Summary

How may we understand and describe the connection existing between images that, together, form a series? This article explores the image series as a specific category, proposing that the distinctive spatial and temporal structuring principles of the series may be explained by the concept of topology, which describes an expanded geometry as well as a theory of place. The example used is Wassily Kandinsky’s (1866–1944) portfolio Small Worlds [Kleine Welten] (1922), a set of prints which very strongly and overtly addresses the relationship between the individual, singular image and the composite series.

Articles

Working in series is not unusual within the visual arts, particularly within the field of art on paper, perhaps because the relatively inexpensive material invites artists to explore a given theme, formal aspect, or perceptual and affective matter in not just a single image, but in several variants. This gives rise to the kind of series familiar from Western art history, for example in the work of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Max Klinger (1857–1920) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), to mention but a few of the many artists who have not only worked with a single image as a complete, fully finished entity in itself, a singular piece, but also with groupings comprising several images. For the purposes of this article, my empirical starting point for an art theoretical, by which I mean ontological and hermeneutical, examination of the principles ordering series of images will be Wassily Kandinsky’s (1866–1944) series of prints Small Worlds [Kleine Welten], published as a portfolio in 1922 by the Propyläen Verlag in Berlin, which commissioned the work.1 A copy of the portfolio is housed in Copenhagen in the Royal Collection of Graphic Art at the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK). Small Worlds is an interesting example when studying series as such because it sees Kandinsky overtly addressing a tension that is, I contend, inherent in any image series: a tension or perhaps even a difference between the individual image’s self-contained singularity and its simultaneous participation in the collective, the defined and composite group formed by the series.

Even at this early stage I have pointed towards how an image series must possess certain characteristics in order to merit the designation ‘series’. To be able to speak of images as variants, a kinship must exist between the individual images; they must have something in common so that they do indeed form a group, a series. Whenever we are dealing with several image-objects, a spatial relationship between them will automatically arise. They must be positioned in relation to each other in space, which in turn means that our encounter with each individual image must take place over time, either one by one or several at a time if the viewing angle allows. Roughly speaking, the image series incorporates something synchronous by virtue of the individual images and something diachronous by virtue of it being a series. In this article I will introduce the concept of topology, which describes an expanded geometry as well as a theory of place, as one possible approach to explaining the distinctive spatial and temporal nature of the image series, its structuring principles. And in the case of Small Worlds, this topology supports art’s symbolic and imaginary formation of place, its place-making, something that pertains to a utopian as well as a philosophical/existential space, specifically towards a cosmology. As a study of how images are structured and organised, focusing on formal as well as semantic links in images with particular emphasis on spatial and temporal perspectives, I hope that this article can not only contribute new perspectives on the image series as a category of images, but that it can also contribute to the development of an art theory that describes links between the formation of images, the structuring of images, space and time while considering the connections between these entities as a matter of topology.

Small Worlds

The publication of Small Worlds took place six months after Kandinsky had taken up a position as a teacher at the Bauhaus school in Weimar and as head of the mural workshop there. The series comprises twelve prints, which fall within a system governed by the three different print-making techniques used to create them: lithography, woodcut and etching (drypoint). This is to say that the series is ordered by a system of techniques that are mutually different from each other, and framed by a numerical ordering in which the three techniques are each represented by four prints, making up the total of twelve, a thinly veiled reference to other systems of cosmological ordering done in accordance with this symbolically charged number: hours, months etc. Thus, the twelve small worlds become parts of a greater totality.

