Summary

Danish artist Kristian Zahrtmann (1843–1917) painted pictures that today seem obviously queer. The article finds traces of a contemporary reception which, without saying it directly, recognised the nature of his project. In his late paintings, the artist deliberately works with creating a fusion of his person, his work and his home. That project is presented as an effort to create a space of one’s own, forging an opportunity to live a queer life under adverse circumstances. The article also sets out a framework for a group of new international research articles examining Zahrtmann in the light of queer theory.

Articles

What follows will take its point of departure in a single event picked from the life of Danish artist Kristian Zahrtmann – his seventieth birthday – using it as a springboard for discussion what may well be Denmark’s queerest artist from the past. Metaphorically speaking, the objective is to climb up the mountain of writings, opinions and interpretations about Kristian Zahrtmann in order to delimit a specific, local point of view – a new ‘perspective’ on one of the most important and still sadly overlooked projects in Danish art history. As such, this is a research article that draws on existing and familiar material1 – albeit set within a new framework of interpretation – supplemented by new sources. The article also serves as the background of an exhibition at three Danish museums in 2019 and 2020, where it will constitute the first among an entire collection of articles interpreting Kristian Zahrtmann in terms of queer aspects and queer theory. A central theme of the article is the idea that Zahrtmann deliberately interweaves life and art into one another in his quest to create his own place, a concept which here includes a concrete, tangible space and a general opportunity for self-expression. I have chosen the term ‘home-stead’, combining terms for ‘home’ and ‘place’, to convey this sense of searching for a place of one’s own. But let’s not dwell too much on methodology here at the outset – our journey begins with birthday celebrations without the man of the hour present, and some questions about place and presence prompted by this fact.

The missing birthday boy

‘Kr. Zahrtmann’s 70th birthday has been celebrated today – in articles, poems, letters and telegrams. But the festivities have taken place with no birthday boy in sight. Where is Zahrtmann?’ writes ‘Niels Griffel’ in Danish newspaper Ekstra Bladet on 31 March 1913. He is quick to quote the reply given by the housekeeper when the journalist knocks at Zahrtmann’s door in his search: ‘Today, Mr Zahrtmann is nowhere’.

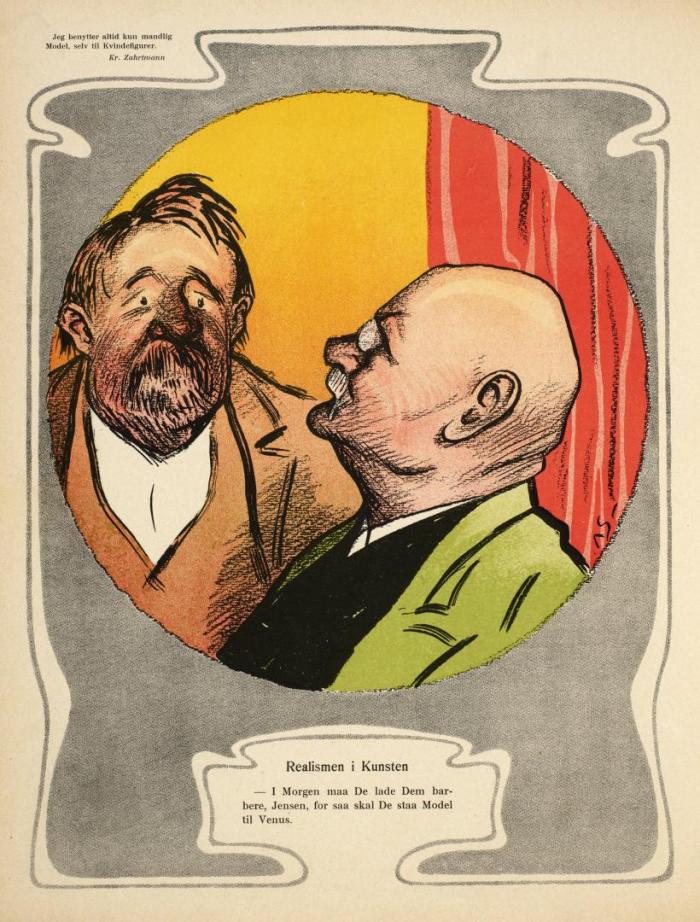

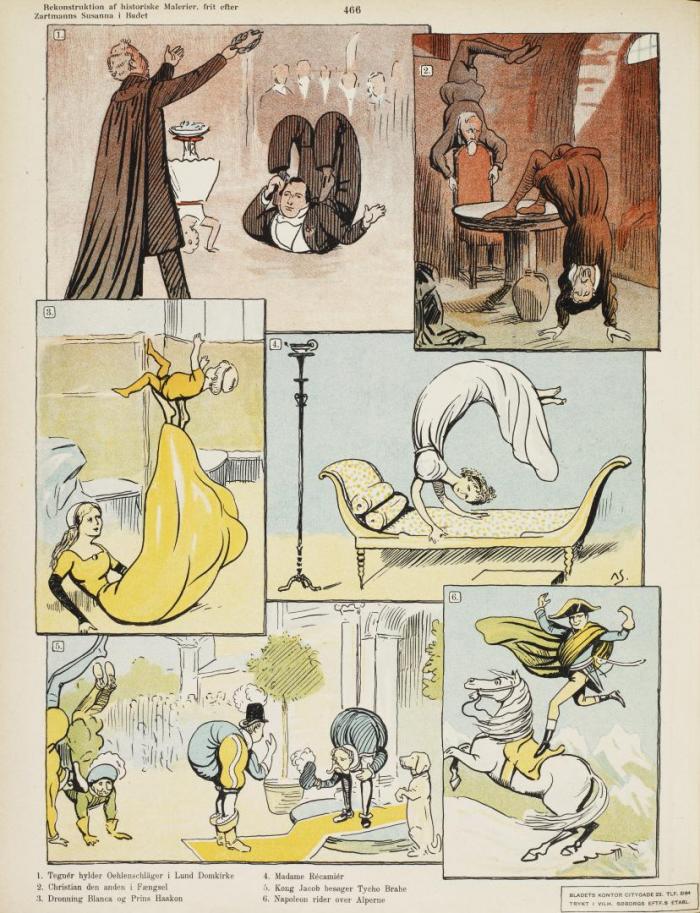

But Zahrtmann is certainly demonstrably present in newspapers and magazines. Portraits and articles first began to make an appearance in the days leading up to his birthday, outlining a portrait of the artist which would, with only a few contentious voices being raised, remain in force for a hundred years to come [fig.1-2]. In 1913, Kristian Zahrtmann is particularly noted for his role as a teacher at Kunstnernes Studieskoler from 1885 to 1908, where his department was known as Zahrtmann’s School,2 and for the crucial impact he has had on several generations of Swedish and especially Norwegian and Danish artists through his twenty-four years of teaching in opposition to the very traditional style of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. His many pupils include the so-called Funen Painters, Johannes Larsen, Fritz Syberg, Peter Hansen, and – even though these were as-yet unremarked on by critics in 1913 – future Modernists such as Edward Weie and Harald Giersing. Around the time of his 1913 birthday, newspapers and magazines also wrote about Zahrtmann’s crucial support for the establishment of Den frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition) in 1891, the first permanent exhibition society to oppose the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and its juried salons. From a present-day perspective, we see the foundation of Den frie Udstilling as a necessary new addition to the art institution in Denmark, and one which was instrumental in enabling a number of new art movements and -isms to assert themselves in Denmark. Many articles and features make a point out of relating how well-liked Zahrtmann is as a person, but also that his art only truly won recognition during the 1890s, even though he had actively exhibited his work since 1869, including at the annual academy-arranged juried spring salons at Charlottenborg.

Newspapers and magazines provide lavish accounts of his annual trips, accompanied by various friends and students, to Italy and the small Italian town of Civita d’Antino in Abruzzo east of Rome, where they particularly highlight his warmly affectionate relationship with the town’s inhabitants. Zahrtmann’s ‘Italian’ everyday scenes, full of sun and laughter, receive particular praise, and the master himself is allowed to take the floor, presenting a small piece on his recollections of ‘A day in Civita d’Antino’ in Illustreret Tidende.3

Yet another aspect attracted attention: Zahrtmann’s special affinity with the figure of Leonora Christina (1621–98) [fig.3-4]. She was a Danish princess who ended up imprisoned for many years in Copenhagen Castle, and as a historical figure she won newfound popularity due to Zahrtmann’s many paintings interpreting her life and times; a fascination which continued up through the twentieth century and to our present day, where Zahrtmann’s paintings continue to shape many people’s perception of Leonora Christina.4 By 1913, the link between Zahrtmann and the royal prisoner had been firmly established, but it also points back to some of the first major written treatments of Zahrtmann’s work,5 for example, the connection is reiterated and reaffirmed on the occasion of Zahrtmann’s sixtieth birthday in 1903 and his retrospective in 1907.6 In every version of the narrative about ‘Zahrtmann and Leonora’, his first reading of the royal scion’s Jammers Minde (Memoirs of my Wretchedness) in 1869 is seen as a decisive leap within his oeuvre,7 and his first paintings of Leonora Christina in prison are regarded as a definite break with the past. The editor of Illustreret Tidende, Helmer Lind, expresses the general view: ‘Immediately upon their arrival they struck one as something alien, almost a rebellion’. Lind particularly points out that these paintings are devoid of all traditional, bourgeois aesthetics or sentimentality. These are new images, cultivating a different kind of steadfast resolve. And the result is a new kind of art: ‘This particular historical figure is not alone in being seen in a different way than before; Eleonora Christina, as Zahrtmann has recreated her, has taught us to read history in general through other eyes than before, on a larger scale, richer and bolder’.8

A mentor and catalyst for young painters and new art institutions, and the one artist to breathe new life into history painting by giving it psychological depth – there is widespread agreement on the main outlines of how the story of Zahrtmann should be told and on the place he merits in art history. ‘He lets us see, – as the most brilliant of history writers can – with one glance, far more than what may be learned through many a laborious hour of reading’.9 In this sense, the celebrations surrounding Zahrtmann’s birthday also become a nexus that brings together all the narratives about the ageing artist while reaffirming his prominent position on the Danish cultural scene. Overall, this image has remained in force up until the present day. And yet, the ritual praises expected of any anniversary celebration is also mingled with quite a lot of hesitation and uncertainty about the artistic project. Words such as ‘strange’ (sær),10 ”‘peculiar’(ejendommelig)11 and ‘bizarre’ (mærkelig)12 are bandied about prolifically about the artist and his art – and not for the first time. Several express reservations about the quality of his later production, certain subjects are judged to be grotesque, and the artist – who couldn’t possibly be serious, could he? – is often seen as a wit or satirist. The concept of ‘paradox’ is quite central when newspapers are called upon to describe Kristian Zahrtmann’s art.

