Summary

Kristian Zahrtmann seeks to go beyond aesthetic conventions and social categories in many of his paintings. Men are allowed to be beautiful, vain and attractive, while women can be bullish, powerful and ugly – even if there are also many motifs where the gender roles are fairly conventional. Several of Zahrtmann’s works allow the viewer to revel in male beauty – the paintings give generous opportunities to ogle men and their charms.

Article

Even in the 1920s, Zahrtmann’s art was described by the Swedish art critic Georg Nordensvan as eccentric, paradoxical and emotional, but he also stressed that Zahrtmann’s “period of glory” was in nostalgic history painting and folklore scenes.1 His contribution as a teacher of a whole generation of young artists has been highlighted for its seminal influence in the development of Nordic art towards bolder colour in the early-20th century, ever since the art historian Hanne Honnens de Lichtenberg’s research in the 1970s.2 Zahrtmann’s way of allowing his temperament to permeate his practice and his ability to inspire the same quality in his students is another trait that is described as indicating a movement forwards, in this case towards the artist role of the modern era.

Since the 1990s, queer perspectives have been applied when interpreting the artistic practice of Zahrtmann. The art historian Morten Steen Hansen prefers to avoid a psycho-biographical reading of the artist and his works and instead looks at how established notions of homosexuality can add to our understanding of his identity and art.3 The art historian Erik Brodersen notes Zahrtmann’s keen eye for male beauty and interprets the artist’s growing interest in masculinity, sensualism and sexuality as tending towards Vitalist movements around that time.4 In connection with a new installation of the collections at the Statens Museum før Kunst, the art historian Louise Wolthers has paid particular attention to readings of Zahrtmann’s paintings from gender and queer perspectives. His works were included in an exhibition space that was to form an intervention in the established canon presented in the rest of the Museum.5

Zahrtmann was not alone in his fascination for the subject of naked men in the early 1900s. This essay places the motifs in an intellectual and visual setting, with a close reading of the imagery that allows for a homoerotic gaze in the midst of the overarching cultural and historical contexts. Parallels within Nordic art offer further perspectives and reveal other artists who, through their works, contribute to a widespread adulation of the athletic male body. Against this background, we will explore how the subject of naked men places Zahrtmann’s oeuvre at the centre of the aesthetic, cultural and social tendencies of his time.

The gaze of desire and nude men in art

In the 1800s, naked men became a taboo subject in art. In the late18th century, nude men were by far more popular than female bodies in painting, in conjunction with the male-dominated ideology of the French Revolution.6 Women’s bodies subsequently took precedence to the extent that they came to be one of the most dominant themes in both academic and modern art. With industrialism, the male body does not actually become more marginalised; it does, however, become more taboo and charged. The notions of how men related to each other changed, and boundaries became sharper between what was socially acceptable and unmentionable, on a sliding scale from homosocial friendship to homosexual desire.7

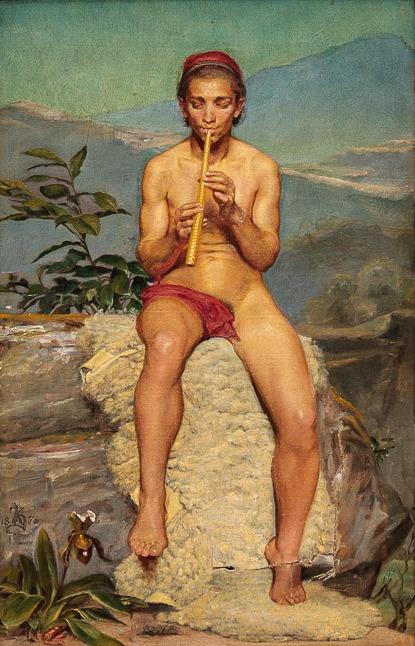

“Shepherd lads” and “fisher boys” were subjects that attracted both painters and sculptors throughout the 19th century, and were considered less daring, with portrayals of awakening and innocent sexuality and gentle masculinity. Nordic works in this genre include Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Shepherd Boy (1817), but also paintings by the Swedish artists Carl Gustaf Qvarnström, Neapolitan Fisher Boy (1852), Johan Peter Molin, Shepherd, Sitting on a Rock (1847), and Norwegian artist Christian Meyer Ross’s The Lizard-slayer (1888) A few of Zahrtmann’s early paintings, such as Samson (1876), A Sherpherd Boy (1876) [fig.1] and David in Saul’s Palace (1877), relate to neo-classicist dreams of a vanished Arcadia, with scenes that seem to hover between exotic dream and physical reality. To some extent, these motifs presage the imagery of the German photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden in the decades around 1900. Italian boys and young men pose naked in situations of idealised classicism and homoerotic fantasy. In the 19th century, a pictorial tradition was established in art and photography that offered homoerotic subjects in Mediterranean settings, both classical and modern.8

In art, heroic and idealised male bodies feature mainly in historical, mythological and biblical stories during this period. Among Kristian Zahrtmann’s paintings, Job and his Friends (1887) [fig.2] and The Lord Revealed Himself (1895) can serve as examples of these genres. It is characteristic, however, that the artist took an independent approach to the subjects, in that he intentionally combined the proneness of the bared body with a psychologically convincing vulnerability, transcending the traditional idealising and sentimental imagery.

It was in the 20th century that Zahrtmann specifically devoted himself to male nude in his artistic practice. But the artist’s astute observation of men and his ability to engage the viewer’s gaze is noticeable also in other parts of his oeuvre. A painting such as Students Leave to Defend Copenhagen in 1658 (1888) [fig.3] may seem like a typical contemporary moralising and educational history painting. A cursory glance would give the impression that all the models are in identical 17th-century costumes, but if we allow our gaze to linger on a couple of the young men’s appearances, we discover that they each have individual hair styles, eyes, cheeks, lips and other features. They all look into the distance, and the viewer is free to inspect and compare them to each other and perhaps choose a favourite. The military poses and drawn weapons allude to an underlying aggressiveness in the students, which might also pique the viewer’s excitement.

