Summary

A corpulent elderly Aspasia, an arse-warming, pipe-smoking Queen Christina, and a naked Susanna standing on her hands: Kristian Zahrtmann’s (1843-1917) history paintings of women are unlike most from the minds and hands of his contemporaries. Zahrtmann often depicts women in unconventional and ambiguous ways, contravening the beauty ideals and art-historical traditions of his time. This article offers a queer look at Zahrtmann’s historical images of women, examining their complexity, paradoxes and potential for criticising norms.

Article

During his lifetime, Kristian Zahrtmann (1843-1917) painted many works portraying women from the world of history and literature. He is particularly known for his paintings of Leonora Christina Ulfeldt (1621-1698), the daughter of King Christian IV who spent nearly 22 years of her life in prison. From 1870 to 1914, Zahrtmann produced more than 20 paintings of the king’s daughter, in addition to a number of drawings and sculptures.1 With these images, Zahrtmann played an instrumental role in the creation of the myth of Leonora Christina– and, to some extent, in the creation of the myth of himself.

Zahrtmann painted Leonora Christina more than any other woman. In many of his works she appears to be a symbolic figure or stand-in for the artist himself.2 By including his own sculpture, Leonora Christina leaving prison [fig. 1], in a number of historical interiors, Zahrtmann created a connection between himself and the historical events depicted in the paintings. And by the artist’s own wishes, she even appears on his gravestone at Copenhagen’s Vestre Kirkegård Cemetery [fig. 2].3

Zahrtmann was the only artist who painted Leonora Christina as an older woman – and as a heavy one at that. It caused great furore when he exhibited the first paintings of her. Many criticised the artist for lacking a sense of beauty. They did not find this corpulent, coarse, elderly female figure to be a suitable representation of the noble Countess Ulfeldt.4 Yet Leonora Christina was far from the only woman whom Zahrtmann depicted in an unconventional matter – and she was not the only female figure with whom he had a special connection. However, the strong focus on Zahrtmann’s Leonora Christina works has cast a shadow over many of his other historical paintings of women. This article thus seeks to shed new light on this oft overlooked part of the artist’s oeuvre.

A masculine ideal

[I] don’t have much interest in women who paint. Only rarely are they able to sacrifice themselves for a cause. In reality, there are no female artists in the world. Sappho – yes, back then the culture of women was on a much grander level. And singers, actresses and dancers are a completely different thing – they only reproduce the thoughts of others. No, the self-sacrificing, sober art of men is that on which we live and rejoice.5

The words quoted above come from Zahrtmann himself and has been cited many times in the literature on him ─ often in connection with examination of his relationship to and view of women. They clearly indicate that he was not very fond of women. Surely, female students were not welcome in Zahrtmann’s classrooms.6 He even believed in the old custom which held women should not eat in the company of men, as this would “give women respect for the greater culture and morality of men”.7

In the light of misogynous statements as that above, it may seem paradoxical that Zahrtmann choose to fill his pictorial universe with strong women ─ and that he even let them play the main role in many of his historical paintings. But the women we meet in Zahrtmann’s works are not ’ordinary’ women. They often demonstrate a marked masculinity, both physical and behavioural, and in this sense they do not stand in contrast to the artist’s masculine ideal. On the contrary, they appear to confirm it.

Nonetheless, the artist’s relationship with and perception of women is likely more complex than is often represented. According to art historian Morten Steen Hansen, for example, Zahrtmann exchanged more letters with the wives of male painters than with their respective husbands.8 He also commissioned and purchased numerous works by the female artist Elisabeth Neckelmann (1884-1956). In an undated letter to her stepfather, painter Peter Hansen, Neckelmann writes about Zahrtmann’s artistic support:

Yesterday I was at Den Fri [The Free Exhibition] to draw your picture for the Art Society when I met Zahrtmann. We spoke at length about art, your art and my art, there is nobody I feel so free with as with Zahrtmann. He was most fond of your painting from Holte, where Bimse is standing up, a lot of good words about it, and since I was in the process of drawing, he asked me to make a drawing of it that I would receive DKK 100 for. I almost fainted, just think, DKK 100. […] Well! Then today I received a letter from Zahrtmann in which he commissioned a small canvas with 2 tulips that he also will give me DKK 100 for. Just think that I am going to paint a picture for him, who I am so enthralled by. Not that I think he is fond of my art, but that he wants to support it, the man who otherwise does not like female painters – it is exceptional.9

Apparently, Neckelmann was far from an ‘ordinary’ woman for her time. Her hair was cut short for most of her life, and sometimes she dressed in masculine attire including a tie or bow tie. She also lived a life that differed from the majority of women of her time. For example, she showed an interest in ‘manly’ tasks and in her youth helped her stepfather build a boat. For a number of years she lived with the pianist Ingrid Holm (1893-1966), and she never married. In 1924 she became the chair of the Female Artist’s Society, where she made significant contributions to the fight by female artists for equality with their male counterparts.10

Zahrtmann’s interest in unusual women is also reflected in the aforementioned quote, in which he points to Sappho as an exception, superior to other women. Sappho (c. 630/612 – c. 570 BCE) is the most famous female poet of antiquity. She is especially known for writing poems about love of women, and is therefore directly associated with the term for female homosexual love: ‘lesbian’ refers to the Greek island of Lesbos, where Sappho lived for most of her life.11

Zahrtmann’s history paintings demonstrate a similar interest in historical female figures who lived out their gender differently from the majority of their contemporaries. Even in Zahrtmann’s own lifetime, these historical women from the 1500s, 1600s and 1700s stood in opposition to bourgeois norms of gender and sexuality. In his paintings, he often focused on female outsiders such as Sigbrit Villoms (c. 1532) and Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), whose lives contrasted with established gender norms. Zahrtmann himself also lived out his gender in an unconventional way; in this sense, many of his painted women appear to be female alter-egos or representations of himself.12

Queen Christina’s manly extravagances

The painting of the 17th century queen, Christina of Sweden, is an example of Zahrtmann’s history paintings featuring unconventional, masculine women. In Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini from 1908 [fig. 3], the queen’s appearance is largely in line with what was traditionally expected of a woman. She is clad in a dress and jewellery, with long hair and a narrow waist, yet she exudes distinct masculinity through her behaviour.

