Summary

Willy Ørskov’s artistic production has most often been analysed based on Ørskov’s own writings on sculpture. This article explores whether new perspectives on Ørskov’s œuvre can emerge when an analytical approach is taken that differs from Ørskov’s own. The focus of the article is Ørskov’s pneumatic sculptures created in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. These inflated sculptures possess an inherent temporality, potentially offering the viewer an experience of time as a transformative force rather than as an instrument of regulation.

Articles

Willy Ørskov created his so-called pneumatic or inflatable sculptures at the end of the 1960s. All of them are cylindrical sculptures inflated by means of a black rubber valve. They vary in length and diameter. The smallest stand around one metre tall, while one work is more than 25 metres long. Some stand up straight, held in place by a lead base inside the piece, while others are manipulated and posed into particular formations.

In his monograph on Ørskov from 1976, Folke Edwards calls this group of works an ‘anomaly’ and an ‘interlude’ in Ørskov’s oeuvre, which usually sees the artist employ more permanent materials such as metal and stone.1 Another interpretation is also possible: that the pneumatic sculptures constitute Ørskov’s most original contribution to art history. Today, out of all of Ørskov’s sculptures, they are probably also the ones that have the greatest impact on viewers. The pieces are of their time, but they cannot be reduced to simply being typical of the period.

The pneumatic sculptures can be described as casings or containers. Their pared-back, minimal appearance creates a situation for the viewer which is difficult to accurately describe as there is not much on which to pin an analysis. The works are filled with air and can therefore also be emptied again, which gives the works a temporal quality: an aspect of duration. In this article, I will investigate the temporality of these sculptures. My contention is that the sculptures can evoke in the viewer a special experience of time where time is perceived as a continuously changing force. I will examine this through the concept of the time-image found in Gilles Deleuze’s books on film, Cinema 1, l’Image-Mouvement and Cinema 2, l’Image-Temps, published in 1983 and 1985 respectively. Here, Deleuze argues that modern cinema gives rise to images which present time directly to the viewer while time had previously been represented in film. Applying the concept of the time-image, I believe that it is possible to examine the temporality of the pneumatic sculptures anew.

A tableau vivant in Otterlo

Ørskov exhibited pneumatic sculptures for the first time in 1968 at the Spring Exhibition presented at Den Frie Udstilling [Fig. 1]. In a number of solo shows arranged in the following years, he showed exclusively pneumatic works, for example at the Art and Project gallery in Amsterdam (1969 and 1971), the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan (1969), the Jysk Kunstgalleri in Copenhagen (1969), plus-kern in Ghent (1969) and the New Smith Gallery in Brussels (1970). His exhibition in the Danish pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1976 also included pneumatic sculptures, and an exhibition at the Glyptoteket in Copenhagen in 1979 consisted primarily of pneumatic works. Today, examples of this group of works can be found in the collections of Statens Museum for Kunst, Louisiana, Kunsten, ARoS and Sorø Kunstmuseum in Denmark and the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands.

While the works are featured in many collections, they are rarely shown. The latex-based material from which the works are made is not particularly resistant to the ravages of time, and today many of them are leaky, in need of conservation and unfit for public display. At Sorø Kunstmuseum, one such sculpture was shown in 2023 as part of the collection. The museum has previously shown examples of these works in various presentations of the collection. At the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo in the Netherlands, visitors could view a group of pneumatic works at the exhibition The Love of Art Comes First, shown from September 2023 to February 2024 [Fig. 2].2