The journalist from Ekstra Bladet quite literally searched in vain for the artist. But in fact, the dual experience of ‘finding’ Zahrtmann – by which I also mean identifying a specific narrative about his achievements and results – and yet not finding him at all, or at least finding something paradoxical – is in fact quite symptomatic for the general view of Zahrtmann during his own day. It is my contention, and a key point underpinning this article, that Zahrtmann himself was aware of how difficult it could be for him to find a place – and to play a role – that was unequivocally his, yet also acceptable in the eyes of his surroundings. During the last two decades of his life, his efforts appear to bear fruit, but not without continued challenges.

The character of the artist

Where, then, might one find Zahrtmann in March of 1913? Many guessed him to be in Civita d’Antino, but in fact the artist was staying incognito in Lucca, quite happy with not being sought out and possibly ill at ease with the idea of having to live up to his public persona in all the brouhaha surrounding his birthday. Irrespective of his absence, however, the celebrations of his seventieth birthday serve to reaffirm a particular narrative about Kristian Zahrtmann, making this a key nexus of his career. As such, it is excellently suited to showcase the artist’s widely proliferating network.

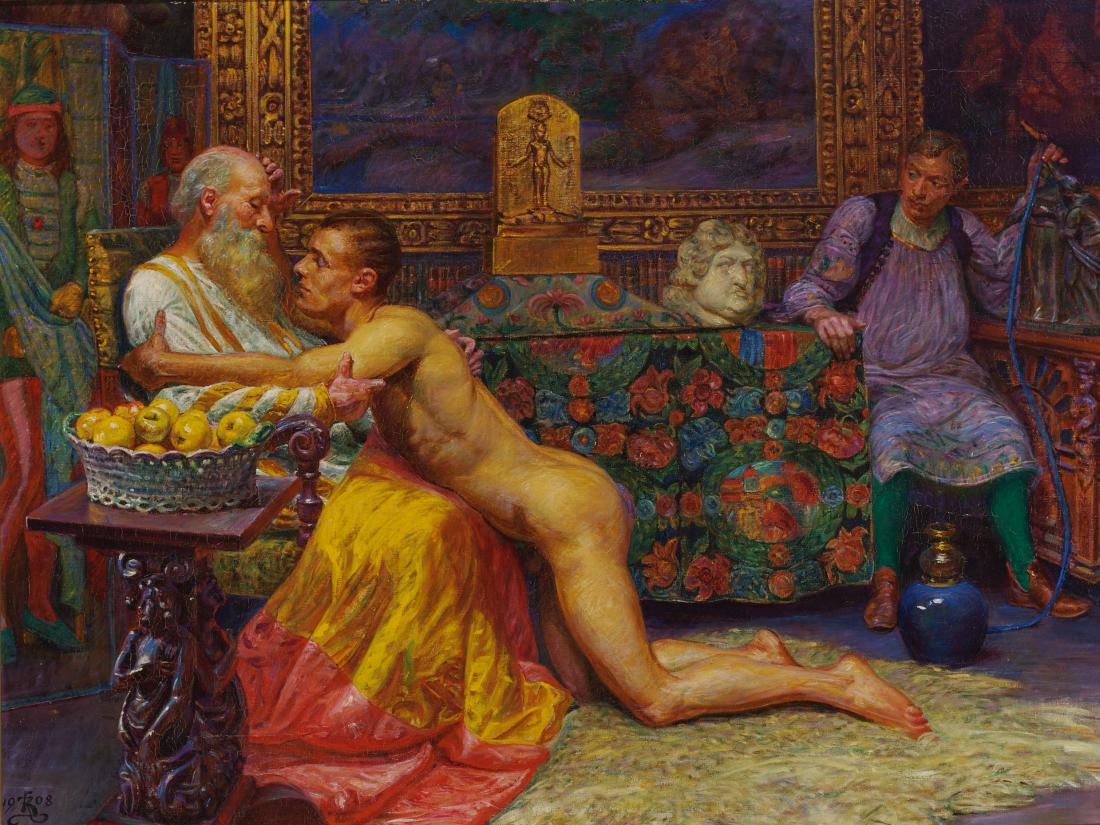

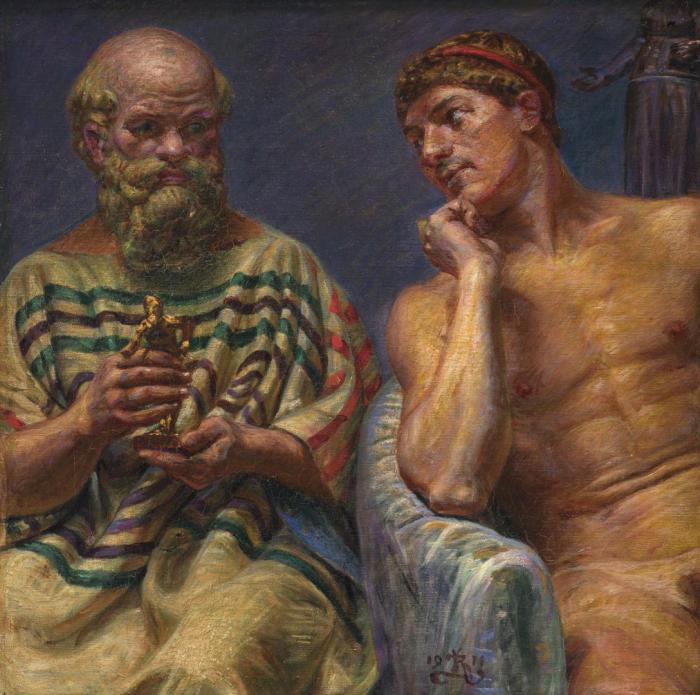

If, however, we turn to Zahrtmann’s more general status around the time of World War I, his network of allies cannot wholly safeguard him against all resistance. In the more brusque realm of reviews, Zahrtmann is often the target of harsh responses. A typical review from 1914, the year after his seventieth birthday, writes disparagingly of a ‘cacophony’ in the colours of his paintings, and of ‘[…] startling contrasts within the same painter’s production […]’.13 The next year, in 1915, the influential art historian Vilhelm Wanscher launches a fierce discussion in newspapers by baldly stating that ‘[Zahrtmann] is in contravention of good taste’ and, accordingly, ought to down tools; a critique which is about artistic style, but also and perhaps especially about the choice of suitable – or inappropriate – subject matter: Zahrtmann is directly advised to refrain from ‘[…] painting these statuesque male models between fronds of palms against glowing sunsets’.14 Seen in conjunction with the aforementioned review, which criticises Zahrtmann’s depiction of ‘Socrates as an ancient lecherous fool and Alcibiades as the vilest, most vulgar modern wrestler imaginable’,15 the discomfort surrounding the artist’s choice of archetypal homoerotic subject matter becomes clearer. More on this later.

Mostly, however, the discussion surrounding Zahrtmann and his art is carried out with tentative caution, presenting its critique obliquely. His choice of subject matter often attracts discussion, as does his use of contrasting colours. The influential art historian and museum director Emil Hannover uses the seventieth birthday as an opportunity to describe the best uses of colour in Zahrtmann’s painting, stating that ‘a slight discordant note is added to their harmonies’, while others use the more positive term ‘symphony’ to describe a use of colour which contrasts cool up against warm.16 Bold and intense colours that do not comply with the dominant naturalistic tradition remain a typical trait of Zahrtmann’s art throughout, and critics often reach for metaphors from the realm of music when describing the distinctive effects.

In everything that is written about Zahrtmann – in the birthday accolades and in reviews and critiques before and after the event – questions about personality and character hold a central position. Critics and commentators commingle Zahrtmann the man with Zahrtmann’s work, and adopting a position on one means adopting a similar position on the other. The term ‘character’ is often applied, serving a dual meaning: it points to the strong idiosyncratic personality of the paintings and the strongly positive and unique personality of the artist; at one turn Zahrtmann himself is described as ‘manly’, then the figure of Leonora Christina in his paintings is described as possessing ‘poise and power, dignity and nobility’.17 Many years later, art historian Erik Mortensen has commented on how art criticism around 1900 would repeatedly highlight ‘the crucial importance of personality’, even if that self-same criticism often had trouble with the truly original personalities such as Hammershøi, Willumsen – and Zahrtmann.18

As regards the question of character, we see that around this time, the issue is more about the critic than about the art – it centres on how the reviewer sees himself mirrored in the art. Supposedly, the artist and his art are being judged, but in actual fact the art and artist are compared up against the critic’s own character – do they match his standards and strength of character?19 And in the case of Zahrtmann’s birthday, this leads to many instances of judgments which very directly impose the critic’s personal values on the entire matter without further argument. Such assessments often seem out of step with the art it is all about, devoid of sensibility to the man being celebrated: ergo, Zahrtmann and his art may seem as hard as granite in one critic’s eye, but sensitive and empathetic in the eyes of another. ‘But, who knows Zahrtmann! Any description of him will be incomplete because the opposite will be just as true’,20 says Ernst Goldschmidt in a birthday greeting that appears to comment on the many different gazes on Zahrtmann and their difficulties in pinning down the man and his art in a consistent assessment.

The ‘paradoxes’ perceived in Zahrtmann’s work say something important about the established expectations about consistency and uniformity in an artistic oeuvre: critics of the age believed it should be possible to grasp the work and artistic persona from the viewer’s personal morals and values, rather than by empathising with the worlds evoked in the works or by seeing them as comments on contemporary culture. My argument – seen from a very different viewpoint here in the twenty-first century – is that Zahrtmann’s work seeks to add side stories alluding to alternative ways of living out one’s sexuality and gender; it seeks to create a hitherto absent place or room in which other stories can be played out. In the eyes of the critique prevalent of the time, which cultivated a narrow starting point in the world of the viewer-reviewer, such side stories might seem strange and difficult to grasp because reflection began and ended with sheer ‘gut feelings’. As a result, much was overlooked in disinterested silence, whereas Zahrtmann’s allusions and secondary narratives seem considerably more accessible today. I shall return to the reception of Zahrtmann’s subversive narratives in a little while; for now, it is time for some reflection on Kristian Zahrtmann’s late and very queer work as statement and expression.

