Summary

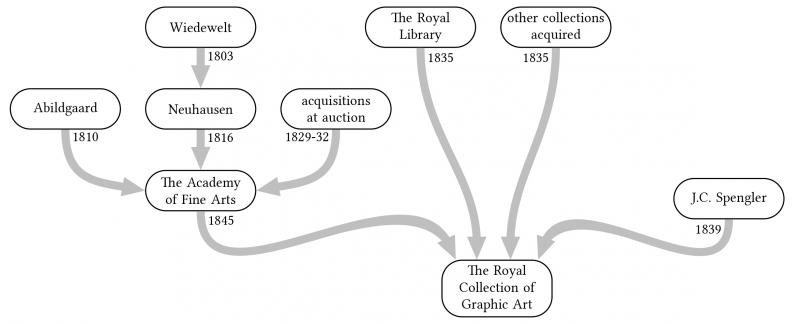

Even before there was talk of a central collection of drawings and fine-art prints – what would eventually become the Royal Collection of Graphic Art in 1835 (Den kgl. Kobberstiksamling, formerly known as The Royal Collection of Prints and Drawings) – Danish drawings were already being collected on a grand scale. During the period 1810 to 1832, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts built a large collection of recent Danish drawings, and the director of the Royal Picture Gallery, J.C. Spengler, personally collected sheets by older artists. This article delves into the history of these two predecessors of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art and how they impacted the overall definition and perception of Danish draughtsmanship.

Articles

In the early nineteenth century, Denmark had no main, central collection of drawings. The Royal Reference Library supposedly held a number of drawings which were all lost in the great fire of Christiansborg Palace in 1794.1 Another collection of drawings could be found as part the large collection of graphic arts in the greater Royal Library, but this collection was never (or only very rarely) added to and suffered a rather languished existence overall. Tellingly for the state of the greater Royal Library’s collection, any new royal acquisitions of drawings were not handed over to the library’s care, but placed in rented rooms in the nearby street Frederiksholms Kanal.2

After years of deliberations, in 1835 the various royal collections of graphic arts and drawings were finally merged in a new, independent institution called Den kongelige Kobberstiksamling (The Royal Collection of Graphic Art).3 [fig. 1] This event is well chronicled in art history, but what has escaped attention so far is how the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts sought to place themselves in a position to take over these collections while their future was as yet undecided. One of the methods used to further this endeavour seems to have consisted in efforts to obtain a representative collection of recent Danish drawing. Ultimately, however, the Royal Collection of Graphic Art became a reality, an institution which would from then on strive to be the nation’s primary collection of, among other things, Danish drawing. If the Academy’s collections of drawings was the main institutional predecessor of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s Danish collection, the most important lump addition was made in the form of the acquisition of a private collection: the large collection of drawings built by Johan Conrad Spengler (1767–1839), who was director of the Royal Picture Gallery. His collection would prove to set the tone for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, determining its future progress.

Research into the provenance of objects not only aims to chart the history of ownership of a given artefact; it can also give us deeper insight into the principles and assumptions that live on implicitly in, for example, the principles underpinning the collection activities of museums. By awarding the Academy’s and Spengler’s separate collections of Danish drawings their due place within Danish museum history, we may also shed some light on how Danish draughtsmanship was defined and perceived back when the museums and the discipline of art history were still in their infancy. No methodical research has ever before been conducted into the provenance of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s oldest stock of Danish drawings. What follows constitutes the first attempt at depicting the main sources of these two collections. This undertaking has required a time-consuming, painstaking review of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s Danish drawings from before 1840, comparing inscriptions, subject matter and other characteristics up against written sources such as inventories, sale catalogues and correspondence in order to identify, if possible, each individual drawing’s history of ownership – thereby ultimately reaching the roots of our present-day national collection of drawings.