Queen Christina was an unusual woman in her time. She was brought up in the same way as a male heir to the throne, which included learning to ride horses and hunt, as well as a high level of schooling. She became regent at the age of 18 but abdicated 10 years into her reign, after which she converted to Catholicism and moved from Stockholm to Rome, where she lived for the rest of her life. After her death, she became the first female monarch to be buried in St. Peter’s Basilica.13

According to the common narrative, at birth the queen was originally assumed to be a boy, and throughout her lifetime many held that she had a masculine manner and a very masculine appearance.14 Even after the queen’s death, speculation about her gender continued to swirl ─ including speculation that she had been born a hermaphrodite. In 1965, this speculation led to the reopening of the queen’s tomb so that scientists could study her remains and determine her biological sex. The bones showed nothing but typical female traits most likely, the speculation had no other basis than the fact that she behaved differently from what was expected of a woman.15

A newspaper article in Politiken reports that Zahrtmann was aware of the story that people thought the queen was a boy. He also knew of other stories about her, including that in her youth she commanded a lady-in-waiting to read lewd stories aloud to her and laughed at the servant’s blushing, and that as an adult she attended the opera in men’s clothing to surprise everyone. The writer Svend Leopold also recalls how Zahrtmann was “greatly captivated by Queen Christina of Sweden’s manly extravagances”.16

In the centre of the picture, the queen, dressed in blue, is surrounded by courtiers in her Roman palace, Palazzo Corsini. The painting depicts a situation in which she supposedly lifted up her dress to warm her bottom at the stove. In the background, two of the courtiers are seen smiling at the sight of her partially exposed body, while a crucifix in the window stands in contrast to the salacious behaviour. In front of the queen, a third courtier holds up small golden statue for her to behold, and with a touch of humour, Zahrtmann uses the light on the statue to emphasise what the viewer cannot see. The small figure in drapery has its back to the viewer, and the light falls on it so as to precisely illuminate its bottom.

Zahrtmann’s painted queen differs in a number of ways from a traditional female role ─ first and foremost through her uninhibited buttocks warming and her complete lack of concern about the amused looks of her courtiers. Add to this the pipe in her mouth, the sculpture in front of her, and the opened book in the foreground, all of which attest to her ‘manly’ interests. In the 1600s as well as in Zahrtmann’s own lifetime, intellectual pursuits such as the creation and study of art and literature were generally reserved for men. The same was true of cigar and pipe smoking, which is why smoking women were a popular motif in caricatures of that time.

In the late 1800s, however, these perceptions and expectations of men and women slowly began to change, driven in part by a number of intellectual and well-off women known as the ‘blue stockings’, who fought for equality between the sexes. As part of this struggle for women’s liberation, tobacco was used by a growing number of women as a weapon and symbol of freedom.17 The painting can thus be viewed in the context of women’s emancipation and movement into ‘male territories’ around the turn of the 20th century.

As is typical of Zahrtmann’s history paintings, the work presents a paradoxical approach to gender. The queen is the focal point in a gathering of men, where she does so many demonstratively manly things that it almost becomes a parody: all at once she reveals her body, reads a book, contemplate art, and smokes a pipe. The laughter that this painting may evoke appears to serve a multitude of purposes. In part, it creates a distance from the provocative scene and makes it easier for a bourgeois art-viewing public to engage with the work. At the same time, it opens the door to numerous and potentially contradictory interpretations, depending on the eye of the beholder. For example, it can be interpreted as a ridicule of the emancipated women of the time and their tendency to act and behave as men, but it can also be interpreted as a ridicule of the idea that certain interests and actions are naturally associated with a specific gender.

Female masculinity: Masculinity without men

Masculinity has traditionally been synonymous with men and manliness.18 According to the American professor Jack Halberstam, masculinity is not something that grows out of the male body and is intrinsic to the male sex. Rather, it is a social construction that reaches far beyond the biological male body. This means that masculinity also exists independently of men.19 According to Halberstam, it is impossible to fully understand masculinity without involving women in the equation. Women have played a very important role in the emergence of today’s masculinities, and according to Halberstam, masculinity is at its most complex and transcendent when it is not tied to a man’s body.20

In the light of the above, Zahrtmann’s history paintings do not simply portray women who look or act like men. They offer alternative masculinities, standing in opposition to the ‘normal’ masculinity associated with men – particularly heterosexual, white, middle-class men. From a present perspective, it seems fruitful to focus on the latent and indeterminable in female masculinity as it appears in the art of Zahrtmann.

Around the year 1900, at which time Zahrtmann was active as a painter, doctors were convinced about an unambiguous connection between a masculine appearance and sexual orientation in women. In their pursuit of de-masking lesbianism, making it easy to distinguish between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ women, masculinity became a visible identity marker.

The definition of homosexuality was based on the gender role patterns of the time, whose perversion was seen as reflected in the homosexual. A pervasive view was that these people possessed the behaviour and being of the opposite sex – a kind of spiritual hermaphroditism – and thus homosexuality was defined as “sexual inversion”. Unlike previous epochs which saw same-sex desire as sodomy, sexual inversion was not just about the sexual act. The entirety of the sexual invert’s personality and body was instead permeated by their sexuality – even if the person was not sexually active.21 One proponent of this view was the Danish doctor Christian Geil, who in 1893 described the gender crisis of the sexual invert as follows:

But most often, he [the sexually invert man] has other psychological conformities with the woman; he is anxious, deliberate, vain, has a pronounced emotional life, a great sense of aesthetic pleasure, taste and proclivities for female handicrafts. In a similar fashion, the sexually invert woman has an interest in emancipated being and attire, enjoys smoking and drinking, and exhibits an absolute aversion to female work.22

Feeling or acting like the opposite sex was thus an important characteristic of the homosexual woman. The idea of a male soul in a female body helped to make the phenomenon comprehensible for the general population. Understood in this way, many of Zahrtmann’s history paintings could by his contemporaries be seen to imply a queer female masculinity.23 Halberstam notes the existence of female masculinities across time, none of which can be fixed as unambiguously hetero- or homosexual, cis- or transgender. The paintings of Zahrtmann likewise challenge any set identity: the gruff and manly Aspasia, whom we will meet shortly, is historically heterosexual and the same goes for the masculine and steadfast, but loyal wife, Princess Leonora Christina. The art of Zahrtmann opens up to a complex understanding of female masculinity – masculinity without men.

A preference for older, unsightly women

A glance at Zahrtmann’s history paintings of women reveals a consistent preference for old, unsightly and sometimes corpulent women. This presentation of women is largely the antithesis of the artist’s history paintings of men, particularly in his later works, which typically present young, attractive and fit men.24

In paintings where women play the main role in a historical situation, Zahrtmann repeatedly chose atypical or untraditional models who stood in contrast to the beauty ideals of the time. What others might have found unfortunate in a model, he chose instead to emphasize in his works. For example, his two favourite models were the corpulent Madame Ullebølle [fig. 4], whose rough physiognomy resembled that of a traditional man, and Thora Lund [fig. 5], later Mrs. Mynzberg, who due to an eye disorder had a distinctive squint-eyed look.