Queer Zahrtmann

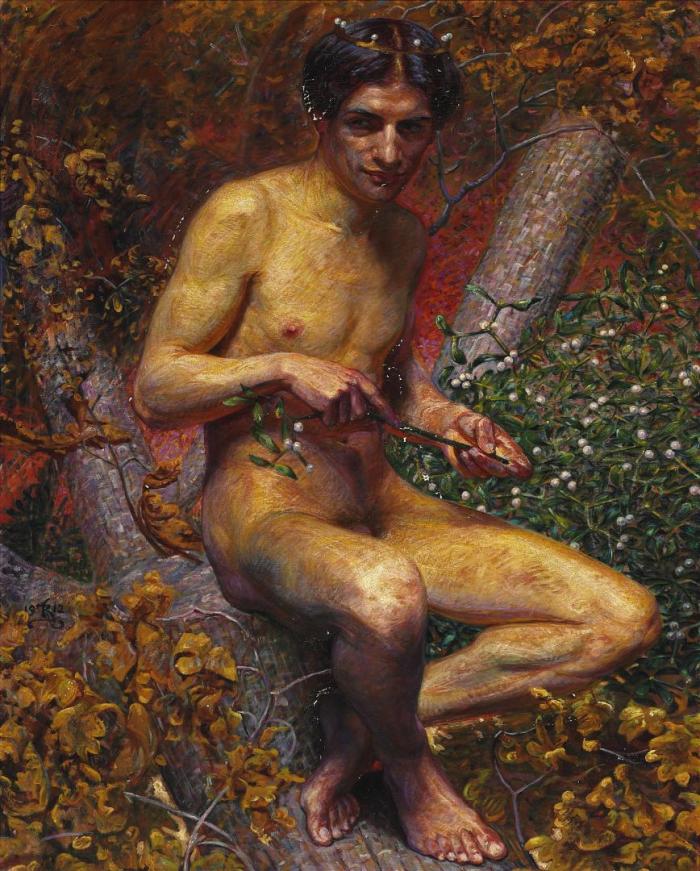

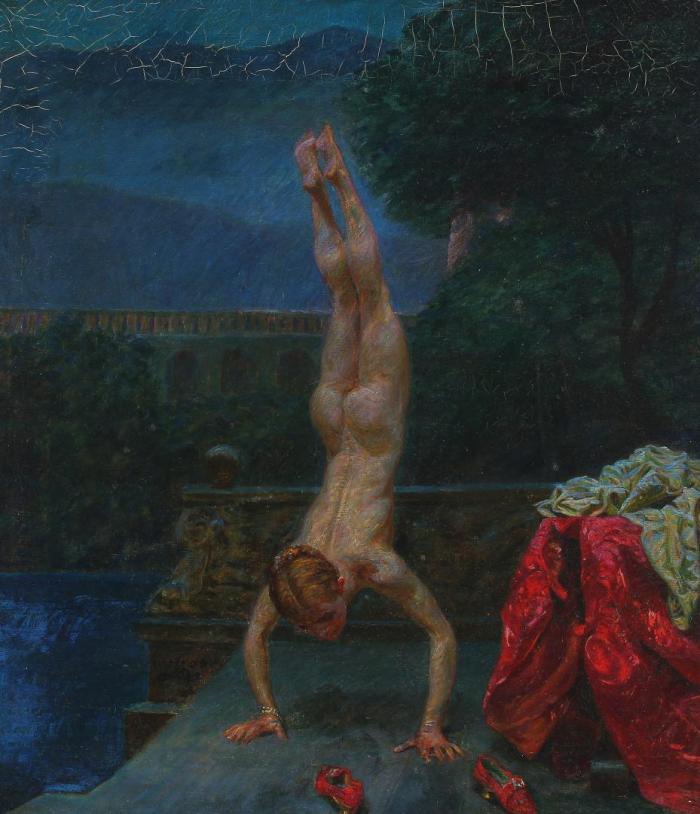

By the anniversary year of 1913, Zahrtmann had already painted and exhibited a number of works where hints and allusions were growing more overtly homoerotic. The display of Prometheus [fig.5] at Den frie Udstilling in 1904 can be regarded as an intentional turning point – signalling a change of direction to those in the know – outlining a new, more obviously queer direction in Zahrtmann’s art in public. The work itself quite deliberately builds on a well-known, mythological motif that lends itself well to being inserted into various situations; for example, the exuberant reception of artist Carl Bloch’s version from 1865 saw the chained Prometheus as an allegory of Denmark’s loss of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.21 Like almost all of Zahrtmann’s queer works, his take on the theme also seeks some kind of shelter under the shield of tradition – its aegis22 – in order to carry out a deliberate processing and updating of tradition, a kind of twisting or queering of something pre-existing: Here is my version. In contrast to Bloch’s very well-known painting, Zahrtmann’s version does not have a dramatic, resolved narrative. Instead, his Prometheus draws on centuries of depictions of passively lounging, sensual female bodies, using a veneer of mythological respectability to invite a gaze full of desire and pleasure.23 In the hands of Zahrtmann, Prometheus becomes an erotic narrative. Given that the nature and character of the artist himself is so central to the assessments of art made around this time, Zahrtmann himself becomes a framework through which his 1904 Prometheus can also be understood: the position assigned to the observer becomes homoerotic because it is implicitly the point of view of another man, and because the narrative and mythological aspects fall away. The suffering one senses might potentially be inflicted by the vast eagle, the overemphasised chains and the hard rocks only serve to heighten the titillating effect of the painting and its ‘dangerous’ hints of sadomasochist dominance.

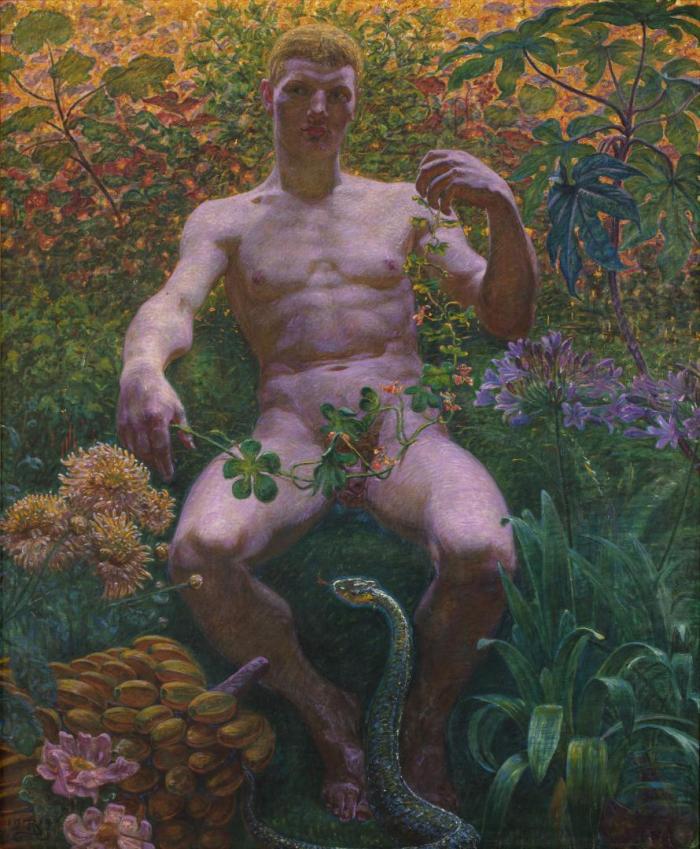

Exhibition history should be recognised as a key aspect of the overall effect and impact of Zahrtmann’s art. It would appear that Prometheus is exhibited at a propitious time – Zahrtmann is highly acclaimed, financially secure and firmly embedded in many networks24– and upon being presented at Den frie Udstilling in the spring of 1904, the work stands out among a range of the artist’s less important Italian scenes.25 This is to say that the artist mobilises his considerable public esteem to promote a painting that might be controversial, not least because it also affects the general perception of the rest of his art: being familiar with Prometheus or subsequent erotic works such as Loki from 1912 [fig.6] and Adam from 1914 [fig.7] has a reverse knock-on effect: knowing about these works, all of Zahrtmann’s preceding oeuvre can at any time be seen as latently other than what it appears – as queer.

For these purposes, I regard the term ‘queer’ as more than simply another word for ‘homosexuality’ and homosexual desire. Queer is also a verb, an act – to queer. ‘[…] queer can be used as a verb, that is, to describe a process, a movement between viewer, text, and world, that reinscribes (or queers) each and the relations between them’.26Today, queer theory is an umbrella term used to describe many different perspectives, not all of them compatible. It is difficult to do any of these justice through a simple summary, but this does not exempt one from accounting for one’s own position: Thus, I argue – based on my limited and localised knowledge – in favour of two different queer theoretical angles on Zahrtmann’s art simultaneously. A number of his works show homosexual motifs and themes – these concern the idea of queer as category and identity. At the same time, a larger quantity of works is involved in undermining norms, confusing us and offering alternative readings, which often, but not always, deal with gender, identity and desire – these concern queering as process and action. As will become apparent later on, Zahrtmann labours to create a place, in his life and in his art, which can both accommodate queer identity and which is queer in its indeterminate latency.

The ability to freely explore Zahrtmann’s substantial body of work – his biographer, Danneskjold-Samsøe, lists a total of 1,216 paintings and larger drawings – for all things different, queer and contrary to habitual ideas of gender, is partly a modern skill. Today, we are prepped (perhaps excessively so) to look for sexual meaning and content in images and to deconstruct works in order to search for the parodic and the self-contradictory.27 Given this present-day perspective, we may be puzzled by the general tendency among observers in his own day to ignore or overlook what seem to us obvious themes in Zahrtmann’s art – both before and after Prometheus – but what appears overtly, even glaringly visible to us may then have been mere hints, a code to be deciphered by those who, based on their own experiences, could ‘read between the lines’.