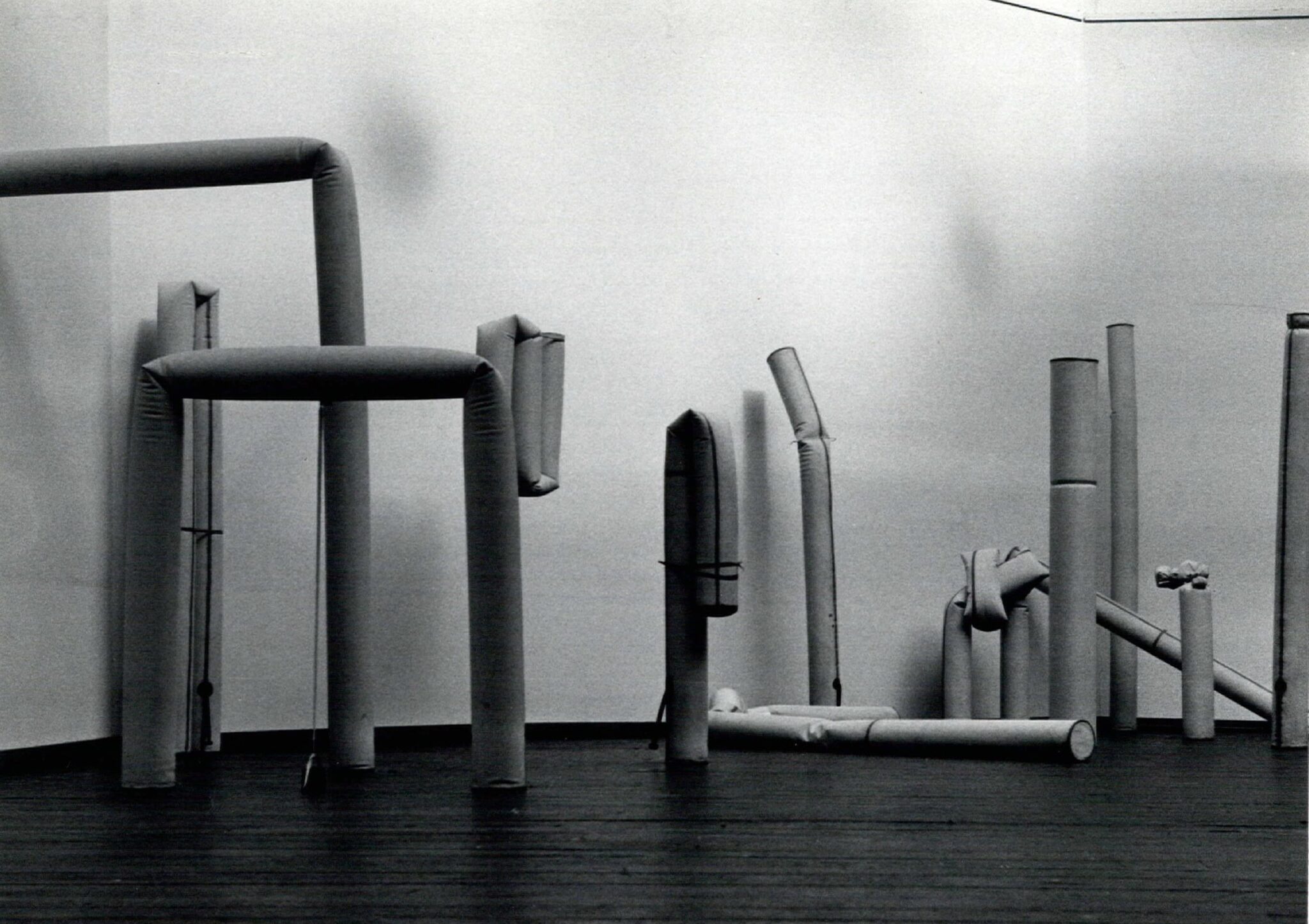

This constituted the first opportunity to view a group of these works since 2016, when several works were shown at Sorø Kunstmuseum. Back in 2012, the museum showed the exhibition Bøjninger / Flexions consisting of pneumatic works which the museum later received as a donation [Fig. 3].3 My starting point for this article will be the show at the Kröller-Müller Museum, as this is the most recent presentation of the group. I will compare the exhibition in Otterlo with previous exhibitions and ways in which the sculptures have been shown, based on the available documentation of these. My analysis will thus be based partly on the individual works and partly on the public presentations of them. I believe that one of the central aspects of these pneumatic sculptures is that they are serial works with variations that become apparent when displayed in groups. The exhibition situation is therefore important and will be the starting point for the article. The individual work and the exhibition of it are different things, but in the case of the pneumatic sculptures the work and its showing are interwoven to a near-inextricable extent, in the same way that a performance piece will always be informed by the particular space and time of its performance.