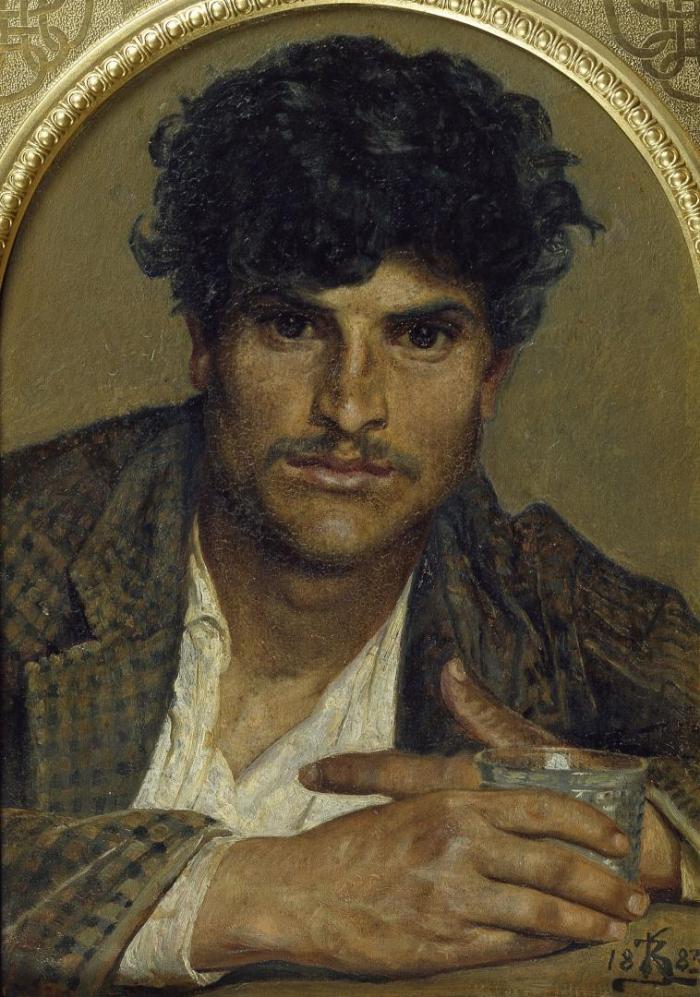

The painting Ambrogio, Cività d’Antino (1883) [fig.4] shows a handsome man who has discovered that he is being watched and meets the onlooker’s eye. His right hand holds a goblet, while he points to himself with his left, a gesture that says, “Who? Me?” It is not clear how the encounter will proceed – will there be flirting or conflict? Close scrutiny of male beauty is portrayed in paintings such as Head (Sudy) (1867), Masquerade (1882) [fig.5], King Solomon (1888) [fig.6], and Titus (1909), but several of these motifs lack the trembling moment and the tension that arises when the model suddenly looks at the viewer. Zahrtmann’s art gave him the opportunity to apply his skills in viewing men and masculinities, and the paintings show various kinds of positions, from the onlooker who spies inconspicuously in the legitimacy of an observing audience, to being caught staring, or initiating contact with a first glance.

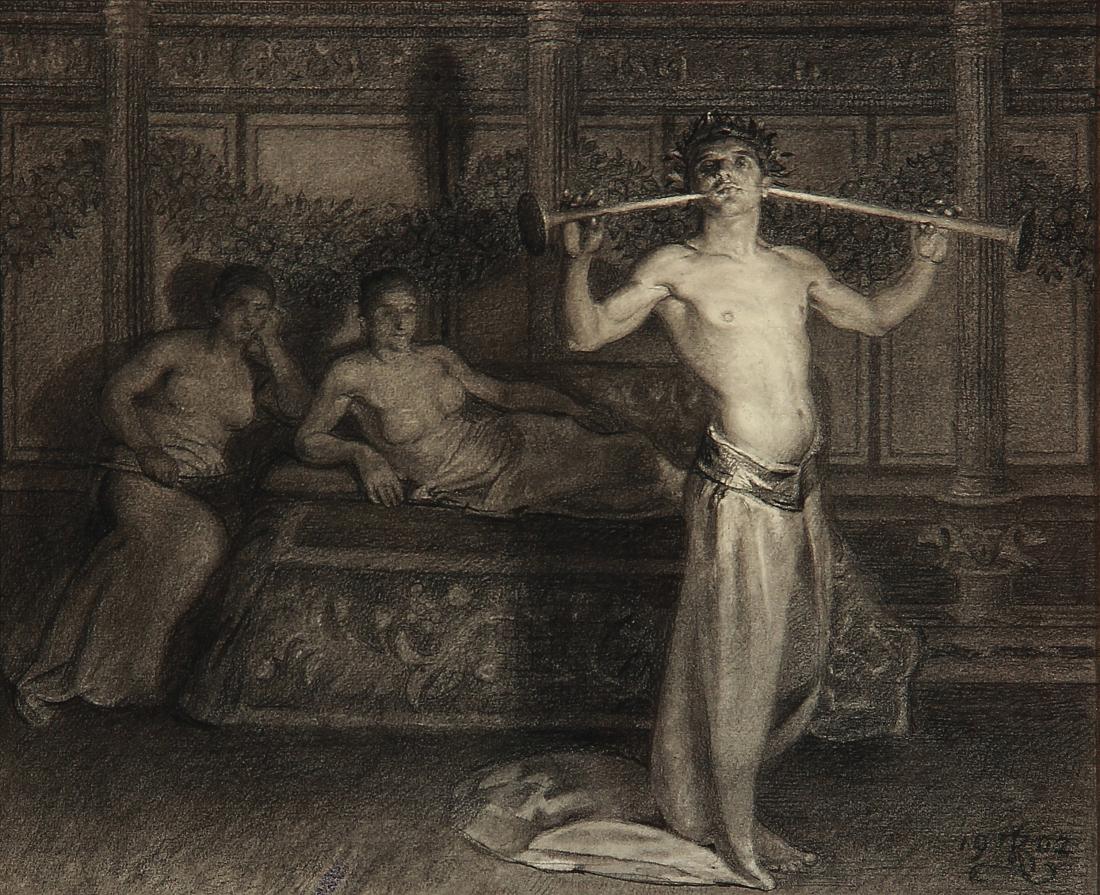

Zahrtmann’s oeuvre contains several paintings of men who are engaged in various activities. They play the guitar, walk around the garden, meditate or fall on their knees to pray. The men are absorbed in thought or music and seem entirely unaware of being watched. One painting on the theme of the pleasure of seeing is Nero (1902–03) [fig.7]. The Roman emperor’s reign is associated with a blossoming of the arts, but also with debauchery and tyranny, and he was criticised for valuing dance and singing above duty and responsibility. Nero knowingly makes himself the object of admiring glances in Zahrtmann’s take on the theme. His toned upper body is emphasised by the arms reaching upwards with a horn in each hand. The cloth loosely swathing his loins looks like it might slip off. The audience consists of two women who are entranced by the man’s performative and exhibitionistic show.

Antiquity as counterpart and inspiration

Up to around 1900, Greco-Roman sculptures had been the works of art that without comparison attracted the most attention among the art loving pubic in Europe. Knowledge about antiquity, especially Greek sculptures and Roman copies of them, was widespread, and plaster copies were given fixtures in art academies, art museums and universities.9 Zahrtmann had a classical education and was sceptical of modern French art.10 Several of his motifs reveal an interest in Greco-Roman culture, albeit portrayed in a singular way that did not conform to the canon. His painting An Etruscan (1908) [fig.8] demonstrates that the artist has profound knowledge of the Etruscan contribution to early Greco-Roman culture.

The man in the scene is surrounded by art, with a frieze on the wall, a colourful fabric on the table, and his speckled loincloth. The beautifully-decorated hammer in his hand indicates that he is the sculptor of the urn in front of him. Zahrtmann had purchased the depicted urn in Italy and was buried in it when he died in 1917.11 The historical setting is infused with life and sensuality by the nude body and the strong colours.