Zahrtmann apparently never hid the fact that he thought himself to be ugly.25 In other words, he identified with the ugly or the unsightly, understood as an external phenomenon. There is reason to believe that his interest in these older, corpulent and, in a traditional sense, unsightly female figures was due to their similarities with himself – similarities not only bound by physical or age-related traits, but also having to do with their latent, but not at all given identities as ‘sexually invert’ or queer.

SAt the same time, ugliness and age specifically allowed Zahrtmann to portray women who were more than just sexual objects for the man’s gaze. His paintings of historical women were created during a time when many women had begun challenging the predefined gender roles and demanding greater freedom and socio-political rights. For some men, the challenging of the traditional role of women aroused a fear that materialised as warnings about the dangerous power of women, and in images of ‘femme fatales’ in art, theatre and popular culture.26 Femmes fatales or ‘fatal women’ were self-assured and erotically self-aware women who seduced, dominated and ultimately destroyed men. Unlike these rather common portrayals of women during his time, Zahrtmann’s women did not derive their strength from an alluring appearance and associated sexual appeal. On the contrary, their strength was rooted in a muscular, intellectual and/or moral superiority that linked them with the idea of the male gender.

From young women to old wives

Zahrtmann’s history paintings were quite subjective, and he often rewrote the historical narratives and portrayed alternative versions in his paintings. For example, in a number of works he depicted historical female figures traditionally presented as young and beautiful as old and unsightly women.

As early as 1880 he painted Aspasia with the Bust of Her Son Pericles [fig. 6], in which Aspasia took shape as an elderly, overweight woman. The painting aroused great discussion because for many Aspasia did not match the literary description of her as one of the most beautiful women in ancient Greece. In 1893, art historian Francis Beckett wrote the following about this work:

[…] a voluptuous matron in whom one futilely searches for anything reminiscent of the lovely Ionian woman whose spirit and grace had brought the flower of Athens’ men to her feet. She wears a coarse, dirty grey drapery that only slightly resembles the soft Greek chiton, wears it like a washerwoman and not like a woman who has become privy to all the secrets of the bordel. In a slightly apathetic manner, she rests her heavy hand on the scalp of a plaster bust, a cast of a Grecian original, depicting an athlete, intended here to represent a portrait of her executed son.27

Critics like Beckett were particularly outraged by the fact that Zahrtmann made the proud Aspasia so fat. But Zahrtmann had a counter to this critique. He had found a note showing that when Greek sculptor Phidias modelled Aspasia, he had to use larger and broader measurements than usual. Thus he argued that Aspasia, like many women in their old age, had become rather corpulent.28

There is a pronounced contrast between the old, full-bodied Aspasia in wrinkled garb and the young, sharply cut male figure. This contrast reflects the difference between male and female figures in Zahrtmann’s history paintings: old, full-bodied women on the one hand, and young, muscular men on the other. The work also visualises the cultivation of an antique Greek ideal of masculinity, a defining trait of Zahrtmann’s history painting.29

Although Aspasia fills most of the canvas, the viewer’s eyes are drawn to the bust of the young man. While Aspasia almost blends into the textile-clad surroundings, the white bust stands out clearly in the room. The light almost seems to be emanating from it. The exaltation of the masculine is further underpinned by the fact that the young son’s bust is literally placed on a pedestal. Yet, however, Aspasia relates to the bust with an air of superiority. One hand rests nonchalantly at her side, while the other rests heavily on top of the depicted bust, as if she is weighing it down.

Zahrtmann had the idea of a motif of a sorrowful woman by a picture of a young man, and therefore searched for historical examples of women who had lost a young son, leading him to the story of Aspasia.30 But Aspasia was far from an ordinary mother figure. As with many of other women in Zahrtmann’s paintings, she was unusual for her time. She was a highly gifted and well-educated hetaira from Miletus who was known for her beauty and intelligence. She was the lover of the Athenian statesman Pericles and at the centre of the group of intellectuals with whom Pericles surrounded himself. It is said that she also had a great influence on his political beliefs and practices.31

