underwear can be seen peeping out between the anorak and trousers, which was the height of fashion at the time.58 She seems not to notice Deichmann or us as observers. She possesses a distinctive quality of engrossed absorption which is a recurring trait in Deichmann’s depictions of women and children. Deichmann captures a special mood in this space, but does this atmosphere also manifest a sense of standing on the outside? A yearning to feel like an insider instead, a part of something? Conversely, perhaps this is about maintaining a distance, the Dane versus the Greenlander, a gaze that sees the other as something foreign, something other than oneself? As asserted by the feminist writer and scholar Sara Ahmed, the stranger is not something outside, something one views from a distance. Rather, the stranger is defined precisely through the act of recognition and getting very close, entering a home or intimate space:

The stranger does not have to be recognised as ‘beyond’ or outside the ‘we’ in order to be fixed within the contours of a given form; indeed, it is the very gesture of getting closer to ‘strangers’ that allows the figure to take its shape.59

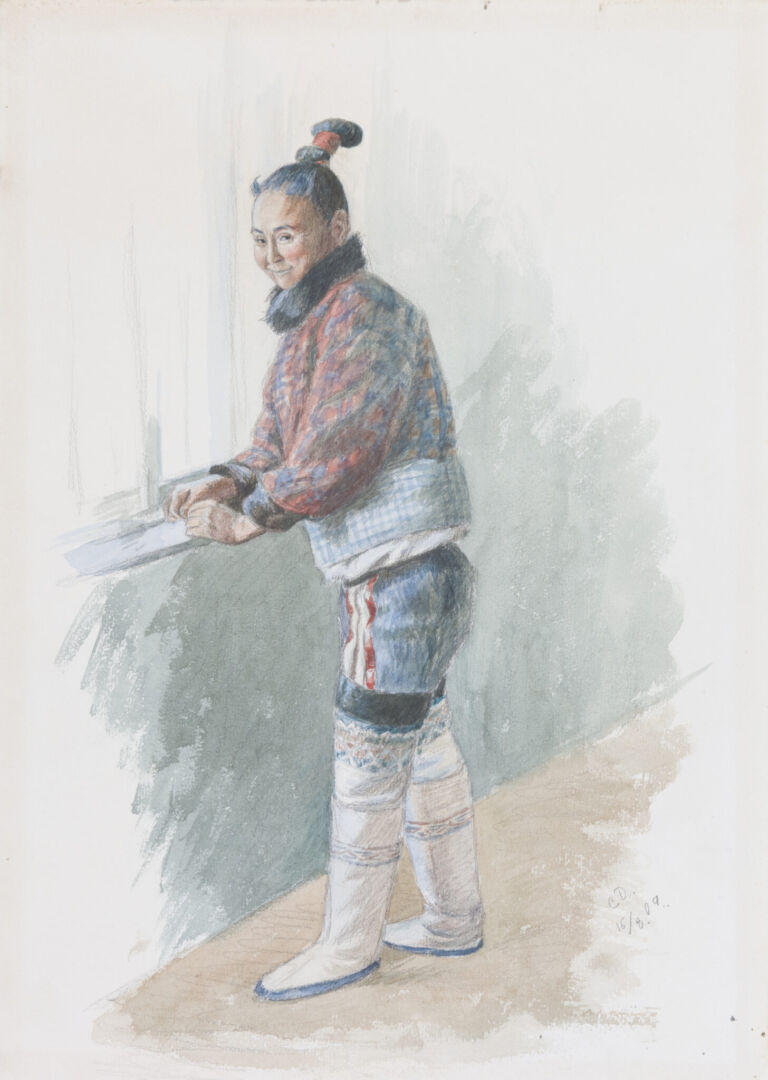

In 1909, Deichmann painted a similar motif in watercolours. Here the woman is clearly posing for Deichmann, standing in a slightly stiff, seemingly not quite natural pose, with her hands resting on the only half-drawn windowsill. The space around her seems unfinished, almost as if it were in a state of disintegration – or of coming into being. Her teasing facial expression is a marked contrast to her slightly stiff and awkward pose, and her gaze reveals an awareness of being observed: she meets our gaze as we meet hers. As viewers, we must ask ourselves: do we have the right to be looking at her, scrutinising her on display in an empty room, being paraded for our gaze? What did Deichmann think of this gaze? What did the model think of Deichmann’s gaze upon her? Was Deichmann aware of her dual role as observer and as the one being watched?

In a diary entry from 1914 published in a later article,60 Ellen Locher Thalbitzer addresses this dual gaze; the act of looking at the other while the other is also looking back at one. The drawing sketched by Locher Thalbitzer would become the basis for the later sculpture called Gertelé, plaster versions of which can be found at the Danish Arctic Institute and at Skagens Kunstmuseer:

Little Gertelé, I wonder if any white woman back home in Europe is so completely at home in her country as you are here in yours – on the rock facing the blue fjord where I have positioned you in order to draw the lines of your maiden neck. […] What do you see out in the fjord, Gertelé? – Not the same as me. Perhaps you see, miles away, a seal’s head emerging like a small dark dot on the shiny surface, hidden from the weak human eyes of the white visitors […]. But do you see the vastness of the mountain range that surrounds the fjord, how deep blue-black are the walls of the Amikittorq mountains in the shadows now that the sun is setting behind them? Do you see how bold, how wild with abandon and generosity was the imagination that laid out the lines of your mountains? […] You squint your brown, slanted Eskimo eyes and look at me sideways. […] You look at me with your big girlish eyes … You gaze upon me as I gaze upon you.61

