Summary

Anna Ancher’s painting A Vaccination from 1899 is an unusual subject within the artist’s own oeuvre and in Danish and Nordic art in general, which has only a few examples of works dealing with this theme. The work is often interpreted as an example of experimentation with colour and light and as depiction of everyday life in the Skagen community. But what happens if it is placed and considered in a context focusing on other contemporary depictions of health-promoting initiatives? Taking its starting point in Ancher’s painting, this article takes a closer look at how advances in public health promotion and disease prevention were portrayed in the late nineteenth century.

Articles

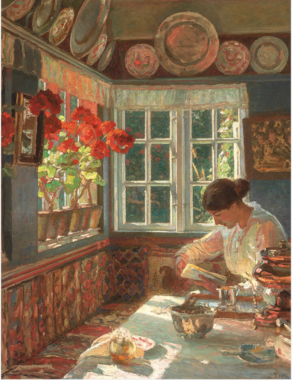

In 1899, Anna Ancher (1859-1935) painted A Vaccination, exhibiting it at the annual juried Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition that same year [Fig. 1]. At the time the painting was well received by critics, who particularly noted its colours, the amusing subject matter, the virtuoso depiction of everyday life and not least the fact that Ancher had sold the picture to a private collector at a relatively high price before it was even exhibited.1 However, none of the Danish reviewers commented on the fact that with this choice of subject matter, Ancher inscribed herself among a range of nineteenth-century artists, especially from France and England, who painted vaccination scenes. These were exhibited in several places, including the Paris Salon and at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889. Nor did the reviewers note that the painting can also be seen as a work that addresses public health and the safeguarding of future generations, meaning that it can be placed within the context of other art from the era which focuses on the prevention and treatment of disease.

There is much to suggest that Ancher was inspired by a French artist when she painted the picture, but unlike their French colleagues, Scandinavian artists do not seem to have been greatly preoccupied with depicting major medical inventions or to have any particular interest in portraying various medical advances.2 The doctor in the picture has no name, and indeed Ancher’s work is not a portrait of a specific doctor, but rather of the situation itself – a vaccination. The subject is unique in Ancher’s oeuvre: she painted no other works with medical themes, and this is also the first and only time that a medical figure appears in her art. In many ways, A Vaccination is a rarity, not only in terms of Ancher’s own works, but also in relation to other Scandinavian works from the period. While medical figures can certainly be found in Scandinavian art, only a few other artists from Denmark, Norway and Sweden appear to have tried their hand at a vaccination motif.3

But what happens if we stop focusing on Anna Ancher’s painting as an experiment with light and colour, instead considering it in a context which emphasises other depictions of health-promoting initiatives from the era? Taking its point of departure in Anna Ancher’s A Vaccination and a study of how the work was received in its own time, as well as of how it is perceived in the most recent research, this article takes a closer look at how advances in public health and in disease prevention were portrayed in Danish art at the end of nineteenth century. I will argue that with her vaccination picture, Anna Ancher inscribes herself in a field that is also preoccupied with depicting children as an essential part of the narrative of public health, reflecting how children, being representatives of the next generation, are extremely important to that narrative.

Recent decades have seen an increasing focus on Vitalism in Scandinavian art, giving rise to exhibitions and research-based publications, but less attention has been paid to how artists have portrayed initiatives to promote public health such as vaccinations, the dispensing of medicines and vitamins and the treatment of diseases.4 Vitalism was greatly preoccupied with the worship and cult of the healthy body, a trait that permeated the discussion of disease and health in the late 1800s. The linguist Sven Halse has described the widespread public health culture at this time as a so-called pragmatic Vitalism, meaning a Vitalism that revolves around practical ideals pertaining to interior design, clothing, child rearing, etc.5 Vitalism can thus also be seen as a revitalisation of not only the individual human being, but of all of society, manifesting in the period’s literature, art, sports, music, science and architecture, but also in the great focus on health and hygiene typical of the late nineteenth century.6 But can works that are not considered part of category of ‘artistic Vitalism’ – meaning works that, in the words of Halse, do not focus on the innermost essence of life or are preoccupied with the sun, light, water, youth, and nude tanned bodies, with strengthening the body through physical exercises or staying out in the fresh air and the healthy sunshine – be described as ‘pragmatic Vitalism’? Or is something else at stake here? Taking its point of departure in Anna Ancher’s A Vaccination and an analysis of the work’s reception history, this article takes a closer look at a selection of Danish works that centre on public health initiatives as their focal point, but which at first glance fall outside the current understanding of artistic Vitalism, investigating whether these works may be categorised as an artistic version of pragmatic Vitalism.