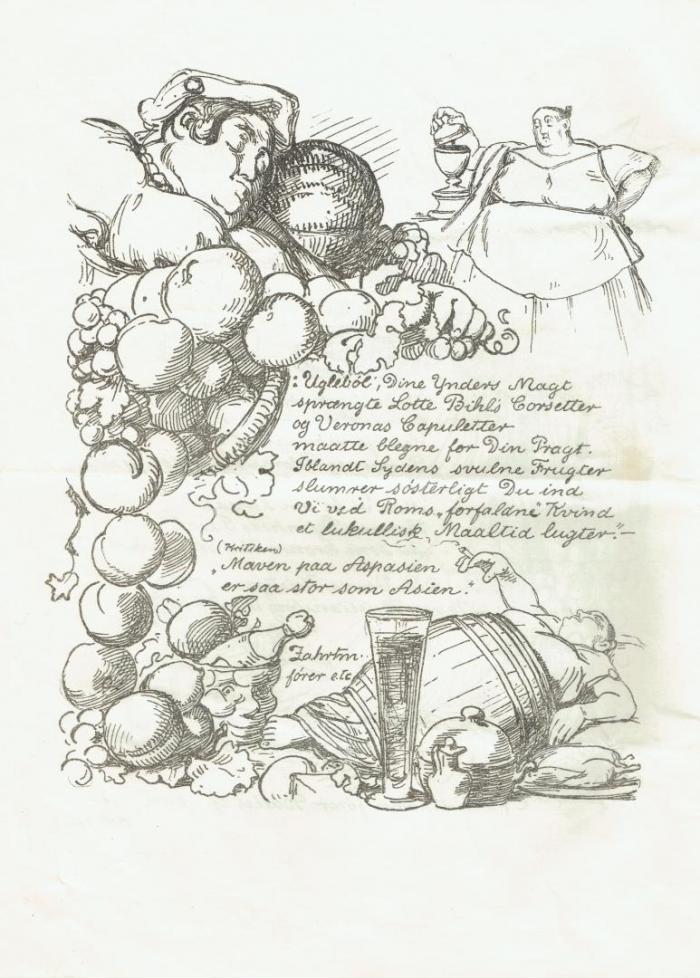

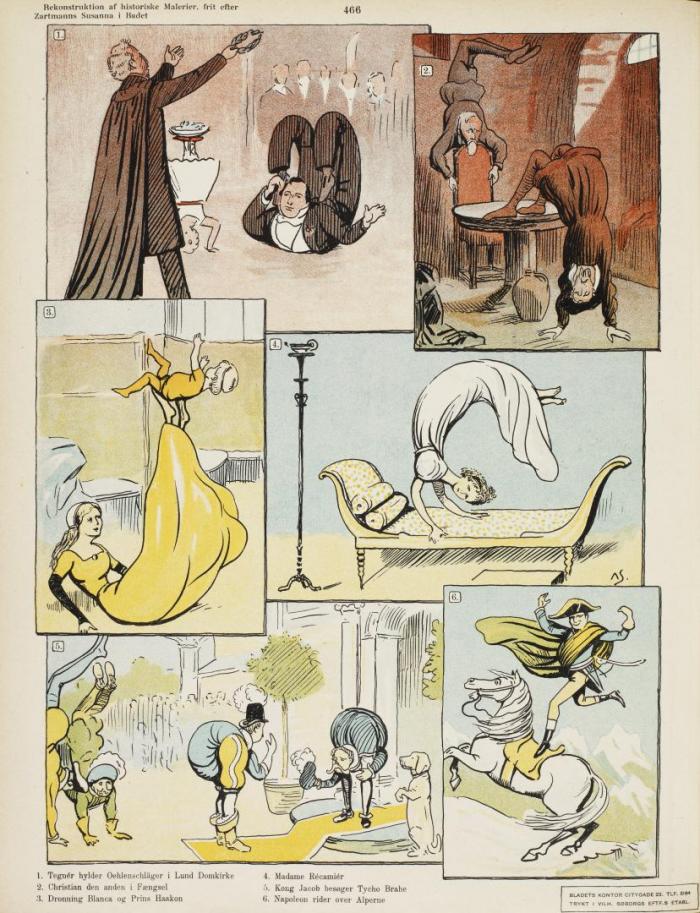

The model for Aspasia was the aforementioned Madame Ullebølle. Zahrtmann first met her in 1874, and he painted her many times over the next 15 years.32 She became his most famous model, and over time she also began to appear in the works of other Danish artists, including J.F. Willumsen (1863-1958).33 For Zahrtmann’s friends and social circle, Ullebølle became the epitome of the artist’s ideal of beauty. On the front page of August Jerndoff’s “Mephistopheles Song” [fig. 7], composed on the occasion of Zahrtmann’s 60th birthday in 1903, Ullebølle symbolically played the role of Venus, the Roman god of love and beauty, with references to Botticelli’s iconic Renaissance painting. A full page of the song was also dedicated to her, depicting numerous Ullebølle caricatures between an abundance of lush fruits, while the associated verse is particularly focused on her overweight body. The second verse of the song appears at the top: “Uglebøl, the power of your graces burst Lotte Bihl’s corsets.” The verse concludes with a reference to the aforementioned Aspasia work: “(The critic) The belly of the Aspasia is as big as Asia.”

Turning gender upside down

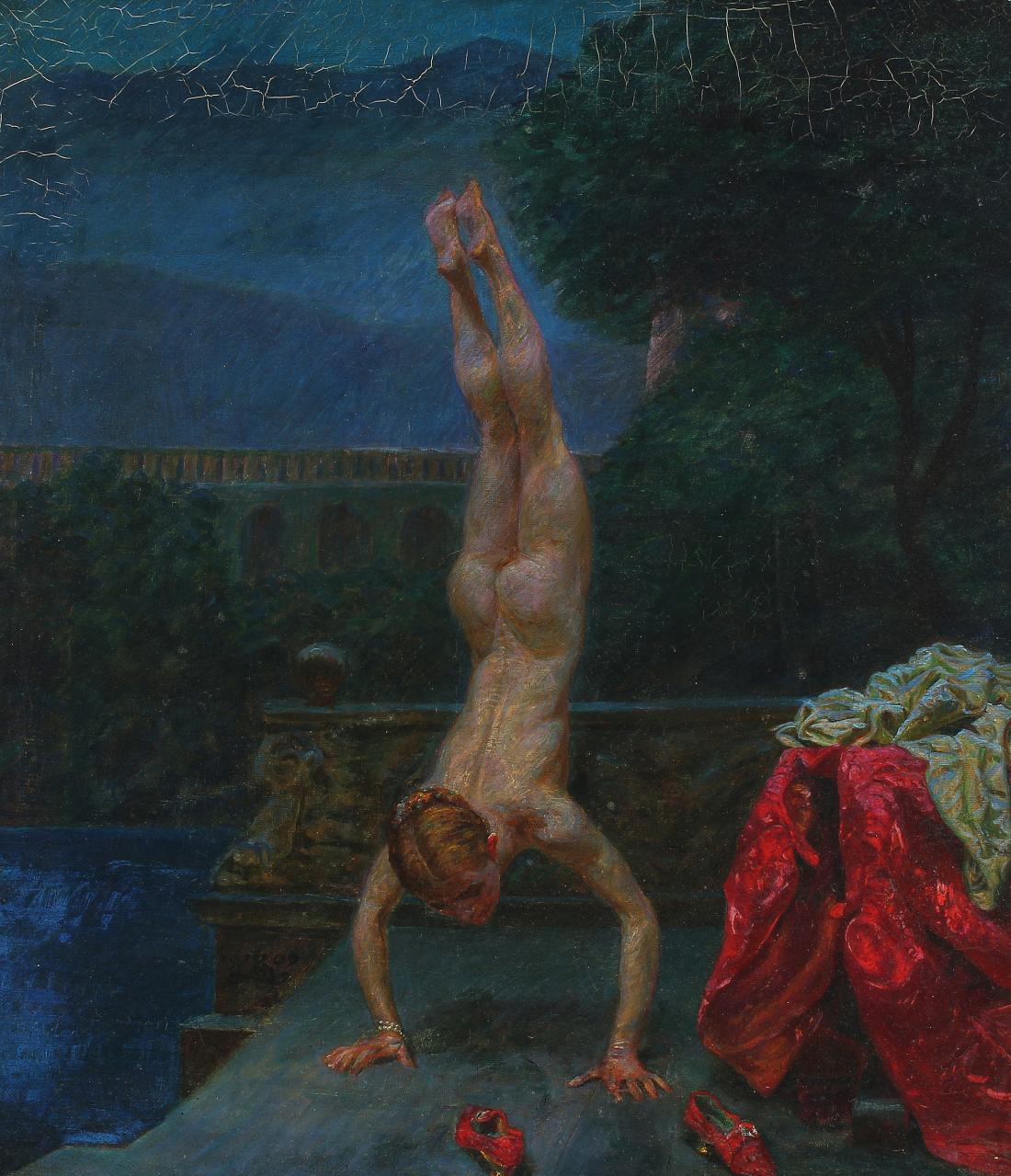

SAs described, Zahrtmann turned the conventional upside down in his history paintings, for example by painting women who broke with social norms and gender roles, and who deviated from the usual iconography. With the painting Susanne at her Bath, 1907 [fig. 8], Zahrtmann literally turned gender and tradition upside down.