1810–16: The Academy begins collecting

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts had built a somewhat haphazard collection of art on paper. Parts of the collection of prints may date back to the oldest incarnation of the Danish art academy, directed by the painter Hendrik Krock (1671–1738), but it appears that additions to the collection were made only rarely, and that it included virtually no drawings. The first substantial addition took place in 1810 with the purchase of the late Nicolai Abildgaard’s (1743–1809) books, drawings and prints. The painter’s modest collection of drawings encompassed only thirty-seven sheets; however, these were attributed to very prominent figures such as Raphael, Titian, Rembrandt and Poussin.4 The collection featured only a few Danish sheets, including some copies after Raphael executed by Abildgaard himself and a few drawings attributed to Marcus Tuscher (1705–51) and Karel van Mander III (circa 1609–70).5 The purchase also included a much larger collection of prints, but sadly the exact contents of this collection are not documented.

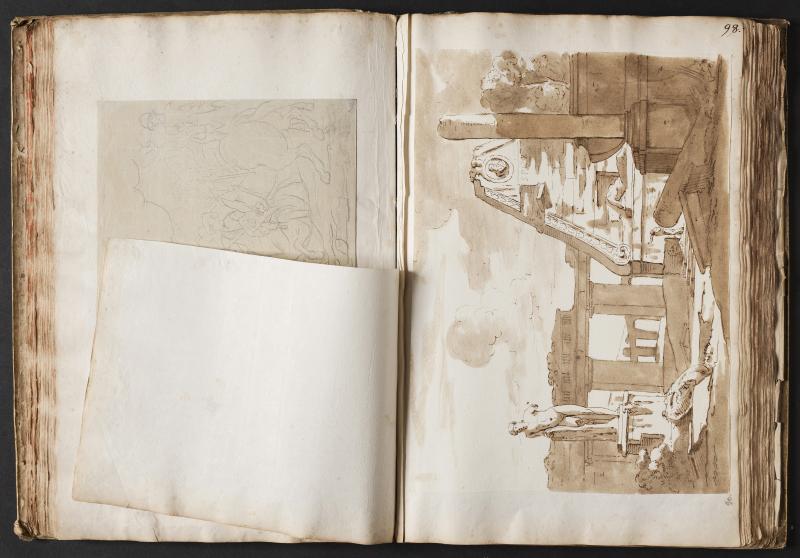

More spectacular was the collection bequeathed to the academy by the master artisan painter Jens Neuhausen (1774-1816) upon his death. The bequest is described in detail in a surviving probate record, where it is shown to have encompassed (in addition to a quantity of prints) almost 3,000 drawings, primarily by Johannes Wiedewelt (1731–1802).6 Neuhausen acquired most of his drawings at the auction of the estate of the late sculptor in March of 1803, and since then they had served him as inspiration and source material for his many assignments as a decorative painter.7 A committee comprising the academy secretary and five academy professors were in charge of selecting the works the Academy would be interested in receiving. And even though some albums featuring drawings of an artisanal nature and most of the prints appear to have been winnowed out on this occasion, the Academy was nevertheless left with an unexpectedly fine collection that merited further expansion. An inventory from 1821 tells us that the Academy’s collection of drawings held no less than 2,341 sheets at that point.8 In addition to 29 foreign drawings from Abildgaard’s collection, the Academy owned nine unidentifiable sheets by Italian masters, approximately ninety sheets by German masters (which were in fact Mengs and Casanova) and no less than 2,214 Danish sheets.9 Most of these were by Johannes Wiedewelt, but the collection also encompassed smaller groups of drawings by Abildgaard, Marcus Tuscher, Carl Frederik Stanley (circa 1738–1813) and Johan Mandelberg (1730–86).10 This should be compared to the Academy’s collection of graphic art, which comprised 1,560 loose sheets at the time. Of these, 472 had been purchased as part of Abildgaard’s collection, whereas almost 150 were added as part of Neuhausen’s bequest.11 The idea of having a collection of drawings, first introduced with the acquisition of Abilgaard’s collection, had now been realised with Neuhausen’s present. In one swoop, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art was on its way to becoming a centre for recent Danish drawing.