Exhibition history

Up until 2013, Anna Ancher’s A Vaccination was in private ownership, known only from descriptions in letters, various small-scale studies and a black-and-white photograph, the latter being included in publications such as the first major retrospective about the artist in 1994/1995.7 Even though A Vaccination was not part of the exhibition, it still received quite a lot of attention in the catalogue, where it is described as a cheerful image that not only demonstrates Ancher’s interest in medical advances and their positive impact, but also her care for the next generation.8 However, the author – German art historian Heide Grape-Albers – concludes that the subject has a direct kinship with the period’s depictions of people in waiting rooms, and that the cropping and colour scheme reveals that Ancher was inspired by Norwegian artist Christian Krohg (1852–1925).9 However, Grape-Albers does not place the work within the context of medical science, nor compare the work with other depictions of vaccinations, although this subject (and other depictions of working doctors) had its heyday in the 1880s and 1890s.10

The most recent and as-yet largest retrospective exhibition about the artist, Anna Ancher, created and presented at SMK, the Art Museums of Skagen and Lillehammer Kunstmuseum in 2020–21, Ancher’s A Vaccination is featured as part of the theme ‘Community’.11 The category also includes paintings of subjects such as Christmas geese being plucked, women braiding wreaths in anticipation of a royal visit, and paintings showing Anna Ancher’s mother, Ane Brøndum (1826–1916), with a little girl. Here the focus is on everyday communities, those that arose in the kitchen or in the field as well as on those ‘[…] showing the different generations together, and finally the communities found between friends’.12 According to this classification, the work is about communities, and perhaps it also ties in with the exhibition’s overall aim of showing Anna Ancher as a modern artist who looked towards French avant-garde painting for inspiration while upholding a special focus on light and colour. When presented in Skagen, the work was shown under the collective heading ‘Everyday Life’, and the overall text on the theme stated, among other things, that ‘Anna Ancher’s works are essentially depictions of everyday life and social life in Skagen; of people engaged in mundane chores, either alone or with others. Her scenes show how people lived, worked and made the day go by in a small fishing town, but at the same time they also depict a sense of fellowship and community’; the text also mentions that the painting shows a smallpox vaccination taking place.13 Once again, the picture’s references to medical science receives no mention.

While the painting is included in the catalogue, readers need to leaf through the entire book before finally finding a reproduction and mention of the work.14 This is because A Vaccination is not addressed in any of the articles in the catalogue; not until the biography is the painting mentioned alongside A Funeral and A Field Sermon as examples of the major figure compositions created by Ancher after her time in Paris in 1889.15 The intention of the exhibition was to pull Anna Ancher out of the context in which she is usually discussed, instead placing her among the leading artists of the time, or, as the catalogue puts it: ‘The ambition is to lift Anna Ancher out of Skagen, expanding the scope of our outlook from focusing only on the artists’ colony and Naturalism, positing her instead within the other, broader contexts her art so richly deserves’.16 The wider contexts in which the exhibition’s curators have wanted to place Anna Ancher’s art include French avant-garde movements such as Impressionism, while other sources of inspiration, including Naturalism and Dutch seventeenth-century art, are mentioned only sporadically.17 A single article in the catalogue argues that Anna Ancher’s preoccupation with light could be seen as a combination of Vitalism’s penchant for the subject, which includes illumination as a carrier of a distinctive spirituality, capable of animating and enlivening a space with its presence.18 The article is not about A Vaccination, and the fact that the work itself was placed on the periphery of the publication supports the thesis that in many ways it falls outside the scope of Ancher’s usual subjects and does not easily fit into the themes often discerned in her works; while she created several paintings with multiple figures depicting the religious life in Skagen, the vaccination lancet is only swung once in Ancher’s entire oeuvre.19