The legacy from ancient Greece was also regarded by many of his contemporary practitioners in the arts as an untouched origin, with profound human knowledge, and an unlimited source of inspiration and creativity. The archaic aspect of this legacy was focused in Friedrich Nietzsche’s work The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Greek tragedy is used as a metaphor for the Dionysian, the tacit element of the creative forces, what cannot really be verbalised or explained. Classical sculpture, on the other hand, symbolised the Apollonian, the creative force that enabled ideas, intentions and thoughts to assume distinct and solid form and become comprehensible. Every Apollonian cultural expression took strength and inspiration from the Dionysian, while the Dionysian force relied on the Apollonian for its comprehensible and accessible form.12 These forces were not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they needed one another. The archaic Greek culture was described by Nietzsche as more primordial than the Roman. Zahrtmann formulated this idea in his own words: “There is an unfathomably large difference between the ancient Greek and Roman [cultures], we see that these Peoples have totally different ways of thinking. Somewhat contributing to this is perhaps that we, the Nordic peoples, are more related to the Greeks.”13

Zahrtmann painted several motifs from the Greco-Roman cultural world, but Prometheus (1904) [fig.9] is perhaps the one that is most distinctly inspired by classical myths. According to Greek mythology, the Titan Prometheus created humans out of clay and also took fire from the gods and gave it to mankind. He was punished for this by being chained to a cliff, where an eagle came every night to hack out his liver, which grew back before the next night. After many years, he was set free by Heracles. Prometheus is a young, muscular man in Zahrtmann’s painting – tanned and short-haired according to the athletic male ideal around the turn of the century. With its gaping beak, spread wings and splayed talons, the eagle looks delighted at the opportunity to feast on this male body. Prometheus shields himself with his hands, but the gesture also stretches out his naked body and exposes it to the onlooker.

The Prometheus adorning the cover of the original German edition of Die Geburt der Tragödie as well as the first Swedish edition of the book (Tragedins Födelse, 1902) [fig.10] is totally different. Here, Prometheus rises from the cliff with his own might, broken chains dangle from his arms and the eagle lies dead at his feet. He has liberated himself from his punishment and thereby takes command of his own fate. Zahrtmann seems to have been more interested in the possibility of depicting a nude male body, fully accessible to viewers of the painting.

TThe idea of the body as a work of art was formulated by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy (the English title): “Man is no longer an artist, he has become a work of art […]. The noblest clay, the costliest marble, namely man, is here kneaded and cut.”14 The relationship between work of art and physical body is not entirely clear, but the perception of the body as being malleable like a sculpture and its interior being shaped accordingly is tacit in Nietzsche’s statements. The use of attributes, poses and settings from ancient Greece, preferably Hellenic art, and combining them with contemporary attributes, poses and settings, was thus a way of evoking Greek tragedy in his own era.

The motif in the painting A Victor (1915) [fig.11] could, at first glance, be interpreted as an ancient Hellenic sculpture of an athlete who has been coloured and brought to life. The laurel wreath across his right shoulder and the golden trophy in his left hand are signs of the young man’s victory. His body actually differs from the usual renditions in classical sculpture – this man has a more compact body and defined muscles. His face and hair feel more contemporary and also do not comply with Hellenic ideals. The man is gazing at a statuette of a naked man. His posture is proud, with a broad chest and straight back. The painting is drastically cropped in a way that leads the viewer’s eyes downwards, to the man’s groin. Looking at nude men as a subject in art is one theme in this painting, while both titillating and stimulating the looker’s desire.

Restraint with regard to the temptation offered by a naked man is the theme of the painting Socrates and Alcibiades (1911), where Zahrtmann again uses cropping to indicate what is hidden from us as viewers: the man’s genitals. The philosophical meanings in this scene have been interpreted by the British art historian Michael Hatt.15 Suffice it to say that the rich tradition of ancient Greece offered Zahrtmann ample opportunity to portray nude men, and that he often created pictorial solutions that make room for the Greco-Roman tradition, intellectual reflection and the viewer’s appreciation of beauty according to modern ideals of manhood.

Antiquity was both an opposite and a model in the early 1900s in Europe. The classical imagery gave some leeway to portrayals of nudity that could, after all, be interpreted as Hellenic tradition and classical erudition. Zahrtmann blends in contemporary references, fissuring the legitimate surface so that nudity appears more erotic and accessible. The same spirit infuses the painting Endymion (1913) by the Norwegian artist Henrik Sørensen, and sculptures by the Swedish artist Carl Milles, including The Wings (1908) and The Sun Singer (1917–1926). Male nudity could be perceived as a symbol of self-control, morality, vibrancy, hardness and physical unattainability, but portrayal of nude bodies were also an invitation to see physical availability, depravity, softness and lack of restraint.

The dramatic motifs of Nordic mythology

Interest in Old Norse culture was an essential ingredient of the tendencies in the arts in the Nordic region around 1900. The notion of a specific Old Norse, archaic and simplified formal idiom was cultivated in art, architecture and crafts circles.16 The Nordic was usually constructed as a contrast to a South European tradition, where the Nordic ancestors were represented as more coarse, less refined, and not particularly cultured.17 Scenes from the Old Norse pantheon were used to portray early-20th century notions of the primitivism of the Nordic peoples. Carl Larsson, for instance, painted his monumental Midwinter’s Sacrifice (1915) for the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, Axel Törneman created a fresco of Thor and the Giants (1910) at the Östra Real school in Stockholm, and Akseli Gallen–Kallela painted scenes from the Finnish national epic Kalevala, such as Lemminkäinen’s Mother (1897) and Kullervo Cursing (1899). Dramatic, violent and juicy stories were used to reflect a distancing from the Greco-Roman tradition.

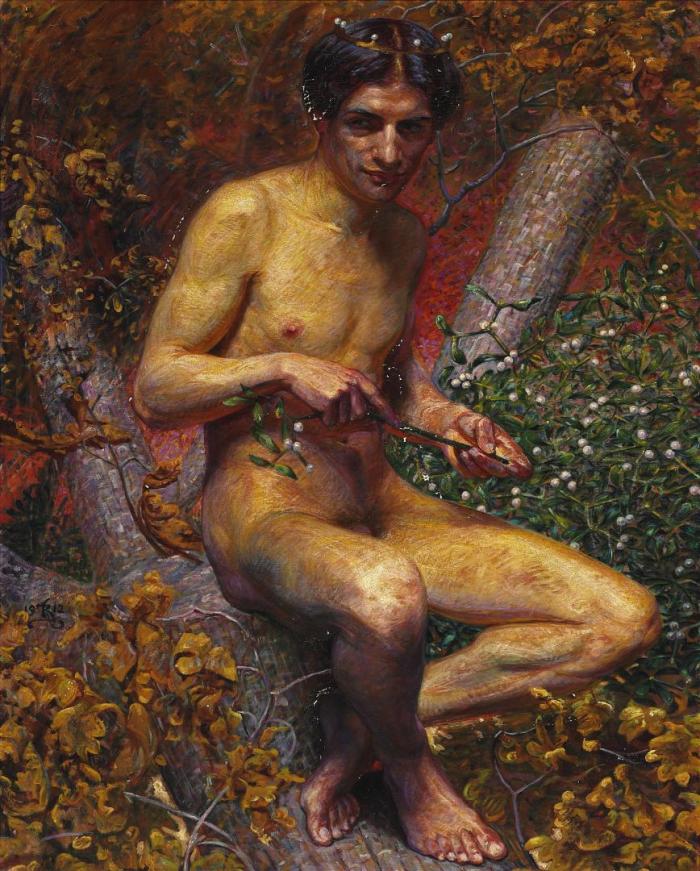

Like other Nordic artists, Kristian Zahrtmann also found material in Norse mythology, legends and history that could be illustrated with naked men. The Asa god Loki was known to be handsome but also deceitful. This duality is revealed in Zahrtmann’s Loki (1912) [fig.12], who sits in a tree picking mistletoe branches. According to the myth, Loki tricked the blind god Hoder to shoot a mistletoe arrow at his brother Balder, who was known for his kindness. Mistletoe was the only plant that could wound him. His body is slender and toned, and Loki is portrayed as a beautiful man, but his face expresses wicked thoughts. We are invited to look, at our peril – as Loki spreads his legs and lets us glimpse his sexual organ, while holding the deadly mistletoe in his hand.