Susanna in the bath is a favourite motif in painting from the Renaissance through to the 20th century. She is typically portrayed as a young and modest woman who is secretly watched and coveted by two old men while in the bath. In Zahrtmann’s version, however, Susanna (or Susanne, as he calls her) is alone without the peeping men. Furthermore, she is not in the bath, but standing on her hands in front of the water. She is bare naked, and like the Swedish Queen Christina, she exhibits her naked body without inhibition – a far cry from the biblical story of the shy woman who sighed “I am straitened on every side”.34

Although Zahrtmann’s painting differs from tradition, it maintains a clear connection to it, since it contains direct references to Rembrandt’s Susanna painting from 1647 [fig. 9]. Rembrandt was one of Zahrtmann’s great artistic idols, and he shared Zahrtmann’s affinity for corpulent female figures.35 In his work, Zahrtmann adopted the composition of Rembrandt’s painting, with Susanna in the middle of the work, water to the left, a bench to the right, and a tree dividing the two parts of the image from each other. What is particularly striking, however, is the repetition of the red shoes and the red cloth, which in both works are located at the bottom right corner.

In Rembrandt’s work, the red-haired, round-shaped Susanna stands at the water’s edge and looks out towards the viewer as she is groped by one of the two elderly men. Her face expresses the surprise of one who suddenly and quite unexpectedly is exhibited for the public to see. As the British art critic Edwin Mullins points out, the light emphasizes this sense of surprise. In Rembrandt’s work, strong lighting illuminates all of Susanna’s body, like the light of a powerful projector pointed towards the scene of a crime.36 And, by virtue of the direction of Susanna’s gaze, the offending parties are not only the two men in the picture, but also the viewer outside of the canvas, who becomes an accomplice voyeur.

In Zahrtmann’s version, Susanna also has red hair, but otherwise there is not much similarity between the two female figures. Zahrtmann’s Susanna is fit and muscular, and in that sense has a traditional manly appearance. She is also tanned, unlike Rembrandt’s female figure, which indirectly tells the story of a body that has been exposed to the sun’s rays for a long time – and thus, potentially, to the gaze of others. In Zahrtmann’s version, Susanna has also dropped the white cloth that Rembrandt’s Susanna uses to conceal her body. At the same time, the work-viewer relationship is completely different, as Susanna does not occupy the original role of victim. Instead, she is transformed into an active subject and appears to be so unconcerned with and independent of her surroundings that she turns her back to the viewer.

In two interviews with Per Pryd (Andreas Vinding) in Politiken in 1907, Zahrtmann declared that the image of “the young girl, who quite freely enjoys herself after the bath” was created as a protest of the academic prize assignments.37 In 1906, he humorously wrote to his friend Hans Christian Christensen that he had a strong desire to paint a Susanne doing a handstand in the bath because the academies had abused her legs.38

The painting also seems to be a witty and ironic treatment of a well-known art historical motif – especially when one considers that Zahrtmann used a male model for the work. The model was the circus artist Barley Petersen, a “clown” or “snake man” as Zahrtmann called him in a letter to his mother.39 By presenting the figure with its back to the viewer, Zahrtmann kept the breast and genitals hidden, and thus also the biological sex of the model. This allows for two readings of the painting: one heterosexual and one homosexual. However, it was Zahrtmann himself who revealed that the model for the work was a man. Therefore, it must have been a point of importance for the artist. By having a man take the role of Susanna, the painting is not just a representation of a masculine woman, but of a man who, by virtue of the work’s title, presents himself as being or identifying as a woman.

In art history, the woman has traditionally served as the passive object of desire for the (assumed) heterosexual, male viewer. Conversely, the man has traditionally been portrayed as active and strong for the same viewer to identify with. This means that the represented women often conceal their nudity from the viewer, while male figures shamelessly exhibit themselves in all their nudity [fig. 10-11].40 Zahrtmann’s painting of the nude, uninhibited Susanna thus resembles the way in which artists have traditionally portrayed the man. In other words, the woman’s traditional role as object is converted to that of subject. By using a male model and depicting Susanna standing on her hands, Zahrtmann literally and figuratively turns tradition on its head.

Men who pretend to be women

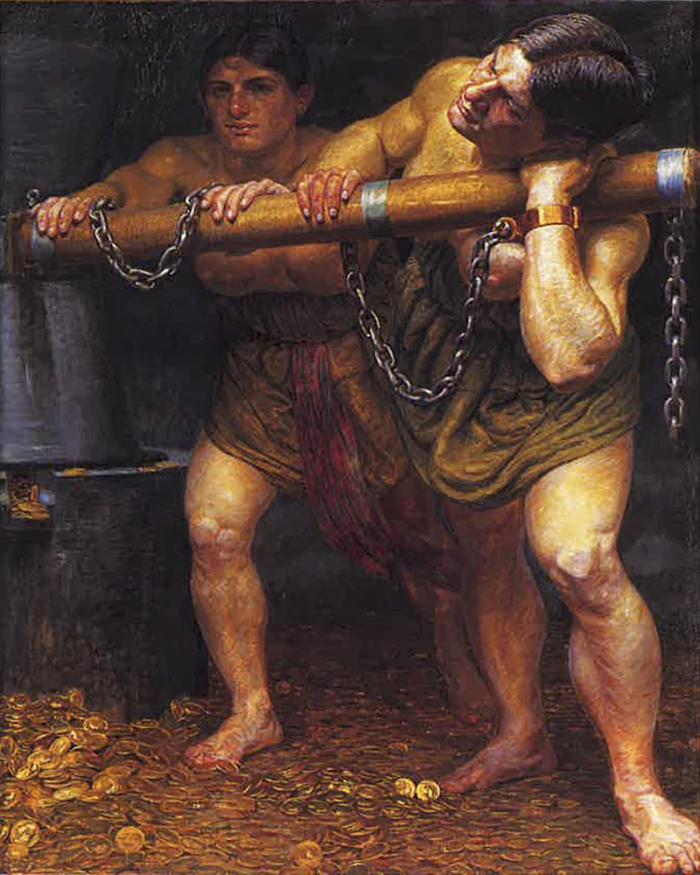

For the painting Fenja and Menja in Chains Grinding Gold for Frode Fredegod from 1906 [fig.12], aZahrtmann once again used a male model. According to artist and art critic Adam Sopus Danneskiold-Samsøe (1874-1961), a certain carpenter was used as the model for both female figures.41 In a study painted prior to the work (now in the collection of Malmö Art Museum) we can catch a glimpse of a pair of added breasts on top of the muscular model’s torso [fig. 13]. In the final version of the painting, the mix of traditional male and female bodily characteristics are even more pronounced.