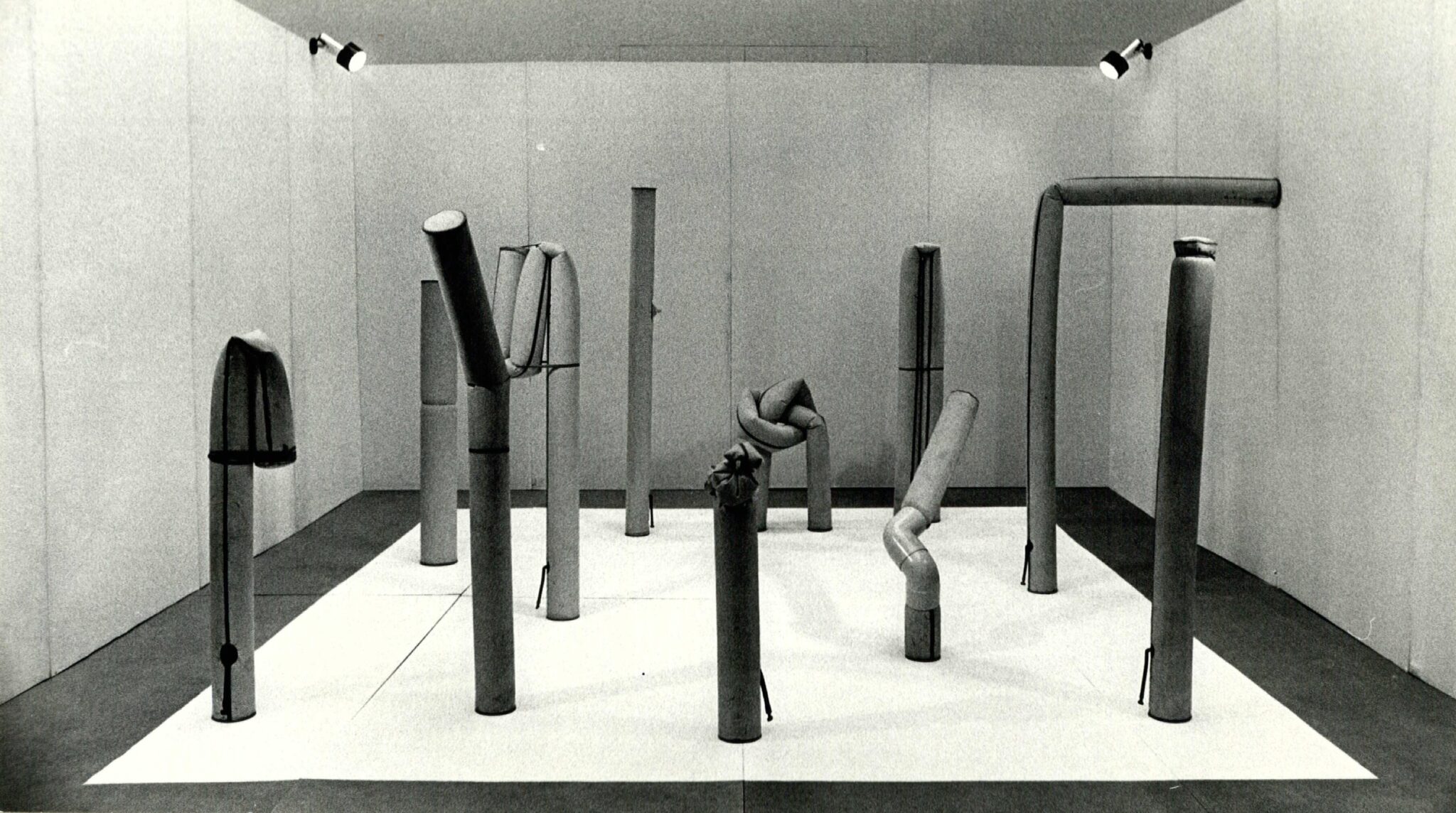

At Kröller-Müller, all of the museum’s six inflatable sculptures were displayed. Together, they unfolded the diversity found within these works: while one stood upright, two other sculptures were tied with ribbons and thus manipulated to bend in certain places. One sculpture was not completely filled with air, causing its upper part to lean at an angle. One stood at a 90-degree angle with one end against the wall, while another formed a bridge or gate [Fig. 4]. The formations of the individual works are all familiar from various photos of previous exhibitions where Ørskov personally arranged the works. Three sculptures were left unpainted, showing the beige material, while the other three were painted in various colours. However, the paint had cracked in the intervening years, revealed how they had been kept uninflated and folded up for a long time. Now, they were briefly unfolded and inflated again.

The fact that the sculptures are not solid all the way through but filled with air is evident to the viewer through the way in which the works can bend and be manipulated. One work was bent double and tied in place in that position. The wrinkles formed in the material around the ties clearly reveal the works to be inflated, soft and mutable. Despite the organic quality possessed by all the works in the group, they do not come across as living beings. The positions in which the tied-up sculptures are made to stand do not evoke imagery in the viewer’s mind; rather, they exhibit the nature and materiality of the works.

At Kröller-Müller, the six works were set up on low podiums, jointly forming a sequence while at the same time standing on their own.4 In contrast to the first showing of pneumatic sculptures in 1968 at Den Frie Udstilling, the works at Kröller-Müller were largely presented as individual sculptures. At Den Frie Udstilling in 1968, the sheer quantity of sculptures caused them to appear more like a single, unified work, and they were placed directly on the floor rather than elevated on a podium. Indeed, they have primarily been shown without podiums in subsequent exhibitions. The display at Kröller-Müller was more reminiscent of Ørskov’s exhibition at what was then known at Fyns Stifts Kunstmuseum on Funen later in 1968, where the works were arranged inside a marked-out square, as is evident from a single existing photo from the exhibition [Fig. 5]. At Kröller-Müller, the sculptures jointly formed an arrangement that can be described as a tableau vivant. The pneumatic sculptures held their breath, as it were. They stood still, but the stillness became prominently visible precisely because the viewer knows that the current forms of the works are temporary. In the following, I wish to unpack and unfold this particular interplay between stasis and duration and how it creates a special experience of time.

Ørskov was aware of the temporal element in the pneumatic sculptures, and he takes up the theme in texts he wrote about the works. However, I believe that Ørskov’s texts display a tendency towards schematic thinking which can hardly accommodate the full potential of the temporal experience contained within the works. At the same time, Ørskov’s theoretical works have rarely been challenged, and his texts are often used as the primary tool in the analysis of his work. By using the concept of the time-image, I want to call attention to various dualities I believe the works contain. Dualities that facilitate an experience of time as a force of creation and change.

Ørskov: artist and writer

Ørskov’s contribution to the arts was not limited to the production of works; he also wrote a number of books on sculpture. In 1966 he published the book Aflæsninger af objekter og andre essays (Readings of Objects and Other Essays), which collected his texts produced up to then. The year 1972 saw the publication of another collection of texts, Objekterne (The Objects), followed in 1978 by Lighed og identitet (Equality and Identity), and in 1987 came his last book, Den åbne skulptur og udvendighedens æstetik (The Open Sculpture and the Aesthetics of the Exterior).

Despite Ørskov’s prolific output both as an artist and writer, professional reception of his art as well as books has been limited. In 1976, Folke Edward’s aforementioned monograph was published. Beyond this, Ørskov preferred to write about his art himself or to have his wife, art historian Grethe Grathwol, do it. In the various catalogues published in connection with solo shows up to 1990, all but two texts were written by Ørskov himself or Grathwol.5

In 2010, Grathwol wrote the book Liv-stykker og parallelhistorier, hovedperson: Willy Ørskov (Parallel Stories and Pieces of a Life. Main Protagonist: Willy Ørskov), a kind of biography about Ørskov. In 1994, Grathwol arranged an Ørskov retrospective at Sophienholm, accompanied by a catalogue featuring new and older texts alike. In addition, Ørskov is addressed in several reference works, notably by Mikkel Bogh in Dansk skulptur i 125 år (125 Years of Danish Sculpture) and in volume nine of Ny dansk kunsthistorie. Geometri og bevægelse (New Danish Art History. Geometry and Movement), both from 1996, as well as in the anthology Synsvinkler på skulpturen (Views of Sculpture) from 2002. The most recent and most relevant for this article is the exhibition catalogue Bøjninger/Flexions published in connection with Sorø Kunstmuseum’s exhibition of pneumatic sculptures in 2012, featuring texts by Camilla Jalving and Pernille Albrethsen.