1826-29: Plans to transfer the royal collections of prints to the Academy

In the 1820s, regret at the absence of a single primary public collection of prints was expressed from several quarters. In his 1821 review of the nation’s art collections, Frederik Thaarup said: ‘It would be capital if we had, as they do in Vienna and Dresden, a cabinet of prints where artists and art amateurs could, at specific times and in premises designed for this very purpose, study such art’.12 However, it was only when the Holstein art historian, baron Carl Friedrich von Rumohr (1785–1843) and the young library secretary Just Mathias Thiele (1795–1874) went over the old albums of mounted engravings five years later that the library’s management became truly aware of the critical condition of the collection and its hopeless lack of any systematic order. The opening of the Royal Picture Gallery [Det kgl. Billedgalleri] at Christiansborg in 1827 further fuelled the speculation and desire to impose order on the royal collections of prints and drawings and make them accessible. For example, in the summer of 1827 a well-informed reviewer expressed hopes that ‘the rich collection of engravings that is currently part of the greater Royal Library […] [might] soon have a knowledgeable, skilled hand bring upon the same good fortune [being made accessible for academic study]; for only then would it be truly useful, and it might then, under independent management, be affiliated with the Royal Picture Gallery’.13

The librarian Erich Christian Werlauff (1781–1871) supported the idea of merging the different collections and the newly established picture gallery, even if he also saw the advantages inherent in the alternative plan to transfer the library’s collections of graphic art to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.14 The latter idea originated with the library’s director, titular prime minister Ove Malling (1748-1829), and to Werlauff’s mind it had the advantage that the library would be likely to receive fiscal compensation from the Academy. Hence, negotiations concerning a sale of the collection were opened in 1828.15

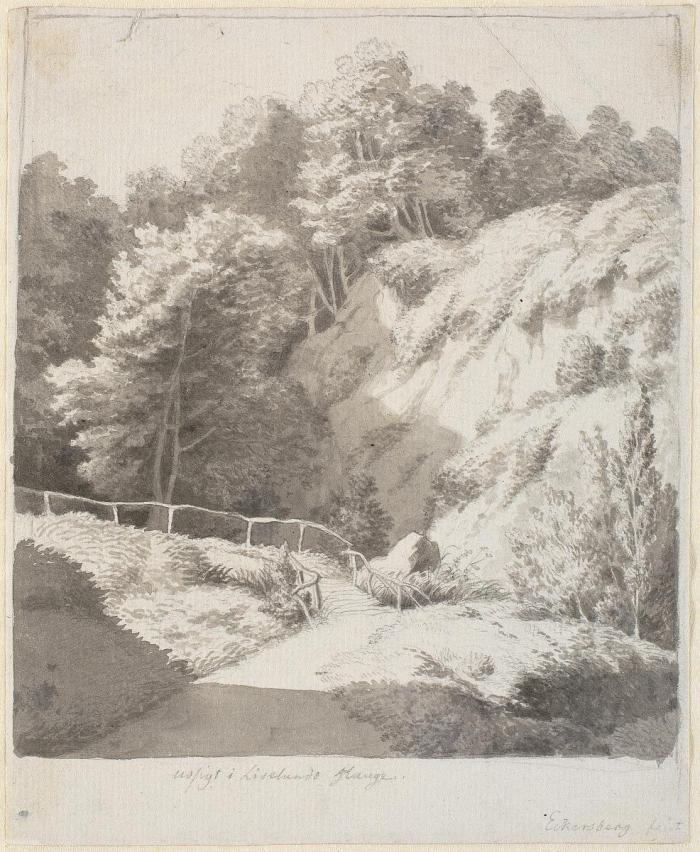

With the library director’s proposal and the librarian’s initial blessing, the Academy now spied a major endowment of art on the horizon – although there was a clear risk that it might have to be paid for. It is unlikely that the academy assembly would allow this opportunity to slip away, and it would appear that work was being done behind the scenes in order to promote such a transfer. Presumably seeking to build up arguments why the royal collections of art on paper should be reallocated to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ library, the Academy now embarked on a programme of acquiring Danish drawings. The first focused acquisitions were made at the auction of the estate after Johan Bülow, held on 13 to 22 April 1829. Ahead of this auction the academy assembly had decided to set aside funds for the purchase of drawings, and the landscape painter Jens Peter Møller was appointed to act on the institution’s behalf in this matter. Møller was particularly successful in acquiring a large number of preliminary studies for illustrations, but also got hold of many other sheets, most of them fully finished. In one case he was even able to correct an erroneous attribution: he brought home a watercolour that the author of the auction catalogue, Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, had listed as a work by the animal painter Christian David Gebauer, but which Møller recognised as a work by his close friend C.W. Eckersberg.16 Thiele – who in addition to being employed at the Royal Library also acted as librarian and secretary to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts – could now, acting on behalf of ‘Akademiets Kunstsamling’ [the Academy Art Collection’], receive drawings by e.g. Mandelberg, Stanley, Peter Cramer, Cornelius Høyer, C.F. Hansen, Abildgaard, Jens Juel, Johan Friedrich Clemens, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Gebauer, Johan Ludwig Lund and Eckersberg.17 [fig. 2] Summing up, steps had been taken to supplement the existing collection with a small, but reasonably representative group of recent Danish drawings and to make it abundantly clear that the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts had the means necessary to make focused additions to the collection through purchases. The cornerstone had been firmly laid for the first institutional collection of Danish drawings.