The inception of the work

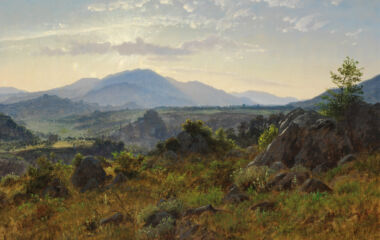

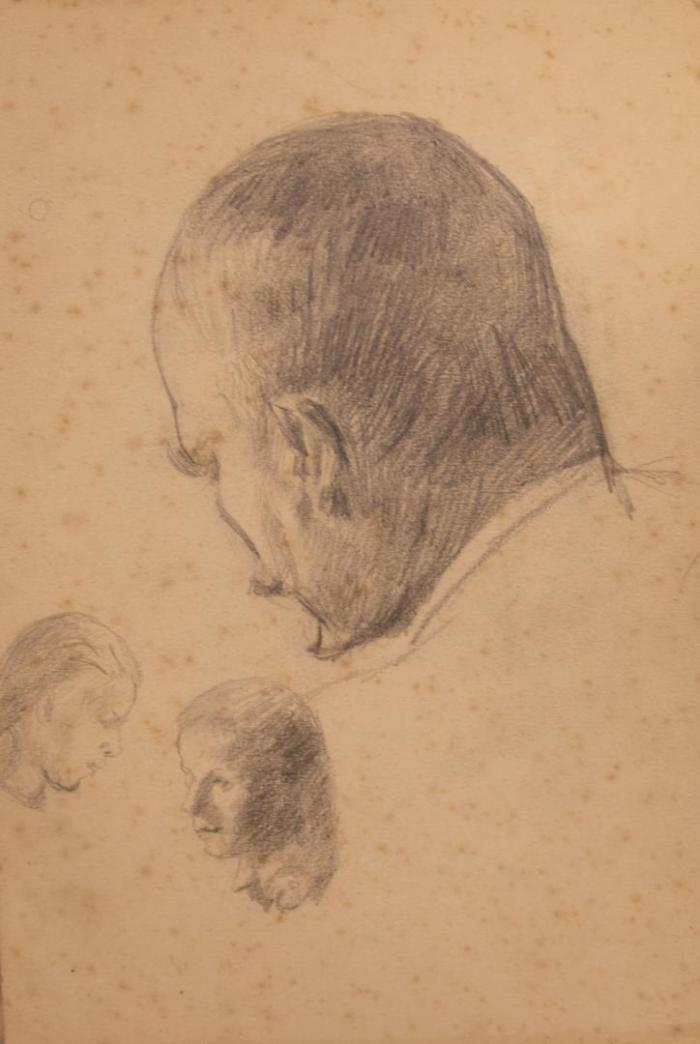

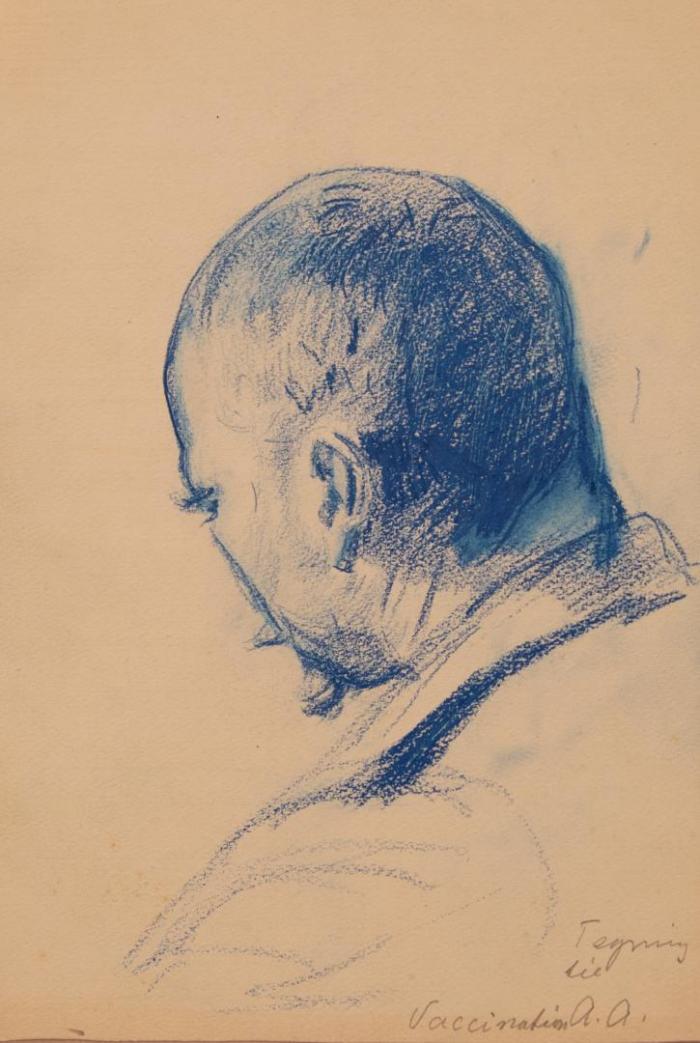

We do not know where Anna Ancher got the idea to paint a picture of a vaccination scene, a work which, in terms of size and the number of figures depicted, is surpassed only by her A Funeral and A Field Sermon. Aside from featuring many figures, all three share the trait of making no reference to a specific situation in the title, nor identifying exactly which event is being shown and where it takes place. In the vaccination picture, Anna Ancher has used her husband Michael Ancher (1849–1927) as a model for the doctor, seemingly indifferent to whether her model was in fact a representative of the medical profession [Fig. 2 and Fig. 3].

The composition of the picture was not given from the beginning: in what must be an early compositional sketch, Anna Ancher has sketched out a very different composition than the one seen in the finished work [Fig. 4].20 The sketch shows eight mothers, nine children, and to the left side of the picture is a doctor who, in the finished version, is vaccinating a child sitting on its mother’s lap. Judging from the doctor’s profile, Michael Ancher did not sit for the figure of the doctor in this sketch; instead, the person depicted may be the district physician in Skagen.21 In all likelihood, Anna Ancher did the sketch on-site while the vaccinations were taking place, but according to a letter from her mother, Ane Brøndum, Ancher was not entirely satisfied with the result, which may explain why she changed the composition in the subsequent sketches [Fig. 5].22

A comparison of the two compositional sketches reveals that the most significant change did not concern the number of people in the picture, but rather their placing inside the pictorial space. In the first sketch, the waiting mothers and children are arranged in a fairly uniform band across the picture plane, while the second sketch places all figures, including the doctor, on the right side of the image and introduces variation in the crowd by having some of the mothers stand up while others sit down. This variation is emphasised in two smaller oil sketches, one of which is completely true to the drawn version, except that the oil sketches also act as colour studies [Fig. 6 and Fig. 7]. Another significant change from the first to the second compositional sketch concerns the location of the windows. The first sketch shows only a very loosely sketched window, while the second has two and hints at a third. Windows play quite a significant role in Ancher’s overall oeuvre, often serving to bring in the (sun)light which was, even in Ancher’s own time, duly noticed as one of the most distinctive and important traits of her art. In this context, the windows not only bring light and sunshine into the room, they also have purely practical significance as the doctor needs daylight to be able to perform his work – in this case a vaccination. I shall return to this point later.