One example would be Loki from 1912, a painting which appears blatantly erotic and gay from a present-day perspective: the black-haired, olive-skinned, physically fit model looks smilingly to one side, suggestively holding his lethal mistletoe. The forking branches that serve as his seat and the natural scenery around him create an intimate, cave-like feel, and the clearly differentiated surfaces – a Zahrtmann speciality – activate a tactile, sensuous gaze. In terms of iconography, decoding the scene requires familiarity with the myth of the death of Balder from The Younger Edda, in which the ‘light’ god dies from a (penetrating) arrow shot due to the scheming of the ‘dark’ god.28 The painting is redolent with sultry seductiveness and dangerous sexuality. And when, in 1912, it was hung at Den frie Udstilling alongside works such as Grief, 1911 [fig.8], it prompted a kind of transference – the Loki scene becomes ‘contagious’, it goes ‘epidemic’ or ‘viral’.29 What is queer in a strictly categorial sense – the gay image of Loki – also queers something through its action, thereby challenging and rewriting expectations. One suddenly suspects that the crouched-up figure in Grief is too theatrical, the scene too blatant and vaguely parodic, or that Sofus Schandorph and Victor Emanuel (current whereabouts unknown) depicts more than simply an innocent meeting between two men, or that a range of other works mean more than they allow to show on the surface. Loki augments or launches such queer readings – because the exhibition context and the proximity between works always contribute to, direct and create meaning.30 Together, the works become too much, they infect Zahrtmann’s self-portrait and the other paintings at Den frie Udstilling in 1912, indeed, they can be said to suggest that one ought to reconfigure one’s understanding of all of Zahrtmann’s work; and perhaps of him too while we’re at it.

The reception of queer Zahrtmann in his own day

Of course, ascertaining how the various audiences of the day actually responded to the queer aspects of Zahrtmann’s painting as presented at, for example, Den frie Udstilling in 1912, is subject to considerable obstacles, but new works from his hand would routinely have reached a very wide audience – through popular exhibitions and through illustrations in newspapers.31 Empirical evidence of historical reception is typically highly mediated; it mainly involves critics and reviewers speaking. By its very nature, the reception of all things contrary, merely hinted at and partially subversive, will be passed down less clearly. Nevertheless, there is something to be gained from a careful, interpretative approach where we read the works concurrently with what was written about them in their day. Such critical readings cannot reconstruct the past, but they can ‘archeologically’ expose a space of (likely) scenarios:32 What might people see, think and say about Zahrtmann’s work; what ‘codes’ might they draw on?

In the above, I have argued that at Kristian Zahrtmann’s time, art criticism would mostly understand art based on an empathy with and sensitivity to character – the artist’s and/or the work’s – and that in practice, this led to artistic judgments based on how that character resonated with the critic’s own character, his own experiences and values. Thus, art appreciation came to be about brief, rapidly made assessments that relied strongly on the viewer’s self-image and pre-formed opinions. Such assessments reflect the viewer’s personality and horizon – who he or she is – which in turn makes viewers very careful about what they say. It is important to note the crucial difference between this approach and the historically aware, interpretive and contextualising methods that prevail today, methods which arise out of a fundamentally different view of art as a learning space.

To illustrate the question of what observers could see and allow themselves to talk about, critics and allies alike were, as was mentioned above, keen to point out the ‘paradox’ of Zahrtmann’s art and person. Seen from a present-day perspective, this could be interpreted as sensitivity to the processually ‘offbeat’, parodic and queer aspect that we now find so obvious in many of his artworks. However, using concepts such as ‘paradox’ may also denote an unwillingness to speak openly about the confusing topics and explicitly erotic images produced by Zahrtmann’s hand from around the time of Prometheus onwards; it may even take the form of a downright rejection made without mentioning the nub of the matter. Explicitly acknowledging the queer and homoerotic aspects of Zahrtmann’s imagery might backfire on the critic himself – ‘it takes one to know one’. Thus, a smaller group of critics distanced themselves from Zahrtmann’s art through gendered and sexualized terms without a clear addressee, for example when appraising the image of Loki: ‘One is growing increasingly weary of these well-formed male model studies, which, clad in jewelled fripperies, adorn themselves with the most exalted of mythological names’.33 Other critics drop hints or adopt an ironic distance that may easily prompt well-informed present-day readers to wonder just how much and what they see:

Zahrtmann’s Loki is technically brilliant: a superbly modelled and elegantly painted study of a male nude, limber and crowned by a headpiece, testing a twig of mistletoe for its suitability as an arrow while his effeminate gaze is distant and dreamy, perhaps plotting the next steps in furthering his intentions. The scene is set in a strange, fungoid, toxic forest landscape with lighting to match, and while one is not entirely satisfied with this perception of the Loki figure, it is by no means far off the mark, mischievous and sly as he is.34

When comparing various pieces of criticism of Zahrtmann’s works voiced at the time, we see that there are plenty of examples of how the works are actually perceived as queer, prompting three possible responses: (a) ignoring, (b) rejecting or (c) playfully hinting at their queerness. The latter happened surprisingly frequently, as in the reviews of Zahrtmann’s Adam from 1913–14. Using the rather more telling alternative title of the work – Adam Bored in the Garden of Eden – a critic writing in Hovedstaden points out that the ‘reading’ of the work depends on the observer’s ability to decipher it:

It will nevertheless attract colossal attention due to the nature of its subject. Our Biblical ancestor is portrayed as a fair, slim youth of glorious physique. He is, of course, naked, and all around him the lush, brightly coloured flowers and foliage of Paradise rise up abundantly in radiant Zahrtmannesque colours. But Adam looks melancholy. For what is he yearning? And where is Eva? Why is he bored? The mischievous old Master gives no answer. The solution to the riddle is for the viewer to find! Why not take a guess yourself.35

At Den frie Udstilling in 1914, Adam is exhibited amidst a selection of approximately fifty works spanning all of Zahrtmann’s career. Once again, the exceedingly queer painting cannot help but ‘infect’ everything around it. However, one outraged letter to the editor printed in København misunderstands the intended audience of the painting, expressing regret at how ‘ […] young girls absolutely cannot be seen […]’ to be visiting the exhibition (my emphasis).36 Other critics write – in more or less roundabout, in-the-know ways – up against the queerness of the work, creating a kind of reception that dares not speak its name: unable to overtly reveal what the critic knows, it becomes queer itself in its own paradoxicality:

However, his ideas can also occasionally be infused by a certain degree of youthful levity. Take this ‘Adam’, for example. We recollect that the serpent came into his life before he came to eat his bread ‘by the sweat of his brow’. Yet this athlete seems to have been shaped by much toil. – look at the build of his legs – his hands, accustomed to manual labour – the muscles of his neck! And we have learned that the serpent coiled around the trunk of tree, and that Eve was there, and, suspecting that this is a puzzle picture, we search for her among the voluptuous aralia, cannas, chrysanthemums and bananas. Perhaps the scene depicts a subsequent meeting with the serpent – it might look as if it and Adam were discussing the Fall and its consequences. Unless the serpent symbolises – Eve!37

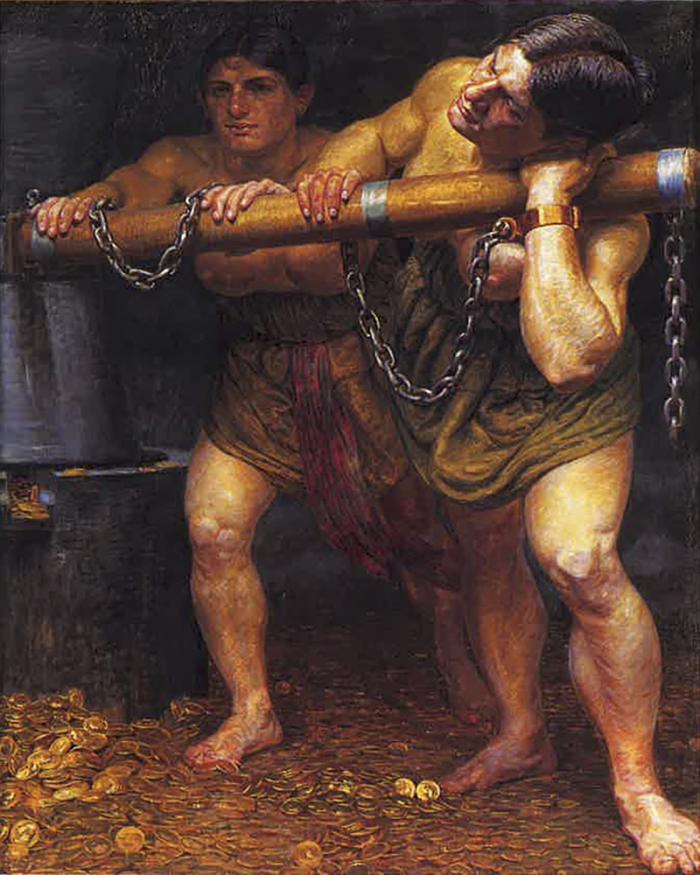

Looking at Zahrtmann’s paintings from 1904 onwards is to see another place opening up – a realm of beautiful, physically fit men who parade themselves for our viewing pleasure: Nero (1903), Prometheus (1904), Loke (1912), Adam (1914), A Victor (1915). A realm where gender roles are challenged: Susannah and the Elders (1906-07), Queen Christina in the Palazzo Corsini (1908) [fig.9-10]. And a world where sexuality is queered: Fenja and Menja in Chains Grinding Gold for Frode Fredegod (1906), Socrates and Alcibiades (1907 and 1911), The Prodigal Son (1906–09), Milk Test (1912–13) [fig.11-13].

This world is a place capable of accommodating several kinds of desires, it offers itself up as a colourful alternative to the grey and boring everyday city life of Copenhagen, and it brings warmth, intimacy and sensuality to the fore. But it is also a world and a place to which access is restricted: it presupposes an implicit sympathy – an element of complicit co-creation. Given the restrictive norms of the age, including its tendencies to oppress minorities, it is hardly surprising that many of Zahrtmann’s queer paintings are painted with a sense of parody and paradox quivering right at the tip of the brush. In those cases where things are becoming too clear, or too peculiar, friends and allies step in to smooth things over, insisting that nothing is meant in earnest, it is just a bit of fun [fig.14-15]. Indeed, believing anything else, accepting the images at face value would reflect badly on any defenders – perhaps putting their ‘character’ in an unflattering light.

Queering is a key element in Kristian Zahrtmann’s art after Prometheus; certainly when observed from our present-day privileged vantage point. Nothing in Zahrtmann’s extensive production pretends to be anything other than constructs, and he himself creates on the basis of a selective, artistic tradition – he is no naturalist. Ever since the 1860s, his art represents an elaborate dream of being able to enter other worlds, regardless of whether those places reside in the past, in the imagination or simply hidden behind curtains and closed doors. The dream of such a more accommodating place, its possibility subtly hinted at, is a particularly characteristic trait of Zahrtmann’s queer art; it is also a general recurring trope of centuries of queer art.38 One may reasonably say that his body of work possesses a certain queer processuality insofar as it renders possible the dream of another world that strives to evade the narrow confines of accepted norms. More on this later.