1829–35: The tide turns

In November 1829 the head of the Royal Library, Ove Malling, died, leaving the fate of its graphic art blowing in the wind again for a while. He was succeeded by Chief Lord Chamberlain [overhofmarskal] Adam Wilhelm Hauch (1755–1838), who was prepared to separate out the library’s collections of engravings, but chose to consult with more experts before an actual plan was presented to the king. It would seem that little progress had been made towards an actual decision a year later when Andreas Christian Gierlew, in December 1830, offered the library his collection of Italian drawings. J.C. Spengler, director of the Royal Picture Gallery, recommenced the purchase, which would ‘undoubtedly be a favourable acquisition if one were ever to be inclined to replace the large and costly collection of drawings that perished in the fire of the Royal Reference Library at Christiansborg’.18 Hauch for his part excused himself by pointing to the nation’s empty coffers, which made it entirely unfeasible to ‘complete the current, rather insignificant collection of drawings’.19

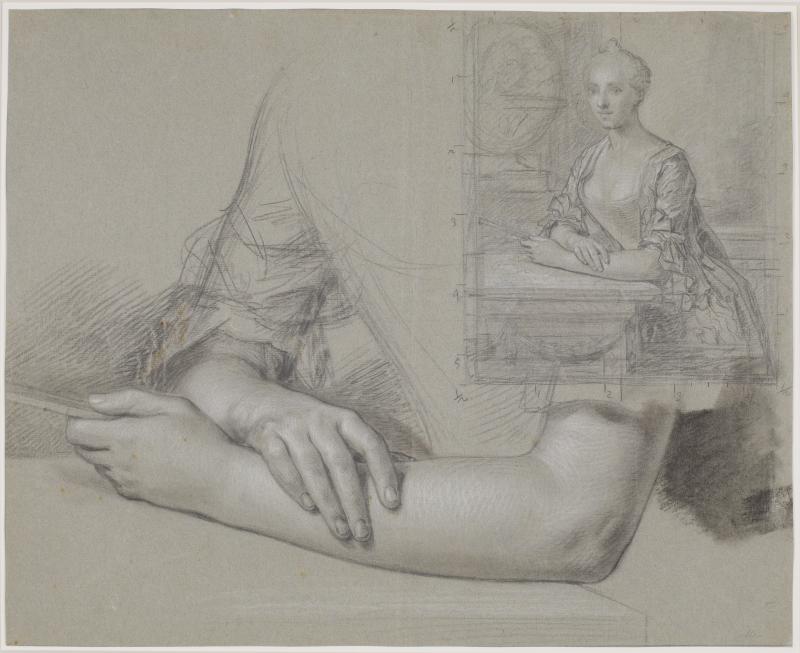

In the meantime Christian Jürgensen Thomsen had submitted the requested memorandum. In this document he advised against leaving the systematisation and expansion of the collections to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.20 Instead he suggested that all of the royal collections of drawings and prints should be combined in an autonomous institution – a model that reflected Thomsen’s visionary endeavours to make the royal collections accessible as a range of specialised scientific collections. Thomsen’s ideas were taken on board in the final proposal that Hauch presented to the king, Frederik VI, in March of 1831, and in April the final decision was reached: the collection of drawings was to be separated out from the Royal Library.21 While this meant that the idea of transferring the collections to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts had been shelved, the Academy could still reasonably regard itself as a potential candidate for having the nation’s primary collection of Danish drawings. As a result, the Academy continued to purchase Danish drawings for a while yet. For example, at the auction of the estate after the engraver Johan Friedrich Clemens on 1 May 1832, the Academy acquired a group of excellent drawings by Jens Petersen Lund, Abildgaard, Clemens, Juel and others.22 [figs. 3-4] However, before the decade had come to an end, the Academy had also been outmanoeuvred by the competition on this score.