In Nordic mythology, Fenja and Menja are two giant women whom the Danish King Frode forced to grind out wealth and happiness using the magic mill Grotte. When the king goes too far and takes advantage of the women’s labour, they decide instead to grind out death and destruction over him. In Zahrtmann’s painting, the two giant women are depicted with chained, half-naked bodies while working at the mill.

TThematically, Zahrtmann’s painting is about a powerful man’s exploitation of two women’s bodies, which results in money. In this sense, the work can be understood as a reference to the growing rise of prostitution in Zahrtmann’s time. The painting is also filled with sexual undertones: the women’s nudity, the chains on their bodies, and the large, exposed breasts sticking out from under the wooden handle. Yet the women’s muscular strength also reveals their potential to fight back, and the viewer familiar with the story knows that these women will soon resist the king and exact their revenge. In this sense, the work can be read in the context of the women’s liberation movement of the time, and the first steps towards breaking the chains of patriarchy.

The figures are ambiguous and literally on the edge of gender, as they appear with a mix of traditional female and male body signs. This concoction of gender expressions is made possible by the mythological universe from which the motif derives. The breasts point to a physical femininity, while the short hair and large, muscular limbs point to a physical masculinity. This duality is reflected in the doubling of what is clearly the same figure.

As with many of Zahrtmann’s history paintings, this work points back in art history. More specifically, it seems to refer to Carl Bloch’s famous painting, Samson and the Philistines from 1863 [fig. 14]. Both works portray chained, muscular, half-naked bodies working at a mill, and in both works the main figures have short, dark hair. The two stories illustrated also have thematic correlations, but whereas Bloch’s work is the story of a man’s enslavement by a woman, the genders of these two roles are reversed in Zahrtmann’s painting.42 Zahrtmann also reversed the composition so that the giant girls are moving in the opposite direction of Bloch’s Samson.

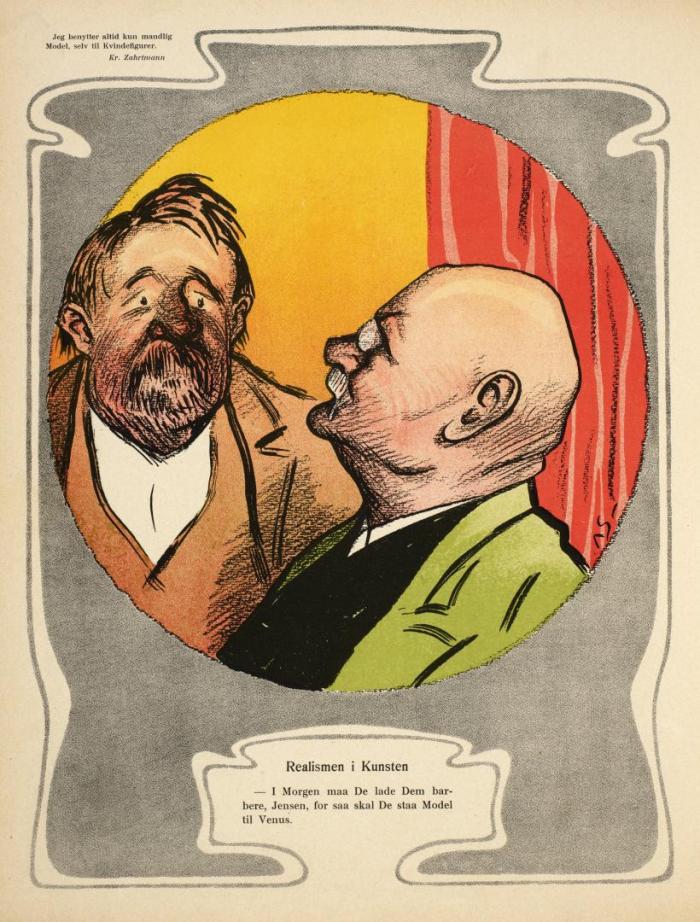

As demonstrated above, Zahrtmann used male models for many of his female motifs. However, he never used female models for his depictions of men. Zahrtmann’s use of male models is part of an old tradition. From the Renaissance onwards, it was common practice for female figures to be based on male models, as it was considered inappropriate for women to be undressed in front of the male painters. It was not until the early 1800s that the use of nude female models began to take hold at the art academies. In Zahrtmann’s lifetime, nude female models had long since become common practice. Therefore, his particular use of male models was the subject of numerous caricatures. For example, in the satirical weekly magazine Klods-Hans [fig. 15-16], the artist was drawn next to a large, bearded gentleman with the caption: “Tomorrow you will have to shave, Jensen, because you are going to be the model for Venus.”43

Zahrtmann himself was very open about his use of male models. It was apparently very important to him that the viewer knew a male model had been used for a female figure. The intention was not to mislead the viewer into believing that these were ‘real’ women. They were supposed to know that the model was a man.

Women who pretend to be men

In Struensee and Caroline Mathilde at the dead body of Queen Sofie Magdalene from 1910 [fig. 17], feminine and masculine expressions of gender intertwine once again, as the pregnant Caroline Mathilde is dressed in a man’s riding suit. At the centre of the painting is the deceased Queen Mother Sophie Magdalene’s body, with the two lovers, Caroline Mathilde and Struensee standing by her side.

In the art historian Morten Steen Hansen’s analysis of the painting, the smaller size and pregnant belly of the queen makes her unmistakably feminine, thus adding a touch of the comedic to her masculinity. In other words, she clearly appears as a woman who is trying to play a man.44 Yet her costume also creates an opportunity for a male, homosexual voyeurism for Struensee in the painting, as well as for the viewer outside of the canvas. The queen’s pregnant belly could just as well appear to be a man’s potbelly.

The large painting in the background of the image appears to further reflect that the man becomes the object of the gaze. The painting is most likely Johann Salomon Wahl’s Portrait of King Christian VI (c. 1740: whereabouts unknown), which portrays the dead Queen Sophie Magdalene’s husband. And as a piquant detail, the king in the portrait, Caroline Mathilde and Struensee are all holding staffs or riding crops in their hands. This positions all of them within a common circle and also suggests the presence of a sadomasochistic desire that connects pain with pleasure.45 The presence of the dead Queen Mother Sophie Magdalene’s body adds seriousness to the scene, which perhaps portends the potential dangers associated with living out one’s sexual desires.