The overall perception of Zahrtmann in art history and posterity

In its appreciation of Kristian Zahrtmann as a person and as an artist, posterity has had few positive things to say about his queer project – it has been passed by in silence, or his queer paintings have been dismissed as bad art compared to his ‘healthy’ main masterpieces.39 The general plurality seen in the reception of any artist through a succession of exhibitions, media coverage and art criticism typically disappears when the posthumous story of an artist is written. In the case of Zahrtmann, as for so many others, this narrative is made ‘art historical’, complete with all the associated stylistic flourishes and emphases on some matters over others, and it is written by people who are so sympathetic towards the artist – why else embark on such a project? – that they downplay all the awkward and challenging parts.40 As a discipline, art history tends towards streamlining and imposing consistency on the link between life and work.41 The trend is clearly evident in the case of Kristian Zahrtmann, but does nothing to further our understanding of his complex, diverse, pluralistic production.

The foundations of the image of Zahrtmann presented in connection with his seventieth birthday were laid down at an early stage. In 1885, the art historian and later director of the National Gallery of Denmark, Karl Madsen, wrote a long article about Zahrtmann as a painter of ‘universally human, spiritual matters’ and as a ‘psychological history painter’, all while focusing on his depictions of Leonora Christina. The article reaffirms a particular view of Zahrtmann’s art that becomes prevalent not just in academic circles, but among larger audiences too: he is seen as a seeker of truth, non-idealising, and founded in a total identification with his chosen subject matter and the psychological space he conjures up.42 The art collector H. Chr. Christensen, who published inventories of the oeuvres of key Danish artists, also worked with Zahrtmann on charting his life’s work while the artist was still alive.43 Two years after the death of Zahrtmann, the printer and publisher F. Hendriksen published a large commemorative book, Mindebog, featuring a selection of Zahrtmann’s letters, carefully edited by his family, as well as various memoirs and recollections of his published through the years.44 In 1942, Sophus Danneskjold-Samsøe publishes a large monograph and inventory of the artist’s work, placing emphasis on formal artistic traits such as colour, mode of expression, composition and earnest empathy with the chosen subject matter, privileging Zahrtmann’s efforts as a history painter and a portrayer of Italy.45 By this time, Zahrtmann (and his mother!) remained sufficiently popular with the general public to make him the subject of a special Sunday supplement to the newspaper Berlingske Tidende.46

In 1979, the general interest in Zahrtmann as an educator is revived with Hanne Honnens de Lichtenberg’s Zahrtmanns skole, a book which draws partly on his letters, partly on his pupils’ memories. Seen from this later vantage point, Zahrtmann’s efforts as a teacher are regarded as ‘a significant precondition of the breakthrough of modern painting in Denmark’.47 The established approach to Zahrtmann’s production, evident in newspapers in 1913 and as far back as Madsen’s 1885 article, is continued, with emphasis on various particular traits, in exhibitions and accompanying publications on his images of Leonora Christina and Italian scenes,48 and in a large monographic exhibition in 1999.49 Examples of this traditional reception of Zahrtmann, omitting his queer project, can be found as late as in 2006 in the exhibition catalogue Ære være Leonora (no English title).50 Zahrtmann is still primarily regarded as a history painter specialising in the story of Leonora Christina and in Italian folk scenes – or as an educator acting as a helpmeet to subsequent generations of Danish art.

Concurrently with this, work was also being done outside the museum institution which actually pointed in another direction, specifically Morten Steen Hansen’s pioneering, but unpublished research thesis from 1993, Kristian Zahrtmann. En homoseksuel kunstneridentitet i Danmark omkring århundredeskiftet og den kunstneriske fremstilling af homoseksualiteten i Nordeuropa (Kristian Zahrtmann. A homosexual artist’s identity in Denmark around the turn of the century and artistic depictions of homosexuality in Northern Europe).51 Hansen’s brief thesis connects parts of Zahrtmann’s work with homosexual culture and imagery in Denmark and Europe, presenting a range of very compelling analyses of his art. Critical of a Freudian approach to Zahrtmann, Hansen instead focuses on the artist’s practices, which can be interpreted in terms of a homosexual identity in keeping with his time – examples include the fondness for exclusively male communities, particular clothes/costumes and home décor – and how he is perceived by media and the public, where images and reviews describe him in terms of femininely coded signifiers. Hansen’s thesis interprets aspects of Zahrtmann’s life and work in a productive dialogue with sexuality, gender and history without reducing or essentialising any of these aspects.

The perspectives pioneered by Morten Steen Hansen are summarised and elaborated on in an article and, later, a quite small themed display with no accompanying catalogue called Fokus på Zahrtmann. Kroppen og historien (Focus on Zahrtmann. Body and History) at the National Gallery of Denmark in 2002.52 The year before, the museum acquired Socrates and Alcibiades from 1911, one of the first explicitly queer works by the artist in public ownership. A lull follows until 2011, at which point Louise Wolthers, taking her point of departure in the same museum and a rehang of the collection, is the first scholar to undertake an assessment of Zahrtmann that explicitly announces itself to be based on queer theory.53

Steen Hansen’s rethinking of Zahrtmann takes place at a time when queer theory and theories of performativity are still in their infancy – Judith Butler’s seminal Gender Trouble was published in 1990 – and in Denmark, art history studies have barely begun working with poststructuralism, which later became such a major influence. Perhaps the effort was made too soon to have real impact? The majority of Danish museum exhibitions and the research conducted as part of them offer little or no productive reassessment of Kristian Zahrtmann’s life and work, a fact which reveals a thought-provoking inertia within Danish art history. One might tentatively take the view that in recent years, Danish museum-based art historians have ‘inherited’ the fear of recognising Zahrtmann’s queer project from the older reception of his work, and also that a long-gone social fear of grappling with the issue continues to live on in an institutional lack of ability and wish to engage oneself in this project.

As the ‘new museology’ movement of the 1990s has gained ground in wider circles, harsh critique of power has been supplemented by the museums’ and authorities’ own, softer discussion of their responsibilities in terms of developing tolerance, citizenship, knowledge and new insights in all of us.54 Regardless of the specific values prioritised at any given time, there has been a gradual shift from authoritative one-way communication to a more constructivist understanding of how insight is created in the meeting between audience, art and institution. This also means that the museum institution must speak with its recipients based on their backgrounds, interests and life experiences.55 For the same simple reason, it makes no sense today to omit or overlook a significant part of Kristian Zahrtmann’s project; quite the contrary, it makes perfect sense to emphasise an early queer artist’s work for the benefit of a diverse audience. Returning to the project at hand, Zahrtmann’s work to conjure up another world and his quest for a place for as-yet unspoken opportunities seems most relevant here