In the existing literature, Ørskov is often the primary reference when his art is analysed. The 1994 catalogue from Sophienholm is a case in point: it contains nine brief texts by different authors. All make references to Ørskov’s own texts in one sense or another. Ørskov’s oeuvre is also compared to that of other artists and held up against movements such as minimalism, land art and Arte Povera. However, the starting point remains Ørskov’s own statement and his texts, and no real discussion of Ørskov’s theory is entered into. Differences do exist between the various authors’ texts. Peter Laugesen’s contribution ‘Nullets port’ (‘Gate Zero’) can be said to discuss various deliberations in Ørskov’s writing, while Øivind Nygård’s catalogue text references Ørskov’s own theory to a great extent; for example, concepts from Ørskov’s texts such as ‘syntax’ and ‘objective sculpture’ are used without being explained or queried. A greater distance from Ørskov’s own concepts and theory can be discerned in Bogh’s texts. His article ‘Billedets fysik – Ørskov, tegnene og rummet’ (The Physics of the Image: Ørskov, Signs and Space) in Synsvinkler på skulpturen is probably the only serious existing effort to analyse Ørskov’s theory. Bogh is not necessarily critical of Ørskov’s theory, and indeed he uses it to analyse Ørskov’s commissioned work for Sydskolen in Albertslund. However, Ørskov’s theory does not stand alone here; it is put into context. Bogh defines Ørskov’s theory as phenomenological and centred around the relationship between sculpture and object, forging a kinship with other writing artists such as Donald Judd, Robert Morris and Robert Smithson.6 From the 1960s, Ørskov was preoccupied – as were Judd, Morris and Smithson – with defining a formal concept of sculpture that could accommodate its spatial and temporal extent.

In her article in the catalogue Bøjninger / Flexions, Jalving particularly discusses the performative element in the pneumatic sculptures, while Albrethsen compares them to other contemporary and later artists who also used air.7 In both texts, as in Bogh’s writings, the temporal aspect of the group of works is emphasised. However, it is not the central point in any of the mentioned articles.

Ørskov is, of course, not the only artist to have also expressed themselves in writing. One example would be the aforementioned Judd, who was an art critic before he became a practicing artist. Judd’s 1965 text ‘Specific Objects’ has often been read as a statement of intent for Judd’s own work but was in fact an article Judd wrote at the request of Arts Yearbook, an annual published by Arts Magazine. Judd has since said in a series of interviews that the article was not intended as a manifesto for his own work or for minimalism, but simply an article he wrote because he primarily supported himself as a writer at the time.8 The written word can easily take precedence and become a concrete, specific reading and interpretation of the work. Regardless of whether the artist intended this or not, it completes the work by giving it a meaning outside of itself. The question is, then, what one might see if one disregards Ørskov’s theory and chooses a different lens?

The time-image: The sense of a split now

Time as a theme is naturally embedded in the pneumatic sculptures. They are inflated in order to be exhibited, and while on display they have one form – and may potentially have a different form when they are next exhibited.

To analyse the temporal element in the sculptures I will use the concept of the time-image, which I take from Deleuze’s books on film: Cinema 1, l’Image-Mouvement and Cinema 2, l’Image-Temps. The books divide films in two categories: those informed by the movement-image and those dominated by the time-image. Deleuze argues that in the time-image, time is experienced directly by the viewer of the film, while in the movement-image time is only represented. Historically, the time-image appears, or reaches its full perfection, in films from the 1940s onwards. Some of the earliest films in which Deleuze sees time-images belong to the Italian neo-realism movement, specifically films such as Obsession from 1943 by Luchino Visconti, Umberto D by Vittorio De Sica and Europe ‘51 by Roberto Rossellini, both from 1952.9 Later movements such as the films of the French New Wave are also infused by the image-time. Very simply put, the movement-image film is characterised by realistic action driven forward through the film’s plot. Here, time is represented, often through montage. In the movement-image, montage is used to illustrate the passage of time. In the time-image, the viewer does not experience a realistic representation. Rather, the action or plot is interrupted and derailed. One example would be Luis Buñuel’s 1967 film Belle de Jour, which ends twice with conflicting narratives. In one ending, the main protagonist’s husband is paralysed, while in the other ending he is not – and this is not a matter of one version being written off as a dream or fantasy. In the time-image, various interruptions of plot and action can give rise to images where time is not represented, but presented.10 Deleuze’s books on film and his theory of the time-image are based on the philosopher Henri Bergson’s treatment of time, especially in his book Matière et mémoire from 1896. Bergson’s theory of time can basically be understood as a critique of positivism’s belief in the possibility of a full, perfect mapping of the physical world through various sciences, as expressed by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in Discours sur l’ensemble du positivisme from 1844.11 In Bergson’s eyes, this conviction encompasses a determinism which also possesses an element of something unfree. Bergson argues that time is a factor generally overlooked in philosophy, particularly in positivist thinking. Bergson believes that positivism can be said to spatialise time, which is to say that time is regarded as an object in space. When time is spatialised, the only difference between hour 01 and 02 is quantitative. However, Bergson argues that there is a qualitative difference, given that hour 02 comes after 01. When something repeats itself, it is different precisely because it now involves a repetition. The sequence of events actually contributes to shaping them, as they will be qualitatively different from each other by virtue of their difference in time. Time is a force that is constantly helping to create a new world.12 Thus, the world does not have a fixed form: the constant forward flow of time means that it is always new and different compared to before.