While the opening words are redolent of the kind of civilisation critique mentioned in the above, singing the praises of the Greenlander while levelling criticism of Europe – Gertelé belongs in her country in a way that no white person belongs in theirs – there is also a dual gaze at play here, a kind of mirroring. This gaze begins with a sense of wonder towards Gertelé: Who are you? What do you see? Locher Thalbitzer asks if they see the same thing or something completely different, and finally turns Gertelé’s gaze towards the artist herself as observer: You gaze upon me as I gaze upon you. Gertelé is not given a voice – we do not know what she is thinking, the words are all Ellen Locher Thalbitzer’s own. The point, however, is that Locher Thalbitzer turns her gaze on herself. Just as Deichmann does with the 1909 drawing of the woman at the windowsill. We do not know what the woman is thinking or what her teasing gaze signifies. But with these double gazes, Locher Thalbitzer and Deichmann both reaffirm their own outlook and the position from which they see.

Gazes embodied and disembodied

The feminist theorist Donna Haraway specifically writes about embodied vision, of how the gaze is connected to the body. Objective (notions of) knowledge, which collates the world in or from a single point of view, and social constructivist (notions of) knowledge, where everything is constructs and negotiations, both apply a gaze that promises an equal and full view of everywhere and from nowhere. Both positions also deny having a share in localisation, embodiment and partial perspective.62 The gaze or the eyes, Haraway writes, have also been used ‘to signify a perverse capacity – honed to perfection in the history of science tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy – to distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power.’63 With the concept of situatedness, Haraway seeks to find an embodied position where the gaze is situated in a body, a place, in a tradition and in a time:

I would like to insist on the embodied nature of all vision, and so reclaim the sensory system that has been used to signify a leap out of the marked body and into a conquering gaze from nowhere. This is the gaze that mythically inscribes all the marked bodies, that makes the unmarked category claim the power to see and not be seen, to represent while escaping representation.64

The landscape paintings and depictions of folk life created by the Greenland Painters and expedition artists see without being seen themselves. Despite the critique of colonialism prevalent in their own day and even among themselves, they depicted Greenland and Greenlanders/Inuit from a position of a total overview, one that might be described as looking from everywhere and nowhere all at once. This point of view is particularly accentuated when the works have been featured in ethnographic exhibitions. In Deichmann’s works depicting the woman at the window and the mother with two children, we as viewers are being looked at in turn, confronted with our own gazes and our own embodied position and situatedness. The woman in the window casts a mischievous glance back at us, and the boy’s gaze makes us aware that we have entered an intimate (and inaccessible) space that is not ours. Locher Thalbitzer also ties her gaze on the girl Gertelé to a specific body, a specific place; she announces the position from which she sees. This double or mutual gaze has a parallel in Marchwinski’s reading of L.A. Schou’s Portrait of a rag picker. The Roman midget Francesco Colombo (another work created by an artist abroad): the subject’s eyes look back at the viewer/artist, becoming a mirror – and the fragility and vulnerability shown by the ragman becomes the artist’s own.65 Christine Deichmann makes her own presence and position as outsider visible, and Locher Thalbitzer proclaims herself to be someone who does not know what the girl Gertelé sees. When Locher Thalbitzer says You look upon me as I gaze upon you, she hints at the possibility that the human being presented in the scene is not simply an object that is laid bare to (and fully seen/taken in by) her lines, but a subject to whom she and we cannot gain access, one that mirrors and meets our gaze. With this gaze, Deichmann’s images challenge the gaze of the male Danish artists in Greenland who see without being seen, and the gaze which, in landscape paintings and depictions of folk life, conquers both land and people, Kalaallit Nunaat and Inuit (Greenland and its indigenous people). At the same time, the intimacy of Deichmann’s motifs is also the place where a sense of alienation lurks: Deichmann remains an outsider, the one who does not belong.

Christine Deichmann’s works are representations, definitions, statements and views of Greenland; the woman, mischievously looking at us while posing by a window, does not escape being ‘the stranger’ or becoming the image of the Greenlandic as something other than the Danish. On the one hand, Christine Deichmann’s works challenge the non-embodied unmarked conquering gaze, but at the same time Deichmann’s position as being outside the intimate space shown in the scenes is maintained; just as Locher Thalbitzer inscribes a distance and an alienation between her and Gertelé.

All of the artists who travelled to and in Greenland became, more or less intentionally, ethnographers of a kind. Their choice of subject was embedded and upheld in a European narrative and view of Greenland that can be traced right up to the present day. In this article, we have argued for a nuanced reinscribing of these artists, taking Christine Deichmann as the focal point while also considering colonial and art historical narratives in Deichmann’s time. This has been done first and foremost to posit colonial history/histories within Danish art history. Christine Deichmann and the other Danish artists in Greenland before 1940 should be viewed against the backdrop of the travels and grand tour activities which were in many ways defining for numerous Danish and European artists up through the nineteenth century. Travels that contributed to establishing certain views (and definitions) of other places and people. The Danish artists in Greenland joined all the other Danish travelling artists in contributing to defining Denmark as a nation, including what was truly Danish and what was not. In various and problematic ways, this continues to have reverberations in our present day – a time when we are ready to begin the urgent and necessary task of decolonisation. On the one hand, Christine Deichmann’s images run counter to the outlook on Greenland prevalent in the art of the period, but on the other hand she cannot escape the time of which she was part. This article has sought to point out this dual gaze and unpack the nuances it encompasses.