At home with Zahrtmann

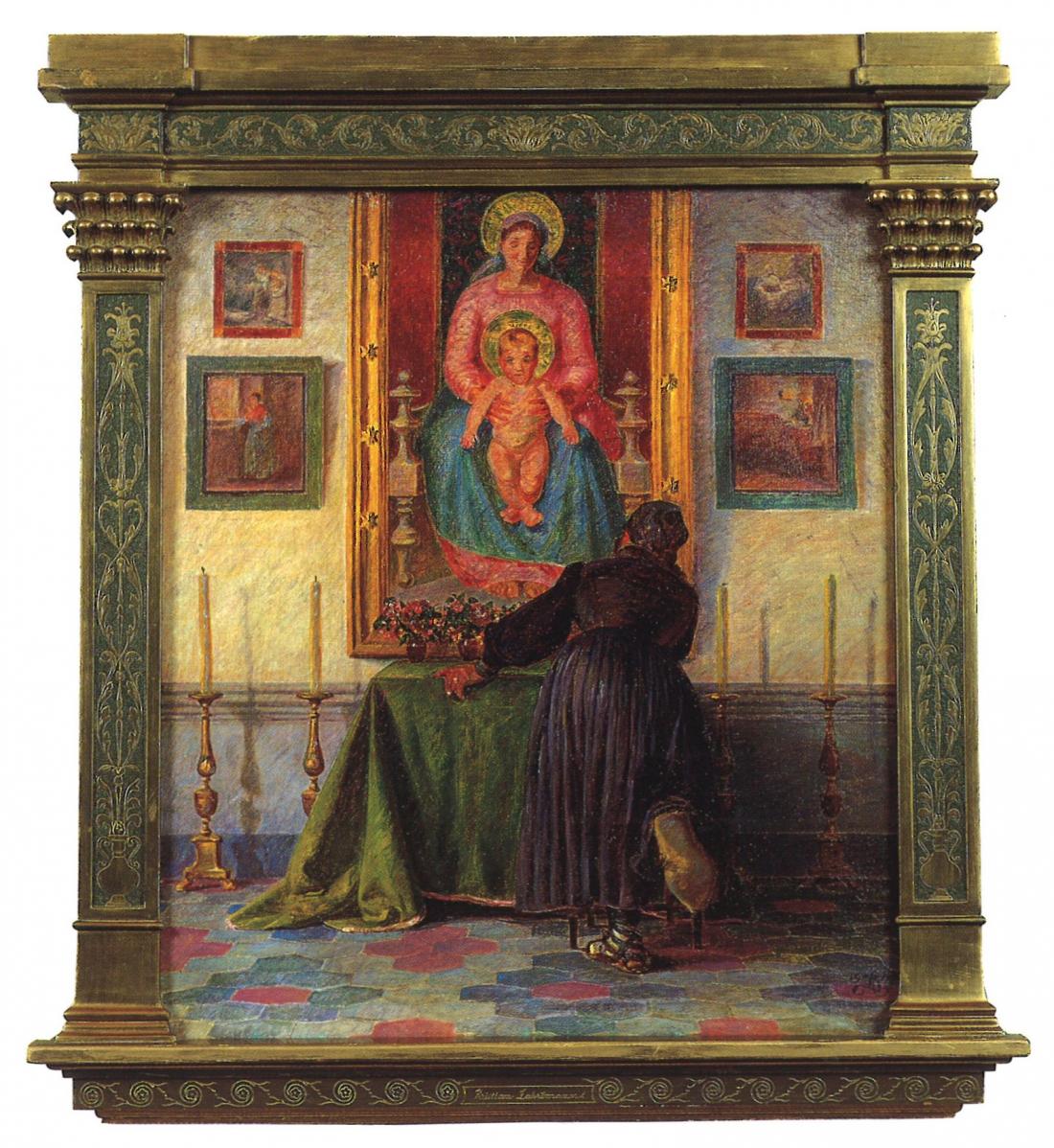

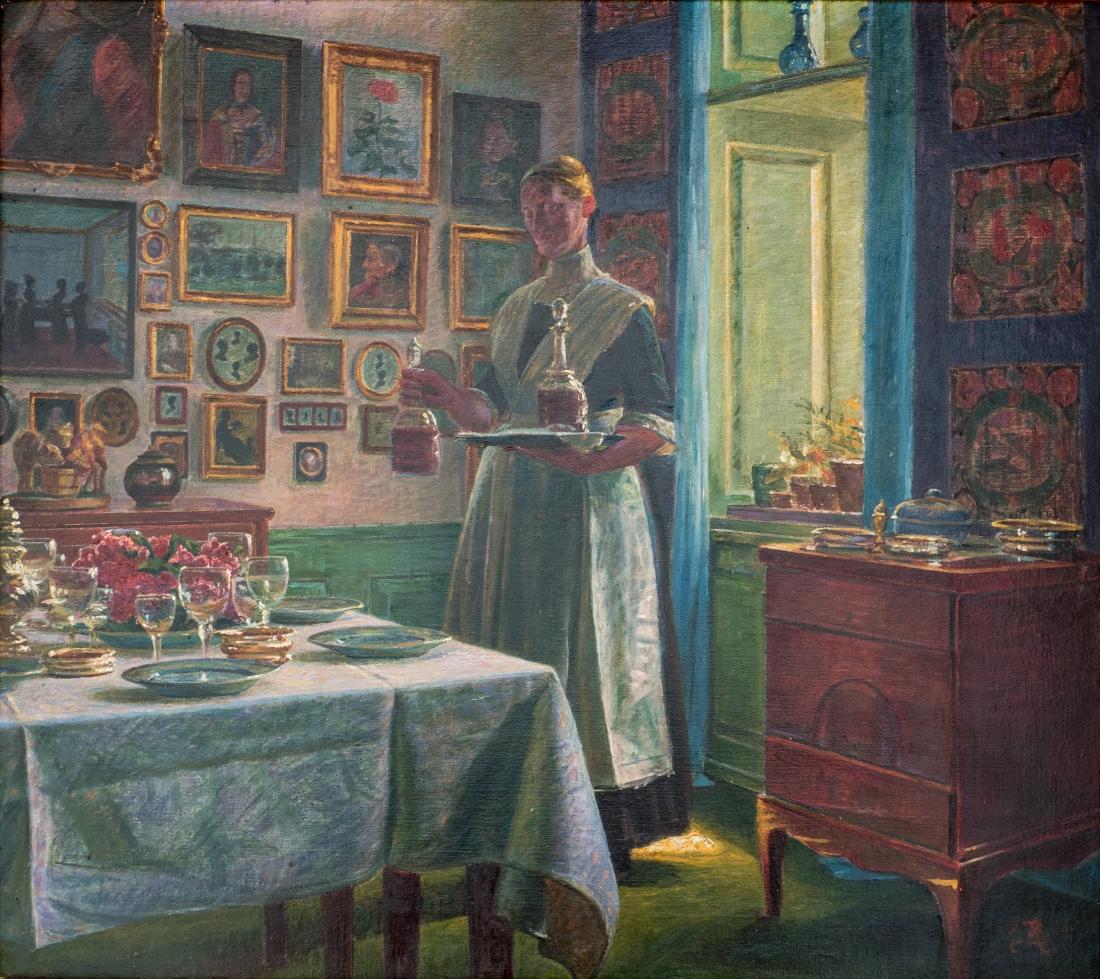

In connection with the celebrations of Zahrtmann’s birthday, one specific place attracted particular attention in the press – his home in his villa, Casa d’Antino [figs.16–17]. Articles and illustrated pieces spoke about visits to the artist’s home, letting the house, its décor, the studio-cum-parlour and the garden amalgamate with Kristian Zahrtmann the man to form a total portrait.56 Several of his students’ portraits of him ‘at home’ were also reproduced.57 Prior to this, Zahrtmann had already introduced the themes of home and studio in his own art [figs.18–20] – sometimes indirectly, as in paintings such as the Biblical narrative about The Prodigal Son, 1906–09, which is set in his home in Amaliegade and was shown at Den frie Udstilling in 1909.58

As a generous, willing host and interviewee, Zahrtmann co-authors the persona created by media portraits of the artist and his home, working in concord with his own paintings. Zahrtmann is performed and mediated via the press and via exhibitions of his paintings – he contributes to the production of postcards and photographs of himself in his home, and he has enough celebrity clout to be ‘pinned in place’ by Politiken in 1913 by being filmed at Casa d’Antino.59 Throughout his career, and increasingly after 1900, Zahrtmann placed his own furniture, costumes, fabrics and objets d’art in his history paintings. For those in the know, these objects may introduce a discordant note, a kind of creative disruption that identifies the image as being produced in the here and now – art historian Karl Madsen was among the first to remark on deliberately anachronistic features in Zahrtmann’s art60 – but they also become signs of Zahrtmann the person by dint of his ownership. This is to say that the artist has a dual presence in these paintings, partly through the index of the clear signatures, and partly through the metonymic references made by the objects depicted.

Paintings such as The Prodigal Son and the genre fantasy In the Sacristy 1913, [fig.21] see the theme further developed, setting the scenes in surroundings that resemble Zahrtmann’s combined home and studio. As Rikke Zinck Jensen says, Zahrtmann’s history paintings tend to take place in enclosed spaces – as if on a stage – a point which she links to Zahrtmann’s queering of gender conventions where the ‘natural’ expectations regarding masculinity and femininity are challenged and shown to be constructs.61

Building on this analysis, one may say that the challenge of conventions is increasingly set against a backdrop of home – specifically one that looks like Zahrtmann’s home – which accordingly becomes one of the key referents of an increasingly queer artistic practice. And, as I shall argue in a moment, around the year 1900 the idea of home is pregnant with meaning, both ideologically and artistically.

Zahrtmann moves into Casa d’Antino, a villa he himself had built, in November 1912.62 The media report this event as a kind of ultimate fruition, of things coming together, describing how well the setting of his new life reflects him as a person. The latent conflation, always looming in the background of media reports, between Zahrtmann and the historic figure of Leonora Christina can be said to be brought to a head by the artist himself when, in 1914, he paints her in Casa d’Antino, using it as a stand-in for the convent in Maribo that served as her home upon her release from captivity. In Zahrtmann’s hands, the life of Leonora is presented as a kind of hagiography, a biography of a saint, ending with a variant of transcendence as she is set free from prison. It is tempting to see this as an example of Zahrtmann painting himself (by proxy) in his new home, reading the Holy Scriptures – a metaphor of being free, liberated, freshly elevated to a new and spiritual level of existence. Regardless of the exact angle adopted, it is difficult not to see something quite significant in Zahrtmann’s use of his home and his belongings as references.

In his article on Kristian Zahrtmann, Plato’s Symposium and Zahrtmann’s two paintings of Socrates and Alcibiades, Michael Hatt analyses how the artist strives, in his art, to develop a homosexual identity as a third way between vitalism and decadence. Around this time, the possible homosexual and queer identities are poised somewhere between medical definitions and criminal prosecution, outrage and disgust expressed in media and mass meetings, and a few, more or less public queer people, such as the author Herman Bang or the poet Walt Whitman, who represent something positive, creative and self-determined.63 Referring to Jensen’s and Hatt’s articles on Zahrtmann, one might argue that Zahrtmann’s paintings of strong and tragic female figures,64 his depictions of clergymen in prayer, his male nudes from the realms of literature and the imagination – all of these subjects form part of an identity-defining project: the portrayals of women present historical and fictional characters as trailblazers in which the observers may see themselves reflected as they wish, but which also challenge and subvert the general beliefs in ‘natural’ gender roles and standards for what it means to be a man or a woman. Other works, such as Socrates and Alcibiades, A Victor or his paintings of men lost in reading and contemplation [fig.22] offer different avenues of approach to creating a new, self-determined identity capable of accommodating spirit, body and (mainly homosexual) desire in new ways. Hatt’s and Jensen’s articles delve into details to demonstrate that Zahrtmann is not just a painter of queer subjects, but in the process of building a queer and homosexual identity through deliberate challenges, development and construction.

In an influential essay from 1996, ‘Imminent Domain: Queer Space and the Built Environment’, the art historian Christopher Reed highlights the crucial importance of space and place for queer identity.65 Reed argues that historically, a struggle has been fought to create specific spaces where queer persons have been able to meet and express themselves – such as bars, clubs, societies and cruising scenes – but that the work to promote queer ‘spatiality’ should also be understood as work aimed at opening up new opportunities. ‘Queer’ denotes something that may and can take place somewhere, something that is more or less immanent and not necessarily manifest within a given space. Reed speaks primarily into an American context, centring on 1980s activism and efforts to carve out a space in the public urban space, and if one turns one’s gaze towards the realities of Copenhagen around 1900, the potential queer spaces are even more ephemeral and invisible: in public, they are limited to a few settings within the city where one could go in search of sex, and a number of homosocial communities in the form of clubs, societies and (Vitalist) sports. Kristian Zahrtmann’s increasing use of references to his home points to that other place where queer identity can be formed and find expression. But he is not alone in using ‘home’ as the springboard of a sophisticated artistic project at this time.