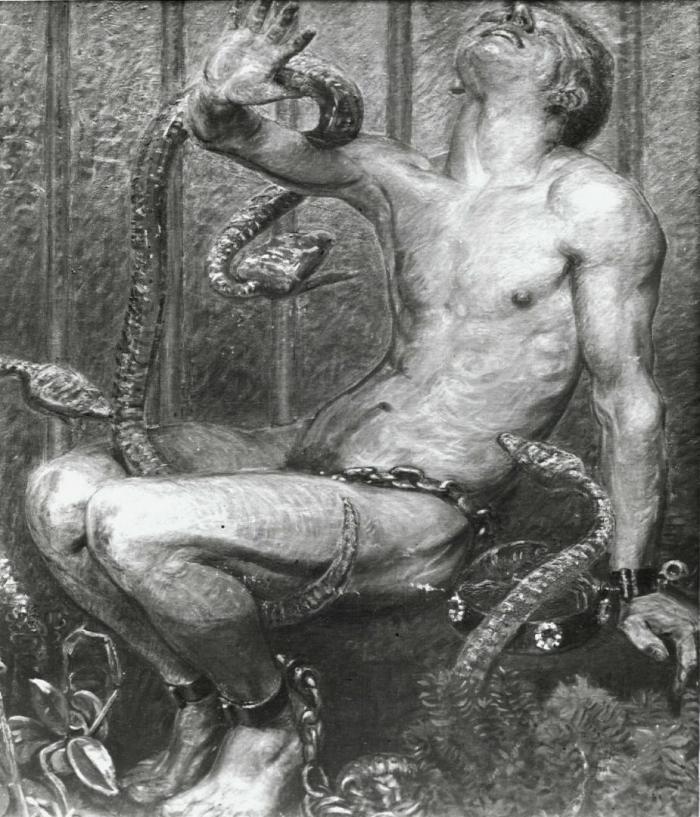

From the heroic legend of Ragnar Lodbrok, Zahrtmann culled another Norse motif: The Norse king was thrown in a snake pit for his attempt to conquer England and was bitten to death. The painting called In the Snake Pit (1915) [fig.13] shows a nude man in a cage, with snakes appearing from the greenery. His royal crown with red velvet lies next to him. According to the legend, Ragnar was an old man, but Zahrtmann paints him as an athletic youth. The snakes coil across the male body, down between his legs and towards his upper torso. Ragnar defends himself with his arms and throws back his head with an expression that could be either pain or pleasure.

Zahrtmann used the Norse tradition to portray strong feelings and forbidden fantasies about nude male bodies. Unlike many other Nordic artists who worked with the same subject matter in the Nordic countries, he seemed rather unconcerned about the bodies being typically “Nordic” compared to Mediterranean bodies, nor was he particularly interested in charging his scenes of nude, athletic men with nationalist sentiments. He does, however, use the notions of primitive Norse culture to portray men with strong erotic undertones conveying both sensual and daunting aspects.

Biblical and religious motifs – looking at bodies

The conventions of Christian tradition were being challenged from many directions around 1900, but religious motifs nevertheless filled a purpose for the artistic imagination of the new era. Even Friedrich Nietzsche, who had proclaimed that “God is dead” back in the 1880s in Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft (1882), considered parts of the Christian heritage to be acceptable. The most archaic aspects of Christianity appeared more primordial and vigorous, and were consequently inspiring.18