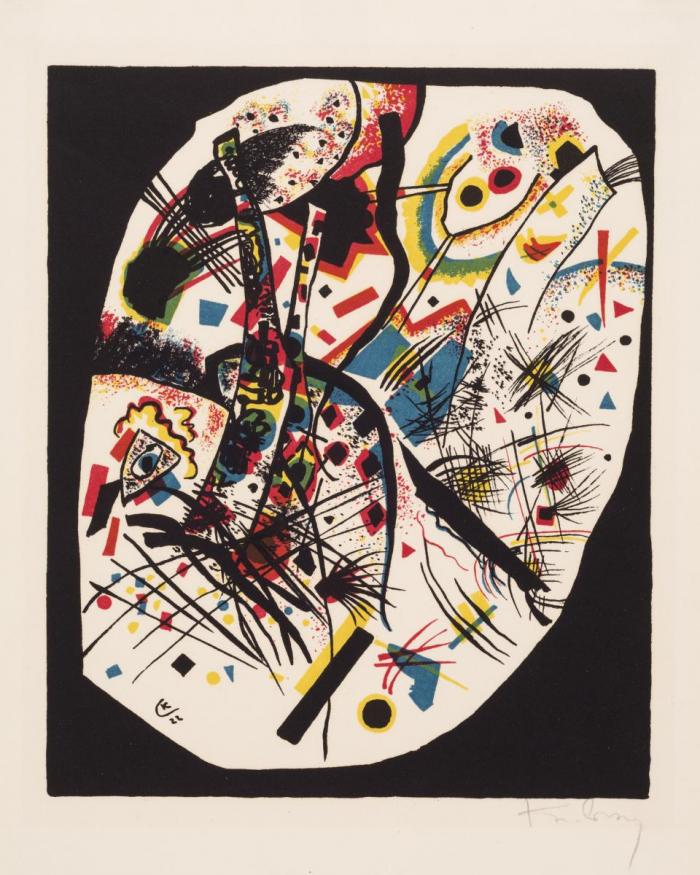

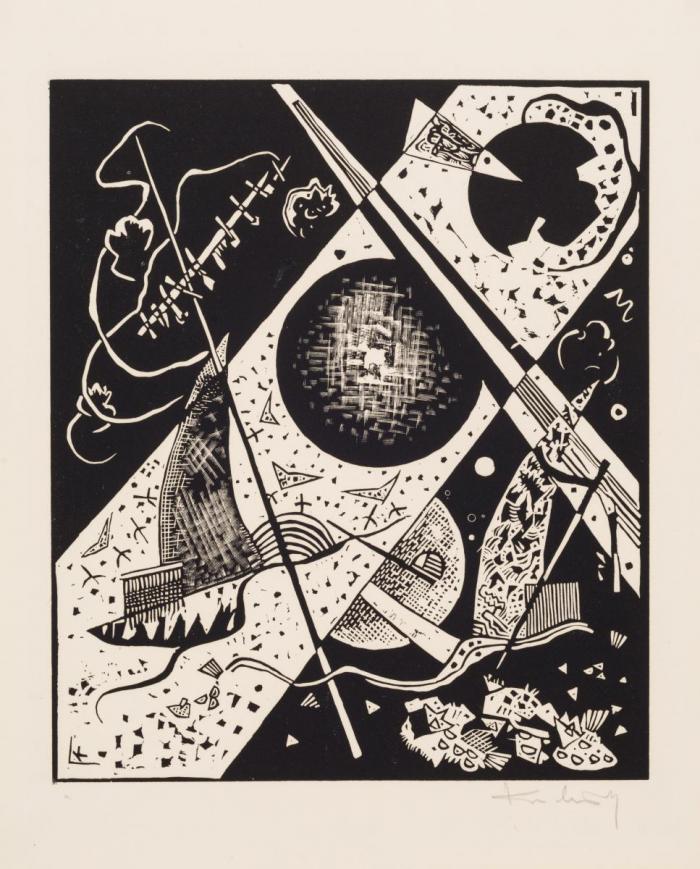

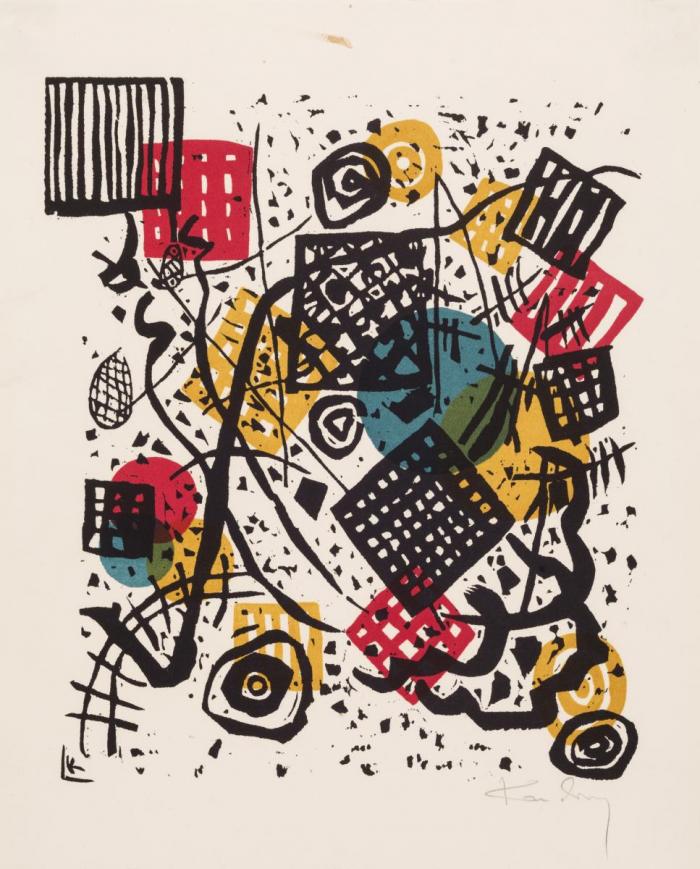

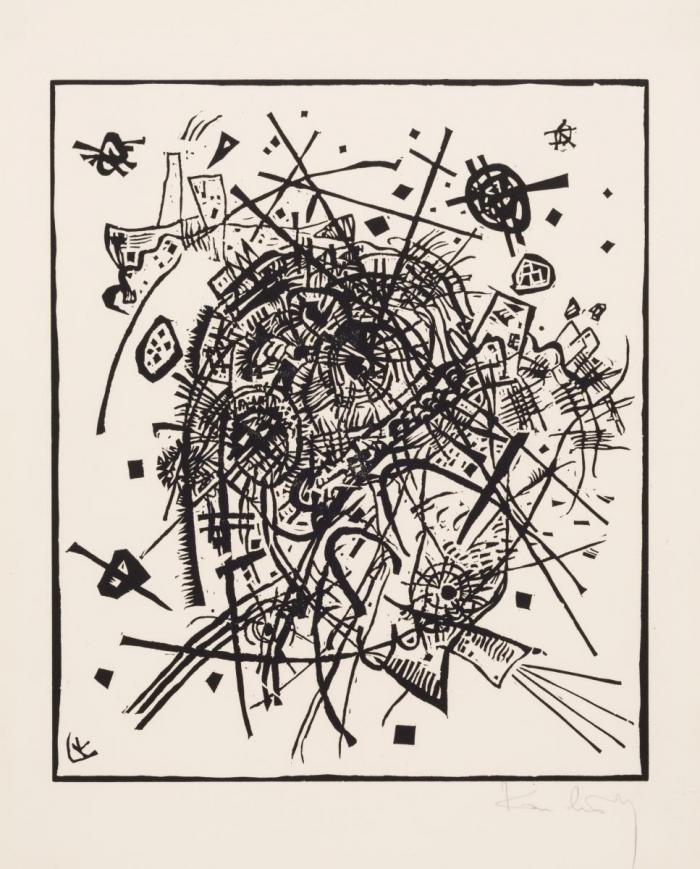

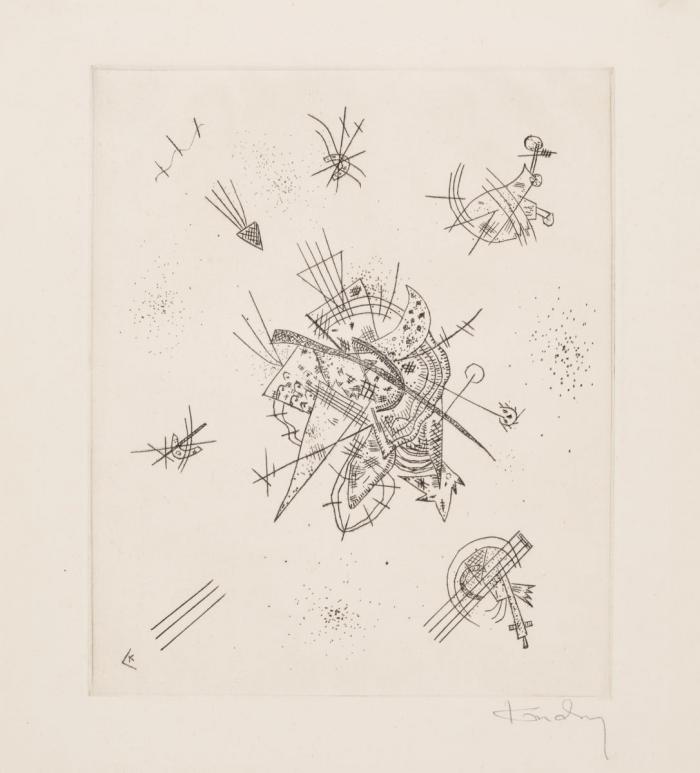

Small Worlds are abstract compositions, six of them polychrome, six monochrome, consisting of a range of different pictorial elements – sometimes geometric, sometimes amorphous. Some of the compositions appear to feature recognisable motifs, such as boat-like objects (sheets II and VI) or landscape elements (sheets I and II), while others have the diagrammatic appearance of maps in their combination of points, lines and planes (sheets VI and IX). Circles, or fragmented or approximate circles, feature in several of the prints (sheets III and IV), thereby accentuating the cosmological aspect – these are depictions of worlds. Diagonal lines are also much in evidence, adding visual tension and dynamism (sheets I, II, IV, VI, IX and XI) where centrifugal and centripetal energies seem to challenge one another. In a description of this series, Jan Würtz Frandsen has emphasised this play of forces, stating that ‘Kandinsky’s abstraction is the result of a process wherein the representational figures of his early paintings gradually become reduced to purely pictorial or iconic elements’, and also pointing towards their ‘pictorial energetics, generated by counter-movements’.2

Kandinsky articulates the actual picture plane, the graphic ground from which the figurations emerge, in various ways. Particularly in the last part of the series (sheets X–XII), the figures seem to move freely across the plane, which can either be read as something deeper, located behind the figures, or as something occupying the same level as the figures; it is immanent in the paper itself. In other cases Kandinsky marks out the image as something definitely delimited (sheets II and VI–VII), where a black ground nestles around, alongside and behind the central elements, and in sheet VIII he has a black line frame the inferno of intertwining pictorial elements that whirl around the centre of the image.