Zahrtmann, Hammershøi and ‘home’

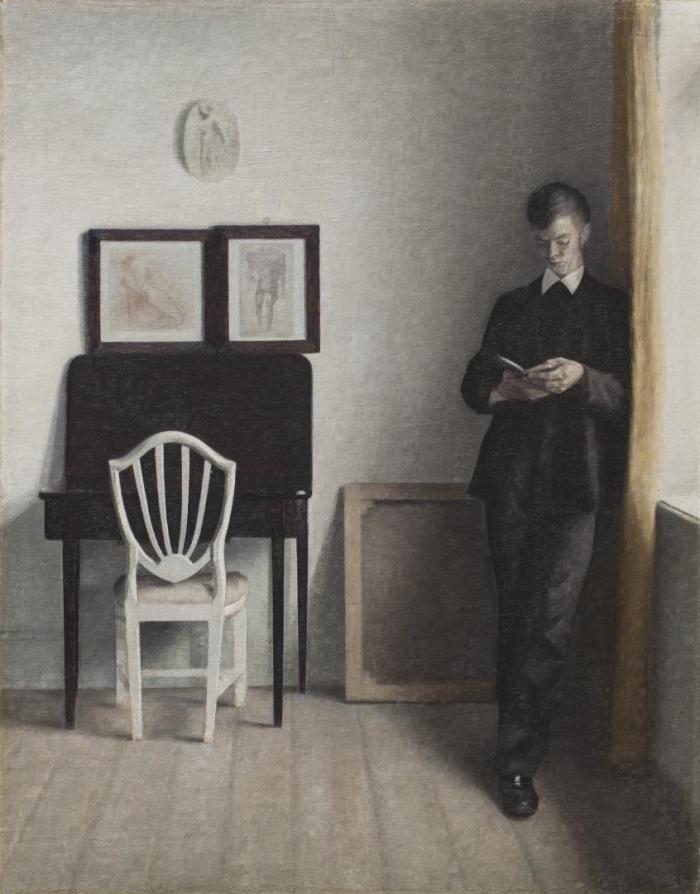

‘By some strange twist of fate, the paintings of Vilh. Hammershøj and Kr. Zahrtmann have come to hang directly opposite one another’,66 states Dagens Nyheder in 1891 in a review of the first instalment of Den frie Udstilling. Zahrtmann and Hammershøi would continue to follow each other in exhibition contexts for the rest of their lives – often compared and often contrasted: ‘[…] the polar opposites of Danish painting: Hammershøj, abstainer from colour, and Zahrtmann, who sings its praises in the loudest tones imaginable’.67However, other reviewers also point towards a kinship that concerns a similar flair for composition,68 pointing out that both are ‘masters of nuance’.69 And comparisons yield up more than superficial insights: it is remarkable to see how two so obviously different artists both turn to planes of very tactile paint in order to create atmospheric interiors, and how both focus intensely on space, spatiality and pronounced tension between barriers and openings [fig.23]. Zahrtmann’s interior scenes usually take their point of departure in established iconography – they use an existing narrative – which the painting’s atmospheric interior transforms and makes the artist’s own. By contrast, and in Modernist fashion, Hammershøi abandons history painting, allowing the interior to become a narrative in its own right. A crucial shared trait for both artists, who were friends and part of the circle collaborating on Den frie Udstilling,70 is the prominent use of one’s own home – not as the basis for everyday realism or anecdotal scenes of family life, but as a framework for innovative artistic projects.

Up through the nineteenth century, the concept of home had been the object of growing interest, and the notion of the ‘home-like’ took on strongly positive connotations.71 The rise of the bourgeoisie saw a concurrent gradual increase in the distinction between the private and the public, and the home became ideologically separate from what is ‘out there’, instead becoming the place you go in search of peace, recuperation and intimacy in order to be and become ‘oneself’.72 Around 1900, greater emphasis is placed on how aesthetics, interior design and functionality affect and promote mental health, particularly by writers such as Ellen Key and Edith Wharton, who, like the greatest advocate of the practical villa, Hermann Muthesius,73 drew inspiration from the English Arts and Crafts movement. ‘Interiors’ and the decoration of the home is now seen as something other and more than a random setting, becoming regarded as an intimate reflection of the mind of its inhabitant – there are reasons why modern psychology and perceptions of the individual arise in the drawing rooms of the haute bourgeoisie.74

When Zahrtmann and Hammershøi use their homes as recognisable points of reference, they very clearly build on the period’s general views on the key importance of home in forming and reflecting identity and character. Generally speaking, those who painted interiors around this time express a certain tension between the concepts of the public and the private – if the world is a stage and the home is ‘backstage’,75 where does this leave the artists’ dramatic, even theatrical staging of their own home? Unlike fellow Scandinavian artists such as Carl Larsson and Peter Hansen, who mobilise the distinctive authenticity inherent in turning the private into something public, one cannot exactly describe the spaces depicted by Hammershøi and Zahrtmann as settings of normative family life. Referencing a famous text by psychologist Sigmund Freud, Felix Krämer describes the interiors painted by a group of Modernist artists – including the quiet rooms evoked by Hammershøi – as ‘uncanny’, in German unheimlich, literally ‘un-homelike’. Such art challenges the idea, widespread at the time, of the home as a serene, unproblematic place, introducing aspects such as sexual tensions, uncertainty and veiled allusions.

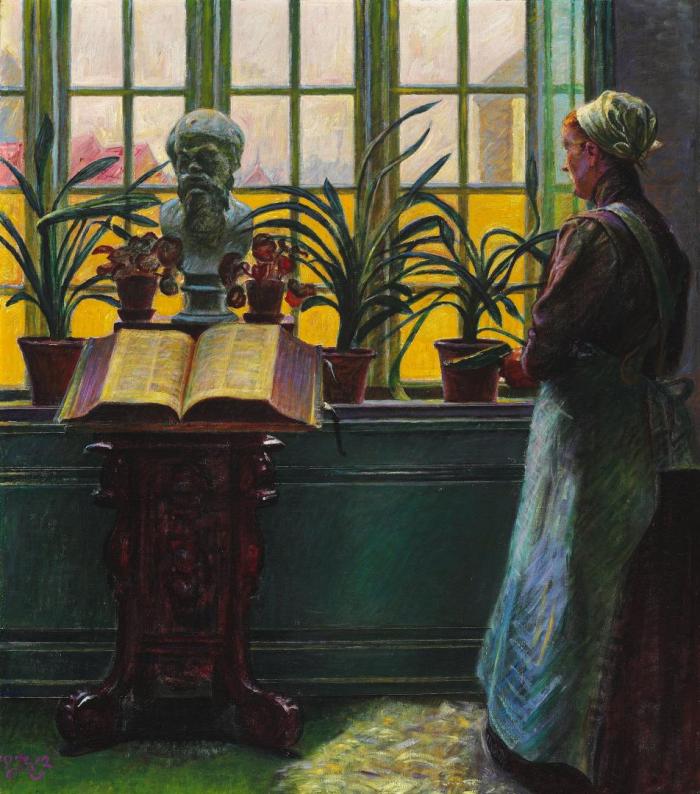

The references to Hammershøi – who has since become an artist with infinitely more prestige attached to his name – serve to make it clear that Zahrtmann’s project is also not ‘just’ about a personal point of departure. Zahrtmann quite inevitably touches upon the ongoing discussions of his time about bourgeois morals, sexuality, coupledom, obligations and self-fulfilment, all of them rooted in the idea of home and the distinction between the private and the public. The one thing that Zahrtmann does differently is to express a coded desire for an entirely new identity beyond that of heterosexual norms: Michael Hatt analyses At the Bible Table [fig.24] as a queer self-portrait,76 and a handful of other late paintings by Zahrtmann, such as his androgynous personification of Peace in his studio, contribute to queering his entire home and persona to such an extent that they in turn ‘infect’ all of Zahrtmann’s pictures from his home: for example, it feels natural to see the two almost identical self-portraits from 1916 (Bornholm Art Museum) as inscribing Zahrtmann in the queer space established in Zahrtmann’s art; the backgrounds seen in his self-portraits hold several of his queer paintings. Pointing back to Christopher Reed, Zahrtmann succeeds in reaching beyond the realm of imagination to also find and create his own, actual place – the home as a queer space capable of accommodating new, as yet unspoken opportunities.