Navigating a world that is always new is not easy. Clearly, we need some kind of structure in order to perceive and experience the world. Spatialised time is an aid, one that is necessary to maintain our experience of self and other entities.13 However, Bergson believes that it is important to also maintain an understanding of the true essence of time. A true understanding of time is a prerequisite for understanding oneself as free, not just as an accumulation of physical material subject to physical laws. Deleuze argues that modern film’s time-images make it possible for the viewer to experience the essence of time.

Deleuze’s theory of the time-image is an elaborate construction of various concepts and image categories which he freely juggles throughout his text.14 In what follows, I will strive to provide a summary of the elements I believe to be pertinent to my analysis.

A central aspect of the time-image is that the film’s action undergoes a slow-down or disruption. The action is interrupted by images to which the film’s characters have no appropriate reaction. To provide an example, Deleuze points to a scene from the film Umberto D in which a young kitchen maid turns on the stove and begins to make coffee. At one point she looks down at herself and sees her pregnant belly, which in Deleuze’s analysis is a sight she cannot acknowledge, comprehend or respond to. The sight of the belly is unbearable. In the scene, we continue to watch the kitchen maid making coffee and getting rid of ants. The sight of the belly is replaced by trivial everyday actions.15 The protagonist of the time-image, in this case the kitchen maid, becomes a viewer on an equal footing with the film’s viewer: the action blurs and becomes ambiguous images. Deleuze links this to Bergson’s theory of perception, in which Bergson argues that perception has action as its goal. Action is possible when an object or situation is familiar. In recognising an object or situation, it is possible for us to act, but this also means that we simultaneously stop observing the object or situation. A surface with four legs is read as a table and provides a number of possibilities for action, but given that the reading (as table) has taken place, the exploration of the object also stops. In the time-image, no aspect of recognition occurs in the protagonist’s perception, and the action stops. Here we arrive at the nub of the time-image, the place where the relationship between the real and the virtual is disturbed, becoming different from normal perception.

For Bergson, the real is defined as the always present, while the virtual is absent. However, the virtual and the real meet through perception and memory. We read objects through virtual images that the real object evokes by way of memory. This merging of the real and the virtual does not take place in the time-image. What happens instead in the time-image is that the real splits, becoming its own virtual mirror image. Thus, the time-image is simultaneously real and virtual, both present and absent. This split and duality in the time-image reflects the nature of the present, which is both present and already past. Deleuze writes: ‘It is clearly necessary for [the present] to pass on for the new present to arrive, and it is clearly necessary for it to pass at the same time as it is present, at the moment it is the present. […] If it was not already past at the same time as present, the present would never pass on.’16 The present is a paradox that cannot be mapped or quantified. The suspension of the contemporaneity of the virtual in the real which occurs in the time-image essentially points to how the present is an entanglement of past and present. The usual state of entanglement is rendered clear, just as it becomes clear how past and present enter into a co-creative but not causal or deterministic relationship.

Can Deleuze’s concept of the time-image be useful for an analysis of Ørskov’s pneumatic sculptures? I believe it can, although it is of course important to keep in mind the differences between the mediums of film and visual art. Specifically, cinema (and literature) have different narrative techniques than visual art. In film and literature, a course of action or sequence of events can be reproduced in a particular order, while the viewer of visual art is presented with the entire product at the same time. However, the main trait of the time-image does not concern the action or plot of the film, but rather individual images or situations. This makes it possible to speak about a certain overlap between the experience of film and visual art. In film, however, the time-image is being experienced by the film’s protagonist first – and then by the film’s viewer by way of that experience. According to Deleuze’s thinking, the time-image means that the viewer of the film is mirrored in its protagonist, who in turn also becomes a passive viewer within the film. No such doubling happens in visual art: here, there is only one the viewer himself. In the experience of visual art, the viewer is comparable to the film’s protagonist.

As mentioned above, Deleuze conceives of the time-image within the context of film history, and it becomes a marker for a particular point in the historical development of cinema. It probably would not make sense to try to use the time-image as a marker for a particular era in art history. Nevertheless, I believe that the time-image can be a useful tool for exploring the temporal experience of the pneumatic sculptures, one which depends on three factors: their lack of associations, the duality between their uninflated and inflated state, and their relationship to architecture.

Pneumatic time-images

As has already been described, the six sculptures at Kröller-Müller were displayed in a manner that evoked associations of a tableau vivant. The sculptures had been inflated for the occasion, unlike other works in the exhibition, which were simply placed in the halls without any change in their state or appearance.

In the viewer’s encounter with the pneumatic sculptures, a silence arises. Being simple, hollow casings, they do not hide anything that the viewer can discover by looking at them for longer. In his Ørskov biography, Edwards cannot think of anything to say about the works other than to call them an anomaly within Ørskov’s overall oeuvre. In his text in Dansk skulptur i 125 år, Bogh describes Ørskov’s work as constituting a ‘point zero’ where the starting point of the sculpture is zero or a silent point without any references to anything outside itself.17 However, this is not necessarily unique to the pneumatic sculptures, but could be said of much abstract art. Even so, it can be argued that the point applies more to works such as the pneumatic sculptures than to, for example, abstract expressive painting. In expressive painting, the subject matter is indeed abstract and as such without an object, but it can be read as a direct result and impression of the artist’s movements, as in the case of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. The work can be read as the relevant artist’s modes of expression, which gives the work an object outside of itself.18 The pneumatic sculptures also bear imprints of the hands that made them. For example, the work in the Kröller-Müller’s collection which was doubled up and tied for display has several stains presumably originating from the glue used to put the work together. The ties that hold the work can also be said to point back to the work’s creator, yet neither the stains nor ties found in the pneumatic sculptures are sufficiently expressive to act as the artist’s voice or reflect an artistic temperament. The stains and ties remain part of the work’s own sphere; they do not establish a connection between the viewer and the creator behind it. At most we see a glimpse of how the creator carried out the practical design of the works. The viewer is left alone with the work. As Birgitte Kirkhoff Eriksen and Charlotte Sabroe say about the group of works in the preface to the exhibition catalogue Bøjninger/Flexions from 2012: ‘It does not look like anything, or, to put it in a slightly different way, it looks like nothing we recognise. It does not express the artist’s subconscious, nor is it a symbol of something greater than itself. It is free. It just is.’19