An image can in itself be described as a microcosm, as its own little world acting through its own ordering principles, including its composition. Thus, we may describe Small Worlds as consisting of individual images that nevertheless have a formal kinship with each other – and in a sense a thematic one too insofar as we see them as abstractions on the same theme: cosmology. As in music, we find variations on a theme here, all of them different from the others: some seem more energetic than the rest, others have a deeper, even darker note (sheet VII), while yet others seem lyrical, almost playful (sheet XI).

It is worth noting that Kandinsky’s view of art links up the spatial and the symphonic, meaning the harmonious combination of voices, in the 1913 text Reminiscences, where he uses musical metaphors and cosmic elements such as the sun and stars to describe Moscow while also pronouncing the city to be a kind of symphony.3 He furthermore links the overall impression of the city to viewing a work by Claude Monet (1840–1926) from the latter’s series of haystacks – a well-known example of repeated imagery, although it is not the series as such, but an individual image that appears so incomprehensible, yet fascinating to Kandinsky, particularly because the actual subject matter seems to be absent:

And suddenly, for the first time, I saw a picture. That is was a haystack, the catalogue informed me. I didn’t recognize it. I found this nonrecognition painful, and thought that the painter had no right to paint too indistinctly. I had a dull feeling that the object was lacking in this picture. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me, but impressed itself ineradicably upon my memory, always hovering quite unexpectedly before my eyes, down to the last detail. […] I had the overall impression that a tiny fragment of my fairy-tale Moscow already existed on canvas.4

This incipient abstraction, this absent subject, presents us with the question of what the picture did then, and whether it can then be said to be in harmony with other pictures in the series.

Series of images