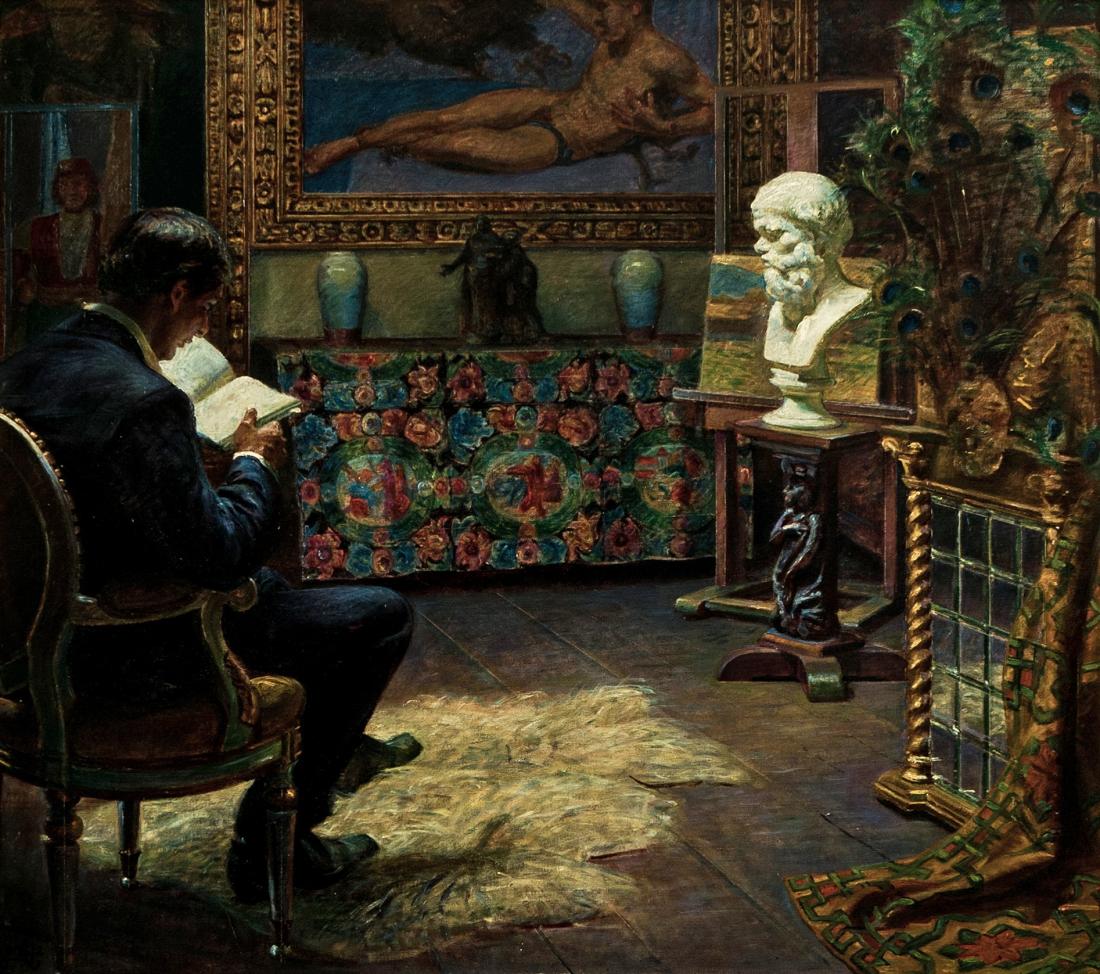

These as-yet-unspoken potentials unlocked by Zahrtmann’s work on the domestic realm might also extend to the dream of coupledom and togetherness. The portrait of Kaj Dessau features Zahrtmann’s distinctive and oft-reproduced folding screen embroidered with ‘Sienese pages’ in the backdrop [fig.25], and a 1906 portrait of the art dealer Peter Magnussen is clearly set in Zahrtmann’s home. However, the dream may be most clearly expressed in Interior with Young Man Reading from 1912. The anonymous man is clearly very much ‘at home’ in these surroundings, which look startlingly similar to Zahrtmann’s Amaliegade flat. The prominently placed bust of Socrates, whose sightline cuts across the painting and lands on the young reader, joins the centrally positioned painting of Prometheus in prompting thoughts of a homoerotic relationship, possibly between an older, dominant man and a younger, passive recipient. The eagle’s assault on the chained Prometheus suggests something violent and carnal, while the illuminated polar bear rug on the floor activates a tactile gaze, hinting at a rather softer fur on which to err and frolic. Encompassing all these elements, this small painting points to a dream of home as the setting of a relationship that can accommodate both sex and spiritual pursuits, possibly in the form of an older artist offering to ‘educate’ and ‘form’ a younger model. (One might wonder if this is the same beautiful, black-haired model that Zahrtmann used for Loki and Loki Presenting the Mistletoe to the Allfather)

Zahrtmann’s home-stead

Zahrtmann’s persona cannot be separated from our experience of his works; he incorporates criss-crossing references to himself, to his dreams and to the home which, given his contemporaries’ views of the private realm, must also be perceived as an extension and image of himself. Press reports tend to present Zahrtmann as a ‘collector’ and his home as a magical, fairy tale place,77 where gilt frames, objets d’art and Persian rugs combine to form an aesthetic redolent with condensed sensory appeal: ‘For this room is more than just old and precious furniture (of which there is plenty), more than thick rugs (which cover the vast expanse of floor), more than the most exquisite art on walls and shelves; it is a symphony woven out of all the themes of all that is tasteful and pleasant and comfortable, a lovely home for a man of spirit and intellect’.78

In recent history, the home/interior design has become a place offering a special opportunity to work relatively freely with queer identity while also sending clear signals to and for ‘those in the know’. The well-orchestrated, painstakingly decorated homosexual home occupies a hybrid space, poised between behaviours and spheres traditionally seen as either masculine or feminine.79 The queer home reaches directly into the heart of ideas about that which is most personal and private of all. So too does collecting, which has typically been separated out into a ‘feminine’, female realm of furniture, fabrics and smaller objets d’art – bordering on interior design – whereas large paintings, weapons and the like have been seen as more ‘masculine’ and, hence, manly. The idea of Zahrtmann as a ‘collector’, where the home itself is the collection, signals a similar hybridity of masculine and feminine interests. Like all private collections, its significance revolves around the collector himself, because all collectors ultimately collect themselves.80 One also gets the sense of Zahrtmann carrying out a deliberate ‘curating’ process in those paintings that are set in his home and refer to his own works – Prometheus in particular often appears in the background – as well as to art by others. Zahrtmann the man, his artistic production, his home and his collection of artefacts merge into a distinctive space of his own, a ‘home-stead’. Set in an era where ‘character’ is the crucial parameter when assessing art and artists alike, this hybrid place constitutes a powerful statement. But, like all collections, Zahrtmann’s home-stead is also always in flux, always evolving.

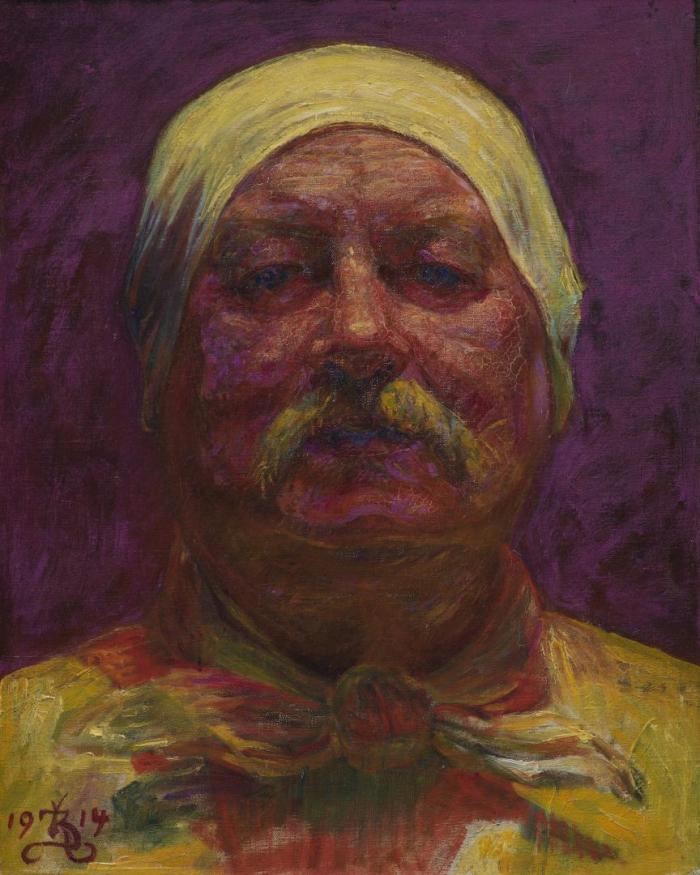

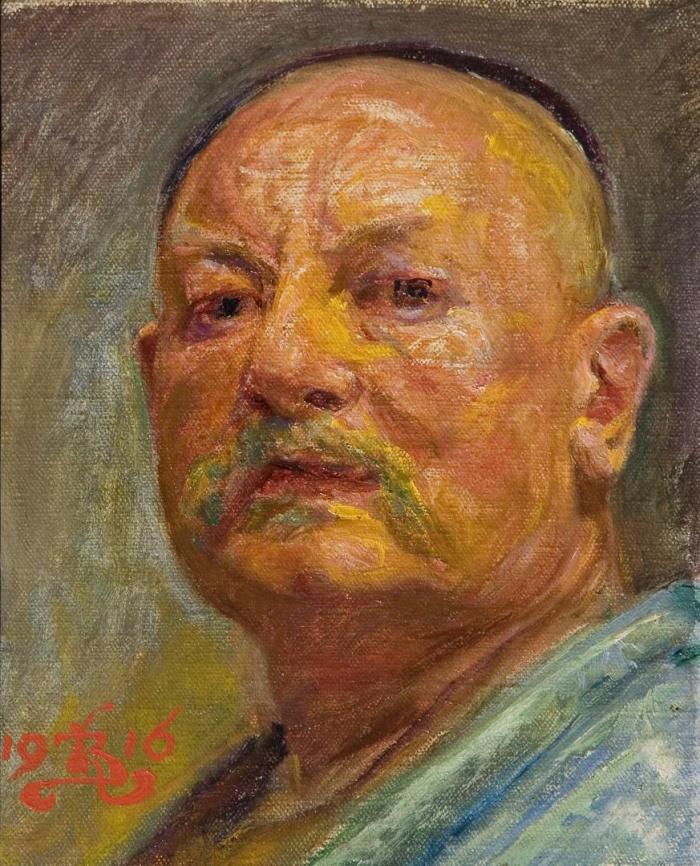

During the final years of his life, Zahrtmann created a number of rapidly painted, almost serial self-portraits set in his studio-parlour. Headgear and facial hair come and go, the lighting changes, and the handling of colours and brushwork is sometimes loose, sometimes tighter [fig.26-28]. Sophus Danneskjold-Samsøe, Zahrtmann’s biographer, takes a formalist starting point and is enthusiastic about these seemingly modernist paintings; works which might, in contrast to the rest of Zahrtmann’s late work, be perceived as autonomous exercises in form without any deep biographic significance.81 However, the kind of new criticism with which Danneskjold-Samsøe obviously had clear affinities back in 1942 never really worked well when considering queer art, a realm where author and work are always-already closely interwoven.82

Zahrtmann’s art was created during a time when sender and work were seen as a totality, and all of Zahrtmann’s queer project makes use of this conflation – both in practical and ideological terms. His final self-portraits are not a matter of formalism – quite the contrary, they make sense as the final step in his decades-long process of creating a persona. Zahrtmann is filmed, photographed, has his voice recorded, he is thoroughly documented and reported, and he exhibits art that refers to his home and studio over and over again. If anything, his concluding self-portraits form a kind of superstructure to his preceding efforts to create a place of his own, a home-stead – efforts that can be said to have had happy results in many ways. By this time, Zahrtmann has come so far in his self-defining, queer project that he is able to approach the question of his own identity and affinities in yet another new way; but he still cannot possibly let it go.

Zahrtmann paints portraits throughout his life, and like so many other artists he began with what happened to be at hand – his family and his childhood home.83 He also concludes his artistic endeavours by focusing on what is immediately to hand, which by this point means portraits of himself in his home, painted in his studio-parlour by the natural light streaming in through the huge studio window or by artificial light from lamps draped in red fabric. The strongly iconographic features have been pared away by this point; Zahrtmann’s home can no longer be recognised as such, so the observer needs to know in advance that this is where he produces his art – and his audience does know.

‘But, who knows Zahrtmann!’, stated Ernst Goldschmidt in his birthday greeting,84 and the answer must be that we know those aspects he calls forth and develops in conjunction with those of us who observe and see him. The overall picture of Zahrtmann is also changeable and playful, at times intimate and earnest, but always full of intertextual references calling out to be deciphered by those who know the codes. Today we are willing to read ‘between the lines’, and after a hundred years of new ideas we find it much easier to identify his queer project across his art and persona. Of course, this should in no way overshadow the sheer emotional impact of this essentially human endeavour: the bravery, entertainment value and poignancy of seeing a human being merge art, life and self-presentation in order to create a space that never existed before: a place of potential, scope and expression for a queer personality.

Thanks

Researching and writing the article has been made possible through a grant from the Ministry of Culture’s Research Council who also supported a number of workshops. I am grateful to Michael Hatt (University of Warwick), Patrik Steorn (Thielska Galleriet) and Rikke Zinck Jensen for their participation and for good discussions about the art of Kristian Zahrtmann.