What the critics said: Exquisite colours, amusing, and cheerful

A study of the reviews and press mentions of the works Anna Ancher exhibited in the 1880s and 1890s shows that even at this stage, critics notice what they describe variously as her ‘sense of light and colour’, ‘bright, sunny atmosphere’ and her ‘gift for colour’. Such descriptions are a more or less recurring feature whenever her works are mentioned and/or reviewed by the critics of her own day.23 The emphasis on the reproduction of light and colour as well as on Ancher’s (natural) talent remains largely unchanged, and although she also received criticism, negative comments and reviews are in the minority compared to the positive reviews.24 This perception of Anna Ancher’s work is carried over into the general literature on the Skagen painters, but in this context it is more interesting to observe that the reviews are generally strikingly similar regardless of the subject matter of the works, highlighting that the perception of her works did not change much among critics in the late 1800s.25 Some of the works mentioned in the reviews from the 1880s and 1890s are: A Mother with her Child, Blind Woman, Old Couple Plucking Gulls, Sunshine in the Blind Woman’s Room, Evening Prayers, Sunlight in the Blue Room, A Funeral, The Fisherman in his Living Room and finally in 1899 A Vaccination.

A Vaccination was only exhibited once during Anna Ancher’s own day before being sold to the Swedish match manufacturer Lars Johan Frederik Löwenadler (1854–1915).26 The fact that the work was sold before it had even been exhibited was very unusual for Anna Ancher, so unusual that the fact was reported by the press, which cheerfully added that she had received DKK 7800 for the picture.27 But apart from a few newspapers’ focus on the sale of the work, the reviewers generally characterised the work as: exquisite in colour, amusing, enjoyable, superior and successful while describing the subject matter as a Skagen scene with a doctor vaccinating (screaming) local fishermen’s children.28 A single reviewer noted, with ghoulish glee, how ‘[…] blood is dripping from the soft little arms’,29 while the more wide-ranging societal aspects of the theme were also duly noted: ‘An amusing trait is the small group of children who have put these strange goings-on behind them, for the first time ever facing the demands of society and the common fate associated therewith’.30 With this observation, the reviewer is the only one to see anything other than a light-filled and cheerful tale about a doctor carrying out vaccinations. The reviewer points out the social aspect of the subject, regarding the vaccination as an expression of being aware of one’s social responsibility: being vaccinated is a good deed that benefits the community.

Apart from the two reviews mentioned here, the general critique of the vaccination picture does not differ significantly from other reviews of her other late nineteenth-century works. Presumably because Anna Ancher had by then already been categorised as an artist who was more concerned with colour and light than with her subjects. As one reviewer remarked about her works: ‘These are the same friendly interiors we know from previous years, and as ever a bright, sunny mood pervades them’.31 The critics of the time largely agreed that Ancher’s subject matter was subordinate to the colours and to the effect of light on the interior, and thus the approach to Ancher’s art to which the latest retrospective exhibition of Anna Ancher’s works also subscribes would appear to have been already established in her own time. The difference between then and now is that the Danish critics of the late nineteenth century were less aware of various contemporary French sources of inspiration such as the French Impressionists and Symbolists, who are highlighted as significant sources of inspiration for Ancher in the latest exhibition catalogue.32 The emphasis on colour and light as a distinctive quality of her works is, as has been proven, not a new aspect of her reception, even though the most recent research highlights her use of light and colour in describing her as a modern artist in line with the French Impressionists. Hence, it is hardly surprising that in the most recent retrospective exhibition, A Vaccination is placed in the category of scenes from everyday and community life, for how else might one understand a work that differs significantly from her other works in terms of subject matter, but which is also characterised by her use of light and colours?

Smallpox and art

Scenes featuring a doctor carrying out vaccinations are far from unique in a European perspective: the subject appears among English and French artists as far back as the early nineteenth century as the smallpox vaccine became more widespread among the people of Europe. Accordingly, the subject had been around for approximately 100 years when Ancher chose to paint it, and it was not a controversial theme. The medical profession of nineteenth-century Denmark was not opposed to the smallpox vaccine; only a few sceptical doctors can be found in the Danish debate about the vaccine, which focused mainly on whether it should be mandatory for all Danes or not.33

The smallpox vaccine became widespread in the late eighteenth century, when the English physician Edward Jenner (1749–1823) demonstrated that inoculation with cowpox pus directly into the blood offered extremely effective protection against being infected with smallpox, and it was he who immortalised the word ‘vaccination’ in 1798.34 The fact that Jenner infected people with pus from cows was the cause of much debate and all sorts of satirical cartoons, especially in English media. Visually, the scepticism is most clearly expressed in some of the satirical drawings of the time, such as those of English artist James Gillray (1756–1815), famed (and infamous) throughout Europe for his political and social visual satire [Fig. 8].

