Summary

The article examines and discusses the reasons behind Storm P.’s membership of the German society known as Die Nordische Gesellsschaft in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors take their starting point in Storm P.’s aspirations for an international career, analyse his financial circumstances from the late 1920s to the 1940s, and provide an account of how various steps were taken to promote Storm P. in Germany during this period. His political standpoint is discussed – including his views on religious and ethnic minorities.

Articles

Background

Different ages ask different questions. Back in 1977, when the Storm P. Museum first opened its doors, it was clear to all that Denmark ought to have a museum to celebrate the nation’s beloved humourist, Storm P. (1882–1949). He was a national treasure. Perhaps the closest you could get to the very incarnation of Danish humour and warm wit.1 But in 2008 the weekly newspaper Weekendavisen asked this polemical question: ‘Was Storm P. a Nazi?’

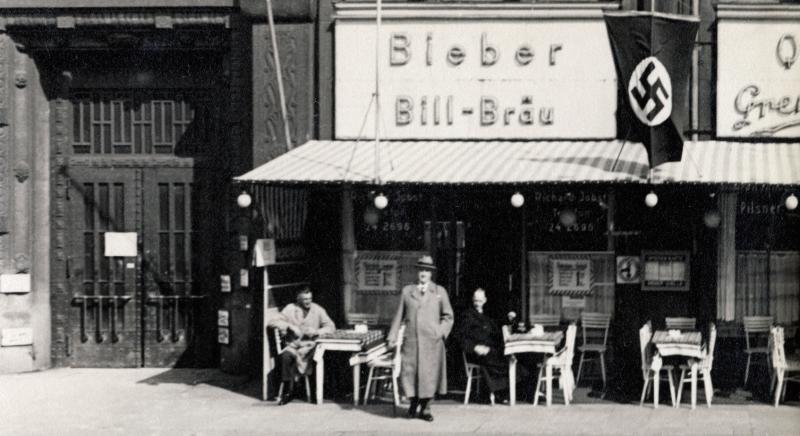

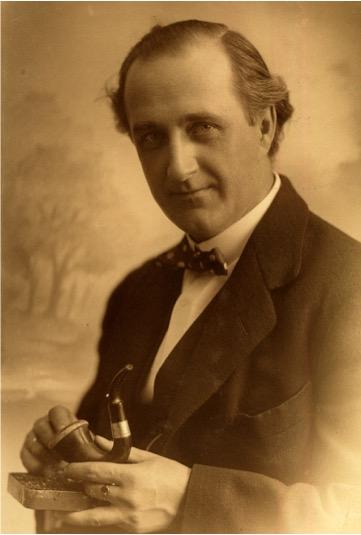

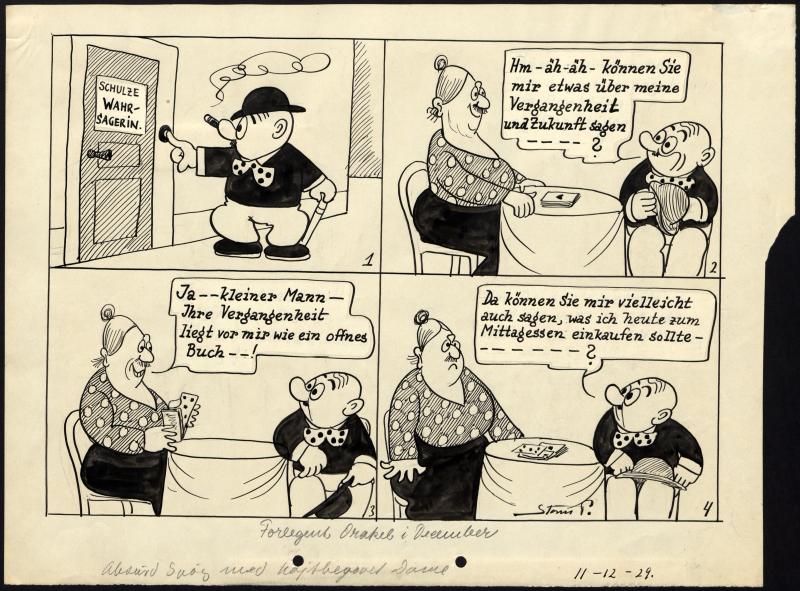

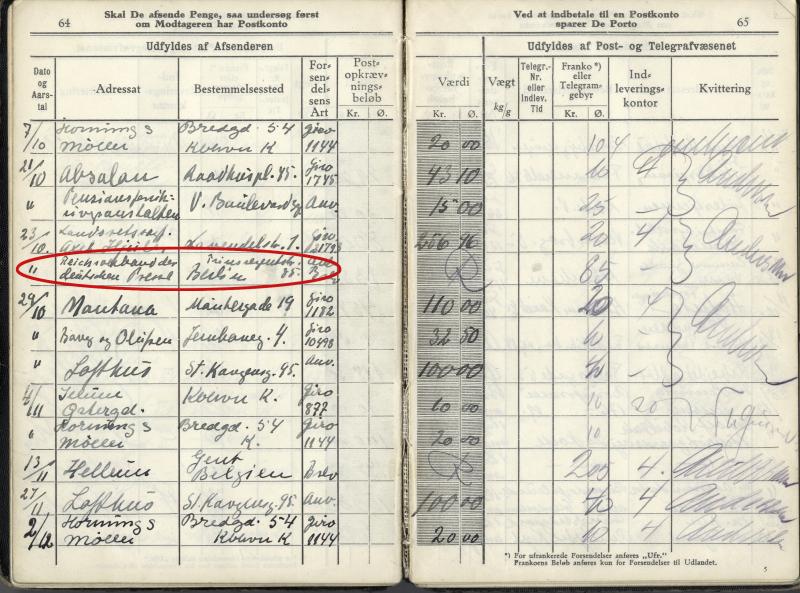

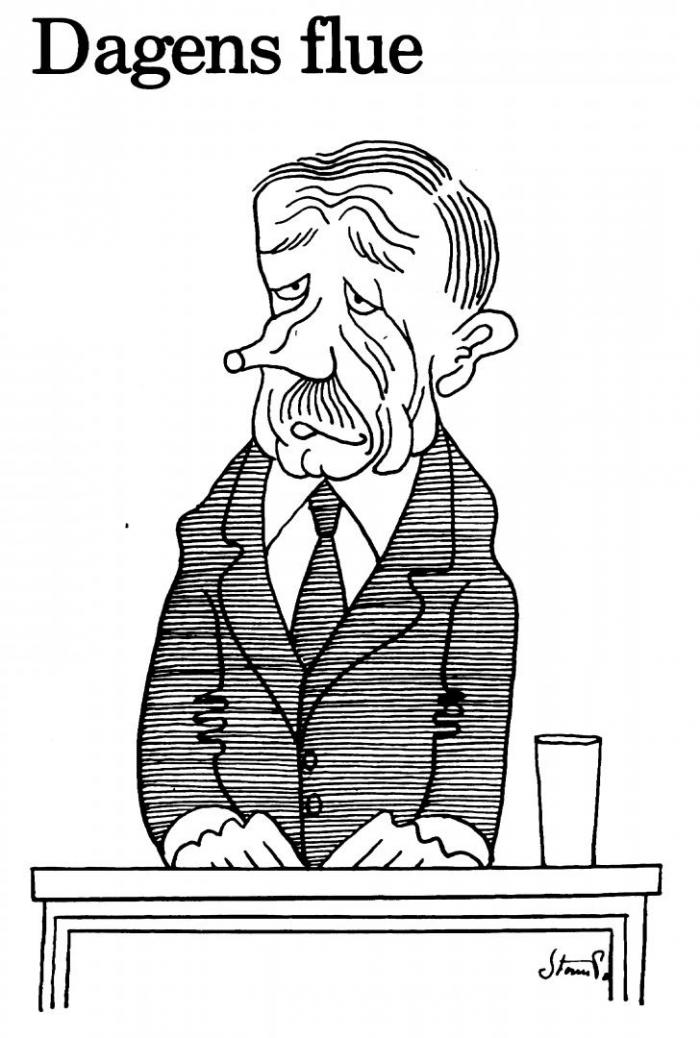

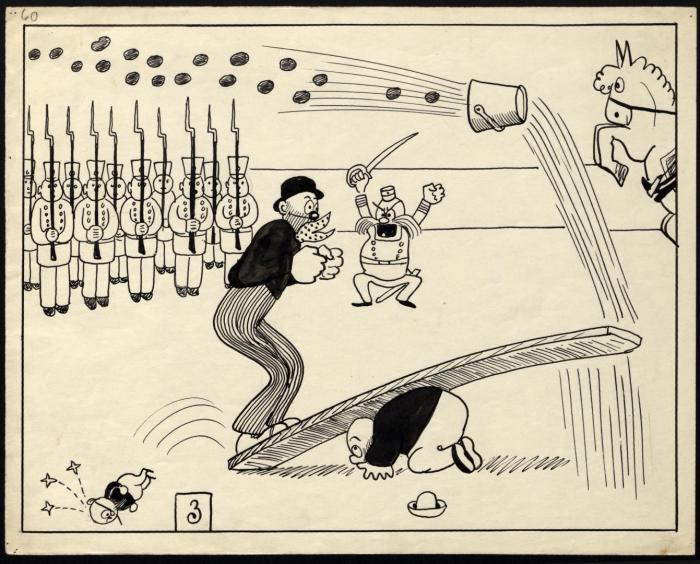

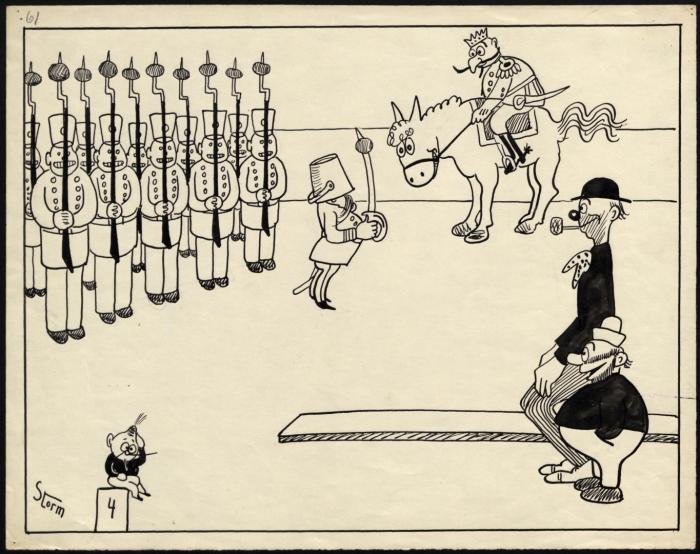

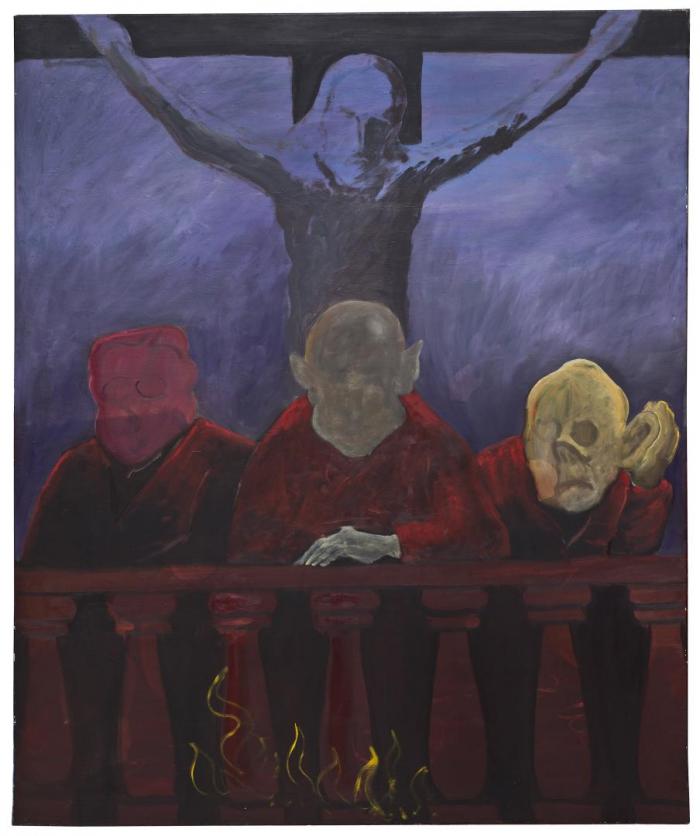

The question was prompted by an MA research degree thesis written by the music historian Lasse Olufson,2 which stated that in 1937 Storm P. became a member of the Nordische Gesellschaft, a German society that had been under Nazi control since 1933. At that point Storm P. was fifty-five years of age. He had been associated with the society since the late 1920s, primarily through his participation in an exhibition about Scandinavian caricature. However, the information about his membership was not new. The Danish newspaper Information had reported this fact back in 1945, shortly after the end of the war. We shall return to this point later. The Weekendavisen feature stirred quite a controversy in the press, prompting more or less speculative declarations about Storm P.’s mindset to be put forward. There was a general tendency towards being quick to read Storm P.’s membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft, and the fact that he paid a larger membership fee than most other members, as a sign of sympathy with the Nazi movement – a glaring contrast to the established picture of this much-loved artist. After all, Storm P. had always been considered an apolitical, humanist artist and humourist.3 The fact that the literature on Storm P. had never made any mention of this membership, which seemed to have been swept under the rug and forgotten since the war, only served to heighten the media’s sense that they were on the track of a sensation. [fig. 1 og 2]

Whatever the case may be, all agreed that this aspect of Storm P.’s endeavours merited further elucidation. And of course the question for which Lasse Olufson was quoted in several media – whether it is possible ‘to cooperate with and contribute money to a strongly Nazi organisation for years and still be considered apolitical?’ – is relevant in this context. The media controversy and the sensationalist headlines also illustrate a tendency towards a somewhat black-and-white outlook on the period leading up to and during World War II. One of the results of the media attention is that here at the Storm P. Museum we now often find ourselves responding to audiences who ask whether ‘Storm P. flirted with Nazism?’