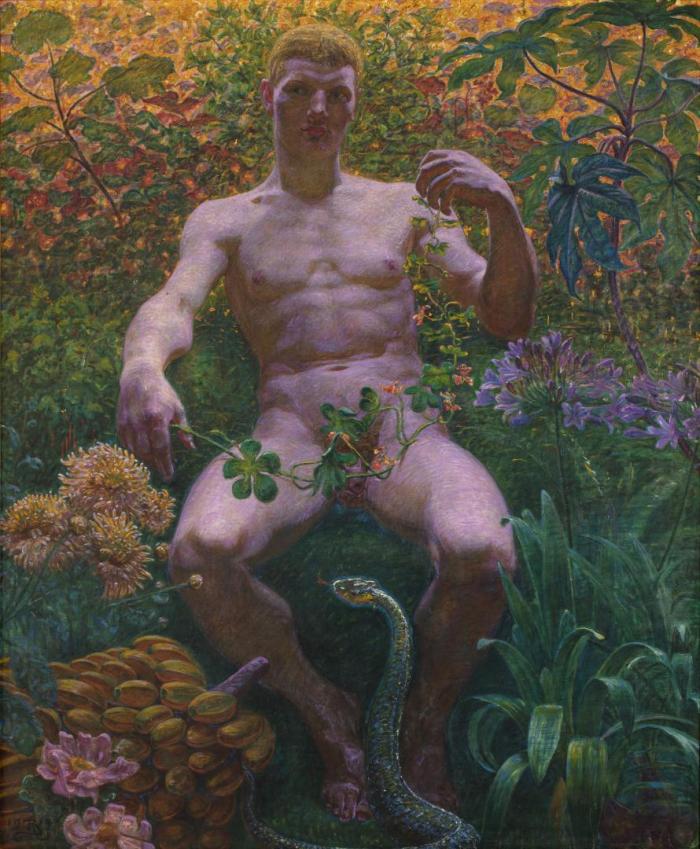

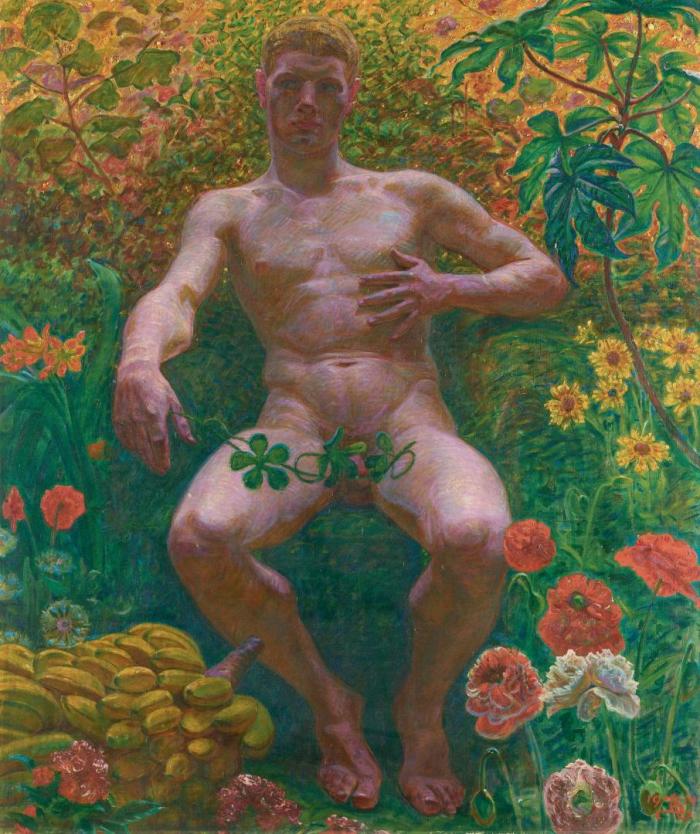

Zahrtmann’s painting Adam in Paradise (1914) [fig.14–15] is a singular take on a scene from the Old Testament. It shows Adam in a lush, verdant landscape resembling a jungle, with climbing plants, large leaves and flowers in many colours. Poppies, figs and dandelions share the space with a bountiful cluster of bananas on the ground. There are two versions of this painting, and neither features animals, apart from the snake in the first version. Adam seems unconcerned about being naked; his loins are only partially obscured by a trailing plant, and the fig leaves are still in the tree next to him, indicating that this is before the fall. The bananas can be interpreted as a visual joke, alluding to the model’s genitals, which are hidden from the viewer. Muscles and nipples are emphasised, signifying his unawareness of being naked and of any need to cover his body. The model gazes away from the viewer, but his hands draw our attention to his toned, smooth body. The hand gestures are different in the two versions, as Adam’s left hand is resting on his stomach so his thumb touches his nipple in one version. The scene refers to the biblical period preceding Eve, when Adam’s only resort for entertainment and pleasure is himself.

There was a general tendency around 1900 to historicise biblical stories in art and literature. The narratives were placed in a historical context, either in the form of historically or archeologically correct settings, or by portraying the biblical scenes with markers that are distinctly contemporary.19 Zahrtmann’s painting The Prodigal Son (1909) [fig.16] is set in a historical environment, albeit one that is not entirely consistent. The interior is luxurious and sensual, with colourful textiles, decorated picture frames and furniture, Baroque sculptures and a bowl of fruit, while Oriental costumes and classical draping suggest even older epochs. Altogether, it resembles pictures of the artist’s own studio, which, like any bourgeois parlour, featured an array of antiques, curiosities and details for effect. The prodigal son is usually portrayed wearing rags or in an emaciated state, to indicate that he has lost and wasted all his assets. Zahrtmann, instead, gives him a youthful, athletic and muscular body, in contrast to his father, who is old and draped in fabric. Despite these external differences, the touches and looks exchanged between the men indicates that the encounter is both physical and emotional and characterised by mutual affection.

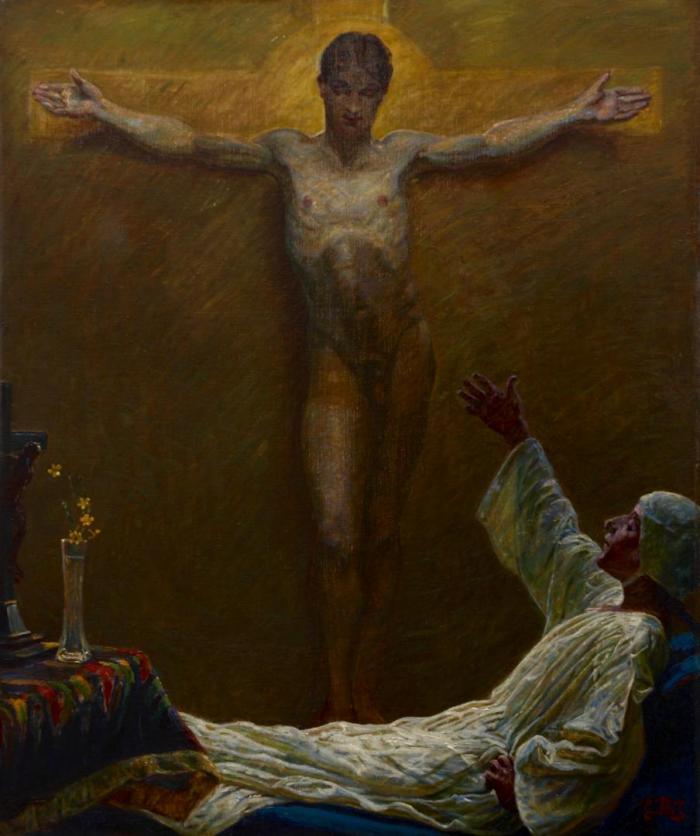

The prevailing athletic ideal was also used to give biblical characters a contemporary appearance. Jesus is usually portrayed with a gaunt body, to signify that he has taken on and incorporated the sins of humanity. Zahrtmann based his composition of the scene in Saint Catherine of Siena (1913) [fig.17] on the Dominican nun’s account of her mystic marriage to Jesus. The figure of Christ is both athletic and attractive, and the vision is shown as the unabashed fantasy of a woman who allows her physical desires to be part of her spiritual quest.

Christianity also represented an anti-rationalist emphasis on intuition, and a mystical view of emotional life in line with the spiritual quests at the time, which could challenge bourgeois moral attitudes. According to the Danish-Swedish historian of religion Edvard Lehmann, there was a newly-awakened interest in the mediaeval notion that the inner activities of the soul were linked to the outer shape of the body.20 AAdam and Eve in paradise was a subject used to portray a more carefree physicality, as in the Swedish artist Olle Hjortzberg’s frescoes in the Engelbrekt Church in Stockholm (1914), Norwegian artist Henrik Sørensen’s painting Adam and Eve (1913–1914), or Zahrtmann’s more placid take on the motif in Adam and Eve in the Garden of Paradise (1902). The fin-de-siècle ideals of beauty influenced the design of the classical subject matter, and the sensual portrayal of bodies were a legitimate way of challenging strict moral codes

Life drawing as artistic practice and personal interaction

Many artists in the late-19th century were beginning to feel that the canonical status of Greco-Roman imagery in academic art tuition, for instance, restricted their individual creativity. In 1914, the director of Sweden’s Nationalmuseum Richard Bergh put the museum’s entire collection of copies of classical sculptures in storage.21 Bergh was one of the most ardent critics of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Sweden, claiming that artists developed best if they were not steered by teachers.22 He reacted to the emphasis on Hellenic art at the expense of live models, on the past at the expense of contemporary times, and on Mediterranean culture instead of “Swedish”. “If we want to see Swedish art, we need to smash the Greco-Roman copies in our art schools, sweep up every tiny speck of debris, and air out any trace of them, purge the premises with juniper smoke and scrub the walls on which befuddled students have sketched classical draped fabrics,” he wrote.23

Zahrtmann headed a school of painting in Copenhagen in 1885–1908. Many artists from the Scandinavian countries enrolled there, and he was famous especially for his experimental approach to colour and light. But instruction was based on life drawing from real male models.24 Students were taught to observe the model, to intently study the colours and find distinct facets, which could then be combined on the canvas. Lighting was crucial, and the preserved sketches by Zahrtmann’s students show a clear difference between the models who posed in daylight and lamplight respectively. Preserved life drawing show how students such as the Swede Anders Trulson, the Danes Peter Hansen, Gunnar Sadolin, Johannes Larsen and Poul S. Christiansen, Norwegian Thorvald Erichsen and Oluf Wold-Tone, have practised turning the male body into a surface for the play of colour and light.