1835–41: Reinforcing the Royal Collection of Graphic Art

In 1835, most of the Royal Library’s collection of prints was separated out, other collections were taken from the royal castles and palaces, and Just Mathias Thiele was able to resign from the library and take up his new position as curator of the newly established Royal Collection of Graphic Art (Den Kongelige Kobberstiksamling). At this point the collection was still short on Danish drawings. However, the portfolios holding the collections of Lambert van Haven and Lorenz Spengler did contain a number of older sheets that could reasonably be thought to belong to the Danish school. From the latter collection, Thiele was able to pick out a score of drawings by artists who had immigrated to Denmark such as Heinrich Dittmers (1625–77), Jacob d’Agar (1642–1715) and Benoit le Coffre (1671–1722), as well as twenty-eight sheets by Mandelberg, eight by J.P. Lund and another score of sheets by Spengler’s good friend, the German-born artist Marcus Tuscher [fig. 5]. But apart from these works it would, as far as drawings were concerned, be difficult to lay claim to having a Danish section in the newly founded institution. The stock of drawings representing the period after 1750 was the most deficient of all, and one of Thiele’s main priorities was to remedy this lacuna.

The best opportunity to do so came with the death of J.C. Spengler in 1839. Spengler certainly took after his father: over the course of the preceding forty years he had built the largest collection of drawings in the nation. Spengler’s drawings by foreign artists were put up for auction, attracting an entirely new circle of Copenhagen-based collectors, and Thiele also availed himself of this opportunity to make major purchases for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art.23 However, Thiele would not permit Spengler’s collection of Danish drawings to be scattered to every corner of the world, and on this point he won the media’s support. Just a few weeks after Spengler’s death, a contributor to the newspaper Kiøbenhavnsposten called attention to his ‘collection of drawings by Danish masters, the only one of its kind, and a collection on whose completion he spared neither time, care nor expense. We hope that the State will seek to acquire this collection, thereby ensuring that what has been so carefully brought together should not again be torn asunder’.24 It is possible that Thiele authored this piece himself, for when Spengler’s heirs finally offered to sell the collection to the king in the summer of 1840, Thiele recommended the purchase in similar terms. On this occasion he praised Spengler’s ‘important collection of drawings by Danish masters, given that it is the only one of its kind and would be a significant embellishment [of] His Majesty’s collection of prints and drawings’.25 Thiele concluded by emphasising: ‘I should be remiss in failing to give this my warmest recommendation as a favourable opportunity that will in all probability never again be seen in this country’. The purchase had been made by December.

Spengler’s collection of Danish drawings comprised more than 1,700 sheets and was arranged to provide an historic overview of almost three hundred years of drawing, from Melchior Lorck [e.g. fig. 6] to C.W. Eckersberg.26 The collection is not only distinguished by its extent, but also by its high quality overall and by its representative selection of eighteenth-century art in particular. Especially striking were the collection’s many large-scale sheets, such as Jacob Coning’s scene from the gardens behind Charlottenborg, Magnus Berg’s Apotheosis of Christian V [fig. 7] or Peder Als’s beautiful studies for portraits.27 [fig. 8] However, the collection also included less formal, sketch-like sheets, many of which were regarded as having limited artistic merit at the time.28 Less famous artists and Spengler’s younger contemporaries were usually represented by just a few sheets, and conversely Spengler had acquired dozens of drawings by the more prominent figures. For example, he owned fifty-eight sheets by Peter Cramer, eighty sheets by Christian August Lorentzen, eighty-six sheets by Jens Juel [including fig. 9] and no less than ninety-six sheets by Abildgaard. Even today, most of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s drawings by Cramer, Juel and Lorentzen, as well as by Karel van Mander III, Vigilius Erichsen and Alexander Trippel, come from Spengler’s portfolios.