. The objective of the present article is to add greater nuance to the topic and to discuss the reasons why Storm P. joined the Nordische Gesellschaft shortly before the breakout of World War II. The research project continues in the vein of recent research on popular culture during the interwar years and during the German occupation of Denmark – with a particular focus on literature, film and stage.4 This article presents an account of Storm P.’s career with a particular focus on his wish to gain exposure in Germany and abroad in general. Finally, it also discusses his link to the Nordische Gesellschaft.

Jack of all trades

Storm P. was professionally affiliated with newspapers and magazines throughout his career. He had a modest debut as a caricature cartoonist at the age of twenty in 1902, and during the first decade of the century his work would appear in most of the Danish humorous publications in existence – of which there were many. After 1905 his occupations included those of a fine-art painter and an actor in films and on the stage, and from 1913 he was also an improvising stage artist – an “artiste”, as he himself called it – in intimate artist cabarets modelled on French examples.5 He had his first solo show as a painter and draughtsman in 1909.6 He was also a writer, publishing his first book in 1915.

From 1922 up until his death in 1949 he was permanently employed as a cartoonist and writer at the prominent Danish newspaper Berlingske Tidende.7 There can be no doubt that Storm P. himself regarded much of his cartoon work and other activities as work: as commissions and entertainments that gave him a livelihood while his artistic heart’s blood was poured into other aspects of his art, specifically drawing and painting.

Looking abroad. The first travels

‘[…] indeed yes, I have often thought that my work might possibly amuse people beyond the borders of my native country – it’s not beyond the realm of reason.’8

Storm P. began to look abroad at an early stage. He first did so in his mind’s eye by virtue of his fascination with literature, crime fiction, journalism, humour and art, all of which sent him on inner journeys across the world. Then came his first real trip abroad when he set out to sea in 1901, joining the crew of his uncle’s schooner to Bergen and Newcastle. He returned home from this journey carrying 95 densely filled pages full of records of his travels, drawings and ideas. These included copies of advertising signs and other forms of promotional materials in the American style. From boyhood and well into adulthood, Storm P. regarded America as the Promised Land where everything was possible.9

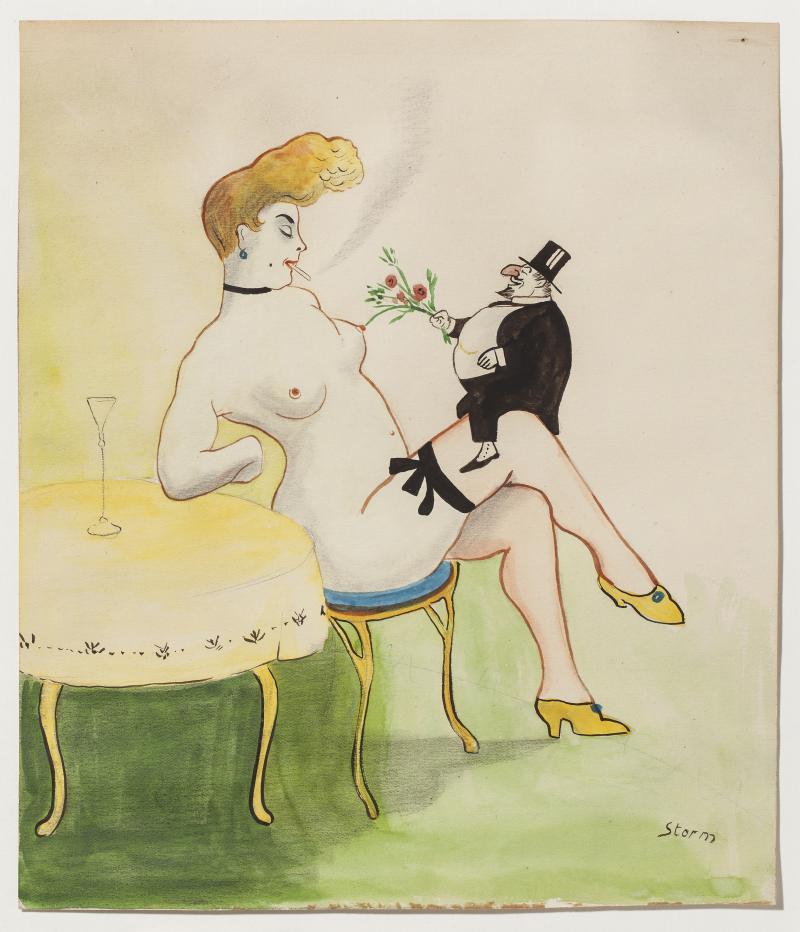

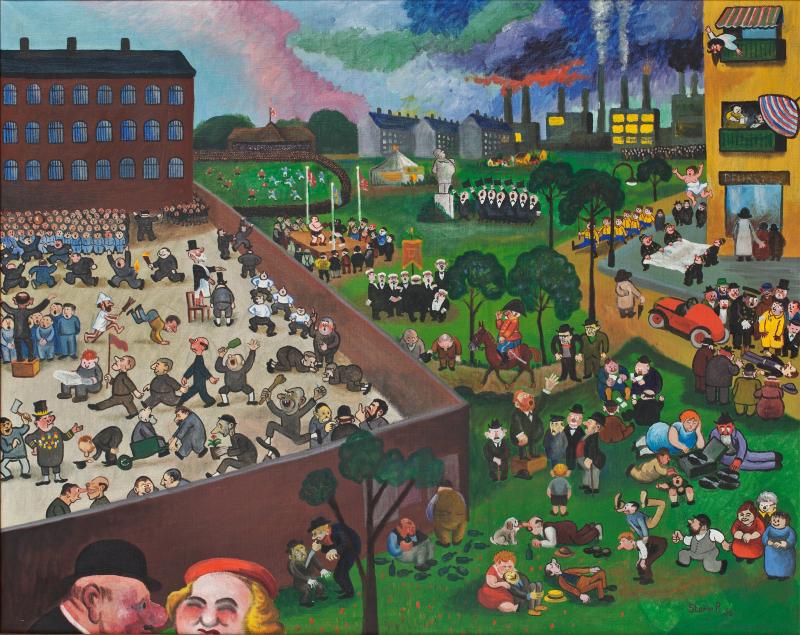

His second and seminal encounter with the world outside of Denmark came with his journey to Paris in the summer of 1906 – a trip made possible for the twenty-three-year-old Robert Storm Petersen by an acting grant. This trip reaffirmed his ambitions to realise a career as an independent, free artist, modelling himself on international examples. The cabaret acts of Montmartre, the bohemian lifestyles associated with that area, the large circuses and, crucially, the painting styles seen in Paris all made an indelible impression on him; one to which he would keep returning in his notes and snatches of recollection throughout his life. A few years prior to setting out for Paris he had already become strongly fascinated with Symbolism (such as the work of draughtsmen Johannes Holbek and Jens Lund) and especially with the painting of Edvard Munch. [fig.3]