Whereas the so-called ‘pictorial turn’ has made a considerable contribution to our understanding of the image’s ontology, hermeneutics, agency and epistemology – mainly while focusing on individual image-objects – we find that systematic studies that support an understanding of images as more than just individual phenomena and objects, but also as something that can form part of groups and even series, are rather fewer and far between.5 Art history literature repeatedly presents us with isolated, autonomous image-objects, the individual masterpiece. Many have pointed out how separating out the image-object for individual attention is in itself an artificial move – many pictures were originally envisioned as part of a wider context, posited within particular rooms or practices or in relation to other pictures. Images may be thematically linked in groups based on repetitions from one image to the next, on narratives evoked in the image, or on particular themes and modes of expression that are being explored in similar ways. We also know of countless practices where pictures form part of more or less temporary groupings, for example in exhibitions, in lectures, in photo albums, on websites and on web-based services such as Instagram and Pinterest.

Repetitions in themselves have often been thematised in art, with examples being particularly widespread since the 1960s, especially in Pop art and minimalist art. These cases involve an exploration of the serial in the sense of a process where repetition and reproduction are central aspects. The serial as artistic strategy was described back in 1967 by artist Mel Bochner in the article ‘The Serial Attitude’6 and can to some extent be linked to a more general interest in the formation of structures, as has also been studied in semiotics and in thinking founded on structuralist approaches, including Michel Foucault’s study of how order is made.7 In his article, Bochner argues for the existence of a serial method that is logical and can be generative. Thus, he distinguishes between serial art, which is subject to specific logics to the extent that the production of individual image-objects may border on the mechanical, and art in series, which denotes different, but similar versions based on the same theme and mode of expression, such as Monet’s paintings of haystacks.