1845: Exchanging drawings with the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts

The purchase of J.C. Spengler’s collection would form the basis of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s Danish collection and firmly established it as the main institution for Danish art on paper. At the official opening of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art in April of 1843, Thiele was able to present a splendid and reasonably representative collection of Danish drawings.29 Even so, Thiele had by no means forgotten the Academy’s ventures into establishing an art collection; an endeavour which he himself oversaw in his continued capacity as academy librarian. In 1845 he brought about an exchange between the two institutions where the Academy transferred a large number of works to the Royal Collection of Graphic Art. This exchange included all of the Academy’s most valuable engravings, the entire Abildgaard collection of drawings, and most of the sheets bought at auction. [including figs. 2-4]

However, not every Danish drawing in the Academy’s collection was transferred. Perhaps out of veneration for Neuhausen and his bequest, the drawings by Wiedewelt, Tuscher and Mandelberg remained in the Academy’s ownership. Strangely enough, the Academy also kept an album of Mandelberg drawings that did not come from Neuhausen’s collection, but which J.P. Møller had bought at the auction of Johan Bülow’s estate in 1829 on behalf of the Academy. The album originally held 173 drawings, but Bülow added another couple of hundred sheets to this number.30 Prior to the auction, Møller agreed to share the drawings with J.C. Spengler, who cut out 186 sheets.31 [fig. 10] Many of these drawings must have been included in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art alongside Spengler’s Danish collection, and perhaps this prompted Thiele to regard the collection as being amply stocked in this regard, causing him to leave the actual album at the Academy.32 Or perhaps, amidst all the commotion, someone other than Thiele assumed that the album was part of Neuhausen’s bequest? Many years would pass before another large portion of the drawings still held at the Academy were transferred from its library to the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, meaning that today, the Wiedewelt drawings are all that is left of Neuhausen’s bequest in the Academy collection.33 However, these later transfers are mere footnotes in the overall narrative – the 1845 changeover unequivocally established the fact that the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts had in effect lost any real claim to being a potential centre for the collection of Danish drawings.

The Danish collection in 1845: Subject matter

The acquisition of Spengler’s collection had a major influence on the study and overall perception of Danish draughtsmanship, and its contents would have a crucial impact on the nature of the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s Danish collecting activities for decades to come. If we look at the subjects and themes represented in Spengler’s Danish drawings, we find the outline of a collection amassed in order to illustrate the history and art history of the nation, but also of a collection that reflected Spengler’s own position and outlook on the world. For example, in some respects Spengler’s Danish collection became a kind of inverse monument to what may have been his greatest achievement of all: the heroic evacuation of a large number of paintings during the palace fire of 1794.34 In the decades that followed, he succeeded in collecting a range of preliminary studies for many of the paintings that could not be rescued due to their size or because they were embedded into the architecture, causing them to perish in the flames. For example, he owned a group of figure and costume studies for one of Abildgaard’s paintings in the Great Hall of the palace,35 and he had an ‘exceptionally lovely drawing’36 created as a preliminary work for Marcus Tuscher’s painting King Christian VI is hailed by Denmark and Norway. The fact that this part of the collection was carefully planned and arranged to serve as documentation for the works that went up in flame is accentuated by the fact that Spengler’s modest collection of paintings included a scaled-down version of Karel van Mander III’s equestrian portrait of Christian IV, which had also been lost in the palace fire.37

Overall, Spengler’s collection held a remarkable large number of drawings depicting Danish kings and their exploits, including a series of studies for monumental equestrian portraits or statues. It would seem that in this respect Spengler continued along lines laid down by his father: the elder Spengler’s collection had included Marcus Tuscher’s proposal for an equestrian monument to Frederik V in the square of the Amalienborg complex and the same artist’s very carefully finished drawings for the painting of the mounted king Christian VI and for an intended pendant piece depicting Frederik V.38 In 1812 J.C. Spengler described the latter sheets as ‘the loveliest drawings ever executed in ink’.39 The younger Spengler continued these collecting activities, and in addition to the works by Tuscher and van Mander he believed himself to own drawn designs for e.g. Abraham César Lamoureux’s equestrian statue of Christian V and Saly’s ditto of Frederik V.40