His travel activities grew markedly in scope after 1913, the year in which everything that the 31-year-old Storm P. touched became gold. He created the series about De 3 små Mænd og Nummermanden (The Three Little Men and the Number Man), had his debut as an improvisational cabaret act and speed-drawing artist in the cabaret Edderkoppen (The Spider) and published his first Storm Petersen Album. All to resounding success. He toured not only Denmark, but also Sweden and Norway. In 1914 an engagement in Berlin alongside fellow artist Valdemar Willumsen (1879–1965) was intended as a springboard for an international career. The pair of them wanted to go further afield, specifically to the USA. However, World War I interfered with these plans, causing their trip to the USA to be postponed until 1919.10

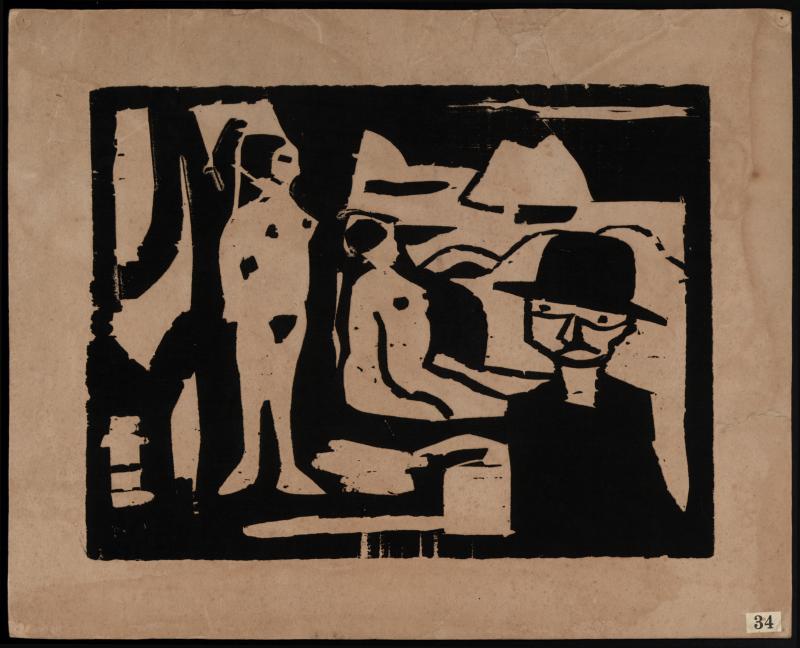

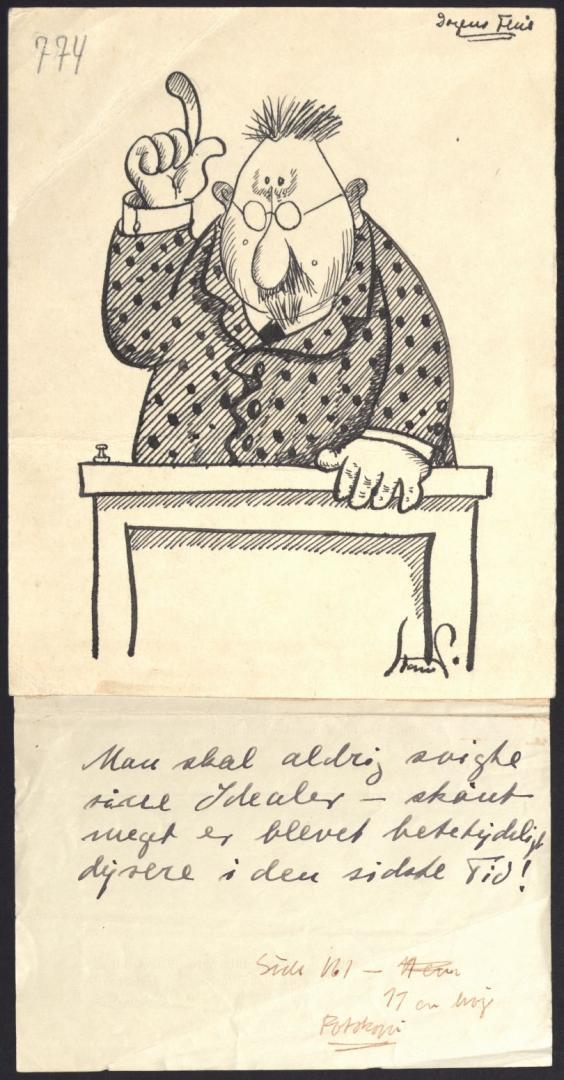

Storm P. and the German-European avant-garde

Storm P.’s links to Germany did not become firmly established until 1912, when he was contacted by the editor of the German Expressionist art journal Der Sturm, Herwarth Walden (1878–1941). Walden was one of the leading figures of the artistic avant-garde in the early 1900s. From his base in Berlin he acted as a conduit between artist groups, artists and exhibition venues throughout Europe. The Sturm artists, who also exhibited their work at the journal’s gallery in Berlin, included prominent figures such as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Oscar Kokoschka. Walden asked Storm P. to contribute to the journal, and the Danish artist responded by supplying two woodcuts.11 At that point Storm P. had already, in 1909, unsuccessfully sought to have his drawings published in the highly acclaimed German journal Simplicissimus,12 and he undoubtedly saw Der Sturm as a similar opportunity for raising his profile in Germany. In the autumn of 1917, Storm P. helped organise an exhibition of Der Sturm artists in the lobby of the artist cabaret Edderkoppen in Copenhagen.13 He exhibited his work twice at Walden’s gallery in Berlin in 1923.14 All this means that in several different ways, Storm P. acted as a conduit for the dissemination and exchange of modern art between Denmark and Germany. Storm P. remained in touch with Walden far up into the 1920s.15 [fig.4]

The 1920s proved anything other than a decade of painting for Storm P. His adventures in the USA left him in dire financial straits, prompting him to draw on his entire, and extensive, network in order to secure a stable income. This finally arrived with his tenure at the major Danish newspaper Berlingske Tidende in 1922, for which he created the series Peter Vimmelskafts oplevelser (Peter Vimmelskaft’s Adventures, also known as Peter & Ping), which also marked a significant turning point in his career, putting him firmly on the path of a career as a humorous cartoonist, writer and revue artist, moving away from satire and painting.16

Fig. 4. Storm P.: A Man and Two Women. Woodcut. Published in Der Sturm in 1913.

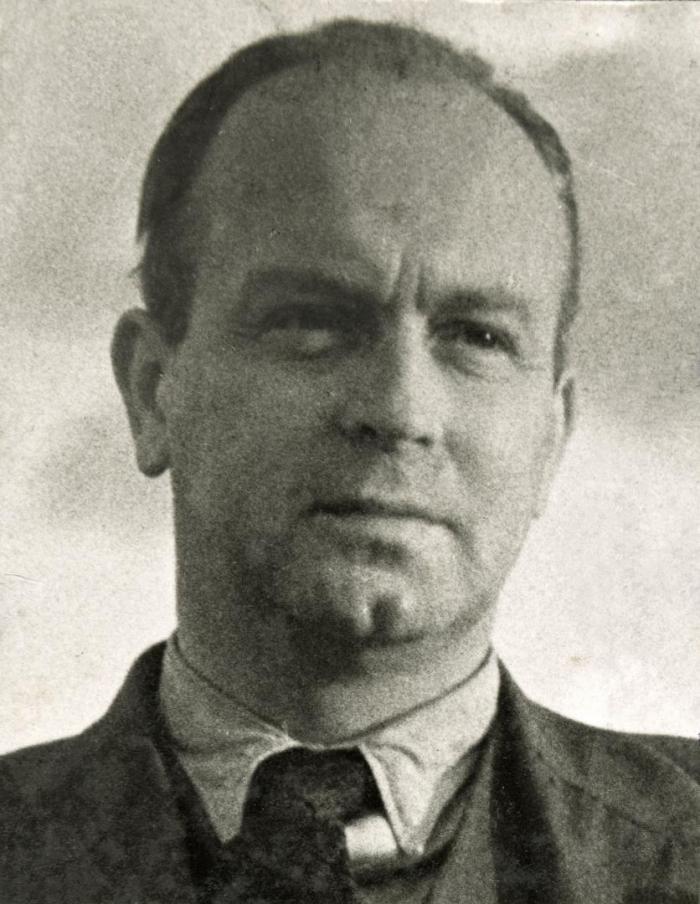

Adolf Kobitzsch

In the spring of 1929 Storm P. was contacted by a younger, German-speaking Romanian man called Adolf Kobitzsch (1901–45), who had recently settled in Denmark. Kobitzsch was very enthusiastic about Storm P.’s work, offering to use his connections within the European magazine scene to market him in Germany. Storm P. accepted this offer, and within a short period of time their endeavours succeeded in effecting substantial sales of drawings and stories for a range of German publications, including the nation’s leading comedy magazine Lustige Blätter, which was published weekly in print runs of no less than three million copies.17 The pair succeed in selling German translations of eight of Storm P.’s humorous tales to the leading journal Simplicissimus; these were published in 1929, 1930, 1931 and 1941.18 [fig. 5]

As was touched upon in the above, Storm P. had tried, to limited success, to sell satirical cartoons to leading German journals in the past, but at this point Lustige Blätter offered him a contract, and in 1933 the chief editor of the journal, Käthe Mehlitz, travelled to Denmark in order to get personally acquainted with the Danish humourist. On that occasion Mehlitz told Berlingske Tidende that she regarded Storm P. as ‘one of the greatest humourists that has ever lived’.19 [figs. 6 and 7]

Approximately a year after he first met with Kobitzsch, Storm P. was asked to take part in an exhibition about Scandinavian caricatures held in Lübeck, arranged by the Nordische Gesellschaft. At the opening the society’s business manager, Ernst Timm, gave a speech of which Kobitzsch gave this account in a letter to Storm P.:

[…] He mentioned that in recent years you have also conquered Germany – one only has to read Lustige Blätter, which has often filled entire pages with your drawings. He concluded by stating that you will undoubtedly find your place among the humourists of Germany, for with your ideas, which must rank among some of the most amusing caprices that the human imagination is capable of inventing, you represent a hitherto unknown vein of humour that makes you an artist of international significance. […]20

Storm P. and the German press association

After the Nazis had seized power in Germany in 1933, it grew increasingly difficult to maintain the momentum – career-wise and financially – that Storm P. had achieved south of the border in just a few years. Even something as simple as receiving money from Germany turned out to be virtually impossible. And in April of 1934 Fräulein Mehlitz announced that Lustige Blätter would no longer be allowed to publish Storm P.’s work unless he became a member of the German press association. Shortly before this time, the German media had all been brought under the auspices of Goebbels’s propaganda ministry, which wished to maintain control of everything that was published.