With his article on medieval image systems, Wolfgang Kemp laid down the foundations for subsequent studies of groups of images; what David Ganz and Felix Thürlemann call ‘the plural image’.8 In medieval image systems, the narrative link between images often plays an important part, but Kemp also demonstrates how the ordering of such images in keeping with a narrative logic is connected to depictions of a general world order and to a third order, a figure, for example the cross. Together, these three orders – narrative, cosmology and figure – form a synthesis that has theological implications, but which also acts as an autonomous image system.

The bringing together of image-objects to form new totalities, for example in private collections, in art history writing, and as an artistic strategy, has been addressed by Felix Thürlemann in his concept of the ‘hyperimage’.9 In his analysis of the panels in Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, Thürlemann describes these panels as comprising a categorial semantic web as well as a topological ordering which, together, form a syntagmatic structure, i.e. a structuring of the parts to form a group.10 According to Thürlemann, the entire Mnemosyne Atlas as well as the individual panels are, in a semiotic sense, diagrammatic structures. Thus, according to Thürlemann, Warburg’s Atlas can be regarded as a complex art historical space-time-model where spatial and temporal axes intersect.11 In his study of Picasso’s hyperimages, Thürlemann points towards similarities to the image systems of the Middle Ages while also highlighting a difference: Picasso’s arrangements – displays created according to specific temporary systems, documented through photographs – do not involve a depiction of given, finite stories, but present an open-ended ‘narrative flow’.12

As has been briefly outlined here, we find that several different types of image groups exist, ordered in different ways. The formation of such groups may, as described by Bochner, be the result of a particular methodical approach resulting in serial image groups; it can be founded on narrative, such as the medieval image systems described by Kemp; or it may be more or less contingent on the temporary combination of images as described by Thürlemann under the designation hyperimages. But what about image series such as Small Worlds, which were not produced in a serial manner, nor founded on narrative, and where the juxtaposition of the works is a prerequisite for our understanding of the total work? What principles of ordering apply here? Writing about Ellsworth Kelly’s The Mallarmé Suite (1991), a series of drawings, Nicolas de Warren states that the individual works do not act as compositions in themselves; rather, they jointly pave the way for what de Warren describes as ‘serial depth’. According to de Warren, Kelly’s works are not about the plurality of the singular, but about a singular plurality.13 By contrast, Small Worlds is equally much about the plurality of the singular and about a singular plurality: each individual work appears as a visual statement in its own right, but at the same time it is part of the group. Singularity and combination are connected. By pointing towards the presence of a special depth, de Warren suggests that the series as such encompasses something spatial, meaning something that extends through space, something relational. Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas is pieced together from images hailing from different geographical areas and different time periods. The question is whether a corresponding topological ordering – similar to the one described by Thürlemann in connection with the Mnemosyne Atlas – may be at play in image series which were envisioned as a system from the outset, such as Small Worlds? Might a single work, arranged in a group, involve a corresponding tension of axes?

Kandinsky’s cosmology

As Horst Bredekamp has pointed out, images can be regarded as actions that actively assert something in the world, meaning that they position themselves in relation to a given context.14 They may be associated with specific intentions, but also act in their own right by virtue of their structuring and the contexts they come across. In the case of image series, this becomes a question of meeting the world with a clear, if open structure. Yet even though the image series is partially open, we cannot look at it in the same way that we look at other image categories made up of separate parts. The image series is not a collage of fragments – a form closely associated with the experience of modernity as expressed in modern art, for example in Cubism or Surrealism. As Dalibor Vesely has shown, the fragment may hold a strong position within art and architecture, and the semantic and structural openness may be said to share a kinship with the hermeneutics of the fragment, but it also differs insofar as the individual, singular image-object does not refer to an absent totality the way that the fragment does.15

Gilles Deleuze states that Monet’s first waterlily repeated all those that followed with the universality of the singular as opposed to generality.16 A spatial and temporal connection between the works, transcending ideas about chronology, must assert itself, and in this sense we may speak of something situated, of a topology. Might one then also speak about a work – comprising multiple parts, a series – establishing its own topos, in the sense of establishing its own place? A place where something is reiterated, recurring, thereby constituting a kind of local general site so that the connection between these places could in itself be said to constitute a kind of motif? Topology may involve the study of the recurring topos understood as a motif. In this article I do not wish to study specific motifs, but rather the question of how something can be regarded not only as a motif, but specifically as a recurring motif. In other words, the question of what interconnects and shores up the general in the topos in a relational sense. How is the group created? What even enables us to recognise such motifs? Which affinities are necessary, what kind of kinship? If we consider the nature of a general site, a topos, one might say that our study concerns itself with this generality, with the commonality that constitutes such sites. Underpinning this, we see that this not only involves relations between repeated instances of the same motif, but also the establishment of a kind of coherence or continuum between these motifs. It follows, then, that this is also a question of boundaries: how are topoi/motifs delimited? How do we understand that something belongs precisely here and not there within this particular region? What mechanisms enter into force in establishing these correlations, these ecologies?