Spengler’s collection also included a number of drawings showing scenes from recent Danish history, such as a large watercolour of the Liberty Column [Frihedsstøtten] raised in 1797 to commemorate the abolition of adscription in 1788 as well as Eckersberg’s aforementioned depictions of the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807.41 And it held a number of illustrations for Danish literature, such as Clemens’s illustrations for Holberg’s plays after designs by Abildgaard.42 Spengler had only limited interest in folk scenes, and rural series such as Johan Gottfried Grund’s four designs for sculptures for the Nordmandsdalen sculpture park were rather drowned out by more sophisticated city types, such as Johannes Senn’s twenty-four drawings for Klædedragter i Kiøbenhavn [Copenhagen Costumes].43 The closest thing to folk scenes and themes in Spengler’s collection would be drawings featuring scenes of national heroics made particularly famous by Ove Malling’s Store og gode Handlinger af Danske, Norske og Holstenere [Great and Good Deeds by Danish, Norwegian and Holstein Men] [e.g. fig. 11].

Like his art historical writings, J.C. Spengler’s letters from his Grand Tour abroad in 1787–90 testify to his classicist outlook on art.44 It is hardly surprising, then, that his collection was also aimed at showcasing the Danish artists’ ability and willingness to pick up the mantle from their ancient forebears. Perhaps the many royal equestrian portraits should be considered in this light, but the collection also included studies of ancient sculptures and ruins by e.g. J.P. Lund and Mandelberg, architectural drawings by C.F. Hansen and Harsdorff, and a large number of drawings by neoclassical artists such as Wiedewelt and Alexander Trippel.45

The Danish collection in 1845: Danishness

The way in which Spengler’s collection had been conceived, perceived, collected and arranged also had a major knock-on effect on the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s overall direction as the main collection of Danish art on paper. We do not know for certain when Spengler arranged his Danish collection as a separate entity. In his earliest handlist from around 1820–23, a total of 239 Danish drawings still appear amidst the drawings made by artists from abroad, but by the late 1820s the Danish drawings had been separated out from the rest and were kept in three folders dedicated to this purpose.46 This is to say that the idea of forming a separate national collection can be plausibly assumed to have arisen at some point during the 1820s. An obituary makes the following statement about the thoughts underpinning the collection:

At a time when an interest in drawings was more rarely seen in this country than now, and when our art history was as yet quite untreated, Spengler made the praiseworthy decision of seeking to collect what might yet be found in this country of studies and drafts by artists who can, by virtue of their birth, works or sojourns here be included in Danish art history. 47

In his collection activities Spengler took a pragmatic approach to nationality, regarding as Danish any artist who had studied or worked in Denmark, Norway and/or the duchies. Of course this included his own father, Lorenz Spengler, who had arrived in Denmark from Switzerland in 1743 and was represented in the collection by nine drawings.48 This also held true for several visiting artists dating back to the seventeenth century, such as Johannes Glauber, to whom Spengler attributed the aforementioned view of Charlottenborg. And the list included the foreign academy professors and students of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries such as Saly, Pilo, Asmus Jacob Carstens, Caspar David Friedrich and Johan Christian Dahl. [fig. 12] Several of the artists featured in Spengler’s Danish collection had only very tenuous links to Denmark – most remarkably Louis Tocqué, who only spent seven months in the country, but was nevertheless represented in the collection in the form of a beautiful compositional sketch.49 Sergel was also represented by a handful of drawings even though his stays in Denmark were few and of brief duration.

The definition of Danishness was one point where the Royal Collection of Graphic Art came to differ significantly from the Royal Picture Gallery at Christiansborg Palace. Under Spengler’s management, the gallery’s Danish section had – like his private collection – comprised a mixture of native and visiting artists. After Spengler’s death, Niels Lauritz Høyen took a different approach, launching a definition of a national school in which he put much greater emphasis on the artists’ place of birth when defining their proper place in art history.50 However, Høyen’s thinking fell on stony ground at the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, where Thiele (presumably partly for practical reasons) chose to keep Spengler’s system. For this reason, the handwritten catalogue of the collection from 1858 includes the following note about the Danish section: ‘this collection of Danish drawings was mostly collected by the late Lorenz [actually Johan Conrad] Spengler and upon its acquisition included in the royal collection according to his catalogue. For this reason, the collection includes works by certain foreign artists who have not been separated out’.51 While Høyen’s outlook on art required artistic homogeneity and a clear-cut overall aesthetic sensibility if one were to speak of a national school of art, Spengler’s view of Danishness was based entirely on historical facts. This meant that Spengler’s perception of Danish art history not only could, but had to, accommodate a greater diversity of stylistic modes of impression, conflicting trends and short-lived movements. In brief, Spengler’s collection activities (and his hang of the Danish room at the Picture Gallery too) were not so much about Danishness as they were about documenting all the different modes of expression that had been cultivated in Denmark and the various inputs and inspirations that the Danish art scene had received from abroad through the ages.