Dear Mr Kobitzsch!

I gratefully acknowledge receipt of your latest communication. I can use ten of the drawings, but the matter has been complicated somewhat because foreigners are now also required to join the Reich Association of the German Press. This is to say that I am only allowed to employ cartoonists who are members of this association. To this we may add the difficulties in conducting bank transactions; from 1 May onwards it will only be possible to transfer 50 Mark abroad at a time, and this includes giro transfers. All I can do is to distribute the payments over longer periods of time. For these reasons I ask you to discuss with Mr Storm Petersen whether he would want to become a member of our Reich Committee of Press Cartoonists, in which case I would be able to continue to work with him, and I do not think that he would have any trouble. The address is: Reichsausschuss der Pressezeichner im Reichsverband des Deutschen Presse, Berlin-Friedenau, Offenbacherstr. 5.21

With assistance from Kobitzsch, Storm P. acquired the necessary forms from Berlin, but soon discovered that the association demanded detailed documentation proving his own Aryan descent and that of his wife, Ellen, in the form of police-verified copies of the birth certificates of their parents and grandparents – as well as information about the religious and political allegiances of all their relatives. [fig. 8] Having collected this information, Storm P. returned the form to Berlin by registered mail on 23 October 1935. However, even though the papers would appear to have been correctly filled in, it seems that the official verifications from the police were not included: the German press association sent several reminders asking for these documents. Storm P. took no further steps in this matter and would appear to have abandoned his application for membership of the German press association. Some time later, the following notice was run in the Danish newspaper Dagens Nyheder:

Storm Petersen as National German Humourist?

In Berlin, Robert Storm-Petersen has requested membership of the editors’ association founded by Dr Goebbels. If this request is met, the famous Danish artist will essentially occupy an official position as a civil servant in Germany, as do all German journalists and editors under the National Socialist regime. Storm-Petersen’s art is greatly appreciated in Germany, and presumably membership of the Reichsverband der deutschen Presse is a prerequisite for the Danish humourist’s continued access to German magazines.22

We do not know where Dagens Nyheder got this information, as it would appear that Kobitzsch, who helped translate and fill in the form, was the only one who knew of the matter. One possible explanation may be that the German press association deliberately leaked the news to the Danish journal’s Berlin correspondent as propaganda. Berlingske Tidende, the Danish newspaper with which Storm P. had been closely affiliated for more than ten years at the time, spared no time in printing a disclaimer – written by a close friend of Storm P., journalist Busse Drechsel:

In order to be permitted to work for German newspapers and magazines, one must be a member of the Reichsverband der deutschen Presse. And given that Storm P. has been one of the most popular cartoonists in Germany for many years, he has received a request to join the association.

– Do you intend to do so? we ask Storm P.

– No, indeed I do not. If I am to draw in Germany it ought to be enough to bear the name Storm P. and be Danish, and I have no intention of providing proof for the brand name of my bicycle or how many times I have sported a moustache.23

It would appear that Storm P. did not intend to allow a minor untruth to get in the way of his urge to establish that he did not have to prove anything to anyone. The disclaimer also indicates that he felt it incumbent on him to clearly demonstrate that he did not approve of the Nazi regime’s extensive efforts to control the foreign press. Most of all, the matter also seems to have made him more aware of the Nazi ideologies of race, with which he did not wish to be associated, and this may explain why he ultimately abandoned his application for membership.

Accused of anti-Semitism

Approximately two and a half years prior to these events, Storm P. engaged in a correspondence with the eminent Danish director Carl Th. Dreyer, who had suggested that they should make a film together. At a garden party in the summer of 1933 where both men were present, Storm P. supposedly mocked a Danish-Jewish editor, Bertel Bing, by calling him ‘Bertel Fladben’ (‘Flatshanks’). In a letter sent subsequently, Dreyer accused Storm P. of being anti-Semitic and of often placing ‘an unsympathetically caricatured Jewish profile in the very foreground’ of his drawings.24 Storm P.’s reply to these allegations is presented here in full:

Dear Carl Th. Dreyer

Your letter saddened me greatly – I certainly never intended to hurt anyone, least of all B.B., of whom I am very fond and who was once an excellent editor to me. And I have nothing against the Jews whatsoever, I have many good friends among them. If I have created drawings of the kind you describe, I am unlikely to have had Jews in mind – simply a man with a large Nose – I am a cartoonist and poke fun at many things – but my objective is not to hurt anyone.

Chaplin is Jewish himself – he caricatures extensively – the flat feet – and I did not know that B.B. was ever called the nickname you mention.

Blix’s drawing was a strike against Hitler – not against the Jews – and the Jews have flat feet and big noses, there is nothing to be done about that – just as a German has a buzz cut and a beer gut – an Englishman wears plaid patterns and so on – all of these are things that have become standard for all cartoonists.

But to hurt anyone with my drawings – or by what I said (with no malicious intent whatsoever) – no, I would not do that knowingly – I thought you knew that.

What the magazines write and do, they have to do in order to exist at all – we all need to do certain things to exist, and hence mankind are not angels.

I hope, my dear Dreyer, that the two of us may understand each other well in all matters; I would be only too pleased to try to create a manuscript and would only ask you to wait a little while.

Believe me – you attach an entirely erroneous significance to the small incident in Locher’s garden – I may have spoken clumsily – but maliciously? – no, no, no.

Many kind regards to you and your wife

From my wife and your devoted

Storm P.

In the early twentieth century, it was quite natural for cartoonists in all parts of the press, whether bourgeois or socialist, to depict Jews as unlikable characters, as usurers and capitalists with large, hooked noses, thinking only of money. Other ethnic groups were not spared, either; for example, Storm P. pulled no punches when depicting black people in connection with the sale of the Danish West Indies in 1917.

The very first drawing that Storm P. ever had published was a caricature printed in Dansk Slagteri-Tidende (The Danish Abattoir Journal) (5 January 1902), depicting council member Gustav Philipsen, who had enraged the meat industry by proposing that the local authorities should buy and butcher cattle themselves (Storm P.’s father was a butcher). Neither the drawing nor the text accompanying it left any room for doubt that the unpopular local politician was Jewish. The decades that followed would occasionally throw up anti-Semitic drawings from Storm P.’s hand – especially around the time of World War I, where one of his favourite motifs was unscrupulous profiteers, known as ‘gulasch barons’ in Danish, who were often portrayed with large ‘Jewish noses’. [fig. 9]

When the consequences of the racist Nazi policies became generally known, most Danish cartoonists gave up anti-Semitic jokes – including Storm P., whose circle of acquaintances did indeed, as stated in his letter above, include several Jews. Thus there is nothing to suggest that personal anti-Semitic views underpinned the obviously racist drawings he produced at the beginning of the century. However, the concluding words of the letter, ‘we all need to do certain things to exist, and hence mankind are not angels’, are probably crucial for the proper understanding of Storm P.’s dispositions in the 1930s and during the German occupation of Denmark. The fact that the Nazi regime was brutal and oppressive was in no way unknown to the Danes. However, up through the 1930s the Danish government repeatedly stressed to the press that the great neighbour to the south should not be provoked.25 Germany’s power and strength was awe-inspiring, and most Danes, including the uppermost echelons of society, had to take a soberly realistic approach to the apparent fact that at the outbreak of World War II, Germany was poised to become the dominant European power and would win the war within a very short span of time. Not until 1943 did it become clear to a majority of Danes that the tide had turned against Germany’s war effort.

If filling in an application for membership of the German press association could secure one a considerable source of income and a major contribution to one’s pension fund, it seems only human that one would initially tend to overlook the unpleasant implications inherent in having to account for one’s ancestry through several generations. Storm P. was always the first to mock absurd bureaucracy, and he could not possibly have been ignorant of the state of affairs seen in Germany in 1935. However, we should remember that the product which Storm P. sold to Germany consisted in absurd comic stories and humorous cartoons. In retrospect his attempt at joining the association certainly seems blameworthy, but Storm P. does not seem to have recognised that his presence in German media might be construed as implicit support of Nazism. Rather, his ambition to have a major breakthrough in Germany, a country traditionally steeped in civilisation and culture, seemed within reach. Storm P. was far from blind to all the compromises that life throws up in terms of maintaining one’s personal integrity. [fig. 10]

Finances and ambitions

The extensive sales of drawings and stories to Germany that took place in 1929-34 with the aid of Kobitzsch were a source of substantial extra income for Storm P. At this point in time his activities in Denmark and the rest of the Nordic countries were so comprehensive that he was not financially dependent on this additional income. However, Storm P.’s contract with Berlingske Tidende did not include any pension plan. Even though Storm P. and his wife, Ellen, were comfortably off, everyday life in the 1930s was tinged by a pervasive atmosphere of economic crisis and unemployment. Hence, it is quite understandable that at an early point of this decade, Storm P. dedicated some effort to putting aside money for his and Ellen’s old age.26

Career ambitions also seem to have been part of Storm P.’s motivations in connection with his activities in Germany. As was mentioned above, Storm P. looked abroad at an early stage of his career, seeking to contribute to magazines outside of Denmark. His faith in an international breakthrough also came to the fore in his trip to America in 1919, and in 1927 he rather curiously announced to the press that he would emigrate to Paris.27 The plan was to dedicate himself entirely to drawing and painting. Finally, it should be noted that such dreams about international recognition of Storm P.’s great standing as an artist and humourist were not just Storm P.’s own; they were greatly reaffirmed by his immediate family, by the marketing materials accompanying his performances and publications, by his circle of acquaintances, many of whom were leading figures on the Danish cultural scene, and by large parts of the Danish press. In many ways Storm P. was a brand, an example of Danish identity, humour and quality that people were keen – and would be proud – to see succeed abroad.28

Nordische Gesellschaft

The Nordische Gesellschaft was founded in Lübeck after World War I as part of the overall efforts to restore the economic and cultural importance that the Hanseatic cities had previously enjoyed in the Baltic region. At first the society’s activities were mainly concerned with mercantile affairs and trade policy. Art and culture were also addressed, but on a comparatively minor scale. And even though certain worldviews would sporadically emerge in the society’s written materials, the Nordische Gesellschaft remained more or less apolitical up until 1933. [fig. 11]

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, a decision was made to transform the Nordische Gesellschaft into a vehicle for racial ideology propaganda. The task fell to chief ideologist Alfred Rosenberg, who took his starting point in the so-called ‘Nordic theory’ – a popular race theory that became an integral part of National Socialism over the course of the 1930s. The ‘Nordic theory’ was encapsulated by the following four tenets:

1. The Nordic race is of unique and crucial value.

2. The Nordic race is threatened by destruction. By ‘destruction’, we particularly mean its physical demise as a race, but also the loss of Nordic dominance and total alienation from itself due to influences from foreign races.