The topology may be concerned with the charting of specific sites, for example that of particular backdrops in front of which a given action is played out. But within visual arts, particularly modern art, narrative and action plays a smaller part, so abstraction can render all deliberations on motifs superfluous. It is true that we have a role model in Aby Warburg’s studies of pathos formulae, meaning modes of expression that recur in art throughout time and within different cultures. However, in terms of abstract art we will find that Warburg’s studies of inter-epochal connections in the Mnemosyne Atlas offer a more useful approach. Turning once again to Small Worlds, the main issue is concerned with the relationship between different image-objects, but these are not done by different artists and in different periods as in Warburg. Instead, we are dealing with a group of images, a series, in which a shared topos is created.

We are considering images that address the sundered as well as the emergent; images in various stages of development and process. Each image creates a world, but they also do so together: jointly, the twelve prints hint at a greater order. In his introduction to Small Worlds, Peter Anselm Riedl states that not only does Kandinsky mysteriously create a unity, a totality out of the twelve sheets – the same vision or sensation can also be found in each of these sheets.17 According to Riedl a special dialectic arises: ‘Geometric solidity and a corresponding natural growth, ratio and imagination – these forces that constitute the Small Worlds – make themselves felt’.18

Karen Koehler has pointed towards the connection between Small Worlds and utopian urban planning, arguing that Kandinsky was interested in mapping and charting in the 1920s.19 She refers to formal similarities between map elements such as railways and particular visual elements in Kandinsky’s works. According to Koehler, both physical and metaphysical places are present in the series – if vaguely defined, then nevertheless still using conventions from topographical depictions, particularly of ideal cities.20 She claims that ‘one can argue for a topos in Kleine Welten and conclude that the prints, in general, suggest utopian plans’.21 The problem here is that Koehler sees Kandinsky’s works as a kind of illustration of particular ideas associated with urban planning. Her pointing out certain links and connections undoubtedly has merit; her argument of there being connections between urbanistic ideas and certain visual elements in Kandinsky’s work is compelling. However, the reading becomes too strict, attributing too little significance to other atmospheric, even spiritual aspects of the works. Rather than being about the depiction of cities in a specific sense, we may say that Small Worlds – like urban plans – express particular forms of organisation, particular relations, meaning that they can be read as diagrams. For as Koehler points out, each sheet can be regarded as a small community in itself, inasmuch as all the sheets form a small community together, as a portfolio: ‘individual images that together form an integrated whole’.22

In itself, Small Worlds forms a universe of graphic techniques, as has been pointed out by Christoph Schreirer.23 He refers to how Kandinsky, in works created immediately prior to and during World War I, employs motifs such as Judgment Day and the Flood, a destruction of the old world, after which the building of new worlds becomes a theme, as articulated in Small Worlds. Schreirer has also demonstrated that this can be seen as a reflection of the artistic ambitions that Kandinsky presented in his 1911 book On the Spiritual in Art, stating that the creation of a world of art should be tantamount to creating an entire world. In this text Kandinsky also refers to music and to spatial and temporal phenomena as metaphors for that which is produced by art:

Repetition, the piling-up of the same sounds, enriches the spiritual atmosphere necessary to the maturing of one’s emotions (even the finest substance), just as the richer air of the greenhouse is a necessary condition for the ripening of various fruits.24

Whereas the metaphysical and emotionally charged held a particularly strong position in Kandinsky’s art at the outset of his career, the rational entered the picture with the Bauhaus era, which is emphasised by the logical structure of Small Worlds, as presented in Kandinsky’s introductory sheet for the portfolio, albeit still tinted by musical metaphors:

The ‘Small Worlds’ sound forth from 12 pages. // 4 of these pages were created with the aid of stone, // 4–with that of wood, // 4–with that of copper. // 4 x 3 = 12. // Three groups, three techniques. // Each technique was chosen for its appropriate character. The character of each technique played an external role in helping to create 4 different ‘Small Worlds’. // In 6 cases, the ‘Small Worlds’ contented themselves with black lines or black patches. // The remaining 6 needed the sound of other colours as well. // 6 + 6 = 12. // In all 12 cases, each of the ‘Small Worlds’ adopted, in line or patch, its own necessary language. // 12.25