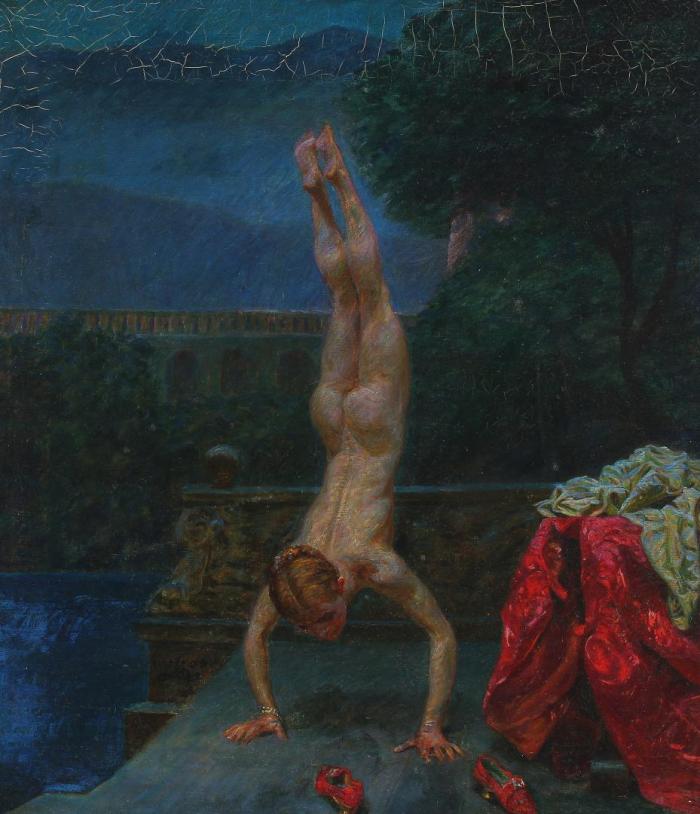

Women artists were not welcome at Zahrtmann’s school; he believed that women were incapable of becoming successful artists.25 It also became widely known that he was not keen on female models. In spring 1907, Zahrtmann’s Susanna at Her Bath (1907) [fig.18] was exhibited at Den Frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition) in Copenhagen. The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter reported:

What is remarkable about this variation on an old theme, however, is that the artist depicts Suzanna after her bath practising walking on her hands down a marble staircase. Moreover, as Zahrtmann abhors female models, Suzanna, like his previous women figures, is painted after a male model.26

On the other hand, he became very close with some of his male models. Hjalmar Sørensen, who modelled for Alcibiades, travelled with Zahrtmann to Italy in 1911. Sørensen had been embroiled in a scandal with a homosexual policeman a few years previously. Zahrtmann met the model who posed for Adam in the soldiers’ carriage on a train. In a letter, Zahrtmann writes: “I long for his arrival tomorrow, when I will enjoy him as if I were in Paradise […]”27 These stories adhere in detail to the patterns for how gay men made contact around 1900, indicating that Zahrtmann combined his personal passions with his artistic practice.

Nordic Vitalism and the artistic attraction of the male body

Other Nordic artists were also fascinated by male nudes in the early 1900s. Swimming and exercising men became a symbol of health and vitality. “The Nordic” as an idea also had a certain influence on the development of this theme, but it is also linked to the European emergence of a male homoerotic culture, and to the philosophical movement of Vitalism. Image culture was inundated with naked men engaged in sports or outdoor bathing, which not only influenced artists’ choice of subject but also notions of creativity and the artist role.28 Friedrich Nietzsche’s writings formed the base for the Vitalist mindset and were introduced to Nordic readers in the 1880s by Danish critic and scholar Georg Brandes through lectures and publications. The concepts of the German philosopher were present in Zahrtmann’s intellectual environment, as he belonged to the circle around Brandes.29 The nude bodies, strong light and scenes with sensual undertones indicate that Zahrtmann shared some common ground with Vitalism.

Powerful outdoor life, radical social criticism, sharp colours and the dissolved imagery, however, are also distinct characteristics found in many of the artists who could be regarded as Nordic Vitalists. The Danish artist group Hellener-gruppen, formed in Refnæs by artists who had studied at Zahrtmann’s school, belonged to this movement, with several paintings of nude men by Gunnar Sadolin, Folmer Bonnén, Edvard Weie and Vilhelm Tetens. Jens Ferdinand Willumsen writes that “joy of life, health and sunlight” are the cornerstones of his practice.30 His painting Sun and Youth (1910) [fig.19], one of the most central works in Nordic Vitalism, features nude children on a beach in bright hues.

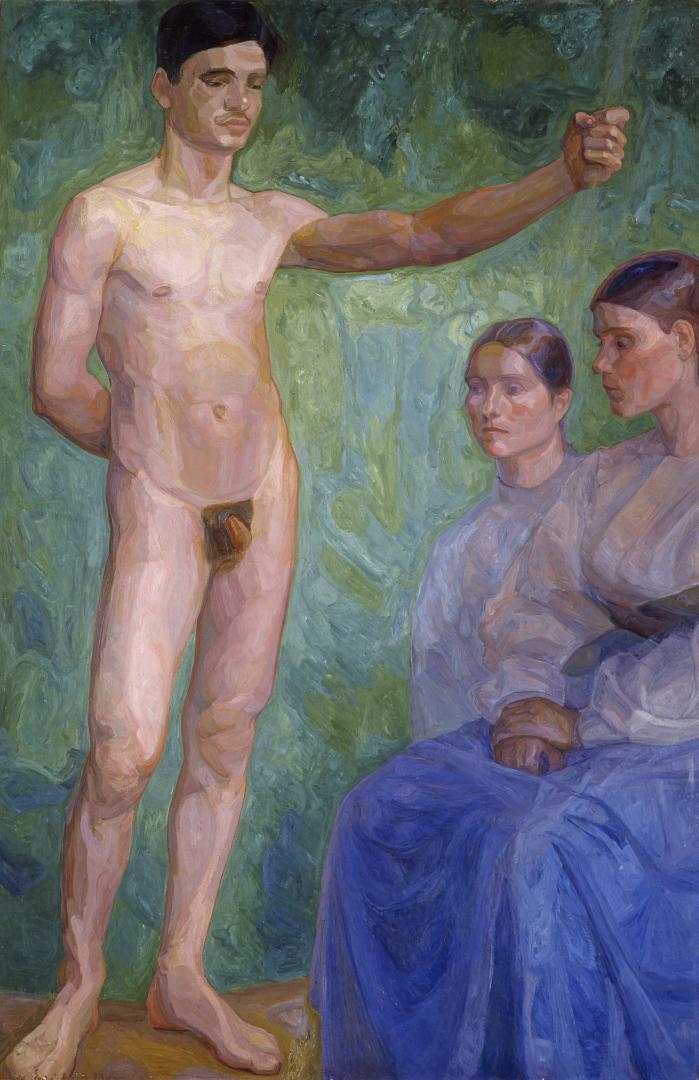

Thorvald Erichsen was one of the Norwegian students at Zahrtmann’s school. Three paintings stand out in Erichsen’s oeuvre, which mainly consists of landscapes and interiors: Yellow Boy (1903), Nude Male Nude and two Women (1903) [fig.20], and Naked People Around a God (1906). The saturated colours in these paintings was considered innovative, for instance by Henrik Sørensen.31 The distribution of roles in the scenes, with nude men posing before dressed women watching, is equally ground-breaking, and the bright colours only make the male bodies seem alluring and attractive, and charged with creative energy.