3. The destruction of the Nordic race would spell the end of Western European civilisation and, hence, all culture.

4. Thus, it is necessary to prevent the destruction of the Nordic race and, hence, the destruction of Nordic culture.29

Based on this description of the Nordic theory, a close relationship with the Nordic countries was virtually a prerequisite for the final victory of National Socialism. Only when Germany’s spiritual revolution had spread throughout Scandinavia could the common Germanic worldview act as the foundation for realising the visions of National Socialism.

Outwardly, however, the Nordische Gesellschaft still seemed to be preoccupied only with mercantile and cultural matters. The plan was to use the cover of cultural-political propaganda to introduce the new Germany to as many representatives of Scandinavian cultural and intellectual life as possible, prompting them to take part in the society’s events. [fig. 12 og 13]

When the Nordische Gesellschaft’s annual rally was officially opened this morning, the backdrop to the speaker’s tribune was a vast flag showing the swastika, surrounded by smaller Scandinavian flags and the society’s own flag, featuring a Nordic sundial. In the streets of the city the flags of the Nordic countries could be seen hanging among numerous swastika banners.30

In the 1930s the society held annual large-scale assemblies, Reichstagungen, in Lübeck. Scandinavia was generally strongly represented at these events, and the contingent of Danish participants over the years included the writers Leck Fischer and Svend Borberg, the prominent gymnastics instructor and public figure captain Jespersen, and the artist Annemarie Carl Nielsen, widow of Danish composer Carl Nielsen.

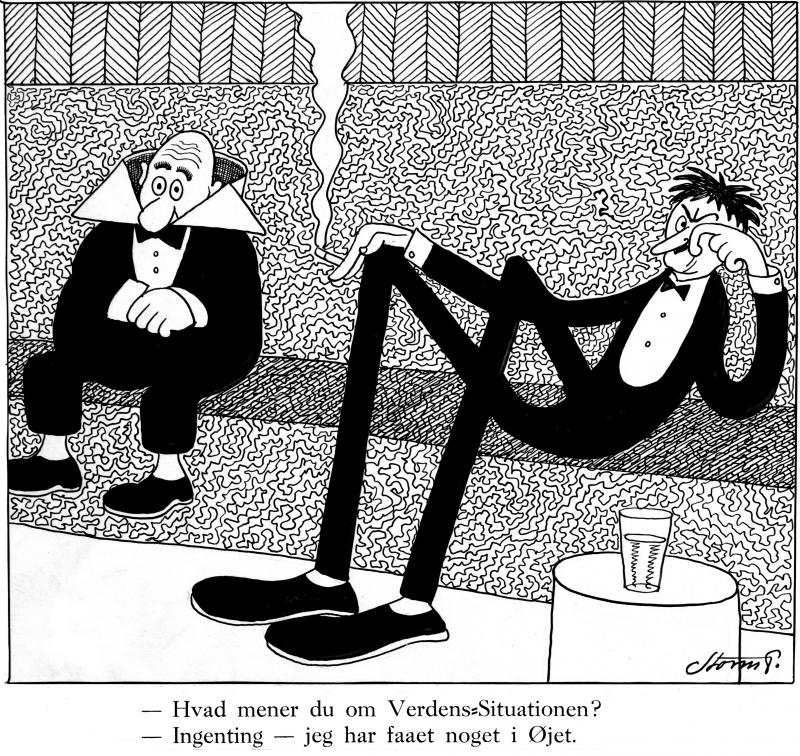

Fig. 14. – What do you think of the current world situation? – Nothing, I’ve got something in my eye. Storm P. Album 1937, p. 20, since then reproduced in a wealth of contexts. Photo: The Storm P. Museum.

Storm P. and the Nordische Gesellschaft

On 1 April 1937, Storm P. joined the Nordische Gesellschaft. It is difficult to determine the exact reasons behind his decision. However, his many other, roughly contemporary efforts to sell his works abroad might suggest that this, like the attempt to become a member of the Reichsverband der deutschen Presse, was yet another strategic move intended to improve his opportunities for selling drawings in Germany. Storm P.’s eagerness to continue his exposure abroad is also evident in the fact that on 19 July of that same year he entered into a contract with a person known as director Bolvig (Viegand Moritz Bolvig, 1905–45), who was given exclusive rights to selling Storm P.’s drawings and other materials abroad. Bolvig was provided with a number of drawings and other materials with which to work, including Storm P.’s correspondence with the Reichsverband der deutschen Presse (which had by this time fallen under the auspices of the German Ministry of Propaganda). Bolvig, who cut the dashing figure of a larger-than-life business man, supposedly held the rights for Disney’s productions in Denmark. However, he never honoured his agreement with Storm P., and the contract was revoked when Bolvig was arrested in Paris the following year, accused of and sentenced for fraud.31

Ahead of joining the Nordische Gesellschaft, Storm P. exchanged letters with the society’s business manager Ernst Timm, inquiring into the opportunities for exposure in German magazines. This is to say that after the failed attempt at joining the press association, Storm P. may have regarded membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft as an alternative stamp of approval that would facilitate trade with Nazi Germany so that the popularity he had enjoyed south of the border just a few years previously could be restored – without, however, taking part in the agendas of race ideology. It is not unlikely that the Nazi plans to control European caricature propaganda were already in the pipeline at this point, and that Timm discreetly let slip to Storm P. that joining the Nordische Gesellschaft would admit him to this market. Such speculation must, however, rest on circumstantial evidence only since it has not been possible to unearth specific testimonials concerning such an agreement. [fig. 14]

When the tides of the war turned in 1943 and the German Ministry of Propaganda chose to dispense with Timm’s services – which had been lucrative for him – he requested permission to continue to sell drawings from his Lübeck office under the name Interpress.32 The Berlin office had mainly worked with propaganda-related trade in caricatures and with checking and controlling such cartoons, a task conducted in close co-operation with the ministry, which also funded the endeavour. By contrast, the Lübeck office was a commercial business (receiving no ministerial funding) where the main purpose was not propaganda, but quite simply to make money from the international sale of cartoons, humorous stories etc. to the press. [fig. 15]

As mentioned above, in 1930 Storm P. took part in an exhibition about Nordic caricature and cartoons arranged by Nordische Gesellschaft in Lübeck. In his opening speech for this event, Ernst Timm described Storm P. as ‘an artist of international significance’. From this point on, the Danish cartoonist’s work was regularly featured in publications issued by the Nordische Gesellschaft. And in 1935 he received a letter from the society concerning the purchase of drawings; a letter that Adolf Kobitzsch translated and deemed very promising, stating that ‘something might well come of this’. This is to say that Storm P. had already had dealings with the society for years when he signed up as a member in 1937, and that he knew Timm as a man who was very favourably disposed towards him. Finally, it should be noted that at this time the Nordische Gesellschaft still appeared to be a relatively harmless, apolitical entity. Storm P. and Ernst Timm remained on cordial terms even though the Danish humourist consistently rejected the repeated attempts at persuading him to take part in the society’s events. Timm even offered to place a private airplane at Storm P.’s disposal so that he could visit the society’s/Rosenberg’s lavish 1937 rally in Lübeck. But to no avail. From the time Storm P. joined the society in 1937 up until the end of the war, he did not take part in any of the events arranged by the Nordische Gesellschaft in Denmark or Germany. Nor did he ever speak publicly about the society or about political subjects in general. And all of the drawings and texts supplied by him were entirely apolitical. [fig. 16]

By this time Storm P. had long since withdrawn from political newspaper satire. From the 1920s onwards, his role in BT and other Danish media was primarily that of a humourist. Thus, his contributions to the press may at first glance appear to be harmless entertainment when compared up against the political satire of Bendix and similar artists. However, such a comparison would be unjust given that these two cartoon disciplines differ from each other in many essentials.

The high membership fee

The fact that Storm P. paid an unusually high membership fee is yet another aspect of this matter that has proven impossible to fully explore. Standard members would usually pay between DKK 10 and 25 every six months. Storm P. and sixteen other members paid DKK 100 every six months (corresponding to more than DKK 7,000 / EUR 1,000 in current prices). Also puzzling is the question of why he did not resign from the society when Denmark was occupied by German troops on 9 April 1940 – or when the Danish government’s co-operation with the German occupation collapsed in August 1943, at which point the Nordische Gesellschaft, as well as all other associations related to Nazism, saw a great number of members leaving. However, Storm P. never withdrew his membership and continued to pay his membership fee up until 1944, when the Nordische Gesellschaft ceased operation. One explanation may be that drawings were still being sold continually via Nordisk Pressefoto, operated by Carl Kyhne (owned by Berlingske Tidende) and the German agency Interpress, operated by Ernst Timm and Rittmeister Schaeffer. If this trade had originally been made possible by Storm P.’s membership of the society, either directly or indirectly, it does not seem unreasonable to suppose that Storm P. elected to leave things as they were – as part of a set of agreements – without thereby indicating any particular personal sympathy for the society.

This assumption is borne out by the fact that the sixteen other members who paid correspondingly high membership fees were all companies. Many of these were large enterprises, including Den Danske Landmandsbank, De Danske Spritfabrikker, Danske Oliemøller og Sæbefabrikker, Nordisk Film A/S, Persil – Fa. Henkel & Co., Dansk Cement Central and Agfa Foto A/S. Enterprises that had a crucial interest in being able to act internationally. Several of these companies joined the society prior to Storm P., and only one of them withdrew again (Poly foto, in 1943). Seen in this light, the idea that Storm P.’s high membership fee was paid out of a simple desire to support the society as a private individual seems quite naïve. Rather, the evidence suggests an agreement concerning corporate membership of the society. However, this cannot be corroborated by the membership list, surviving letters or any other documentation. Nor has it been possible to gain access to Storm P.’s bank statements to trace any possible connection between his membership of the society and his professional dealings with Nordisk Pressefoto (Nordfoto) and Interpress.