As far back as On the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky develops the idea of a dual sound, of something harmonious, an idea that is further extended in the book Point and Line to Plane published in 1926, four years after the creation of Small Worlds. In this book he speaks about the relationship between point and plane, about how multiple individual parts, multiple visual elements can create dual sounds that ultimately result in the ‘sound of the sum of all these sounds’.26 The question of harmony is also a matter of the relationship between part and whole. Christopher Short has argued that the principles of such relations are more prominent in Point and Line to Plane than in On the Spiritual in Art. He describes them as ‘the quest for instances in which opposition and juxtaposition of groups of elements or concepts are united, and for the principles according to which such unifications can occur’.27 This not only involves unity as a phenomenon, but also separation, boundaries or differentiation, often simultaneously.28 Short states that ‘the boundary, as the nexus of difference, becomes also on Kandinsky’s terms the nexus of synthesis; it constitutes both difference and continuity, and allows for simultaneous diversity and unity.’29 We can describe this simultaneity between the separating and the uniting as topological.

The singular and the composite

The image series can be characterised by not involving development or evolution (unlike the cycle), being based instead on a degree of repetition within a particular non-hierarchic order so that the artist achieves a kind of continuity, a coherence.30 In this context I think of this continuity as a particular formation of space and rhythm, a topology that also connects the image series with the act of creating a cosmology, a dynamic diagram of spatial and temporal relations. Thus, Kandinsky’s Small Worlds are not simply depictions of worlds; as a series and as a unity they also constitute a study of that which creates and makes up a world, even if the image-objects of the series mutually and separately articulate a so-called iconic difference.31

Comparing parts to one another may at first glance resemble the kind of work done within traditional stylistic and/or iconographic art history. In that context, comparative analysis is a tool resting on the idea that comparison hones our understanding of differences and similarities, ‘the principle of mutual honing’, as Thürlemann has described it, which is also associated with the ‘principle of distancing’.32 Concurrently a distribution and contraction, a modulation. We must consider whether such forces might also be involved in the individual work we call a series. Christoph Heinrich has pointed out that series are characterised by regularity as well as rhythm. In this sense the series differs from the cycle or indeed from the group of works; the former involves a particular number of works arranged in a particular sequence, while the latter is far more loosely defined, for example by an overall theme.33

The rhythmic aspect plays itself out in space and time through repetitions and differences, rather like Monet’s waterlilies or haystacks. We may describe one aspect of these differences by using Gottfried Boehm’s aforementioned concept of iconic difference, even if Boehm mainly applies the concept to individual image-objects. The term iconic difference denotes the synthesis of different forces that characterise the image, but which can be united, for example by an oscillation between the motivic and the structural. Boehm points to Monet’s depictions of the cathedral in Rouen, where each image simultaneously represents the cathedral as a figure against a ground and as a far more blurred field of blotches of colour.34 The two aspects are interwoven, embedded in each other. Thus, the pictorial synthesis appears within each individual image-object, albeit as difference.

Might this iconic difference also be said to appear between images, as a common, shared topos? For example when Small Worlds features a shared motif, a kind of figure, in each image, while image-objects also combine to form an interconnected field. In this case the tension between the motivic and the structural extends across the entire group of images. Once again we must consider how the spatial and temporal aspects appearing among several works may be described – the ordering principle that connects them. Gilles Deleuze has argued that a special rhythm arises in the paintings of Francis Bacon (1909–1992), a modulation between the images. This is particularly true when the images are arranged in triptychs, meaning that they extend over a certain distance, thereby inscribing space-time in the work. According to Deleuze, Bacon’s series encompass forces of separation, mutuality and isolation, resulting in what he terms ‘fundamental rhythms’.35 Thus, spatial and temporal forces inject themselves between the image. As Deleuze says: ‘Time is no longer in the chromatism of bodies; it has become a monochromatic eternity. An immense space-time unites all things, but only by introducing between them the distances of a Sahara, the centuries of an aeon: the triptych and its separated panels’.36 In his book about the writer Marcel Proust, Deleuze writes about art as world-making and world-opening; potentials which according to Deleuze constitute the real power of art. He quotes Proust, who states that:

Only by art can we emerge from ourselves, can we know what another sees of this universe that is not the same as ours and whose landscapes would have remained as unknown as those that might be on the moon. Thanks to art, instead of seeing a single world, our own, we see it multiply, and as many original artists as there are, so many worlds will we have at our disposal, more different from each other than those that circle in the void […].37

According to Deleuze, leaning on Proust, art allows for the breaking-down of the singular; it allows us to move outside of ourselves only to see worlds different to our own. The world becomes plural; through art it becomes small worlds. Sanford Kwinter has also addressed the question about the relationship between space and time in modernity, pointing towards time as something that does not exist per se, but unfolds itself through differentiations, in individuations ‘en bloc of points-moments that are strictly inseparable from their associated milieus or their conditions of emergence’.38 Small Worlds may – according to Karen Koehlen, as explained above – be described as communities, i.e. as milieus, even though Koehlen does not develop this argument to a more general level. Here, however, we see – as did Kwinter – the image series as an entity that in itself creates and constitutes such milieus, such composite states, thereby also seeing it as a spatial and temporal system emerging. As a work of art, Small Worlds renders the world plural, but the special aspect of Kandinsky’s series is also that this process of plurality is actively thematised. Small Worlds explores the world-making aspect, the correlation between the singular and the composite, not just as metaphysics, but precisely because art per se constitutes and makes worlds. In this sense the series is a poetics, an articulation of the foundations of art.

Insofar as the image series forms spatial and temporal milieus we might say that it creates places; a topos emerges in an expanded geometry where parts become part of a continuum while including invariance and differentiation in the process. In Small Worlds we see this in the encounter between the singular work and the overall ordering principles. The individual work emerges in black and white or in colour; it consists of points, lines and planes. Some of the image accentuate the frame-like, others emphasise the centrifugal; in some the pictorial elements appear to be undergoing states of dissolution, others hint at recognisable motifs. As Kandinsky states, each world finds its language. And at the same time each work is part of several different groups: the black and white group, the coloured group, the woodcut group, etc., just as all of the works are jointly part of the group called Small Worlds, the twelve prints of the total series, a twelve-tone harmony.

Modulations take place when we include a time aspect in our consideration of the experience and understanding of the image series – from one work to the next and on the journey through the entire series. Kandinsky’s Small Worlds are adjacent works, adjacent worlds; they mutually constitute each other, yet are also delimited. They enter into relationships with each other, embedding themselves in each other, being juxtaposed in the group, in a milieu, becoming inclusive by virtue of the effects of iconic difference across the series. Concurrently with this we realise that the notion about just one single world, our own, is in itself an image; many worlds exist, many cosmologies, entire series. As Marcel Proust put it, the many worlds of art.39

Opening up the world(s)

In this article I have addressed the image series as an object of study – a group of images intended to form a unity, yet without being structured as completed sequences in the manner of image cycles or narratives. All while remaining more closely linked and coherent than temporary groupings. My focus has rested on the image series as being intentionally artistically interconnected, as exemplified by Wassily Kandinsky’s portfolio Small Worlds from 1922. The article also aimed to build on more recent results within picture theory, particularly within the study of ‘the plural image’, but has done so by engaging with an area where there is as yet little established theory: the question of the spatial and temporal aspects of the image series, understood here as the topology of the series.

The article has addressed matters of recurrence and correlation, the structuring and ordering principles that connect images to form a series. I have described these principles as topological. Through a study of the series, compared and contrasted up against Kandinsky’s own deliberations on art theory as well as various concepts from art theory and philosophy, I have sought to argue that we may understand the series as a harmony – a conflation of voices – where the parts and the totality enter into relationships of a both continuous and differential nature. In particular, the series involves a synthesis that we may describe as topological insofar as it makes and creates places. Specifically, it is founded on spatial and temporal relationships that also encompass boundaries, rhythm and conflation.

The works in Kandinsky’s picture series Small Worlds all address themes associated with the formation of space and time, particularly as regards cosmological endeavours, the act of producing imaginary images of worlds. We might speak about the works joining up to form a conceptual space, a modulating diagram of a world-making. Small Worlds allow us to perceive the world as something relational, composite, as multiple worlds. They are cosmologies, including in the Deleuzian sense insofar as art is in itself world-making and world-opening. Thus, the formation of place – place-making – is partly about specific, physical traits, about the structuring and ordering of image-objects, and partly about the imaginary and about how something, the image act, takes place by virtue of opening up the art work and the world. ▢

Translation by René Lauritsen

The top image is a detail of Wassily Kandinsky: Small Worlds VII, 1922, National Gallery of Denmark, see sheet VII