In the above I have described the pneumatic works as poor in associations, a point which can be elaborated upon. They do in fact evoke associations, but those associations never reach the finish line. The black piece at Kröller-Müller can be said to form a gate with its two legs, yet no real connection between the work and the image of a gate occurs. The unpainted work, which is only half-filled with air, has proportions that make it reminiscent of an enlarged and broken cigarette, but in this case too it is not a perfect match. Seen through the lens of Deleuze’s thinking, the non-possible association and the objectless work can be described as the starting point for the time-image, the point where the current moment cannot be recognised through virtual images, causing the action to stop. There is of course a difference between what action means in film and in the perception of art. Within the cinematic time-image, the thing that stops is the characters’ appropriate or realistic reaction to what they experience or perceive. That is, the film’s plot comes to a standstill. The experience of art is of course different. The viewers do not act in the same way in their perception of art. However, most people will, in their encounter with art, seek to categorise the work and provide it with a context that contributes to a meaningful interpretation of the work. It is this act of interpretation that I believe is challenged in the encounter with the pneumatic sculptures.

In time-image films, the incomplete chase between the real and the virtual becomes fertile soil for a splitting or doubling of the real. Specifically, this can manifest as reflections, meaning images where the film’s protagonist sees themselves in a mirror, causing a doubling. This does not happen in the experience of the pneumatic sculptures, but in turn they contain a doubling in themselves. On display and inflated, they constantly remind the viewer of their opposite, non-inflated state. This applies to all the works, but it becomes particularly striking in the painted works shown at Kröller-Müller, as the cracking paint clearly indicates that these pieces are usually kept flat and packed up. What are they when they are not inflated? Are they still sculptures then, or only potential sculptures? Do they exist all the time, or only when they perform their tableau vivant? In time-images on film, doublings and reflections confuse the relationship between the film’s protagonist and the actor who plays the role. Things become unclear: what is a mirroring and what is not? In the pneumatic sculptures, a similar duality can be discerned. A duality that is paradoxical and impossible to resolve: the works are sculptures in their inflated as well as in their flat state – and yet not. What is their true state: inflated or flat? In Deleuze’s thinking, the film’s reflections and doublings become images that point to the paradoxical duality of the here and now being both present and already past. Contending that the duality of the pneumatic sculptures gives the viewer insight into the duality of the present is perhaps belabouring the point. However, I do believe that one may argue that the duality inherent in their expression can be fertile ground for a particular perception of time in which the works possess presence, yet at the same time cannot be maintained in their present state. Bogh says about the sculptures:

For Ørskov, the pneumatic sculptures […] had the advantage of being made out of a nondescript material without too many layers of meaning, and, more importantly, of being forms that exist for a limited period of time only, meaning until the air is let out of them. This timed aspect, this pre-arranged and expected disruption of the sculpture augments the work’s current presence in the room.’20

As Bogh emphasises here, the works possess presence because of their temporality. Jalving’s text discusses whether the works mimic persons or people and ends up arguing that the works have the presence of a person without representing the human figure.21 I, on the other hand, believe that the presence possessed by the works is specifically rooted in their lack of reference to any external object or motif. As Bogh mentions, there is little handed-down significance in the material used to create them, and while their form is organic, it does not depict anything. Given that the work has no object, it is difficult to insert into a meaning-making chain of signs and signifieds. This also makes it difficult to keep the work firmly fixed in one’s memory. The objectless easily slips from our memory, despite the fact that it feels very present at the moment. This contradictory sense of a presence that cannot be firmly grasped and retained makes for a different experience of time because memory is part of that experience, one which allows the present to pass and become the past. When memory cannot be retained, or the present cannot be recognised by accessing our memory, it is as if the present does not pass. This makes for an experience of an open-ended ‘now’ suffused by a high degree of presence, one that simultaneously prompts a sense of rudderless lack of direction.

The presentation of pneumatic sculptures at Kröller-Müller was reminiscent of how they were exhibited at Fyns Stifts Kunstmuseum in 1968, where they were also placed more or less separately and isolated from each other. In most other exhibitions for which documentation exists, the works have been shown in a more installation-like manner. After the first couple of exhibitions, Ørskov began to create larger works that occupy the space in different ways than the smaller ones. At Ørskov’s exhibition at the Jysk Kunstgalleri in Copenhagen in 1969, he showed three large works that can be described as double bridges in which a large bridge is supported by a smaller one in the middle [Fig. 6]. Together, the three pieces created their own architectural structure in the exhibition. At his second exhibition at Art and Project in Amsterdam in 1971, Ørskov also showed very large works that entered into a direct conversation with architecture [Fig. 7]. In the same way as the smaller ones, the large works have a temporal, durational aspect that is clear to the viewer. When they interact with architecture, their temporality rubs off on the setting. To us as observers, the works make us aware that the so-called fixed architecture also has a temporality, even if its horizon is different from that of the sculptures.