It would appear that to Storm P., joining the Nordische Gesellschaft seemed ethically more sober/apolitical than membership of the German press association; a better way of facilitating commercial dealings with Germany.

The Nordische Gesellschaft in Denmark

A total of 247 names were featured on the Nordische Gesellschaft’s list of Danish members. The earliest date of joining was 20 October 1931, the latest 25 May 1944. Generally speaking, the members belonged to the upper echelons of society: bank managers, merchants, manufacturers, aristocrats, senior doctors and similar professions. In addition to this, the members included a number of figures from the cultural scene and the aforementioned enterprises.

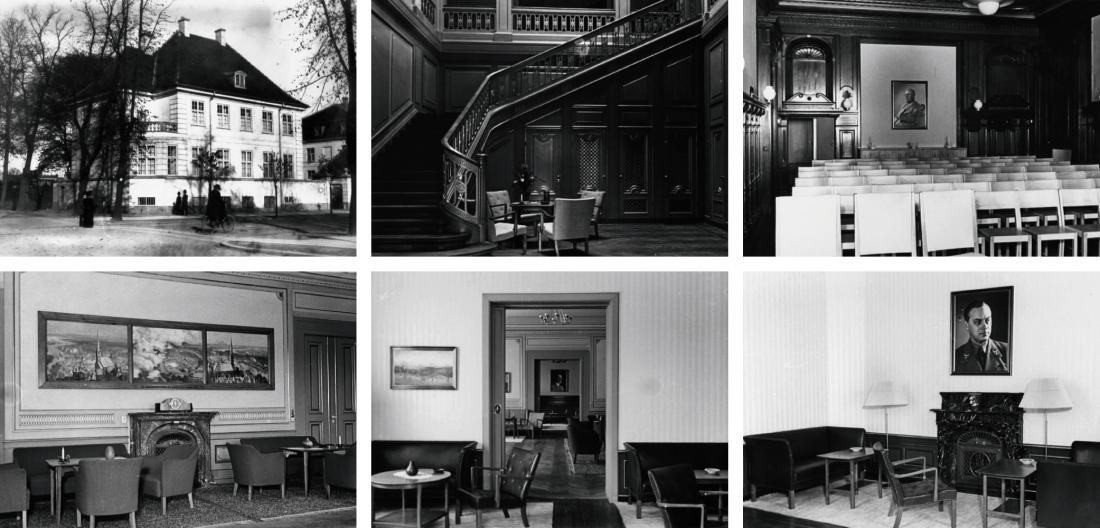

In 1940 the Nordische Gesellschaft bought a large house, known as the Otto Mønsted Villa, in Kristianiagade in the Østerbro area of Copenhagen in order to be represented in the Danish capital. At the behest of the Danish president of the society, Ernst Schäfer, the event was celebrated in October of 1940 with a tea reception at Restaurant Wivex. Approximately 100 guests were invited, most of them members of the society. The attendees included minister of foreign affairs Eric Scavenius, national police commissioner Thune Jacobsen, the director-general of the Danish railways, and figures from the realms of commerce and literature, including the writers Svend Borberg, Svend Fleuron, Hakon Stangerup and others. Storm P. was invited, but chose to decline. [fig. 17]

April of 1941 saw the opening of the Nordische Gesellschaft’s ‘Dänemark-Kontor’ (Danish Office), and Schäfter showed the premises to the Danish press at a social event on 17 September. Every Tuesday the office held evening events for members that included screenings of films about German culture and propaganda films. In addition to these members-only evenings the office also hosted larger events featuring artists and lecturers from Germany and Scandinavia. Danish and German radio broadcast regularly from these events. [fig. 18] In March of 1945 the German occupation forces decided to convert the villa in Kristianiagade into a hospital for wounded German soldiers. Orders were issued for all important papers to be burnt or sent to Germany. However, the list of members avoided the fires, was kept concealed by a female secretary and ended up in the hands of the Danish newspaper Dagbladet Information. In November–December 1945 Information ran a series of articles about the Nordische Gesellschaft with a view to publishing the entire list of members. The first article in the series describes the members of the society as follows:

This list contains a most peculiar mixture of names: members of the Hipo corps, German Nazis, otherwise well-respected bank managers and eminent businessmen all entwined. Some of them joined the society several years before the war, and we are happy to overlook them here, even though one might well wonder at what kind of ‘culture’ an eminent artist such as Robert Storm Petersen could find to exchange with Nazi Germany. We are also willing to leave sleeping dogs lie when considering the fact that prior to the war, some Danish companies and institutions saw a certain commercial interest in supporting an at least outwardly harmless entity such as the ‘Nordische Gesellschaft’. A few members left on 29 August, but the rest, among which one does, of course, find Scavenius and Chr. H. Olesen, continued to pay their membership fees until the end. However, things are very different for those who joined immediately afterwards and during the Occupation. And this holds true for most of them.33

On 30 November 1945, Dagbladet Information suddenly stopped their reports on the matter, presumably following a request from the Danish state authorities or intelligence services. Today, the list of members can be found in the Danish National Archives, where it is classified as ‘restricted’ (‘Ikke umiddelbart tilgængeligt’, literally ‘not immediately accessible’). [fig. 19]

During the backlash against the collaborationists (so-called ‘værnemagere’), many Danish cultural organisations conducted their own internal trials and excluded members who had had dealings with the Nazis. These included Dansk Forfatterforening (The Danish Authors’ Society) and Skuespillerforbundet (The Danish Actors’ Association). Incidentally, Storm P. was a member of both. Those who were excluded were subsequently derided in the press, could no longer find work and would typically remain branded by this stigma for decades. For example, this applied to two of Storm P.’s close acquaintances, the actor Christian Arhoff (1893–1973) and the art historian Vilhelm Wanscher (1875–1961), who had joined the Danish Nazi Party. Membership of the party can only be regarded as considerably more compromising than membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft. However, in view of the almost euphoric frenzy of vengefulness that held sway in Denmark in 1945–50, it is remarkable that no-one reacted to Dagbladet Information’s revelation concerning Storm P.’s membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft. In fact, quite the opposite occurred: Storm P. was more popular than ever, and a few years later he received the Order of the Dannebrog from king Frederik IX. Upon presenting Storm P. with the order, the king added that he did so ‘in gratitude for all you have meant to the Danish people during the occupation.’ And even though Information’s article has been accessible to everyone since then, more than sixty years would go by before the music historian Lasse Olufson once again called attention to Storm P.’s association with the German society.

The press agency Interpress

In November of 1938, eight months after Bolvig’s contract was annulled, Storm P. received a letter from the Danish president of the Nordische Gesellschaft, Rittmeister Schäfer, informing him that after having stepped back as the society’s business manager, Ernst Timm had founded a European press agency, Interpress, which wanted to do business with him. The missive was written on paper bearing the Interpress letterhead, and Schäfer introduced himself as the agency’s Danish representative. On behalf of Timm he offered to sell Storm P.’s cartoons in Germany in exchange for granting Interpress exclusive rights to these cartoons throughout Europe (excepting Denmark). It was suggested that the profits from the sales should be split 50/50. After a certain amount of correspondence back and forth between the two, Storm P. left the negotiations to Berlingske Tidende, with which he was contractually bound, and where the management included several of his close friends.34 An agreement was eventually reached between Interpress and Berlingske Tidende, and from this point on Storm P. would regularly receive money from sales made to ‘Interpress, Lübeck’. Right up until 1944 a significant number of cartoons was sold via these channels.

Today we know that during this period Schäfer and Timm also approached other Danish cartoonists with similar offers. Feeling that something was off about these proposals, two of these cartoonists contacted the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. One of them, Hans Bendix (1898–1984), was a Social Democrat, a Jew, and highly critical of Nazi Germany.35 Strangely enough this did not seem to bother Schäfer and Timm, who were willing to deal with him in spite of these facts. What is more, Ernst Schäfer had, ever since Hitler’s takeover, been publicly known for a series of newspaper articles, especially in the official Nazi organ Völkischer Beobachter, criticising Danish politicians and especially the Danish press, which he claimed was ‘contaminated’ by Jews and Bolsheviks. Schäfer was also suspected of spying with a view to a subsequent German invasion (suspicions that would later prove to be accurate), and in 1936 several Danish politicians demanded that he should be deported from Denmark. Ernst Timm was also known as a vociferous agitator for National Socialist ideas. Ever since the mid-1920s, the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs had their sights on Timm, suspecting him of being the architect behind German propaganda and a man who would use any means necessarily to reach his objectives. Among his tools were the Nordische Gesellschaft:

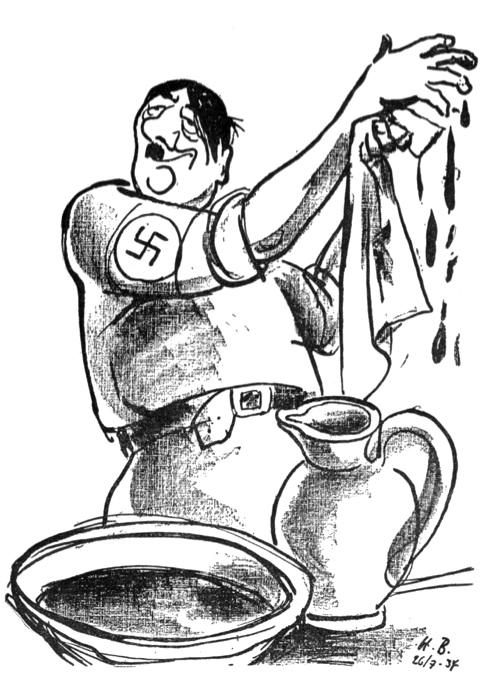

Dr Timm is a fervent Nationalist and possessed of an insatiable ambition which is accompanied by an equally insatiable desire to make money. […] As the honoured Ministry will recall from many previous occasions, Dr Timm is fond of appearing in various guises, thereby giving his ventures the appearance of being to the advantage of, by turns, Denmark, Sweden and Finland.36