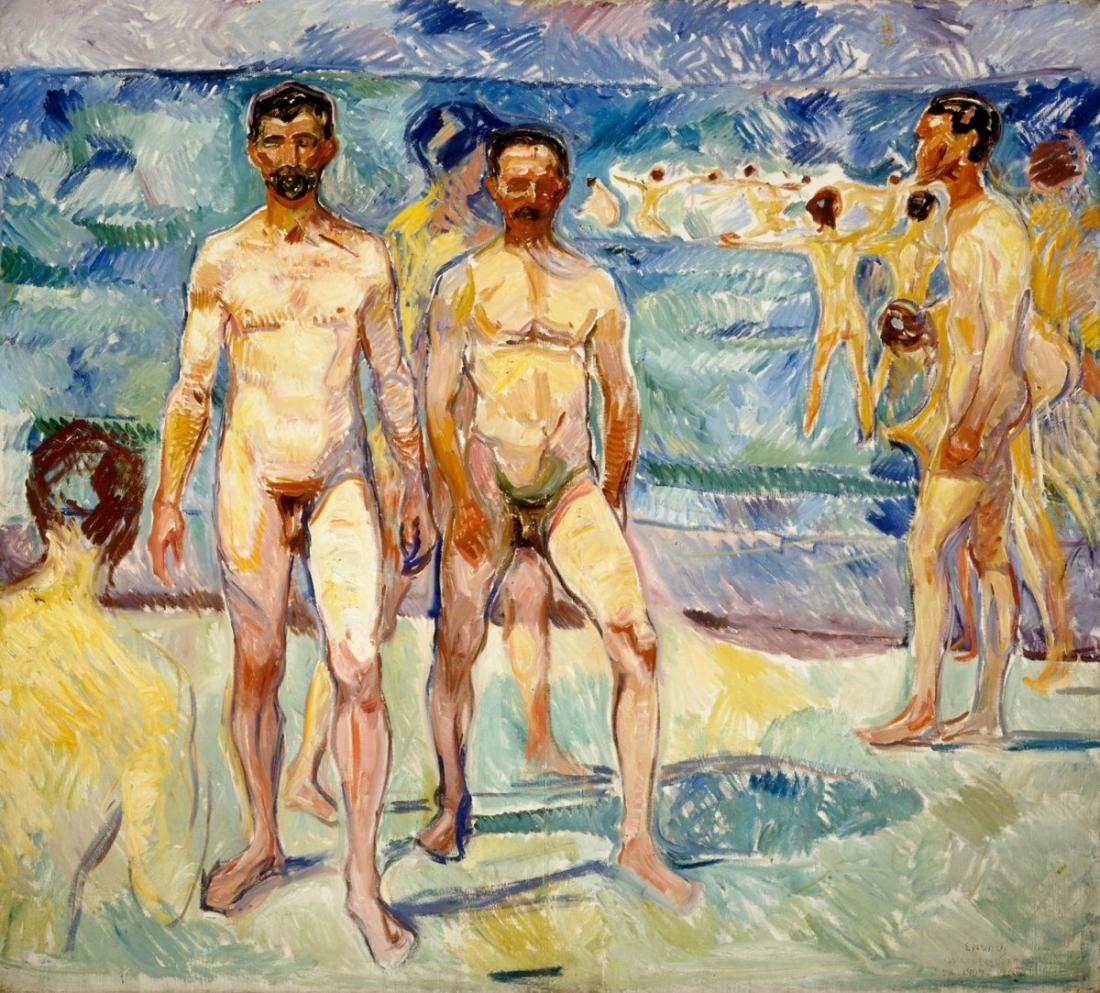

Edvard Munch’s paintings with nude men have details such as moustaches, pubic hair and swimsuit tan lines. Interpretations often have a distinctly biographical nature; for instance, it has been claimed that scenes such as Bathing Men (1907) [fig.21] were Munch’s reaction against his previous melancholic attitude to life.32 The American art historian Patricia G. Berman suggests that the reform movement’s ideas on the need for a direct link between man and nature was confirmed by the motif of the nude male.33 These motifs coincide, moreover, with the new male ideal launched in bathing culture and athletics.