In 1979, Ørskov presented an exhibition at the Glyptoteket in Copenhagen, consisting primarily of pneumatic sculptures [Fig. 8]. The few existing photos from the exhibition clearly reveal that Ørskov took an installation-like approach. A large bridge cuts across the room, and rather than standing as individual sculptures, the sculptures jointly create a whole. The pictures show a work which forms a bridge, but with two knots in it. Another work stands at an angle with one end leaning against the wall and the other tipping over, not fully inflated. The works showcase different possible formations, and as viewers we are invited to co-create and take the ideas further, even if this co-creation must take place purely in the imagination. The observer feels an urge to create new formations, move them around and test how far the works can be manipulated. All this creates a space that accommodates continuous change and remains open-ended. On the one hand, the changeability of the installation contrasts with the fixed firmness of the architecture, but at the same time it also instils a greater openness into the architecture, a sense of something playful.

In his book on the time-image, Deleuze repeatedly touches upon the spatiality that he believes arises in films where time-images occur. Just as the film’s action is slowed down in the time-image, so does the time-image disrupt the film’s spatial continuity. One of the films to which Deleuze returns several times throughout his book is Last Year in Marienbad from 1961 directed by Alain Resnais. In the film, a castle converted into a spa hotel forms the setting for a story in which very little is particularly clear, including the relationship between a man and a woman. The castle as a location also remains unclear. It does not feel like a real place, but rather as a structure that is constantly being put together anew. Just as the time-image protagonist is mirrored and split between character and actor, so the time-image space is also divided between being scenery and places that seem real and coherent.

Shown in the Glyptoteket halls designed by Danish architect Vilhelm Dahlerup, the pneumatic sculptures can also prompt an ambiguous, spatial experience. The hall’s architecture is richly decorated with pictorial friezes and painted ceilings to imposing effect. As an observer, you have ample opportunity to reaffirm your own education and sophistication by reading and identifying various historical references and classic narratives. Seen up against architecture so heavily laden with meaning, the pneumatic sculptures come across as lightweights by comparison. On the other hand, the sculptures’ playfulness and clear temporality expose the setting’s self-importance and its desire to appear eternal and timeless. At the same time, the pneumatic sculptures also engage in a conversation with the room’s original colourfulness and tactile diversity. The sculptures can be seen as a contrast to the architecture, but they can equally be said to accentuate an eclectic element in the architecture. On the one hand, the pneumatic sculptures empty the architecture of meaning, and on the other hand they can be said to breathe life into the monumental space. The works create a space that incorporates different temporal durations and alternates between being alien and open – being a backdrop in the sense of being false and a backdrop in the sense of being temporary and thus in a constant flux. This duality also gives rise to a certain perception of time. If the temporality of the pneumatic sculptures can be said to transmit itself to the architecture and highlight its own sense of duration, that same temporality also transmits itself to the viewer. And with that temporality comes a split.

I believe that the concept of the time-image articulates a split in the current moment which is useful for describing the viewer’s temporal experience of the pneumatic sculptures. Their association-poor or objectless nature puts a stop to their interpretation. It gives them a high degree of presence, which, however, is difficult for the viewer to grasp and sustain. Their dual identity, suspended between inflated/flat, sculpture/non-sculpture, has a temporal aspect that rubs off on their surroundings and the viewer alike.

Ørskov without Ørskov

Ørskov’s theory is often used to analyse his own works. I have chosen here to eschew Ørskov’s own reading in favour of a different angle. By distancing oneself from Ørskov’s own statement, it becomes possible to contribute something new rather than simply repeat the usual reading. In what follows, I will look at where my interpretation of the pneumatic sculptures resembles and differs from various parts of Ørskov’s writing. My focus is on how the temporal experience of the pneumatic works can be expanded by applying other theories, which, however, also involves a reassessment of the general relationship between work and text, as well as of whether Ørskov’s writings should be considered a single, unified whole.

Overall, Ørskov’s texts can be seen as an attempt at articulating a phenomenological theory of sculpture. For Ørskov, art is a space where we humans can approach reality and achieve a truer understanding of the world.22 There are several places in Ørskov’s texts where his own reading of the pneumatic sculptures and their temporality agree with the reading I have presented using the time-image as a central concept.

In the text ‘Metaobjektet’ (The Meta-Object), Ørskov analyses an example of a pneumatic sculpture. Here he not only relates to the inflated form of the work; he also includes the non-inflated state as part of the sculpture. He describes the uninflated sculpture as an un-activated casing holding a number of possibilities, an object with potential. Ørskov explores this further when, later in the text, he describes the inflated sculpture as a meta-object: ‘As far as the depicted sculpture object is concerned, it conveys to the viewer a sense of the object as such and provides further insight into communication with the object world. It is a kind of image of an object – a meta-object.’23

To Ørskov’s way of thinking, the pneumatic sculpture is also an objectless object, one which ends up containing its own mirroring or splitting:

The modest illusion perpetrated by the depicted sculpture is to pretend to be an object (objective reality) and yet only be an image of an object – (insofar as it is a work of art) – object-depicting, meta-object. It exists on the artistic level. – But at the same time, of course, it exists on an objective level of reality, it is an object, – that is, an object which pretends to be a work of art, a sculpture. These two figures mutually mirror each other: the object which pretends to be a work of art and the work of art which pretends to be an object. It is like a photographic double exposure where large parts of the two figures overlap and cover each other, are each other.24

The duality in the sculpture described here by Ørskov can be meaningfully combined with my interpretation of the time-image in which the real doubles itself because there is no aspect of recognition to give the perceived an external object. In Ørskov’s thinking, however, the duality in the work is not directly linked to the experience of temporality. To Ørskov’s mind, the theme of time finds direct expression as the pneumatic sculptures are processual and changeable. The duality he describes in the quote above is not linked to a temporal experience. If we turn to the time-image for perspective, the work’s duality as object/sculpture is tied to the temporal: the doubling that takes place can be compared to the doubling or splitting that occurs in the time-image. The doubling reflects – or equals – the duality of the present, which is both present and past at the same time.