This is to say that the Danish authorities had ample reasons for being suspicious of these two German gentlemen and their intentions. Letters exchanged between the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Danish Legation in Berlin show that the authorities were entirely aware of what was really happening.37 Having resigned as business manager for the Nordische Gesellschaft, Ernst Timm was employed by the German Ministry of Propaganda, with which he entered into a written agreement in 1938, charging Interpress with organising and controlling caricature propaganda in German and abroad by buying up cartoons and rights at the ministry’s expense. This was done under the auspices of Politische Zeichnung Interpresse, which set up an office in Berlin near the Ministry of Propaganda.38 At the same time Timm continued to operate his own business, Interpress, Europäisches Pressebureau, out of his office in Lübeck. The sales of Storm P.’s materials appear to have taken place within this part of his business. Timm not only acquired materials that were intended to be disseminated for propaganda purposes: the fact that his contract with the Ministry of Propaganda stated that Timm should acquire the rights to the cartoonists’ works suggests that the control aspect was essential to them. The objective was to seize control over the work created by cartoonists such as Bendix, thereby ensuring that they could not be published in countries that were hostile to Germany (In 1935 Bendix had outraged the Nazis with a particularly ‘disrespectful’ caricature of Hitler shown with his hands dripping with blood).39 [fig. 20]

The other cartoonist to approach the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Norwegian-born Ragnvald Blix (1882–1958), ‘could also be described as “’unerwünscht” [unwanted] in Germany’, as he himself put it in his message to the ministry. Shortly afterwards Bendix and Blix both had to flee Denmark, one escaping to the USA, the other to Sweden. The evidence available suggests that Storm P. was the only Danish cartoonist to enter into a binding contract with Interpress and Timm. However, as was mentioned in the above, the practicalities associated with this contract were taken care of by his friends at Berlingske Tidende, particularly by editor-in-chief Svend Aage Lund and the director of the paper’s image agency, Carl Kyhné, who had several meetings with Ernst Timm in Copenhagen. It should be added that Timm regularly visited the newsroom of Danish newspaper Politiken in Copenhagen to buy strips by the cartoonist Ingvar as well as various articles on apolitical subjects. So it would appear that this rival newspaper also had no compunctions about dealing with the Germans.

When Storm P.’s cartoons and stories were introduced in German magazines they would occasionally be accompanied by a text about the famous Dane. In these captions he was often described as the greatest humourist in Denmark. This claim is in keeping with the general Danish view of Storm P., whose gentle wit came to constitute a much-needed spark of light for many Danes during the dark years of German occupation. Speaking of his role as a humourist during the war, Storm P. himself stated that he could ‘soften’ things. And we see that these soothing properties of his humorous cartoons and stories also made them marketable in Nazi Germany. Retrospectively, this is a paradox, and one which is unlikely to have left the old cartoonist’s self-image entirely unscathed during and after the occupation years.

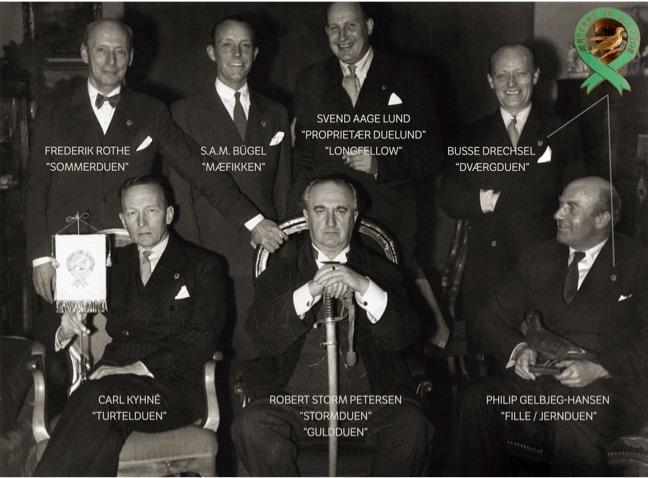

Berlingske Tidende, the ‘Doves’ and the Danish-German Society

Everybody wanted a piece of the popular humourist. And Storm P. did not only form professional ties with the Berlingske media concern. In the early 1930s he formed personal friendships with a range of individuals from the company’s management tier, including editor-in-chief Svend Aage Lund (1900–81); the director of the newspaper’s image agency, Carl Kyhné (1890–year unknown), editor at Berlingske Aftenavis Busse Drechsel (1888–year unknown) and former bank manager of Landmandsbanken Frederik John Rothe (1884–1962), who had married into the Berling family and now sat on the newspaper’s board of directors. Together with the barrister S.A.M. Bügel and the steel merchant Philip Gelbjerg-Hansen, these gentlemen formed a society or informal member’s club in 1939. Known as ‘Skovduen’ (The Wood Pigeon), the society met twice a month for the next seven years to eat, drink and discuss current affairs. Storm P., who was the club’s president and central figure, kept meticulous notes on these gatherings in small exercise books. However, the detailed descriptions tended to focus on the food and drink being served. [fig. 21]

From the 1930s onwards, Svend Aage Lund, whose archives could regrettably not be accessed while researching this article, very ably steered the ‘Berlingske Hus’ towards becoming a modern media concern. From 1935 he held the function of editor-in-chief. He did not write himself, but nevertheless he was considered the most powerful man within the Danish press for decades, acting as spokesman for the nation’s pre-eminent magazine and newspaper group.40 In the summer of 1940, Svend Aage Lund and the German press attaché, Gustav Meissner, were co-founders of Dansk-Tysk Forening – the Danish-German Society. The idea was realised by the Danish government, led by Stauning: as a token of its willingness to co-operate with the Germans, the Danish government wished to create a forum for Danish-German interaction that did not involve the Danish Nazi Party.41 The society ceased operations after 29 August 1943. After the war, Svend Aage Lund was widely criticised for having taken this step and for the very German-friendly line taken by Berlingske Tidende up until and during the occupation. However, he managed to weather this storm with the support of the paper’s board of directors, maintaining his position of power until he retired in 1970. In other words, Storm P.’s wassailing comrades were not just anybody. He was very closely acquainted with some of the most influential figures in the country; figures who had direct access to the Danish government.

Storm P.’s political views

As was mentioned above, the young Storm P. was affiliated with many different journals and newspapers that held varying political views. His own background was conservative, a fact that is borne out by his choice of the traditionally conservative Berlingske Tidende newspaper as his regular place of work from 1922. The archives at The Storm P. Museum have documentation proving that he was a member of the Danish Conservative Party’s voters’ association from at least 1935 onwards.42 The distinctive humanism that often finds expression in his art and humour as a keen eye for individual and unique characters in the midst of blandly uniform masses can easily be reconciled with conservative political views. This was an individualistic vein of humanism, based on the premise that we are all share the common experience of being alone in a very complex world. Some are able to recognise this fact, (many) others walk through life ‘blind’. Something similar applies to his entrepreneurship and his self-image as a ‘self-made man’ who had achieved his successes through hard work. Certain indications suggest that he sympathised with the most right-leaning wing of his party on some issues. For example, in 1939 he supported Dansk Skatteborgerforening (the Danish Taxpayers’ Association), which was part of a conservative movement that took a critical view of parliamentarism. This should presumably, particularly in the case of Storm P., be regarded as an expression of concern of how parliamentarism presents a risk that mass movements – whether Communist or fascist – can usurp power and create oppressive mass societies. Storm P.’s friendships with Christian Arhoff and Vilhelm Wanscher and with the extreme right-wing Swedish artist Ossian Elgstrøm (1883–1950) might also suggest sympathy with far-right points of view. However, his circle of friends also numbered a very large number of people with quite opposite political views. Finally, his art signals anything but sympathy with totalitarian modes of rule.

Humourist

Even though Storm P. was reluctant to describe his own activities and often took an ironic point of view when asked, his statements suggest that he primarily saw himself as a humourist and caricaturist,43 working within the time-honoured tradition of caricature with its ideals of stripping away outward appearances and looking beneath the veneer and glamours of culture. There are several instances of Storm P. describing humour as a kind of worldview. A special outlook on life and the world that he held to be something other and greater than satire; something which he tended to regard as a tool used to serve specific purposes. Political satire never became his field. Quite the contrary: his production reflects a wish to speak to a basic humanity rather than to advocate particular political beliefs. This undoubtedly also contributed to the high esteem he enjoyed among a very broad audience. [fig. 22]

I am a humourist! But in fact being a humourist requires you to be a very serious-minded human being. If a humourist is to achieve something that reaches beyond the immediate moment, then he must approach his work with the deepest gravity, for only against a backdrop of seriousness does humour work as it should. […] …one looks behind it all, behind the surface of people and things, and this does not make for any particular lightness of spirit […] I have an ability to amuse other people. Of course this is a gift – a gift for which I am grateful! But it is not always an unalloyed pleasure for myself […] Great comedy can only be achieved through deliberate effort, and the comedy that delves deepest can only be created by the serious man who looks behind it all – right down to the bottom of things; then he becomes a humourist.44

One should, of course, be wary of equating the views expressed in a cartoon with the cartoonists’ own private views. If one did that with Storm P., it would be possible to attribute virtually any position to him as one traverses the approximately 60,000 cartoons he is conservatively estimated to have published during his career.45 Storm P. had quite a satirical bite to his cartoons during the first decades of his career. However, it would be wrong to specifically foreground him as a social satirist. Even so, Storm P. was among Denmark’s most progressive cartoonists, editors and artists during the first decades of the twentieth century.