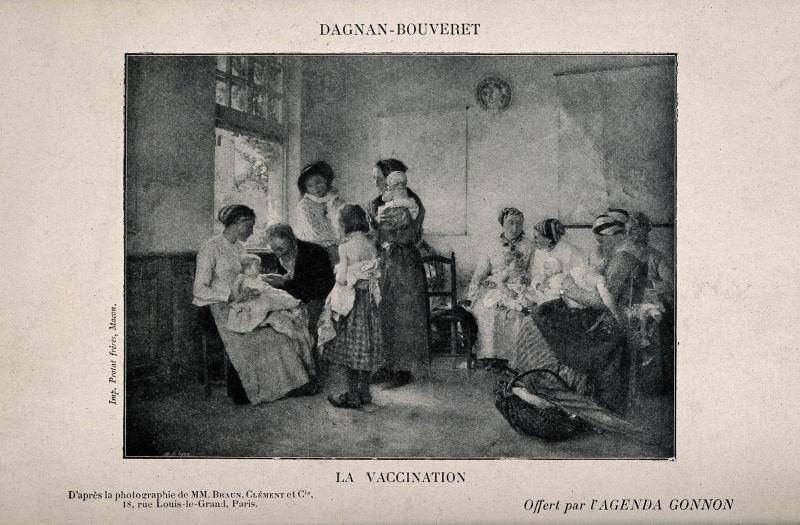

In Gillray’s drawing, Jenner is in the process of vaccinating a group of people, several of whom have, after receiving the vaccine, acquired extra limbs in the form of cow-like growths. However, Ancher’s work features no aspects of social satire, and the Danish satirical magazines of the time contain no illustrations that are critical of vaccines.35 In this respect, it would be more relevant to turn one’s attention to France, which she visited in 1885 and again in 1889. In the 1880s, several French artists painted pictures featuring named as well as anonymous doctors carrying out inoculations with various vaccines.36 They included Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929), who in 1882/83 painted The Vaccination of the Children [Fig. 9], a work which shares several compositional traits with Ancher’s scene [Fig. 10].37

Dagnan-Bouveret’s painting was exhibited in Paris in 1883, and while it was noticed by the reviewers, it elicited less enthusiasm than two other works of his previously exhibited there.38 It is likely that Anna Ancher also saw the work at the Exposition Universelle given that she spent six months in Paris in the spring of 1889 to study, work and view the exhibition.

The early nineteenth century saw the emergence of the first portrayals of smallpox vaccinations painted by French and English artists. A typical trait of the evolution of the theme is that the first works from around 1800 focus mainly on Edward Jenner and his initial experiments conducted on his own family.39 However, examples of more anonymous doctors are also seen, such as in the French artist Louis-Léopold Boilly’s (1761–1845) 1807 painting, which, like so many other works, was reproduced as a print, allowing the works and their depictions of vaccination to reach a wider audience [Fig. 11]. In this way, the artists’ depictions also served, directly or indirectly, as a subtle form of propaganda: they could help nurture the idea of the necessity to have one’s children vaccinated, especially in France where the smallpox vaccination only became mandatory in 1902.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Jenner’s figure was gradually replaced by anonymous doctors carrying out vaccinations. In these works, the focus no longer falls on the inventor of the pioneering medical invention, but on the act itself: on vaccinating and being vaccinated. The smallpox vaccine was one of the century’s greatest inventions in medical science, and until the chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–95) invented a vaccine against rabies in 1885, smallpox was the only vaccine offered in that century. Like so many other professions, the doctors of the period needed daylight to carry out their work, and accordingly one almost always sees the doctor carrying out the vaccinations near a window. This is also the case for Ancher’s doctor: here the light not only serves an artistic function, demonstrating the artist’s skill at depicting dappled light and sunshine falling in through the window onto the floor or wall – it also serves a practical function. Thus, windows or open doors are staples of the iconography of vaccination scenes.