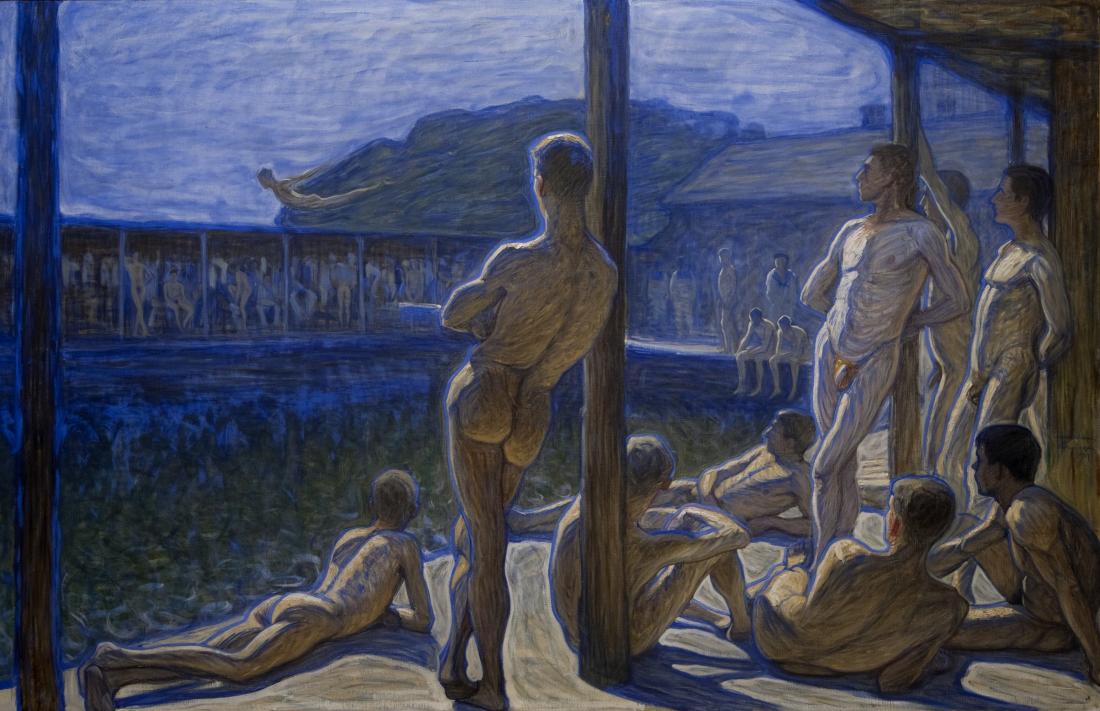

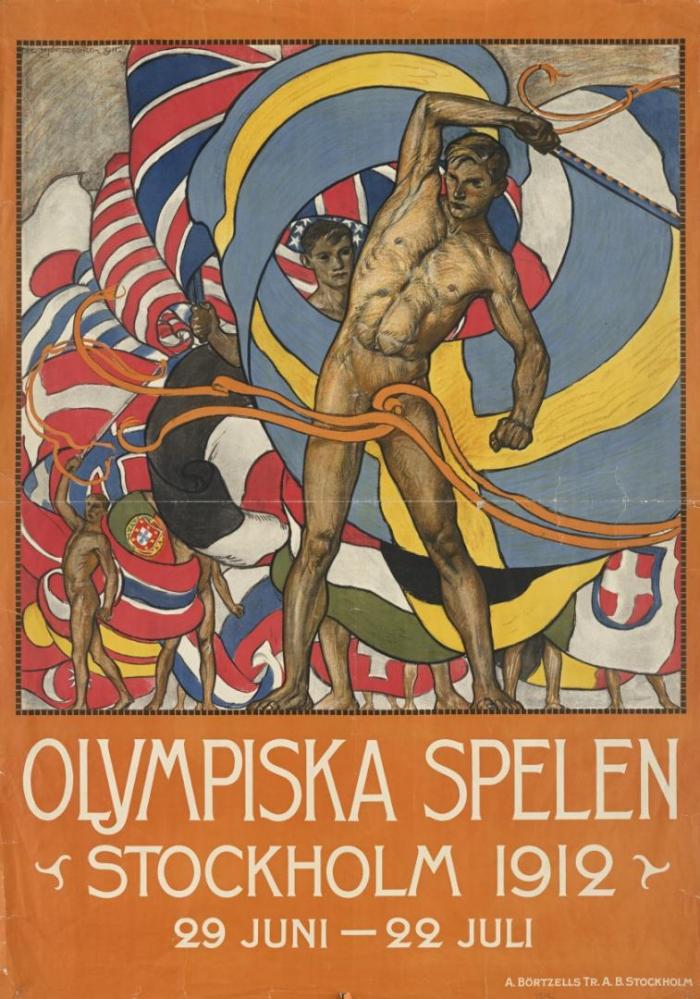

In Sweden, Eugène Jansson created his monumental, highly-pigmented paintings of men in the cold swimming baths; J.A.G. Acke painted nude men in the bleak archipelago with a rich palette. Olle Hjortzberg’s poster for the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912, featuring nude youths waving the flags of all participating nations is yet another example of naked men in art from this period [fig.22]. Nudity was an essential component in these compositions, conveying a panoply of notions relating to masculinity, nature and primordiality. The Navy Bathhouse (1907) [fig.23] by Jansson blends the emerging homosexual culture, the homoerotic potential and the voyeuristic pleasure of male, athletic bodies in all-male environments, with the Vitalist male cult.34

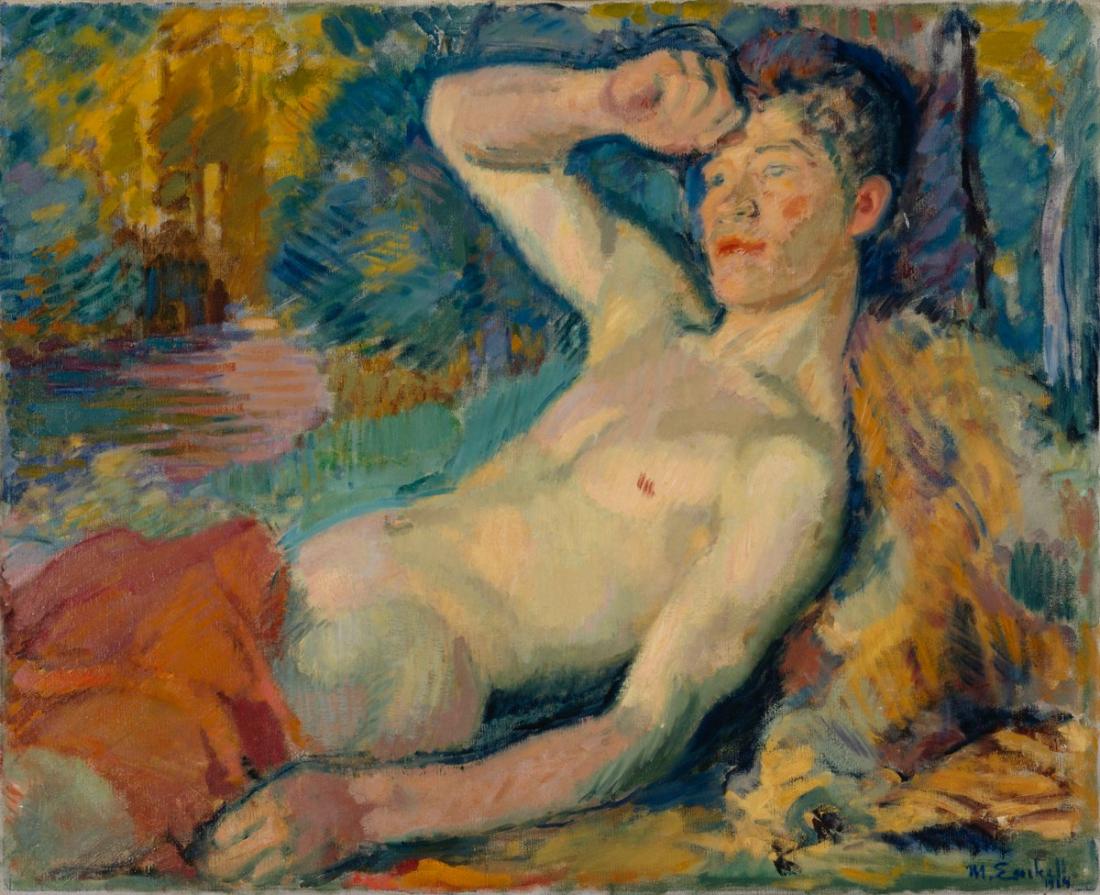

The Finnish artist Magnus Enckell often used mythological scenes as a pretext for painting nude men. Some of his motifs are overtly homoerotic, even if interpretations of his paintings have traditionally ignored the sexual aspects [fig.24].35 The Finnish artist group Septem included Verner Thomé, who, in 1910-11, painted a whole series of bathing boys – bodies, water, cliffs, beach and sunlight, each element is rendered in the same bright palette of purple, pale blue, pink, yellow, and an abundance of white.36 Children’s games could also embody the idea of a life beyond bourgeois morality.

The Nordic artists painted nude men or youths for a variety of reasons, but they all convene in the notion of the male body as being invested with a special capacity to stimulate creativity and vitality. Feelings could be friendly and professional, but also homoerotic. The desire for nude men coincides not only with public discussions claiming that the industrialisation and urbanisation of the west led to a degeneration of the population. It was also parallel with the emergence of a homosexual culture, and on the European art scene sexual liberation was seen as a facet of artistic practice belonging to avant-garde circles. Paintings of nude men could be perceived as a criticism against bourgeois morality, and notions that the Nordic tradition was more liberal and less refined than its south European counterpart may have added to making naked men a particularly common motif among these artists.

When Kristian Zahrtmann painted his most extravagant scenes with nude men in the early 1900s, he built upon the portrayal of naked male bodies in several genres around the turn of the century. Traditions from antiquity and Norse mythology and subjects from the Bible were intertwined with the artist’s striving to create new artistic traditions. Vitalism characteristically features everyday situations, more fluent brushwork and less pronounced references to literary sources than generally found in Zahrtmann’s works. But he shares the sensual and monumental style of presenting the athletic male ideal with artists such as Jansson, Enckell, Munch and others. The naked male body was given a legitimate context with references to tradition, while elements from contemporary culture were added to the composition. Even in his more conventional genre scenes, Zahrtmann had the ability to incorporate the contemporary complex relationship to nude male bodies in his paintings.