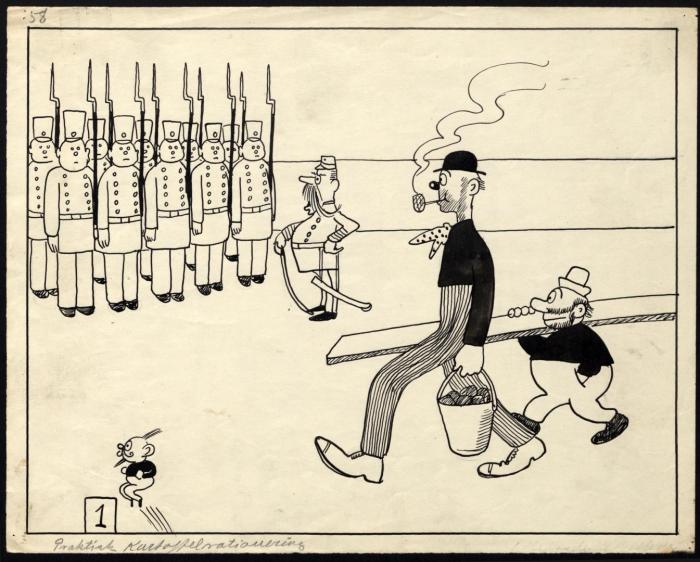

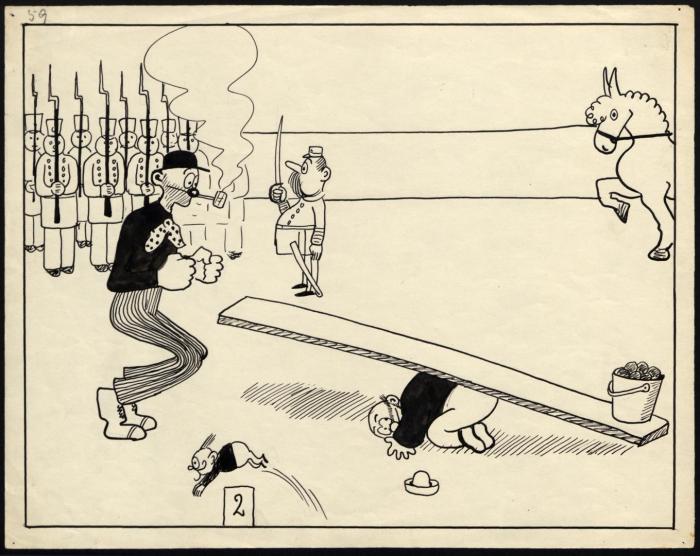

The artistic legacy

When one looks at Storm P.’s humorous cartoons and at his paintings, one will usually find pompousness and uniformed authority ridiculed. In Storm P.’s work a general or despot is never cast as the hero. [fig. 23a-d] That distinction falls to perfectly commonplace, ordinary men (who incidentally often turn out to be anything but ordinary when one looks behind the veneer of normality). This everyman character is the one who sees the world rush by at a speed he cannot handle or get a grasp on. He must greet external circumstances with a kind of humorous stoicism or perish in the maelstrom of modernity. The everyman character or free vagabond is emphatically himself in a world characterised by uniformity, by the trappings and institutions of civilisation. Institutions that Storm P. often exposes as being essentially absurd on closer inspection. A good example of this negative view of civilisation and idealisation of the marginalised is the painting Indenfor og udenfor (Inside and Outside) from 1938. [fig. 24]

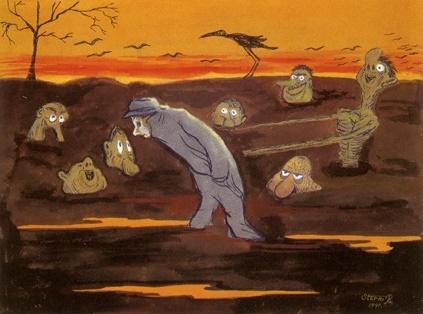

Storm P.’s art from the late 1930s and the occupation years is, like much other art from the time, introspective. The watercolour Sunset, 1941, depicts a lonely, anonymous wanderer with a masklike face walking through a muddy, desolate landscape of doom. The swamp is peopled by fools who appear to be perfectly content to be mired in the mud. They either eye the wanderer suspiciously or reach out to pull him in. The air is full of ominous black birds. This is the Evening Land – the end of Western civilisation. Storm P.’s art from this period can be roughly described as portrayals of the grotesque state of the world. An imbalance between human toxicity and nature’s absolute goodness. His humorous output often has its subtle wellspring in the self-same sombre source. [fig. 25]

As was mentioned above, a number of Storm P.’s stories were printed in the eminent German satirical magazine Simplicissimus. The last one of these (10 December 1941) is the story Behörden (Kontorer, meaning ‘Offices’, 1936), a shrewdly witty Kafkaesque nightmare about Mr Uldknabe, who has to go from one absurd office to another in order to obtain a life certificate. When he finally reaches the right office he falls to the floor, dead, and is not discovered until closing time. An office clerk exclaims: ”Uldknabe? – Den Namen kenne ich gut – hier liegt ja eine Lebensbescheinigung und wartet auf ihn.”46

Given the matter discussed here, this work of satire ably illustrates Storm P.’s point of view. A small, ordinary man spends his entire life obtaining a permission to live – while ceaselessly confronted by a society of bureaucrats and absurd societal institutions which, alongside his own inability to find liberation, are essentially the cause of his misery. The theme can be regarded as a social critique that might well be directed against Nazi society, but also against any other bureaucratic system that oppresses individual freedom. The fact that the story appeared in Simplicissimus as late as 1941 also serves to show that the Nazi censors saw no problem with Storm P.’s allegory.

Conclusion

Right from his early youth, Storm P. had ambitions to do well abroad. He formed close links to Germany as far back as 1912 through his links to the magazine Der Sturm. Hence, it seems reasonable to describe Storm P. as positively disposed towards Germany. However, this can in no way be equated with being an advocate of Nazism. The exact reasons why Storm P. became a member of the Nordische Gesellschaft in 1937 cannot be conclusively identified. Extensive circumstantial evidence suggests that business matters played an important part. His membership may have been based on a meaningful suggestion or downright demand presented by Ernst Timm, a precondition for Timm’s promise to consolidate the sale of Storm P.’s cartoons in Germany; sales that had already been ongoing for years. It does not appear that Storm P. sought to stop the sale of his work in Germany at any time.

If we compare his situation to that of corporate enterprises, many companies depended on trade with Germany and had to tread carefully and ‘diplomatically’ in relation to the Nazi regime. The fact that many business owners joined e.g. the Nordische Gesellschaft does not necessarily prove that they had Nazi sympathies. They could not break off their connections with the German market without running the risk of facing serious financial consequences for themselves and their employees. Conversely, there was also a great deal of money to be made for opportunistic businessmen. All this does not change the fact that the connection between Storm P. and the Nordische Gesellschaft is compromising given that the society was obviously under Nazi rule. It is quite unlikely that Storm P. was unaware of this fact. However, this applied to all aspects of the German societal set-up. If you wanted to do business with Germany, you were to some extent obliged to conform to the rigid control mechanisms of the Nazi regime. However, Storm P.’s membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft is not nearly as damning as a membership of the Danish Nazi Party, DNSAP, would be. When considered in light of Storm P.’s other activities relating to commercial launches abroad in the 1920s and 1930s, and the overall outlook reflected in his art and humour, I believe that the decision to join the society was primarily prompted by a wish to assist the sale of cartoons in Germany, not by ideological reasons. The high membership fee indicates that Storm P. acted as a company wishing to do business in Germany. The overlapping memberships found among the management of the Nordische Gesellschaft and the management of Interpress, which handled the sale of Storm P.’s cartoons through Nordisk Pressefoto, support this assumption.

His membership of the Nordische Gesellschaft can be said to place Storm P. within the very large group of what Hans Hertel calls ‘medsvømmere’ in Danish, a 1940s slang term that literally means ‘those who swim along’ or ‘co-swimmers’.47 This group was very wide-ranging in scope. It included famous people from the realms of culture, academia and science, directors of publishing houses and theatres, artists, journalists and figures of no fixed allegiance – as well as the more harmless kind of opportunists who wanted to protect their own best interests if the Germans were to win the war. Up until 1943 many believed they would. Storm P.s business dealings with the press agency Interpress demonstrate that he did not shrink back from doing business with overt, self-confessed German Nazis such as Timm and Schäffer, who had both agitated in favour of Nazism in Danish media and who were even, in the case of Schäffer, known to be a spy; a person whom several Danish newspapers had, prior to the German occupation, demanded should be deported from Denmark. Financial interests and ambitions concerning an international breakthrough set Storm P. on an unfortunate course that saw him end up as an involuntary tool for German propaganda – and what a prize he must have been, this Danish national treasure! Whereas Blix and Bendix were instantly suspicious, Storm P. appears to have taken the bait. But then again he was not a political satirist, but a humorous cartoonist. His drawings, cartoons and stories could be easily translated into German and sold as harmless Danish Gemütlichkeit – cosy, light entertainment – and this was done on a quite extensive scale. He would hardly have thought that the dissemination of his humour could do any harm, and if he did indeed wish to stop the sales at some point, this cannot be proven using the sources available. It is also likely that during the German occupation of Denmark, Storm P. would have regarded a withdrawal of his membership as a risk he did not wish to take. [fig. 26] If we accept this conclusion, it does inevitably point to a very considerable lack of political flair on Storm P.’s part during very difficult times. However, such things are always much easier to see in hindsight. ▢

This article is the result of a process of academic collaboration launched by documentarist Alec Due and Nikolaj Brandt in the summer of 2012. A great deal of initial research in the museum archives was conducted in 2012–13.

Sadly, Alec Due passed away in 2015. This article is very much based on Alec Due’s tireless research, his regularly updated written drafts and indefatigable enthusiasm right until the end. Thank you, Alec. You are greatly missed.

Bibliography

Bay-Petersen, Hans: En selskabelig invitation. Det Kongelige Teaters gæstespil i Nazi-Tyskland i 1930’erne, 2003.

Foss, Amalie and Larsen, Louise C.: Folkets kærlighed vores styrke eller hvorfor bladtegning er kunst, 2010.

Hardis, Arne: Æresretten – Dansk Forfatterforening og udrensningen af de unationale 1945-52, 2003.

Hertel, Hans: Besættelsens kulturliv: Beskyttelsesrum, væksthus, modstandslomme, Copenhagen 2003.

Heuseler, Søren (ed.): Frø af Ugræs; Fascistiske tendenser i mellemkrigstiden, 2008.

Kreth, Rasmus: Pilestræde under pres. De Berlingske Blade 1933-45, 1999.

Kretschmer, Matthias: Der Bildpublizist Mirko Szewczuk, 2001.

Lauridsen, John T. (ed.):Over stregen under besættelsen, 2007.

Malmkjær, Poul: Okkenej, okkeja: komikeren Christian Arhoff – en biografi, 2000.

Nordlien, Niels-Henrik: Træk af den tyske propaganda- og kulturpolitik i Danmark, 1940-1943. En analyse af besættelsesmagtens forsøg på at fremme en tyskvenlig opinion i Danmark, unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Copenhagen, 1998.

Olufson, Lasse: En undersøgelse af Nordische Gesellschafts rolle i kulturudvekslingen mellem Danmark og Tyskland 1930-45 med særligt fokus på musikområdet, unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Copenhagen, 2008.

Plum, Angelika: Die Karikatur im Spannungsfeld von Kunstgeschichte und Politikwissenschaft. Eine ikonologische Undersuchung zu Feindbilder in Karikaturen, Aachen 1998.

Päge, Herbert: Karikaturen in der Zeitung. Eine Undersuchung der Fragen, ob Karikaturen in Tageszeitungen eine journalistische Stilform und Karikaturisten Journalisten sind, higher doctoral dissertation, Dortmund 2007.

Søholm, Ejgil: Storm P før Ping. Bladvid og satire 1902-20, 1986.