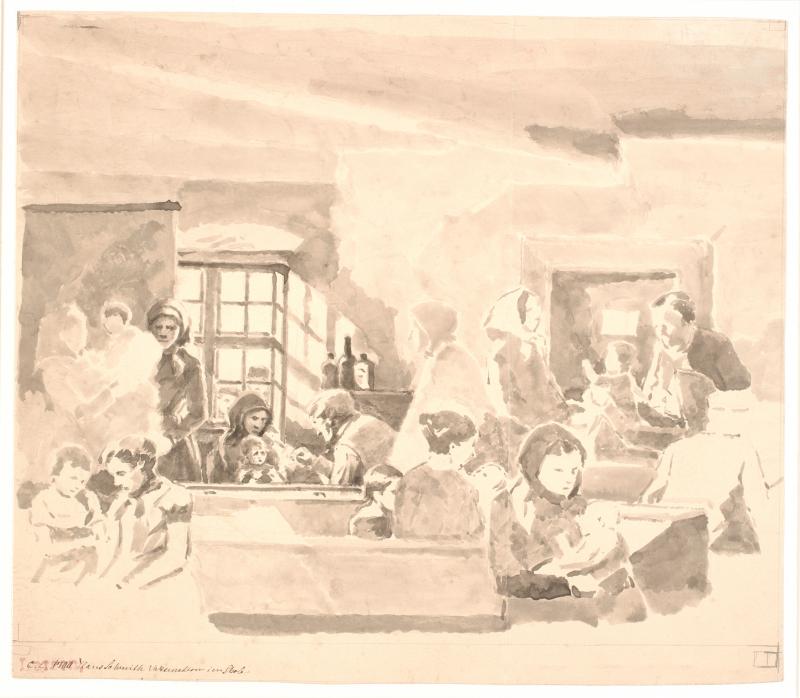

In Denmark, the vaccine was declared mandatory by law in 1810, and the few known Danish artistic depictions of doctors carrying out vaccinations have several similarities with the English and French versions of the subject, where an unnamed person, typically either a doctor or a clergyman, is carrying out the vaccinations while several people are gathered for the event.40 One example is Danish painter Hans Smidth’s (1839–1917) drawing Vaccination in a School, where the doctor is about to cut the child’s arm with his lancet [Fig. 12]. Here too, the mother is shown sitting with her back to the window so that the light falls onto the little girl being vaccinated, while two children stand outside the window looking in at the proceedings. Vaccination scenes with plenty of figures first appeared around 1800, meaning that Anna Ancher does not add anything new to the theme in terms of its composition. However, instead of the cool daylight found in most vaccination scenes, Ancher has created a scene awash with the bright, glowing sunlight for which she became particularly known in the 1880s and especially in the 1890s. The uncontroversial nature of the subject at the time, coupled with the fact that Ancher flooded the scene in the light for which she was so well known, may be part of the explanation why the painting was not particularly noticed in its own day, even though it is in fact a rather unusual subject in a Danish and Nordic context.

Prevention, treatment and cure

Vaccinations were not the only public health measure depicted by nineteenth-century artists. In France, for example, institutions were built to promote hygiene among mothers: the authorities wished to reduce child mortality and encourage French families to have more children. In the promotions made by the French Republic, artists also played a role, being commissioned to paint depictions of some of the Republic’s public health initiatives. One example is the French artist Henri-Jean-Jules Geoffroy (1853–1924), who in the late 1800s was involved in several of the French state’s new hygiene and sanitation measures, helping to educate the French people on such matters.41 In Denmark, the state authorities showed less interest in using art as propaganda to promote a particular cause, so it is no wonder that it is much more difficult to find Danish and Nordic art focusing on these topics. However, a few examples of such works by Danish artists do exist, their themes sharing a certain kinship with Geoffroy’s depictions of French institutions, focusing on children’s health and hygiene.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, artist Valdemar Irminger (1850–1938) painted several works from Kysthospitalet (the Coastal Hospital) in Refsnæs, an institution originally set up in 1875 for the benefit of children with tuberculosis. The hospital’s main medial officer Vilhelm Schepelern (1844–1924) and its inspector Niels Christian Ottesen (1841–1902) were both interested in art, and several artists took up residence as Schepelern’s guests. Their numbers included the painters Harald Foss (1843–1922), Irminger and Laurits Tuxen (1853–1927).42 Irminger’s works, which comprise large and small formats alike, focus particularly on the sick children, and just as in Anna Ancher’s vaccination scene both sexes are seen, even though the girls are in the majority in both artists’ works [Fig. 13]. While hydrotherapy conducted in specially designed bathrooms was one of the Kysthospitalet’s foremost remedies, Irminger frequently chose to instead portray the sick children out in the fresh air, often on the beach near the sea.43 If judged solely by their faces, the children in Irminger’s works do not look particularly sick; instead, the crutches and stretchers found in the majority of his pictures serve as markers of their disease. In the painting of the letter-writing girls, who certainly do not look sick, we also find a crutch in the background [Fig. 14].44 Irminger’s first painting from the Kysthospitalet was exhibited at the juried spring exhibition at Charlottenborg in 1888, and later that year he received the academy’s annual medal for the work, demonstrating that his work received the official stamp of approval for this particular subject.