A broad spectrum of femininities

Zahrtmann’s works contain a broad spectrum of femininities, from masculine women to feminine women. Until now, I have examined the side of this spectrum where we find women who exhibit a physical or behavioural masculinity. In this section, I will briefly touch on the opposite side of the spectrum. As we shall see, Zahrtmann also painted a number of history paintings where women take on more feminine and conventional gender roles.

Such a female figure is found in a painting where Ullebølle served as the model of the Danish writer and translator Charlotta Dorothea Biehl (1731-1788) or, as Zahrtmann called her, Dorthe Biehl [fig. 18].46 SAs a historic figure, though, Biehl was far from an ordinary woman. She was the most prominent female cultural figure of 18th century Denmark. She is also said to be the first woman in the country who was able to make a living from her writing.47 During her lifetime, she wrote 13 comedies and singspiels, in addition to translating many works from German, French, Italian and Spanish. Biehl’s Historical Letters, a work about the kings Frederick V, Christian VI, Frederick VI, and Christian VII, provides some of the most important historical records of that time, although not all of the contents are equally accurate and credible.

Painted in the winter of 1874, this work was Zahrtmann’s second attempt with the motif and was exhibited at Charlottenborg the following year.48The first version, also from 1874, is marked by light colours, while the subsequent version is darker, giving the sense that something secret is going on. Furthermore, the furniture is arranged even closer to the writer, further accentuating her plump figure. It was not Biehl’s bourgeois, moralising and sentimental plays that provided the fodder for Zahrtmann’s portrait of her. Rather, he seems to have focused on the straightforward openness with which she relayed information about events within the royal court and behind the castle walls. Because of her more or less credible, but to a certain extent true stories, she was given the nickname “gossip bag”.49 The large woman in the painting is shown sitting at her window, watching the streets from above. In her mouth she holds a pen at the ready so that she can quickly record whatever she deems worthy of inclusion in her “historic gossip”.

The painting also seems more like a parody than a homage to an unusual and learned woman. Yes as with many of Zahrtmann’s history paintings, it appears to be open for the viewer to decide what is actually being parodied. Is it Biehl herself, or rather a special and conventional form of femininity? Most of Zahrtmann’s contemporaries seem to have pointed to the former. In 1893, the art historian Beckett wrote the following about the painting:

For a time the artist was greatly fascinated by the royal court’s tireless gossip, ‘Maiden Charlotte Dorothea Biehl’, whom he portrayed in a characteristic painting from 1874. The assiduous lady has left her writing at the desk for a moment, and with a goose feather pen in her mouth like a large hen, she sits in the window, where she pulls back the yellow curtain and curiously peeps out on the square. While she believes herself unobserved, we have the opportunity to observe ‘Sister Dorthe’ in a rather comic situation, heightened by her Junonian contours, and we see a corner of her room with a rose-wreathed painting of Frederick V above the Rococo desk, on which rests a coquettish Venus statue and a small piece of furniture with a haggard shepherd and shepherdess of painted porcelain.50

In his description, Beckett emphasises the comic nature of the contrast between the bombastic woman and the fine, rose-adorned interior. Among other things, he points to a Venus statue, which refers to a classic, female body ideal – an ideal from which the model Ullebølle deviates markedly. Whereas Zahrtmann’s painting of the Swedish Queen Christina presents a female masculinity to the viewer, this work instead presents an exaggerated female femininity. The large, almost supernatural hips and the many flowers and trinkets, combined with the interest in gossip and secrets, all point back to a bourgeois female stereotype.

Playing one’s own gender

Zahrtmann’s history paintings often give the impression that the figures are presenting themselves like actors on a theatre stage. This stage-like character is created by a back wall that is typically located close to the foreground and parallel with the image plane, while the figures are moved all the way forward in the foreground of the image. A few of the works even include a stage curtain, further emphasising the staging and dramaturgical nature of the paintings. One such example is Juliet and her Nurse from 1874 [fig. 19], a motif also taken from the theatre.51

The artist’s use of colour and light effects also contribute to creating this sense of theatre. Zahrtmann often uses a bright light – almost like a spotlight on a theatre’s stage – to illuminate the central figures. The figures also appear more realistic in their expressions, with relatively detailed colouring and shading, whereas the surroundings are typically more artificial and reminiscent of stage scenery with their strong colours and stylised contours. In other words, it seems clear that the surroundings are false, while the people appear more realistic.

The sense of acting is also found in Zahrtmann’s use of models. He frequently uses the same woman to model for numerous paintings. Nonetheless, these women remain recognisable in spite of the different roles they are playing. Zahrtmann cultivated the personal and characteristic aspects of his models; thus, his history paintings are not pictures attempting to recreate and represent figures such as Dorothea Biehlor Leonora Christina. Rather, these works portray a given person who is playing the role of a certain character. This sense of theatre and acting was discussed by many of Zahrtmann’s contemporaries. For example, in a letter to Zahrtmann, the painter Axel Helsted wrote the following about the painting of Aspasia for which Ullebølle had modelled:

[…] What does this old woman full of emotions tell of the time-honoured, proud Aspasia, who even in words you portray in such vivid colours – nothing! […] You have not printed the seal of credibility on the forehead of your Aspasia, and therefore she fails in that respect, but rises to extraordinary heights as an emotional, ordinary old woman in original costume with hand on a plaster bust of Hercules […].52

The sense of acting is particularly evident in a number of paintings where the model appears to be wearing the same clothing, but changes identity by virtue of the surroundings in which she is set, or the title given to the work. This is the case with a series of paintings portraying Johanne the Mad, Lady Macbeth, Queen Ingeborg and Marie Stuart [fig. 20-21]. Mrs. Mynzberg modelled for all four paintings, and in all of them she wears the same white dress with different degrees of variation, and with the same hairstyle. The great similarity between the four female characters was the subject of extensive critique by contemporaries, as it spoiled the historical illusion for the viewer. Regarding two of the aforementioned paintings, which were exhibited at Den frie Udstilling in 1900, writer and poet Sophus Michaëlis wrote:

Most significant of our own ‘literary’ art are Zahrtmann’s paintings ‘Queen Ingeborg mourns by the corpse of her 14th child’ and ‘Lady Macbeth’. If the paintings had appeared separately so that their use of the same model, which even extends to the same clothing, had not been so irritatingly obvious to the viewer, the effect would have probably been much stronger. Both paintings are so thoughtfully conceived and breathtakingly executed in their portrayal of, respectively, the lust for power and the grief of a mother. But the painterly means, the language is far too much the same. Lady Macbeth and Queen Ingeborg should not be speaking the same tongue, the same poetic diction.53

The model similarity is most pronounced in the works Hotel de Ville in La Rochelle. Justitia and Misericordia meeting each other from 1895 [fig. 22] and Socrates and Xanthippe (1895: Private collection), which portray an almost identical female figure dressed in green. In one work, she appears as the righteous Justitia, while in the other she takes the role of Socrates’ ill-tempered wife, Xanthippe. In these works, even the posture of the figures is the same. Zahrtmann simply added a small scale in the hands of the woman in the first mentioned work and made minimal adjustments to her dress.