Ørskov’s writing also includes concepts which point in the opposite direction and do not align with the reading of the pneumatic pieces as time-images. In the text ‘Skulpturens syntaks’ (The Syntax of Sculpture) in Aflæsning af objekter (Reading Objects), Ørskov articulates what he calls a working hypothesis aimed at creating a so-called maximal sculpture. The text is from 1965, meaning that it predates Ørskov’s pneumatic sculptures and is thus not specifically about that group of works. The text contains no references to Ørskov’s own work and so offers no specific examples of what a maximal sculpture might look like. By maximal sculpture, Ørskov means a sculpture that has ‘great range, great precision, great directness; in other words, the sculpture becomes an effective instrument.’25 According to Ørskov, this can be achieved through a clear sculptural syntax, which means that the parts of the sculpture relate clearly to each other. A well-defined syntax creates a clearly legible sculpture. This requires a high degree of precision in the sculpture. With the right precision, art can function as an instrument:

Art is an instrument for capturing reality. With its help, we can determine our relationship with the environment; indeed, we can establish it. This is the one side of art. But art is also an instrument of choice. That choice is an assessment. This is the other side of art, the ethical one. We must leave the choice, the ethical side of art, to each individual. What we can discuss, and must discuss, is the establishment of the relationship with reality: 1) the objectification, and 2) the development of the instrument.26

Here, Ørskov adopts a logical-analytical approach to art and voices a belief that it is possible to map this field through analysis of its individual parts. Parts which, according to Ørskov, can be separated from each other. With this move, what he calls the ethical side and the objective side are separated as two parts that have no influence on each other. However, Ørskov does not see the artwork as entirely autonomous and free-floating: in the text he states that every work must be seen in relation to its reference system, which can be an artistic tradition. Ørskov expresses a belief that this reference system can be mapped: ‘The reference system must be clearly documented; for it is through this that the observer gains entry into the new image.’27 According to Ørskov, creating a maximal sculpture is made possible through precision, clear syntax and a documented reference system that also makes the work universal: ‘Only a universal culture can be worth working with or for.’28

Writing about Ørskov and his theory of sculptural syntax, Bogh says: ‘Ørskov was well aware that such a thing as a completely logical sculpture must, in addition to being a utopian notion, necessarily be a sculpture devoid of poetry.’29 In a way, it is logical to think that Ørskov saw the notion of a maximal sculpture as a purely theoretical idea that could not be realised. The problem is that he does not say so in his writing. The idea of a maximal sculpture does not necessarily come to the fore in his execution of works. Ørskov kept developing new groups of works in different materials and with very different modes of expression. He never found a basic form with which he could persistently and continuously work and thus unfold the idea of a sculptural syntax. In his texts, however, he does seek for something more systematic, which occasionally leads him towards a universal and deterministic way of thinking.

When applying the time-image as a lens for examining Ørskov’s idea of a universal and maximal sculpture, a number of questions are raised. In Deleuze’s conception of the time-image, the objective is for the viewer to be presented directly with time, which according to Bergson’s theory is a force that constantly creates the world anew. Using the time-image as a starting point, it follows that trying to map a complete sculptural syntax would be an illusion. Speaking about a sculptural syntax and a reference system that can be charted is, in Bergson’s view, a way of thinking that spatialises time and in which the mutating power of time is overlooked.

Seen up against the idea of a maximal sculpture and sculptural syntax, the pneumatic sculptures seem too unstable to be able to achieve this. As sculptures, they are reduced in terms of expression, but this reduction has not yielded stable sculptural foundations. Rather, the result is a playful sculpture that is difficult to firmly grasp. These are not sculptures that can help define a fixed syntactic sculptural system. Instead, they tend more towards forming an open-ended, ever-changing totality. Their transmutation and openness reflects the change that is constantly ongoing in the flow of time.

I believe that Ørskov’s work deserves to be read through lenses other than Ørskov’s own theory. Taking one’s point of departure in other theories, it is possible to see the sculptures as well as Ørskov’s thinking through fresh eyes. Ørskov’s texts tend to be studded with diagrams and generally strike a universal tone, creating the impression that his texts are intended to constitute a fully formed overall theory of sculpture. However, it may be better to understand his writing as a collection of essays that are allowed to go in different directions. When seen as essays rather than as a single, fully-fledged Theory of Sculpture, his writings are not necessarily the obvious and inescapable starting point for an analysis of his work. Possibly the urge to interpret Ørskov’s work through Ørskov’s texts is also connected to a desire to find an object for the otherwise silent sculptures. When the pneumatic sculptures come across as silent and devoid of expressiveness, the artist’s text offers itself up to act as his voice and as the object of the work. Then, the pneumatic sculptures are not allowed to remain open-ended and unstable. They are stabilised and propped up, with Ørskov’s theory acting as a supporting framework. However, I believe that in the experience of the pneumatic sculptures, the sensation of instability and openness is precisely the one aspect that pokes and prods the viewer into awareness – into a probing, tingling experience of temporality.