Tuberculosis was a major public concern at the time, with one-third of all deaths between the ages of 15 to 60 being caused by the disease.45 The importance of fighting tuberculosis was also communicated in the newspapers and magazines of the day, helping to boost support for initiatives such as the establishment of the Kysthospitalet and of sanatoriums.46 Constructed with financial aid from private foundations, state grants, various municipalities and institutions as well as private donations, the Kysthospitalet became so popular that in 1880 it had to reject patients because there was no room. The hospital was expanded several times during the 1890s, creating better facilities for patients and staff.47

Irminger’s works, several of which were exhibited at the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition, would also have served to promote the place, its surroundings and not least its healing and beneficial societal impact, especially because Irminger’s series of works from the Kysthospitalet also includes a picture of discharged patients driving away in a horse-drawn carriage [Fig. 15].48 The patients have been healed thanks to their stay, enabling them to leave the Kysthospitalet behind – without any crutches. The works can be seen as a series that collectively describes life at the Kysthospitalet and the treatment given to the children admitted there. Outside of these works, Irminger’s favourite subject matter was family scenes and landscapes, and he did no other depictions of sick children except for those from the Kysthospitalet. It would appear that his depictions of consumptive children are the only examples in Danish art of an artist portraying the work done at sanatoriums to cure sick children.

The treatment of already ill children was not alone in being reproduced in the visual arts; preventive measures were also committed to canvas. In 1886 Emilie Mundt (1842–1922) exhibited the painting From the Orphanage in Istedgade [Fig. 16] at Charlottenborg, and five years later the asylum on Blegdamsvej was the subject of a painting by Knud Erik Larsen (1865–1922). At first glance, these works are not very obviously about measures to promote public health, but indirectly they tell the story of how private initiatives for the benefit of working-class children and their working parents did not just build on an idea of taking the children off the streets and the dangers lurking there, but also extended to taking care of the children’s health.

Mundt’s painting contains all the things that a children’s asylum offered the children being cared for there while their parents were at work: general education, cleanliness, crafts, tending to wounds and physical injuries, nourishing food and lessons. Like the Kysthospitalet in Refsnæs, the children’s asylums were funded by charity and private donations; they had their own boards and were not subject to state control. Several of them were later converted into kindergartens, but their original purpose was to take care of the physical and spiritual upbringing of children so that their parents could carry out their work outside the home. They also strove to keep children who were left to their own devices during the day away from the streets and from so-called bad influences. The asylums not only looked after the children, but also gave them a meal, milk and vitamins, in addition to which ‘the children are washed a couple of times a day […] Those who need it are treated with disinfectants, ointments, cod liver oil, dressings etc.’49 All these initiatives aimed at improving their health and making the future generations healthy and strong.

While most reviewers praised Anna Ancher’s vaccination picture for her work with light and shadow, Mundt’s critics were not impressed by her use of colours or light. In fact, one reviewer even described that her technical skill with colour failed to impress, but added that ‘[…] there is much in this painting that is pretty and healthy, it is greatly to the artist’s credit that she has eschewed the sympathy so easily won among superficial spectators presenting a quantity of “little dears”’. The same writer notes how one can tell the children’s breeding or descent by their relative strength or weakness.50 The reviewer does not elaborate on exactly how this health manifests itself, but the observation may be an acknowledgment of how Mundt chooses to portray how the children are kept clean, taught to sit still, knit, sew and draw or solve tasks. Mundt is also praised for not painting a sentimental picture of darling little children; with this, the reviewer points to the fact that her picture does not try to pander to the viewer’s emotions, preferring instead to present a more realistic picture of life in the asylum. Mundt’s work is a visual testament to the general efforts to promote education, cleanliness and health, sentiments on which these asylums were built.

Another example of a depiction from a children’s asylum is Larsen’s From the Children’s Asylum on Blegdamsvej. Dispensing Cod Liver Oil to the Children [Fig. 17], exhibited at the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition five years after Mundt’s version.51 In the slightly dark foreground, a group of young boys and girls are waiting for – or have received – their cod liver oil from one of the asylum assistants. In the background is another group of children near a window from which golden sunlight flows. In the foreground to the left, a pale boy looks out at the viewer, presumably to arouse our sympathy and to beckon us into the picture; his sad face and the grey-toned foreground constitute a stark contrast to the luminous, more colourful background. Even though the window in the background lets in the light, and the viewer’s gaze is drawn in by the almost luminous diagonal formed by the bare floor between the children, the true subject of the picture is the group of ‘grey’, pale children in the foreground. Perhaps the light in the background is intended to quite literally remind the viewer that there are brighter times ahead or that children ought by rights to be outside enjoying the excellent weather, but the work also indirectly points to the prevalent interest in health, cleanliness and hygiene in the late nineteenth century. In that narrative, the sun, light, air and not least children and young people played crucial roles: they represented the new generation, making it essential to keep them healthy and well. Such concern for children’s health – and lack thereof – was widespread in the late nineteenth century, which saw the publication of several books focusing on the subject. What is more, several doctors believed that the children of the late nineteenth century were weaker and more prone to sickness than previous generations, a situation ascribed variously to hereditary conditions, an unhealthy diet, too much coffee, and lack of exercise, resulting in a weak physique.52