The Danish collection in 1845: Views on history

The Royal Collection of Graphic Art also pursued a different path than the Royal Picture Gallery in its approach to collecting contemporary art. Once again, one of the factors influencing this difference was the outlook on art imported with the purchase of Spengler’s Danish collection. Writing about Spengler’s views on contemporary art, his nephew wrote that ‘he, who had been a contemporary of Abildgaard, Poulsen and Cornelius Høyer, was rather strict in his judgments as far as Danish art was concerned and did not rank the current generation of artists as highly as they believed they deserved […]’.52 At Spengler’s death his Danish collection included only a few drawings by artists who were living at the time: J.L. Lund, Ernst Meyer and Adam Müller were each represented by two sheets each, as were Bertel Thorvaldsen, by whom Spengler owned a highly finished presentation drawing [fig. 13]. Only Eckersberg was more extensively represented than they, but even in his case Spengler had only bought very carefully finished drawings – mostly designs for engravings – which also happened to date back several decades. For example, the Royal Collection of Graphic Art received five of the painter’s early views of Copenhagen and three scenes from the wars against England – and all these drawings had been obtained at the auctions of the estates of the engravers Clemens and Lahde held in 1832 and 1834, respectively.53 There was, then, little contemporary art in the strict sense of the term in Spengler’s collection, and following its acquisition by the Royal Collection of Graphic Art, Thiele actually made a point of only acquiring drawings by late artists.54 As a result, the stock of recent drawings from the Academy’s and Spengler’s collections was only substantially expanded as the ‘Golden Age generation’ gradually passed away. Even though this may seem like a rather hesitant acquisition strategy, the head of the collection was often successful in buying wisely and in bulk whenever the opportunity arose with the death of an artist. Through acquisitions from the estates of e.g. Christen Købke (1848), Martinus Rørbye (1849), Johan Thomas Lundbye (1851) and C.W. Eckersberg (1854), Thiele and his successors built a Danish collection which was, at the turn of the century, probably more fully representational than the Danish section of the Royal Collection of Painting.

While the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art’s early overtures towards establishing a public collection of Danish drawings was soon consigned to oblivion, the Royal Collection of Graphic Art had, by the early 1840s, completely taken over as the primary public collection of Danish drawings. Among artists, it soon became natural to think that their sketches and studies might be of national significance and institutional interest. So when Johan Thomas Lundbye pondered the matter of his earthly possessions ahead of his Grand Tour abroad in 1845, it was natural for him to wish that ‘the drawings should not be separated if they could become part of some public collection’.55

As has been demonstrated, J.C. Spengler’s collection was particularly instrumental in setting the tone and standards for the Royal Collection of Graphic Art’s subsequent collecting activities and organisation. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the definition of Danishness used by Spengler grew widespread among art historians as well as in wider circles. This was not least due to the work of the art historian Philip Weilbach (1834–1900), who used a similar definition of Danish art history in his art encyclopaedias: now, artists could once again be regarded as Danish if they had ‘lived and worked in Denmark or within the Danish state’.56 By contrast, most of Spengler’s other principles for the content and organisation of his Danish collection were subsequently revised: the principle of never buying works by living artists has been departed from since 1912, and a comprehensive restructuring undertaken in the 1960s also disbanded his alphabetical system.57 But even though drawings by artists such as Tocqué and C.D. Friedrich have, quite correctly, been transferred to the sections for foreign artists, the historic definition of an artist’s Danishness has survived ever since the collection was founded. Perhaps the national collection of drawings found in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art has ultimately had the final word on the matter, winning out against the Picture Gallery’s rather more one-sided presentation of Danish-born artists. ▢