Zahrtmann’s method is also closely aligned with the overall theatricality that seems to imbue his history paintings, a method that is rooted in something actually seen. He had to have the living model and the physical things in front of him when he painted – even when it came to smaller things like silver platters and the model’s attire.54 The paintings are thus based on a live staging, a kind of theatrical work performed in the artist’s studio and then reproduced in a two-dimensional expression on the canvas. Zahrtmann’s studios thereby became venues or stages where the various historical events, mythological and biblical stories, and various female roles were re-enacted.

In many respects, Zahrtmann’s history paintings incorporate and build on the entertainment industry’s visual strategies and techniques. First and foremost, they are works that draw one’s attention at an exhibition. The history paintings are often painted in bold colours, demanding attention and exuding an insistent – almost intrusive – presence. Furthermore, many of the paintings are large in size, giving them a notable physical presence in the room. For example, the painting of Queen Christina in Palazzo Corsini measures 105 x 152 cm, while the painting of Fenja and Menja measures 141 x 107 cm. The works also often possess a certain entertainment value, as they portray gender in a humoristic manner.

Through his use of models, composition, painting technique and colours in his history paintings, Zahrtmann seems to emphasise the theatrical and thus the artificial. In that way the gender and identity of the figures are not presented as something inherent by nature, but rather something constructed and performed. Zahrtmann transcends the gender roles of the time by the mere act of defining them as roles. In his works, the same recognisable woman can represent many different kinds of femininity. For example, Mrs. Mynzberg is everything from a gentle and beautiful Shakespearean maiden [fig. 19] to an evil, frightening and old Lady Macbeth [fig. 20]. Meanwhile, models who are biological males can become female figures by virtue of the title of the paintings and by modifications to their appearance [fig. 8 and 12]. Thus the biology of the models does not define who or what they are, but rather their actions.

This theatricality in Zahrtmann’s works can today be viewed in the light of American queer theorist Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity. According to Butler, gender is comprised of roles that the individual continuously embraces and performs to gain acceptance within a particular discourse. Gender is not something we are born with, but something we do. It is the actions we learn within a cultural and social context.55 Zahrtmann’s works seem to epitomise this performative nature of gender nearly 100 years before it was encapsulated in academic theory.

In queer theory, parody and exaggeration are strategies used to transcend gender roles and expose them as artificial, unnatural and constructed. These strategies can also be found in Zahrtmann’s history paintings of women, who often portray gender in an exaggerated and parody-laden manner. However, parody in itself is not a subversive or transcendent act; this depends on its cultural context and reception. Thus, a distinction can be made between a normalising and a disrupting parody.56 Zahrtmann’s paintings contain both types of parody at once, and he leaves it to the viewer to decide on how the parody is perceived. In this way, Zahrtmann manages to be both in accordance with and in opposition to the gender norms of his time.

The history painting as a space for exploring gender and sexuality

It is interesting to note that unusual, masculine women repeatedly appear in Zahrtmann’s history paintings, while they are all but absent in the artist’s works within other genres. For example, his genre paintings from Italy are largely in line with the bourgeois gender patterns of the time, typically depicting men observing women, who giggle about being observed (by men); these women often have conventional feminine roles such as housekeepers and childminders.57 It seems that the history painting offered Zahrtmann a space with a much greater potential for exploring gender and sexualities.

It seems that the history painting offered Zahrtmann a space with a much greater potential for exploring gender and sexualities. In the traditional sources of history paintings, Zahrtmann found a wide array of motifs touching on these very subjects. The figures portrayed are often historical, mythological or biblical persons who broke with the norms for gender, or who are parts of stories in which gender and sexuality are the main focus. For example, Zahrtmann painted numerous works depicting Caroline Mathilde and Struensee that refer to their sexual affair and the queen’s infidelity. He painted Susanna in the bath, a biblical tale of a woman who is spied on by two old men, and who is accused of infidelity. He painted Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth, who in the play is described as masculine, and who also explicitly states that she wishes that she were a man. And he painted the Swedish Queen Christina, who was also considered to have a masculine appearance and who radically broke with the norms for the female gender in her time – and the list of similar figures goes on.

The history painting also enabled Zahrtmann to comment on events or circumstances of his era. According to the British art historian Imogen Hart, European artists during this period used history paintings in a way that allowed them to subtly engage with contemporary issues by utilising the genre’s ability to contain multiple layers of meaning. Instead of commenting directly on contemporary issues, they commented on the conditions while maintaining what Hart calls “the distance of metaphor”. With the aid of this historical distance, it was much easier for the history painters of this era to relate to current issues that would have otherwise been impossible to address in their art.58 In the case of Zahrtmann, these issues were gender roles and sexuality.59

Furthermore, it is interesting that Zahrtmann uses the history painting as a framework for alternative female roles, as it is traditionally a patriarchal, heteronormative genre closely linked with academic conventions. History painting was traditionally reserved for male painters, and typically one or more men were given the main roles in history paintings.60 For much of the 19th century, history painting was the most ambitious form of painting, and one of the most highly esteemed genres a (male) painter could work with. It required something of both the painter and viewer, who would have to be familiar with the literary works and historical events illustrated by the motifs. History painting also played the role of exemplum virtutis, providing an example of virtue, raising it to a moral guide and source of universal truth. Accordingly, history painting was called ‘the great art’, as opposed to landscape, portrait and genre painting, all of which were further down in the academic hierarchy of genres.61

Zahrtmann seems to utilise the formerly privileged position of history painting as the paramount task of art and artists when he gives unusual women with different or ambiguous gender identities the main role as important historical, mythological or biblical figures. His history paintings offer alternative versions of history that build on a different approach to gender than the heteronormative, where the status of ‘abnormal’, masculine women becomes that of something ideal.

Thank you

The author wish to thank Michael Hatt, University of Warwick, and Patrik Steorn, Thielska Galleriet, for inspiring conversations and discussions about Zahrtmann’s art. A special thank you to Rasmus Kjærboe, Ribe Art Museum, for guidance and inspiration during the making of this article.