In 1892, Larsen’s painting was reproduced in one of the most popular magazines of the era, Illustreret Tidende, meaning that it reached a wider audience just like several of Irminger’s paintings from the Kysthospitalet. One of Irminger’s scenes from the Kysthospitalet accompanied Larsen’s work, prompting one reviewer to describe Irminger’s and Larsen’s works as ‘scenes of Hospital atmospheres’.53 Another reviewer had obviously tired of works on these subjects, describing the recent tendency to portray disease in art as ‘[…] the epidemic propensity to make illness the subject of artistic representation,’ and he was none too keen on Larsen’s work and ‘[…] the scrofulous nature of this throng of highly different toddlers’.54 Here the reviewer is presumably also referring to the fact that since 1870, the Charlottenborg exhibitions had indeed seen several works that revolved around illness, convalescence and hospital rooms.55 Apart from this, Larsen’s work was praised for its sympathetic portrayal of the children and for its rendition of fresh, clear light.56 While Larsen’s picture focuses on the distribution of cod liver oil, it too – like Mundt’s picture – features a child with a bandaged head, serving to emphasise the health measures that were such an essential part of the children’s asylums’ work, ensuring that any scrapes and wounds were attended to and their health promoted. Among their many activities, which included keeping children off streets and teaching them manners as well as lessons, the institutions were also dedicated to keeping the children and giving them access to fresh air and movement.57 Mundt’s and Larsen’s pictures of more or less grey, pale children not only offer a glimpse of what life was like at a children’s asylum; they also contribute directly to the period’s discussion of the importance of future generations’ health symbolised by the younger generations – the children and the young. Or as one doctor put it:

It is finally a truth universally recognised by all who have dealt with the conditions of the population, that the mortality and morbidity of the youngest children is the most faithful reflection of the position held by a nation with regard to civilisation, material well-being, and their appreciation of the demands of health care.58

Pragmatic Vitalism

As has been demonstrated above, some of the period’s ideas about health, both in terms of prevention and treatment, were also depicted in the arts. The works by Ancher, Mundt and Larsen all show some of the steps taken to promote public health in the nineteenth century, and Irminger’s painting from the Kysthospitalet in Refsnæs showcases the era’s treatment methods for children and young people afflicted by tuberculosis. But can they – and especially Anna Ancher’s work – be included in the concept of pragmatic Vitalism? Seeking to more closely identify what can be characterised as Vitalism, Sven Halse divides the concept into three spheres: natural philosophy Vitalism, artistic Vitalism and pragmatic Vitalism. The kind of Vitalism associated with natural philosophy has its origins in the idea that living nature possesses a special life force, while artistic vitalism ‘[…] addresses what the Vitalist tradition understands as “the innermost essence of life” […]’59 Halse also argues that it does not make sense to describe an artistic or pragmatic cultural phenomenon as Vitalist unless it is also in keeping and harmony with the natural philosophical sphere.60

Tested up against this definition, the works analysed here do not fit in – and even less so when the central themes of artistic Vitalism are described as focusing on light, the sun, the sea, the naked body and tanned skin. However, Halse himself opens up an opportunity for the works to fit into the pragmatic Vitalism described as the Vitalist health mindset. A mindset which found expression in the period’s preoccupation with diet, architecture, hygiene, interior design, child rearing and more. Halse also describes how the cultural manifestations of pragmatic Vitalism are thematised in artistic Vitalism, for example in the form of works depicting bathing and sports. Pragmatic Vitalism is thus addressed in artistic Vitalism, but according to Halse’s definition, this does not include works that depict the general perception of health, preventive and curative measures such as vaccinations or the treatments of tuberculous children.

However, I believe that the concept of pragmatic Vitalism should indeed include works of art that address those efforts to promote public health which aimed to strengthen the physiques of future generations. Not necessarily through free play in nature or gymnastic exercises, but through vaccinations or otherwise caring for children’s health – the healthy child being a key part of the period’s thinking. Moreover, sunlight and fresh air were not only used to fortify children’s bodies; both elements also served a healing function for bodies afflicted by disease.

Irminger’s children and young people at the Kysthospitalet are ill, but the sun, light and fresh air in close proximity to the water help cure and alleviate their illness. While the children themselves may not appear healthy and strong, the idea of nature as the great healer has a strong kinship with the Vitalist mindset. I believe that when Anna Ancher floods her vaccination scene in sunlight, she not only does so only because she was preoccupied with light throughout her career, but also because light, in addition to serving a practical function as a source of light assisting the doctor’s work, acts as a health-giving, restorative light surrounding the children being vaccinated.

In all the works analysed here, health is promoted through diet, hygiene, medicine or the right upbringing, both intellectually and physically, but the paintings still constitute expressions of the idea of keeping the body healthy and well. Accordingly, art belonging to the category of pragmatic Vitalism can also include works that depict the period’s focus on health, prevention and hygienic measures, especially in relation to future generations, a point which attracted particular attention in the late nineteenth century. Children and young people thus not only served to showcase the healthy, naked and often also tanned body; they embodied hope for future, and so played a crucial role in the overall nineteenth-century focus on health.